Abu Ubaida Al-Banshiri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al Qaeda and US Homeland Security After Bin Laden-1

CERI STRATEGY PAPERS N° 12 – Rencontre Stratégique du 10 novembre 2011 Al Qaeda and U.S. Homeland Security after Bin Laden Rick “Ozzie” NELSON The author is the Director of the Homeland Security and Counterterrorism Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, D.C. Portions of this paper relating to al Qaeda and its affiliates are drawn from The Al Qaeda and Associate Movements (AQAM) Futures Project, a collaboration between the CSIS Homeland Security and Counterterrorism Program and the CSIS Transnational Threats Project. More information on The AQAM Futures Project can be found at http://csis.org/program/future- al-qaeda-and-associated-movements-aqam. Introduction In the past year al Qaeda has suffered a series of staggering blows that have severely damaged the group and will irrevocably alter the way it operates. Last spring, Osama bin Laden was killed in a dramatic raid on his compound in Pakistan, followed by strikes on a number of other prominent al Qaeda leaders, including Anwar al-Awlaki in Yemen, Atiyah Abd al-Rahman in Pakistan, and Fazul Abdullah Mohammed in Somalia, among others1. Further, al Qaeda was caught off-guard by the “Arab Spring” revolutions that broke out across the Middle East and North Africa. These revolutions have since succeeded in toppling several regional strongmen, an avowed goal of al Qaeda that it has been unable to accomplish through terrorism. With al Qaeda’s leaders on the defensive and the efficacy of its ideology threatened by a new generation of political activists, many policymakers are increasingly questioning the future of the group2. -

Al Shabaab's American Recruits

Al Shabaab’s American Recruits Updated: February, 2015 A wave of Americans traveling to Somalia to fight with Al Shabaab, an Al Qaeda-linked terrorist group, was described by the FBI as one of the "highest priorities in anti-terrorism." Americans began traveling to Somalia to join Al Shabaab in 2007, around the time the group stepped up its insurgency against Somalia's transitional government and its Ethiopian supporters, who have since withdrawn. At least 50 U.S. citizens and permanent residents are believed to have joined or attempted to join or aid the group since that time. The number of Americans joining Al Shabaab began to decline in 2012, and by 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) replaced Al Shabaab as the terrorist group of choice for U.S. recruits. However, there continue to be new cases of Americans attempting to join or aid Al Shabaab. These Americans have received weapons training alongside recruits from other countries, including Britain, Australia, Sweden and Canada, and have used the training to fight against Ethiopian forces, African Union troops and the internationally-supported Transitional Federal Government in Somalia, according to court documents. Most of the American men training with Al Shabaab are believed to have been radicalized in the U.S., especially in Minneapolis, according to U.S. officials. The FBI alleges that these young men have been recruited by Al Shabaab both on the Internet and in person. One such recruit from Minneapolis, 22-year-old Abidsalan Hussein Ali, was one of two suicide bombers who attacked African Union troops on October 29, 2011. -

Usama Bin Ladin's

Usama bin Ladin’s “Father Sheikh”: Yunus Khalis and the Return of al-Qa`ida’s Leadership to Afghanistan Harmony Program Kevin Bell USAMA BIN LADIN’S “FATHER SHEIKH:” YUNUS KHALIS AND THE RETURN OF AL‐QA`IDA’S LEADERSHIP TO AFGHANISTAN THE COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT www.ctc.usma.edu 14 May 2013 The views expressed in this paper are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, the U.S. Military Academy, the Department of Defense or the U.S. government. Author’s Acknowledgments This report would not have been possible without the generosity and assistance of the director of the Harmony Research Program at the Combating Terrorism Center (CTC), Don Rassler. Mr. Rassler provided me with the support and encouragement to pursue this project, and his enthusiasm for the material always helped to lighten my load. I should state here that the first tentative steps on this line of inquiry were made during my time as a student at the Program in Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University. If not for professor Şükrü Hanioğlu’s open‐minded approach to directing my MA thesis, it is unlikely that I would have embarked on this investigation of Yunus Khalis. Professor Michael Reynolds also deserves great credit for his patience with this project as a member of my thesis committee. I must also extend my utmost appreciation to my reviewers—Carr Center Fellow Michael Semple, professor David Edwards and Vahid Brown—whose insightful comments, I believe, have led to a substantially improved and more thoughtful product. -

Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Paul K. Kerr Analyst in Nonproliferation Mary Beth Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation August 1, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34248 Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Summary Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal probably consists of approximately 110-130 nuclear warheads, although it could have more. Islamabad is producing fissile material, adding to related production facilities, and deploying additional nuclear weapons and new types of delivery vehicles. Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is widely regarded as designed to dissuade India from taking military action against Pakistan, but Islamabad’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal, development of new types of nuclear weapons, and adoption of a doctrine called “full spectrum deterrence” have led some observers to express concern about an increased risk of nuclear conflict between Pakistan and India, which also continues to expand its nuclear arsenal. Pakistan has in recent years taken a number of steps to increase international confidence in the security of its nuclear arsenal. Moreover, Pakistani and U.S. officials argue that, since the 2004 revelations about a procurement network run by former Pakistani nuclear official A.Q. Khan, Islamabad has taken a number of steps to improve its nuclear security and to prevent further proliferation of nuclear-related technologies and materials. A number of important initiatives, such as strengthened export control laws, improved personnel security, and international nuclear security cooperation programs, have improved Pakistan’s nuclear security. However, instability in Pakistan has called the extent and durability of these reforms into question. Some observers fear radical takeover of the Pakistani government or diversion of material or technology by personnel within Pakistan’s nuclear complex. -

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

Terrorism Versus Democracy

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:58 07 June 2016 Terrorism versus Democracy This book examines the terrorist networks that operate globally and analyses the long-term future of terrorism and terrorist-backed insurgencies. Terrorism remains a serious problem for the international community. The global picture does not indicate that the ‘war on terror’, which President George W. Bush declared in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, has been won. On the other hand it would be incorrect to assume that Al Qaeda, its affiliates and other jihadi groups have won their so-called ‘holy war’ against the Coalition against Terrorism formed after 9/11. This new edition gives more attention to the political and strategic impact of modern transnational terrorism, the need for maximum international cooperation by law-abiding states to counter not only direct threats to the safety and security of their own citizens but also to preserve international peace and security through strengthening counter-proliferation and cooperative threat reduction (CTR). This book is essential reading for undergraduate and postgraduate students of terrorism studies, political science and international relations, as well as for policy makers and journalists. Paul Wilkinson is Emeritus Professor of International Relations and Chairman of the Advisory Board of the Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence (CSTPV) at the University of St Andrews. He is author of several books on terrorism issues and was co-founder of the leading international journal, Terrorism and Political Violence. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 20:58 07 June 2016 Series: Political Violence Series Editors: Paul Wilkinson and David Rapoport This book series contains sober, thoughtful and authoritative academic accounts of terrorism and political violence. -

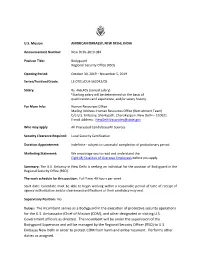

Duties: the Incumbent Serves As a Bodyguard in the Execution of Protective Security Operations for the U.S

U.S. Mission AMERICAN EMBASSY, NEW DELHI, INDIA Announcement Number: New Delhi-2019-084 Position Title: Bodyguard Regional Security Office (RSO) Opening Period: October 30, 2019 – November 5, 2019 Series/Position/Grade: LE-0701 /DLA-562042/05 Salary: Rs. 466,405 (annual salary) *Starting salary will be determined on the basis of qualifications and experience, and/or salary history. For More Info: Human Resources Office Mailing Address: Human Resources Office (Recruitment Team) C/o U.S. Embassy, Shantipath, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi – 110021. E-mail Address: [email protected] Who may apply: All Interested Candidates/All Sources Security Clearance Required: Local Security Certification Duration Appointment: Indefinite - subject to successful completion of probationary period Marketing Statement: We encourage you to read and understand the Eight (8) Qualities of Overseas Employees before you apply. Summary: The U.S. Embassy in New Delhi is seeking an individual for the position of Bodyguard in the Regional Security Office (RSO). The work schedule for this position: Full Time; 40 hours per week Start date: Candidate must be able to begin working within a reasonable period of time of receipt of agency authorization and/or clearances/certifications or their candidacy may end. Supervisory Position: No Duties: The incumbent serves as a Bodyguard in the execution of protective security operations for the U.S. Ambassador/Chief of Mission (COM), and other designated or visiting U.S. Government officials as directed. The incumbent will be under the supervision of the Bodyguard Supervisor and will be managed by the Regional Security Officer (RSO) to U.S. Embassy New Delhi in order to protect COM from harm and embarrassment. -

The Oath a Film by Laura Poitras

The Oath A film by Laura Poitras POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDe The Oath POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers New YorK , 2010 I was first interested in making a film about Guantanamo in 2003, when I was also beginning a film about the war in Iraq. I never imagined Guantanamo would still be open when I finished that film, but sadly it was — and still is today. originally, my idea for the Oath was to make a film about some - one released from Guantanamo and returning home. In May 2007, I traveled to Yemen looking to find that story and that’s when I met Abu Jandal, osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard, driving a taxicab in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. I wasn’t look - ing to make a film about Al-Qaeda, but that changed when I met Abu Jandal. Themes of betrayal, guilt, loyalty, family and absence are not typically things that come to mind when we imagine a film about Al-Qaeda and Guantanamo. Despite the dangers of telling this story, it compelled me. Born in Saudi Arabia of Yemeni parents, Abu Jandal left home in 1993 to fight jihad in Bosnia. In 1996 he recruited Salim Ham - dan to join him for jihad in Tajikistan. while traveling through Laura Poitras, filmmaker of the Oath . Afghanistan, they were recruited by osama bin Laden. Abu Jan - Photo by Khalid Al Mahdi dal became bin Laden's personal bodyguard and “emir of Hos - pitality.” Salim Hamdan became bin Laden’s driver. Abu Jandal ends up driving a taxi and Hamdan ends up at Guantanamo. -

The Iqta' System of Iraq Under the Buwayhids Tsugitaka Sato

THE IQTA' SYSTEM OF IRAQ UNDER THE BUWAYHIDS TSUGITAKA SATO* In 334 A. H. (946 A.D.), having established his authority in Baghdad, Mu'izz al-Dawla granted iqta's in the Sawad to his commanders, his asso- ciates, and his Turks. This is the formation of the so-called "military" iqta' system in the Islamic history. The appearance of the military iqta's brought about not only the evolution of the Islamic state, but also the transformation of the Iraqi society during the 10-11th centuries and of the other countries in the following periods. Nizam al-Mulk understood this as the change from bistagan (cash pay) to iqta',(1) while al-Maqrizi described as the change from 'ata' to iqta' in the same meaning.(2) As for the iqta' system under the Buwayhids, H. F. Amedroz first translated the Miskawayh's text into English with annotations,(3) and then C. H. Becker tried to realize the iqta' system in the history of 'Lehen' from the early Islamic period to the Ottoman Turks.(4) A. A, al-Duri, who studied the economic history of the Buwayhid Iraq, made clear the character of iqta' comparing it with milk (private land) and waqf, though the reality of iqta' holding remained to be investigated in future.(5) On the other hand, Cl. Cahen published the general survey of iqta' in the history of the Islamic land holding, which gave us usefull informations concerning the right and obligation of soldiers, and the fall of peasants by way of himaya (protection) and the loan at high interest.(6) We also find the general description of iqta' in the study of H. -

The Nature of Riba in Islam

THE NATURE OF RIBA IN ISLAM By: M. Umer Chapra1 Abstrak Perdebatan masalah riba seperti tidak pernah selesai di diskusikan oleh banyak kalangan, baik akademis, organisasi keagamaan, bahkan sampai pada forum-forum intenasional. Beberapa terminologi dibahas dengan baik dalam tulisan ini yang dimulai dengan pelarangan riba itu sendiri kemudian pembagian-pembagian riba, diantaranya riba al-Nasi’ah dan riba al-Fadl, serta implikasi dari dua bentuk riba tersebut. Pembahasan didukung dengan pendapat-pendapat para ulama dan ekonom yang merujuk langsung dari ayat-ayat al-Qur’an, sampai pada perdebatan hukum. Demikian juga al-Qur’an sangat jelas membedakan antara riba dan perdagangan, namun pelarangan riba sangat jelas bahkan diperkuat dengan hadits-hadits yang dengan eksplisit melarang riba. Dijelaskan pula tentang perbedaan antara riba dan bunga bank. Islam sangat menentang bunga bank karena Islam berharap terjadinya sistem ekonomi yang mengeliminasi seluruh bentuk ketidakadilan dengan memperkenalkan keadilan antara pengusaha dan pemilik modal, yaitu berbagi resiko dan berbagi hasil. ŭ ΊņĨŧ Ώ 1 ΎỲŏΉė ΞΊẂ ĤΣΔĜŧ ΔΩė ĥ ĜẃΐĨľė Έ΅ Ή ģŊΜūΕ╬ė ĥ ĜΡĜỳΉė ΎΙā ŋķā ĤΡŊĜųĨ⅝Ϋė – ĤΣẂĜΐĨį Ϋė ĤΉėŋẃΉė ŋẃħ ĥ ĜẃΐĨĴ ΐΊΉ ĤĢŧ ΕΉĜġΛ .ĤΡĜỳΉė ΖōΙ ⅜Σ⅞ĸĨΉ ĤẃĢĨ╬ė ĥ ĜΣĴ ΣħėŏĨŦΫė ∟ ĥ ĜẃΐĨľė Ίħ ╚ġ ‛ άĨŅė ŊΜį Λ ΒΏ ĤΣĴ ΣħėŏĨŦΫė Ίħ ŏŲĜΕẂ ŋķā ΞΊẂ ⅜₤ėΜħ Ĥ╤ ªΌάŦΩėΛ ĤΣΔėŏųΕΉėΛ ĤΡŊΜΚΣΉėΛ ĤΣŦΛŋΕ▀ė ŭ ŅΧė ΞΊẂΛ ªĤΣΕΡŋΉė Η╠ė ŋ⅝ ⌠ΛΧė ĤīάĬΉė ĥ ĜΔĜΡŋΉė ẀĜĢħā ΒΏ ♥ė╙Ģ΄ ♥ĜĢΔĜį ΑĜ΄ ėŌċΛ .ŊΜ⅞ΕΉė Ŵėŏ⅝ċ ΒẂ ĤΊųĸĨ╬ė ģŋĕĜ℮Ήė ┐ŏ╡ ΜΙΛ ĜΏ ΑĈġ ĤΉŊĜľė ΑΜΉΛĜ► ΝŏŅΧė ĥ ĜΔĜΡŋΉė ẀĜĢħĈġ ΠŦĈĨΉė ∟ ╚ĢỲėŏΉė ╚ΐΊŧ ╬ė -

Proquest Dissertations

The history of the conquest of Egypt, being a partial translation of Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam's "Futuh Misr" and an analysis of this translation Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hilloowala, Yasmin, 1969- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:08:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282810 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectiotiing the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons

VERSION: Charles P. Blair, “Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons,” in Gary Ackerman and Jeremy Tamsett, eds., Jihadists and Weapons of Mass Destruction: A Growing Threat (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2009), pp. 193-238. c h a p t e r 8 Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons Charles P. Blair CONTENTS Introduction 193 Improvised Nuclear Devices (INDs) 195 Fissile Materials 198 Weapons-Grade Uranium and Plutonium 199 Likely IND Construction 203 External Procurement of Intact Nuclear Weapons 204 State Acquisition of an Intact Nuclear Weapon 204 Nuclear Black Market 212 Incidents of Jihadist Interest in Nuclear Weapons and Weapons-Grade Nuclear Materials 213 Al-Qa‘ida 213 Russia’s Chechen-Led Jihadists 214 Nuclear-Related Threats and Attacks in India and Pakistan 215 Overall Likelihood of Jihadists Obtaining Nuclear Capability 215 Notes 216 Appendix: Toward a Nuclear Weapon: Principles of Nuclear Energy 232 Discovery of Radioactive Materials 232 Divisibility of the Atom 232 Atomic Nucleus 233 Discovery of Neutrons: A Pathway to the Nucleus 233 Fission 234 Chain Reactions 235 Notes 236 INTRODUCTION On December 1, 2001, CIA Director George Tenet made a hastily planned, clandestine trip to Pakistan. Tenet arrived in Islamabad deeply shaken by the news that less than three months earlier—just weeks before the attacks of September 11, 2001—al-Qa‘ida and Taliban leaders had met with two former Pakistani nuclear weapon scientists in a joint quest to acquire nuclear weapons. Captured documents the scientists abandoned as 193 AU6964.indb 193 12/16/08 5:44:39 PM 194 Charles P. Blair they fled Kabul from advancing anti-Taliban forces were evidence, in the minds of top U.S.