Urban Governance and Turning African Ciɵes Around: Lagos Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementtoomloialgazettenos74,Vol46,3Rddecember,1959—Partb

ORTeSe Bes Supplement to OMloial GazetteNos 74, Vol46, 3rdDecember, 1959—Part B "LIN, 252 of 1959 © ent " “FORTS ORDINANCE,1954 (No. 27 oF 1954) Nigerian Ports Authoxity (Pilotage Districts) Order,1959 -_- Gommencennent :3rd December, 1989 The N orlatt Ports Authority~ia! oxexctse:oftho powers, and authority vosied fnfeernby section 45of the Ports Ordinance, 1954, aad of every other powor in thatb pale vested in thom do hereby makethe following ordex— 1, This Order. may be cited as the Nigerian Ports Authority..(Pilotage Citation. Districts). Order, 1959, and: shall come into operation on the 3rd day of and , December, 1959, commence- _ ment. , « 2%‘There shall baa pilotage district intthe port of Lagoswithinthe limits Lagos. set outin the Firat Schedulee tothis.Order, - pe 3, Thore shall be three pilotage districts in the port of Port Harcourt Port / within the respective limits set out in the SecondScheduleto this Orders _ Harcourt. - Provided that theprovisions of this section shallnot apply tothenavigation " within Boler Creek of2 vessel which doesnot navigate seaward ofthe Bonrly : "4, There shall. he &pilotage district in the port of Calabar withinthe Calabar. : limite eet out in the Third Scheduletothis Order. - oo 5, There shall be two pildtage districts in the port of Victoria within the Victoria.’ limite set out in the Fourth Schedule to this Order, _ 6, Pilotage shall be compulsary in the whole of the pilotage district Compulsory .gitablldhod by section. 2-of this, Ordex and in pilotagedistricts Aand B pilotage. } satublished by nection 3 of this Order. ay Mela Guha Le oy oo FIRSTSCHEDULE. _ Pitorace Drarricr—-Porr. -

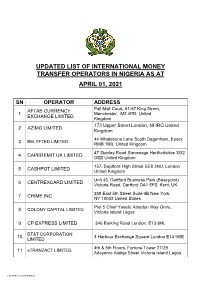

Updated List of International Money Transfer Operators in Nigeria As At

UPDATED LIST OF INTERNATIONAL MONEY TRANSFER OPERATORS IN NIGERIA AS AT APRIL 01, 2021 SN OPERATOR ADDRESS AFTAB CURRENCY Pall Mall Court, 61-67 King Street, 1 Manchester, M2 4PD, United EXCHANGE LIMITED Kingdom 173 Upper Street London, NI IRG United 2 AZIMO LIMITED Kingdom 44 Whalebone Lane South Dagenham, Essex 3 BELYFTED LIMITED RMB 1BB, United Kingdom 47 Stanley Road Stevenage Hertfordshire SG2 4 CAPEREMIT UK LIMITED OEE United Kingdom 157, Deptford High Street SE8 3NU, London 5 CASHPOT LIMITED United Kingdom Unit 46, Dartford Business Park (Basepoint) 6 CENTREXCARD LIMITED Victoria Road, Dartford DA1 5FS, Kent, UK 239 East 5th Street Suite 4B New York, 7 CHIME INC. NY 10003 United States Plot 5 Chief Yesefu Abiodun Way Oniru, 8 COLONY CAPITAL LIMITED Victoria Island Lagos 9 CP EXPRESS LIMITED 346 Barking Road London, E13 8HL DT&T CORPORATION 10 3 Harbour Exchange Square London E14 9GE LIMITED 4th & 5th Floors, Fortune Tower 27/29 11 eTRANZACT LIMITED Adeyemo Alakija Street Victoria Island Lagos Classified as Confidential FIEM GROUP LLC DBA 1327, Empire Central Drive St. 110-6 Dallas 12 PING EXPRESS Texas 6492 Landover Road Suite A1 Landover 13 FIRST APPLE INC. MD20785 Cheverly, USA FLUTTERWAVE 14 TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS 8 Providence Street, Lekki Phase 1 Lagos LIMITED FORTIFIED FRONTS LIMITED 15 in Partnership with e-2-e PAY #15 Glover Road Ikoyi, Lagos LIMITED FUNDS & ELECTRONIC 16 No. 15, Cameron Road, Ikoyi, Lagos TRANSFER SOLUTION FUNTECH GLOBAL Clarendon House 125 Shenley Road 17 COMMUNICATIONS Borehamwood Heartshire WD6 1AG United LIMITED Kingdom GLOBAL CURRENCY 1280 Ashton Old Road Manchester, M11 1JJ 18 TRAVEL & TOURS LIMITED United Kingdom Rue des Colonies 56, 6th Floor-B1000 Brussels 19 HOMESEND S.C.R.L Belgium IDT PAYMENT SERVICES 20 520 Broad Street USA INC. -

Here Is a List of Assets Forfeited by Cecilia Ibru

HERE IS A LIST OF ASSETS FORFEITED BY CECILIA IBRU 1. Good Shepherd House, IPM Avenue , Opp Secretariat, Alausa, Ikeja, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers) 2. Residential block with 19 apartments on 34, Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Dilivent International Limited). 3.20 Oyinkan Abayomi Street, Victoria Island (remainder of lease or tenancy upto 2017). 4. 57 Bourdillon Road , Ikoyi. 5. 5A George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited), 6. 5B George Street , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 7. 4A Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 8. 4B Iru Close, Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 9. 16 Glover Road , Ikoyi (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 10. 35 Cooper Road , Ikoyi, (registered in the name of Michaelangelo Properties Limited). 11. Property situated at 3 Okotie-Eboh, SW Ikoyi. 12. 35B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi. 13. 38A Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Meeky Enterprises Limited). 14. 38B Isale Eko Avenue , Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi (registered in the name of Aleksander Stankov). 15. Multiple storey multiple user block of flats under construction 1st Avenue , Banana Island , Ikoyi, Lagos , (with beneficial interest therein purchased from the developer Ibalex). 16. 226, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 17. 182, Awolowo Road , Ikoyi, Lagos , (registered in the name of Ogekpo Estate Managers). 18. 12-storey Tower on one hectare of land at Ozumba Mbadiwe Water Front, Victoria Island . -

LSETF NEWSLETTER MARCH-2 Copy

MEET TEJU ABISOYE, OUR ACTING EXECUTIVE SECRETARY he Lagos State Governor, Mr. Akinwunmi Ambode has appointed Mrs. Teju Abisoye as the Acting Exec T utive Secretary (ES) of the Lagos State Employment Trust Fund (LSETF) with effect from April 1st, 2019 pend- ing confirmation by the Lagos State House of Assembly. Prior to assuming the role of Acting ES, Mrs. Abisoye was formerly the Director of Programmes and Coordination of the LSETF. Mrs. Abisoye is a lawyer with extensive experience in development finance, project planning, execution, monitoring and evaluation of humanitarian projects, government interventions and invest- ment opportunities. Prior to joining LSETF, she served as Director (Post Award Support) of YouWIN! where she was responsible for managing consultants nationwide to provide training, monitoring & evaluation for a minimum of 1,200 Awardees annually. She has also managed the affairs of a Non-Government Organization based in Lagos. THE LSETF 3-YEAR RAPID PROGRESS AND THE 90,000 JOB CREATION FEAT ince the establishment of the LSETF three years ago, it has keenly demonstrated transp arency and accountability in all its activities, principles that represent some of The S Fund’s core values. The LSETF has continued to grow in leaps and bounds, earning public support and securing partnerships with key players in the public and private sector as well as multinational corpo- rations. Recently, the LSETF presented its 3-year social impact assessment report. The impact assess- ment exercise carried out with support from Ford Foundation, measured the achievements of the Fund’s interventions, documented the lessons learnt, and made recommendations on how to enhance the Fund’s performance in the future. -

Socio-Ecological Metabolisms of Eko Atlantic City, Lagos, Nigeria: an Unjust City?

Socio-Ecological Metabolisms of Eko Atlantic City, Lagos, Nigeria: An Unjust City? Joseph Adeniran Adedeji Department of Architecture, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria Abstract My aim in this paper is to examine the socio-ecological metabolisms involved in the production processes of Eko Atlantic City (EAC) in Lagos, Nigeria with a view to suggesting an adaptable metabolism framework based on political ecology. This is consequent upon the continually perceived ailments of this capitalist urbanisation project on the majority poor populace. Results suggest the major components of the framework to include capitalism, neoliberalism, authoritarianism, class differentiation, socio-spatial segregation, and socio-ecological disorganisation, all in the name of climate change adaptation. It concludes by advocating for strategies for framing a truly democratic and inclusive urban governance at EAC. What is the city and what forces frame its identity? Developmental mega-city projects can illuminate our understanding and guide a re-thinking of the actual meaning of the city. An evaluation of the process of recovering the ocean space to construct the 10-million square meter Eko Atlantic City (EAC) in Lagos, Nigeria, can help us redefine the city with the lenses of political ecology and social justice. The EAC is a large-scale urbanisation project that leaves a plethora of questions in inquisitive minds, especially given the project’s lopsided proceeds destined for the upper class. It has been christened a climate change adaptation project, but the larger quest borders on adaptation for whom? The discourse in the paper is structured in three parts to answer the following questions: 1) what is the socio-ecological inclusiveness of this oceanscape before the inception of EAC; 2) what are the dominant narratives in the literature on the Urban Socio-Ecological Metabolisms (USEM) that continue to trail the conception and birth of EAC; and 3) to what extent has EAC charted the course for a new urban vocabulary beyond neoliberalism to produce a new USEM framework. -

Nigeria-Singapore Relations Seven-Point Agenda Nigerian Economy Update Nigerian Economy: Attracting Investments 2008

Nigeria-Singapore Relations Seven-point Agenda Nigerian Economy Update Nigerian Economy: Attracting Investments 2008 A SPECIAL PUBLICATION BY THE HIGH COMMISSION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA IN SINGAPORE s/LAM!DSXMM PDF0- C M Y CM MY CY CMY The Brand Behind The Brands K Integrated from farm to factory gate Managing Risk at Every Stage ORIGIN CUSTOMER Farming Origination Logistics Processing Marketing Trading & Solutions Distribution & Services The Global Supply Chain Leader Olam is a We manage each activity in the supply to create value, at every level, for our leading global supply chain manager of chain from origination to processing, customers, shareholders and employees agricultural products and food ingredients. logistics, marketing and distribution. We alike. We will continue to pursue profitable Our distinctive position is based both on therefore offer an end-to-end supply chain growth because, at Olam, we believe the strength of our origination capability solution to our customers. Our complete creating value is our business. and our strong presence in the destination integration allows us to add value and markets worldwide. We operate an manage risk along the entire supply chain integrated supply chain for 16 products in from the farm gate in the origins to our 56 countries, sourcing from over 40 origins customer’s factory gate. and supplying to more than 6,500 customers U OriginÊÊÊUÊMarketing Office in over 60 destination markets. We are We are committed to supporting the suppliers to many of the world’s most community and protecting the environment Our Businesses: Cashew, Other Edible Nuts, i>Ã]Ê-iÃ>i]Ê-«ViÃÊUÊ V>]Ê vvii]Ê- i>ÕÌÃÊ prominent brands and have a reputation in every country in which we operate. -

Standard Chartered Bank Branch Network from 1St

STANDARD CHARTERED BANK BRANCH ST NETWORK FROM 1 JANUARY 2019 REGION BRANCH ADDRESS Ahmadu Bello No. 142, Ahmadu Bello Way, Victoria Island, Lagos (Head Office) Tel: +234 (1) 2368146, +234 (1) 2368154 Airport Road No. 53, Murtala Mohammed International Airport Road, Lagos Tel:234 (1) 2368686 Ajose Adeogun Plot 275, Ajose Adeogun, Victoria Island, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368051, +234 (1) 2368185 Apapa No. 40, Warehouse Road, Apapa, Lagos Tel:+234 (1) 2368752, +234 (1) 2367396 Aromire No. 30, Aromire Street, Ikeja, Lagos Tel:+234 (1) 2368830 – 1 Awolowo Road No.184, Awolowo Road, Ikoyi, Lagos LAGOS Tel:+234 (1) 2368852, +234 (1) 2368849 Broad Street No. 138/146, Broad Street, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368790, +234 (1) 2368611 Ikeja GRA No. 47, Isaac John Street, GRA Ikeja, Lagos Tel: 234 (1) 2368836 Ikota Shops K23 - 26, 41 & 42 Ikota Shopping Complex, 1/F Beside VGC, Lekki-Epe Expressway, Lagos. Tel:+234 (1) 2368841, 234 (1) 2367262 Ilupeju No. 56, Town Planning way, Ilupeju, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368845, +234 (1) 2367186 Lekki Phase 1 Plot 24b Block 94, Lekki Peninsula Scheme 1, Lekki-Epe Expressway, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368432, +234 (1) 2367294 New Leisure Mall Leisure Mall, 97/99 Adeniran Ogunsanya Street, Surulere, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) 2368827, +234 (1) 2367212 Maryland Shopping Mall 350 – 360, Ikorodu Road, Anthony, Lagos Tel: 234 (1) 2267009 Novare Mall Novare Lekki Mall, Monastery Road, Lekki-Epe Expressway, Sangotedo, Lekki-Ajah Lagos Tel: 234 (1) 2367518 Sanusi Fafunwa Plot 1681 Sanusi Fafunwa Street, Victoria Island, Lagos Tel: +234 (1) -

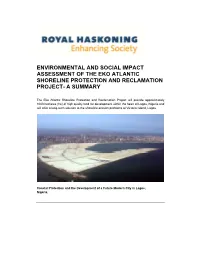

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of the Eko Atlantic Shoreline Protection and Reclamation Project- a Summary

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE EKO ATLANTIC SHORELINE PROTECTION AND RECLAMATION PROJECT- A SUMMARY The Eko Atlantic Shoreline Protection and Reclamation Project will provide approximately 1000 hectares (ha) of high quality land for development within the heart of Lagos, Nigeria and will offer a long-term solution to the shoreline erosion problems at Victoria Island, Lagos. Coastal Protection and the Development of a Future Modern City in Lagos, Nigeria. Project Location South Energyx Nigeria Ltd (SENL) was specifically created to undertake the development of the Eko Atlantic Project. Key elements of the management structure of SENL have a distinguished track record in Nigeria for the successful completion of major construction and engineering works. The Project site is located adjacent to Bar Beach, at Victoria Island, Lagos, within the Eti-Osa Local Government Area. The Need for the Eko Atlantic Project Protection: The shoreline of Victoria Island has retreated significantly over the past century. The main cause for this erosion began with the blocking of coastal sediment transport after the construction of two moles or breakwaters (between 1908 and 1912) at the entrance to the Port of Lagos. Coastal protection activity was frequently commissioned to reduce the erosion threat to Victoria Island, including several nourishment schemes. However, those attempts only temporarily mitigated the erosion and there continued to be intermittent flooding in this coastal area. The erosion culminated in 2006, when the protective beach disappeared with resultant flood damage to the road infrastructure along Bar Beach. The images presented below illustrate the situation in 2006. With no action, highly valued areas of residential and commercial property would continue to have been threatened by intrusion of sea water. -

Subnational Governance and Socio-Economic Development in a Federal Political System: a Case Study of Lagos State, Nigeria

SUBNATIONAL GOVERNANCE AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN A FEDERAL POLITICAL SYSTEM: A CASE STUDY OF LAGOS STATE, NIGERIA. SO Oloruntoba University of Lagos ABSTRACT The main objective of any responsible government is the provision of the good life to citizens. In a bid to achieve this important objective, political elites or exter- nal powers (as the case may be) have adopted various political arrangements which suit the structural, historical cultural and functional circumstances of the countries conerned. One of such political arrangements is federalism. Whereas explanatory framework connotes a political arrangement where each of the subordinate units has autonomy over their sphere of influence. Nigeria is one of three countries in Africa, whose federal arrangement has subsisted since it was first structured as such by the Littleton Constitution of 1954. Although the many years of military rule has done incalculable damage to the practice of federal- ism in the country, Nigeria remains a federal state till today. However, there are concerns over the ability of the state as presently constituted to deliver the com- mon good to the people. Such concerns are connected to the persistent high rate of poverty, unemployment and insecurity. Previous and current scholarly works on socio-economic performance of the country have been focused on the national government. This approach overlooks the possibilities that sub-na- tional governments, especially at the state level holds for socio-economic de- velopment in the country. The point of departure of this article is to fill this lacuna by examining the socio-economic development of Lagos state, especially since 1999. -

Customers Perception Approach in Nigeria

UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PRICING AS A MARKETING TOOL IN BANKS– CUSTOMERS PERCEPTION APPROACH IN NIGERIA. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POST GRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION BY MBAH, CHRIS. CHUKWUEMEKA M.SC. MBA, B.SC. 25 JULY, 2012. 1 SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS 2 CERTIFICATION This is to certify that the thesis THE EFFECTIVENESS OF PRICING AS A MARKETING TOOL IN BANKS– CUSTOMERS PERCEPTION APPROACH IN NIGERIA. Submitted to the School of Post Graduate Studies. University of Lagos For the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Is a record of the original research carried out By MBAH, CHRIS. CHUKWUEMEKA In the Department of Business Administration ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. NAME OF AUTHOR SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 1ST SUPERVISOR‟S NAME SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 2nd SUPERVISOR‟S NAME SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 1st INTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 2nd INTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. 3 EXTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………………… …………………………………. ………………….. SPGS REPRESENTATIVE SIGNATURE DATE DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my late parents who paid the initial price and laid the foundation for my education. May the Lord Almighty grant their souls eternal and blissful rest-Amen. 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writing of a university thesis, especially at Ph.D level, is very demanding in terms of time, energy and other resources of the writer and some other persons. In this vein, I am greatly indebted to numerous authors whose work were cited, read and other persons who had time to read this work at various stages, especially my supervisors: Prof. -

Seplat's Activities Impacting Nigeria's Economy, Domestic Gas Supply

JUNE 2019 VOL.2 NO.4 www.tbiafrica.com N500, $20, £10 OB3, AKK PIPELINES: ECONOMIC BARU: A TRANSFORMATIONAL PROJECTS – OILSERV BOSS TRANSFORMATIONAL 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY: WHAT HOPE FOR NIGERIANS? ACHIEVER AND REFORMIST SEPLAT’S ACTIVITIES IMPACTING NIGERIA’S ECONOMY, DOMESTIC GAS SUPPLY DRIVING 30% OF ELECTRICITY GENERATION Energy JUNE 2019 2 Energy JUNE 2019 Editor’s Note temporaries. Its operational and safety recently said the nation’s inflation rate standards align with international best increased to 11.40 per cent in May from practices, hence it wasn’t difficult for 11.37 per cent recorded in April, adding the management to take it to local and that the figure was 0.03 per cent higher international capital markets. Today, Se- than the rate recorded in April 2019. plat is the only Nigerian company fully Traffic gridlock in Lagos has become listed on both the Nigerian and London nightmarish and it gets worse by the Stock Exchanges. day as a result of heavy downpour. The Company has continued to strive Will the administration of Babajide to increase reserves and outputs from Sanwo-Olu walk the talk, or will it end its oil and gas blocks. Through its like the toothless bulldog that barks strategic implementation of redevel- without biting? opment work programme and drilling DR. NJIDEKA KELLEY In our political economy column, we campaign, the Company has been able looked at the expectations of Nigerian eplat Petroleum Development to grow production from mere 14,000 from members of the 9th National As- Company Plc has distinguished barrels of oil per day (bopd) to over sembly, highlighting the achievements itself as an outstanding and con- 84,000 bopd. -

Challenges of Housing Delivery in Metropolitan Lagos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1719 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2863 (Online) Vol.3, No.20, 2013 Challenges of Housing Delivery in Metropolitan Lagos Enisan Olugbenga, Ogundiran Adekemi (EnisanOlugbenga, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. [email protected] ) (OgundiranAdekemi, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. [email protected]) 1 ABSTRACT The need for adequate and decent housing is now part of the central focus and an integral component in National strategies for growth and poverty reduction. Decent and affordable housing is one of the basic needs of individuals, family and the community at large. As a pre-requisite to the survival of man, housing ranks second only to food. Housing as a unit of the environment has a profound influence on the health, efficient, social behaviour, satisfaction and general welfare of the community at large. It reflects the cultural, social and economic value of the society as it is the best physical and historical evidence of civilization in a country. The importance of housing in every life of human being and in national economy in general is enormous. Housing problem in Africa especially in Nigeria is not only limited to quantities but also qualities of the available housing units environment. It is in view of this that the paper views the challenges of housing delivery in the Lagos Metropolis.