Usama Bin Ladin's “Father Sheikh:” Yunus Khalis and the Return of Al-Qa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usama Bin Ladin's

Usama bin Ladin’s “Father Sheikh”: Yunus Khalis and the Return of al-Qa`ida’s Leadership to Afghanistan Harmony Program Kevin Bell USAMA BIN LADIN’S “FATHER SHEIKH:” YUNUS KHALIS AND THE RETURN OF AL‐QA`IDA’S LEADERSHIP TO AFGHANISTAN THE COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT www.ctc.usma.edu 14 May 2013 The views expressed in this paper are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, the U.S. Military Academy, the Department of Defense or the U.S. government. Author’s Acknowledgments This report would not have been possible without the generosity and assistance of the director of the Harmony Research Program at the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC), Don Rassler. Mr. Rassler provided me with the support and encouragement to pursue this project, and his enthusiasm for the material always helped to lighten my load. I should state here that the first tentative steps on this line of inquiry were made during my time as a student at the Program in Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University. If not for professor Şükrü Hanioğlu’s open‐minded approach to directing my MA thesis, it is unlikely that I would have embarked on this investigation of Yunus Khalis. Professor Michael Reynolds also deserves great credit for his patience with this project as a member of my thesis committee. I must also extend my utmost appreciation to my reviewers—Carr Center Fellow Michael Semple, professor David Edwards and Vahid Brown—whose insightful comments, I believe, have led to a substantially improved and more thoughtful product. -

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

Terrorism Versus Democracy

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:58 07 June 2016 Terrorism versus Democracy This book examines the terrorist networks that operate globally and analyses the long-term future of terrorism and terrorist-backed insurgencies. Terrorism remains a serious problem for the international community. The global picture does not indicate that the ‘war on terror’, which President George W. Bush declared in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, has been won. On the other hand it would be incorrect to assume that Al Qaeda, its affiliates and other jihadi groups have won their so-called ‘holy war’ against the Coalition against Terrorism formed after 9/11. This new edition gives more attention to the political and strategic impact of modern transnational terrorism, the need for maximum international cooperation by law-abiding states to counter not only direct threats to the safety and security of their own citizens but also to preserve international peace and security through strengthening counter-proliferation and cooperative threat reduction (CTR). This book is essential reading for undergraduate and postgraduate students of terrorism studies, political science and international relations, as well as for policy makers and journalists. Paul Wilkinson is Emeritus Professor of International Relations and Chairman of the Advisory Board of the Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence (CSTPV) at the University of St Andrews. He is author of several books on terrorism issues and was co-founder of the leading international journal, Terrorism and Political Violence. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:58 07 June 2016 Series: Political Violence Series Editors: Paul Wilkinson and David Rapoport This book series contains sober, thoughtful and authoritative academic accounts of terrorism and political violence. -

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’S Posture Toward Afghanistan Since 2001

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’s Posture toward Afghanistan since 2001 Since the terrorist at- tacks of September 11, 2001, Pakistan has pursued a seemingly incongruous course of action in Afghanistan. It has participated in the U.S. and interna- tional intervention in Afghanistan both by allying itself with the military cam- paign against the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida and by serving as the primary transit route for international military forces and matériel into Afghanistan.1 At the same time, the Pakistani security establishment has permitted much of the Afghan Taliban’s political leadership and many of its military command- ers to visit or reside in Pakistani urban centers. Why has Pakistan adopted this posture of Afghan Taliban accommodation despite its nominal participa- tion in the Afghanistan intervention and its public commitment to peace and stability in Afghanistan?2 This incongruence is all the more puzzling in light of the expansion of insurgent violence directed against Islamabad by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a coalition of militant organizations that are independent of the Afghan Taliban but that nonetheless possess social and po- litical links with Afghan cadres of the Taliban movement. With violence against Pakistan growing increasingly indiscriminate and costly, it remains un- clear why Islamabad has opted to accommodate the Afghan Taliban through- out the post-2001 period. Despite a considerable body of academic and journalistic literature on Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan since 2001, the subject of Pakistani accommodation of the Afghan Taliban remains largely unaddressed. Much of the existing literature identiªes Pakistan’s security competition with India as the exclusive or predominant driver of Pakistani policy vis-à-vis the Afghan Khalid Homayun Nadiri is a Ph.D. -

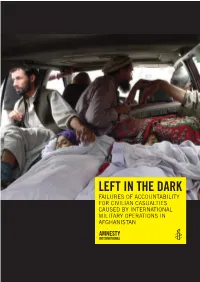

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

The Coils of the Anaconda: America's

THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN BY C2009 Lester W. Grau Submitted to the graduate degree program in Military History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date defended: April 27, 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Lester W. Grau certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE COILS OF THE ANACONDA: AMERICA’S FIRST CONVENTIONAL BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN Committee: ____________________________ Dr. Theodore A Wilson, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. James J. Willbanks, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Robert F. Baumann, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Maria Carlson, Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Jacob W. Kipp, Committee Member Date approved: April 27, 2009 ii PREFACE Generals have often been reproached with preparing for the last war instead of for the next–an easy gibe when their fellow-countrymen and their political leaders, too frequently, have prepared for no war at all. Preparation for war is an expensive, burdensome business, yet there is one important part of it that costs little–study. However changed and strange the new conditions of war may be, not only generals, but politicians and ordinary citizens, may find there is much to be learned from the past that can be applied to the future and, in their search for it, that some campaigns have more than others foreshadowed the coming pattern of modern war.1 — Field Marshall Viscount William Slim. -

Punishment Before Justice: Indefinite Detention in the US

Physicians for Human Rights Punishment Before Justice: Indefinite Detention in the US June 2011 physiciansforhumanrights.org ABOUT PHYSICIANS FOR HUMAN RIGHTS inside frontPhysicians for Human Rights (PHR) is an independent, non-profit orga- cover nization that uses medical and scientific expertise to investigate human rights violations and advocate for justice, accountability, and the health and dignity of all people. We are supported by the expertise and passion of health professionals and concerned citizens alike. Since 1986, PHR has conducted investigations in more than 40 countries around the world, including Afghanistan, Congo, Rwanda, Sudan, the United States, the former Yugoslavia, and Zimbabwe: 1988 — First to document Iraq’s use of chemical weapons against Kurds 1996 — Exhumed mass graves in the Balkans 1996 — Produced critical forensic evidence of genocide in Rwanda 1997 — Shared the Nobel Peace Prize for the International Campaign to Ban Landmines 2003 — Warned of health and human rights catastrophe prior to the invasion of Iraq 2004 — Documented and analyzed the genocide in Darfur 2005 — Detailed the story of tortured detainees in Iraq, Afghanistan and Guantánamo Bay 2010 — Presented the first evidence showing that CIA medical personnel engaged in human experimentation on prisoners in violation of the Nuremberg Code and other provisions ... 2 Arrow Street | Suite 301 Cambridge, MA 02138 USA 1 617 301 4200 1156 15th Street, NW | Suite 1001 Washington, DC 20005 USA 1 202 728 5335 physiciansforhumanrights.org ©2011, Physicians for Human Rights. All rights reserved. Front cover photo: JOSEPH EID/AFP/Getty Images ISBN:1-879707-62-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927978 Bahrain: Medical Neutrality Acknowledgments The lead author for this report is Cara M. -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct. -

The Constitutional and Political Clash Over Detainees and the Closure of Guantanamo

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH LAW REVIEW Vol. 74 ● Winter 2012 PRISONERS OF CONGRESS: THE CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL CLASH OVER DETAINEES AND THE CLOSURE OF GUANTANAMO David J.R. Frakt ISSN 0041-9915 (print) 1942-8405 (online) ● DOI 10.5195/lawreview.2012.195 http://lawreview.law.pitt.edu This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D- Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. PRISONERS OF CONGRESS: THE CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL CLASH OVER DETAINEES AND THE CLOSURE OF GUANTANAMO David J.R. Frakt Table of Contents Prologue ............................................................................................................... 181 I. Introduction ................................................................................................. 183 A. A Brief Constitutional History of Guantanamo ................................... 183 1. The Bush Years (January 2002 to January 2009) ....................... 183 2. The Obama Years (January 2009 to the Present) ........................ 192 a. 2009 ................................................................................... 192 b. 2010 to the Present ............................................................. 199 II. Legislative Restrictions and Their Impact ................................................... 205 A. Restrictions on Transfer and/or Release -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Afghanistan Ministry of Counter Narcotics

Government of Afghanistan Ministry of Counter Narcotics Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Afghanistan Opium Survey 2010 Summary Findings September 2010 ABBREVIATIONS AGE Anti-government Elements ANP Afghan National Police CNPA Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan GLE Governor-led eradication ICMP Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (UNODC) ISAF International Security Assistance Force MCN Ministry of Counter-Narcotics UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following organizations and individuals contributed to the implementation of the 2009 Afghanistan Opium Survey and to the preparation of this report: Ministry of Counter-Narcotics: Mohammad Ibrahim Azhar (Deputy Minister), Mohammad Zafar (Deputy Minister), Ahmad Haroon Shirzad (Director General), Policy &Coordination, Mir Abdullah (Deputy Director of Survey and Monitoring Directorate), Saraj Ahmad (Deputy Director of Survey and Monitoring Directorate). Survey Coordinators: Eshaq Masumi (Central Region), Abdul Mateen (Eastern Region), Abdul Latif Ehsan (Western Region), Fida Mohammad (Northern Region), Mohammed Ishaq Anderabi (North- Eastern Region), Khalil Ahmad (Southern Region), Khiali Jan Mangal (Eradication Verification Reporter), Mohammad Khyber Wardak (Database officer), Mohammad Sadiq Rizaee (Remote Sensing), Shiraz Khan Hadawe (GIS & Remote Sensing Analyst), Mohammad Ajmal (Data entry), Sahar (Data entry), Mohammad Hakim Hayat (Data entry). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (Kabul) Jean-Luc Lemahieu (Country Representative), Ashita Mittal (Deputy Representative, Programme), Devashish Dhar (International Project Coordinator), Ziauddin Zaki (National Project Coordinator), Abdul Mannan Ahmadzai (Survey Officer), Noor Mohammad Sadiq (Database Developer) Remote sensing analysts: Ahmad Jawid Ghiasee and Sayed Sadat Mehdi Eradication reporters: Ramin Sobhi and Zia Ulhaq. -

Les Talibans Et L'iskp (Daech) Dans Le District De Khogyani (Province De Nangarhar) AFGHANISTAN

AFGHANISTAN 23/11/2018 Les talibans et l’ISKP (Daech) dans le district de Khogyani (province de Nangarhar) Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par la Division de l’Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches de l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf ], se veut impartial et se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Afghanistan : Les talibans et l’ISKP (Daech) dans le district de Khogyani (province de Nangarhar) Table des matières 1. Un district majoritairement sous emprise talibane ..............................................