Applying Personality Theory to a Group of Police Bodyguards: a Physically Risky Prosocial Prototype?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Performance Police Officer in a Non-Competetive Promotion the First Day of the Payperiod Following Academy Completion

City of Bellingham Classification Specification CLASS TITLE Police Officer (Full Performance) DEPARTMENT Police UNION: POLICE GUILD SG: 29 CS: Y FLSA: Y EE04CODE: PS NATURE OF WORK: This position performs fully responsible, professional general duty police work in the protection of life and property through the enforcement of laws and ordinances. After a period of formal and on-the-job training, employees in this class are responsible for independent law enforcement duties ranging from average to considerable difficulty and performed under general supervision of a sergeant or other ranking officer. Work normally involves patrolling in an unaccompanied automobile, motorcycle, bicycle or foot patrol, and/or conducting detailed criminal investigations, traffic regulation, or community policing activities in a designated area on an assigned shift. Work involves a substantial element of danger and requires the responsible exercise of appropriate judgment in meeting critical emergency situations. Employees are sworn to act on behalf of the Police Department and the City of Bellingham and carry firearms in the performance of their duties. Employees may be directed to work on, lead, or plan special projects or assignments which call upon specialized abilities and knowledge attained through experience as a uniformed officer. Work of this class may be reviewed by superior officers via personal inspection, reviews of reports and/or oral discussion. ESSENTIAL FUNCTIONS: 1. Patrols a designated area of City on foot, bicycle, or in an automobile, motorcycle or small watercraft to investigate, deter and/or discover possible violations of criminal and vehicle (and/or boating) traffic laws, codes and/or ordinances. Maintains radio contact with the dispatch center. -

Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Paul K. Kerr Analyst in Nonproliferation Mary Beth Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation August 1, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34248 Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Summary Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal probably consists of approximately 110-130 nuclear warheads, although it could have more. Islamabad is producing fissile material, adding to related production facilities, and deploying additional nuclear weapons and new types of delivery vehicles. Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is widely regarded as designed to dissuade India from taking military action against Pakistan, but Islamabad’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal, development of new types of nuclear weapons, and adoption of a doctrine called “full spectrum deterrence” have led some observers to express concern about an increased risk of nuclear conflict between Pakistan and India, which also continues to expand its nuclear arsenal. Pakistan has in recent years taken a number of steps to increase international confidence in the security of its nuclear arsenal. Moreover, Pakistani and U.S. officials argue that, since the 2004 revelations about a procurement network run by former Pakistani nuclear official A.Q. Khan, Islamabad has taken a number of steps to improve its nuclear security and to prevent further proliferation of nuclear-related technologies and materials. A number of important initiatives, such as strengthened export control laws, improved personnel security, and international nuclear security cooperation programs, have improved Pakistan’s nuclear security. However, instability in Pakistan has called the extent and durability of these reforms into question. Some observers fear radical takeover of the Pakistani government or diversion of material or technology by personnel within Pakistan’s nuclear complex. -

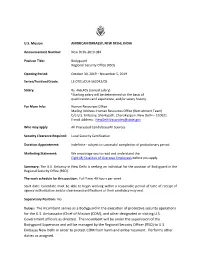

Duties: the Incumbent Serves As a Bodyguard in the Execution of Protective Security Operations for the U.S

U.S. Mission AMERICAN EMBASSY, NEW DELHI, INDIA Announcement Number: New Delhi-2019-084 Position Title: Bodyguard Regional Security Office (RSO) Opening Period: October 30, 2019 – November 5, 2019 Series/Position/Grade: LE-0701 /DLA-562042/05 Salary: Rs. 466,405 (annual salary) *Starting salary will be determined on the basis of qualifications and experience, and/or salary history. For More Info: Human Resources Office Mailing Address: Human Resources Office (Recruitment Team) C/o U.S. Embassy, Shantipath, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi – 110021. E-mail Address: [email protected] Who may apply: All Interested Candidates/All Sources Security Clearance Required: Local Security Certification Duration Appointment: Indefinite - subject to successful completion of probationary period Marketing Statement: We encourage you to read and understand the Eight (8) Qualities of Overseas Employees before you apply. Summary: The U.S. Embassy in New Delhi is seeking an individual for the position of Bodyguard in the Regional Security Office (RSO). The work schedule for this position: Full Time; 40 hours per week Start date: Candidate must be able to begin working within a reasonable period of time of receipt of agency authorization and/or clearances/certifications or their candidacy may end. Supervisory Position: No Duties: The incumbent serves as a Bodyguard in the execution of protective security operations for the U.S. Ambassador/Chief of Mission (COM), and other designated or visiting U.S. Government officials as directed. The incumbent will be under the supervision of the Bodyguard Supervisor and will be managed by the Regional Security Officer (RSO) to U.S. Embassy New Delhi in order to protect COM from harm and embarrassment. -

The Oath a Film by Laura Poitras

The Oath A film by Laura Poitras POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDe The Oath POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers New YorK , 2010 I was first interested in making a film about Guantanamo in 2003, when I was also beginning a film about the war in Iraq. I never imagined Guantanamo would still be open when I finished that film, but sadly it was — and still is today. originally, my idea for the Oath was to make a film about some - one released from Guantanamo and returning home. In May 2007, I traveled to Yemen looking to find that story and that’s when I met Abu Jandal, osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard, driving a taxicab in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. I wasn’t look - ing to make a film about Al-Qaeda, but that changed when I met Abu Jandal. Themes of betrayal, guilt, loyalty, family and absence are not typically things that come to mind when we imagine a film about Al-Qaeda and Guantanamo. Despite the dangers of telling this story, it compelled me. Born in Saudi Arabia of Yemeni parents, Abu Jandal left home in 1993 to fight jihad in Bosnia. In 1996 he recruited Salim Ham - dan to join him for jihad in Tajikistan. while traveling through Laura Poitras, filmmaker of the Oath . Afghanistan, they were recruited by osama bin Laden. Abu Jan - Photo by Khalid Al Mahdi dal became bin Laden's personal bodyguard and “emir of Hos - pitality.” Salim Hamdan became bin Laden’s driver. Abu Jandal ends up driving a taxi and Hamdan ends up at Guantanamo. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

Seattle Police Department

Seattle Police Department Adrian Diaz, Interim Chief of Police (206) 684-5577 http://www.seattle.gov/police/ Department Overview The Seattle Police Department (SPD) addresses crime, enforces laws, and enhances public safety by delivering respectful, professional, and dependable police services. SPD divides operations into five precincts. These precincts define east, west, north, south, and southwest patrol areas, with a police station in each area. The department's organizational model places neighborhood-based emergency response services at its core, allowing SPD the greatest flexibility in managing public safety. Under this model, neighborhood-based personnel in each precinct assume responsibility for public safety management, primary crime prevention and law enforcement. Precinct-based detectives investigate property crimes and crimes involving juveniles, whereas detectives in centralized units located at SPD headquarters downtown and elsewhere conduct follow-up investigations into other types of crimes. Other parts of the department function to train, equip, and provide policy guidance, human resources, communications, and technology support to those delivering direct services to the public. Interim Police Chief Adrian Diaz has committed the department to five focus areas to anchor itself throughout the on-going work around the future of community safety: • Re-envisioning Policing - Engage openly in a community-led process of designing the role the department should play in community safety • Humanization - Prioritize the sanctity -

A Brief History of U.S.-Turkey Tensions (1960-2017) in Early October, the Arrest of a Turkish Employee at the U.S

THO FACTSHEET November 22, 2017 A Brief History of U.S.-Turkey Tensions (1960-2017) In early October, the arrest of a Turkish employee at the U.S. consulate in Istanbul prompted Washington to take an unprecedented, retaliatory measure. The U.S. announced it would suspend non-immigrant services in Turkey, its NATO ally of more than sixty years. Turkey responded in kind. While the crisis has recently been partially diffused, the spat has been called the lowest point in U.S.-Turkey relations.1 Yet the two governments have had their difficulties before. As a CFR task force described in a 2012 report, “a mythology surrounds U.S.-Turkey relations, suggesting that Washington 2 and Ankara have, through six decades, worked closely and with little friction.” While the overarching relationship remains strategic and important, here are some of the notably sour moments. June of 1964 Exchange of Letters Between President Late 1960’s Johnson and Prime Minister Inonu Sixth Fleet Clashes over Cyprus Turkish anti-American sentiment grew rapidly over ACTORS these years, particularly from left-wing elements U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, Turkey’s Prime concerned with Turkey’s perceived dependence Minister (PM) Ismet Inonu on the U.S. and NATO. Protests often focused on the presence of American servicemen in Turkey, CONTEXT the privileges they enjoyed, and a general desire Ethnic tensions and violence in Cyprus (home to a for a non-aligned Turkey (“bagimsiz Turkiye”). sizeable ethnic Turkish minority) led Turkey to Mass demonstrations and violent clashes broke consider an invasion of the island. out during several U.S. -

37 Police Equipment for Police Constables

ATTORNEY GENERAL 37 POLICE EQUIPMENT FOR POLICE CONSTABLES APPOINTED BY TOWNSHIP TRUSTEES-TRUSTEES WITHOUT LEGAL AUTHORITY TO PURCHASE-SECTION 509.16 RC. SYLLABUS: Township trustees are without legal authority to buy police equipment for police constables appointed by them pursuant to the provisions of Section 509.16 of the Revised ,Code. Columbus, Ohio, February 9, 1954 Hon. William A. Ambrose, Prosecuting Attorney Mahoning County, Youngstown, Ohio Dear Sir: I have before me your letter asking my opinion as to the authority of the township trustees to purchase police equi,pment for regularly em ployed salaried police constables. The statutory provision relative to the appointment of -police constables is found in Section 509. 16 of the Revised Code, and reads as follows : "The board of township trustees may designate any qualified person as a police consta:ble. The board may pay each police con stable, from the general funds of the township, such compensation as the 1board by resolution prescribes for the time actually spent in keeping the peace, protecting ,property, and performing duties as a police constable. Such police constable shall not 'be paid fees in addition to the compensation allowed by the board for services rendered as a police constaJble. All constable fees provided for by section 509. r 5 of the Revised Code, where due for services rendered while the constable performing such services is being compensated as a police constable for his performance, shall be paid into the general fund of the township." Prior to the recent codification, this section appeared in substa..ritially the same form as Section 3348, General Code. -

2020 Annual Report MISSION in Support of the Port of Seattle’S Mission, We: • Fight Crime, • Protect and Serve Our Community

PORT OF SEATTLE POLICE 2020 Annual Report MISSION In support of the Port of Seattle’s Mission, we: • fight crime, • protect and serve our community. VISION To be the nation’s finest port police. GUIDING PRINCIPLES • Leadership • Integrity • Accountability Port of Seattle Commissioners and Executive Staff: It is my pleasure to present to you the 2020 Port of Seattle Police Department Annual Report. This past year was challenging in unprecedented ways. COVID-19 significantly impacted our day-to-day operations and our employees and their families. National civil unrest and demand for police reform led to critique and an ongoing assessment of the department. Changes in leadership, ten retirements, and a hiring freeze compounded the pressures and stress on your Police Department members. However, despite these challenges, I am proud to say that the high caliber professionals in the department stepped up. They adapted to the new environment and continued to faithfully perform their mission to fight crime, and protect and serve our community. Port employees, business partners, travelers, and visitors remained safe yet another year, because of the teamwork and outstanding dedication of the people who serve in your Police Department. As you read the pages to follow, I hope you enjoy learning more about this extraordinary team. On behalf of the exemplary men and women of this Department, it has been a pleasure to serve the Port of Seattle community. - Mike Villa, Deputy Chief Table of Contents Command Team . 6 Jurisdiction .........................................7 Community Engagement ...........................8 Honor Guard .......................................9 Operations Bureau .................................10 Port of Seattle Seaport . 11 Marine Patrol Unit .................................12 Dive Team .........................................12 SEA Airport . -

Deputy Chief of Police

The Port of Seattle Police Department is seeking a Deputy Chief of Police Salary: $129,090 - $161,362 D E P U T Y C H I E F O F P O L I C E Excellent opportunity for a talented public safety The Deputy Chief of Police must be a good professional to serve in a well-managed listener, skilled communicator, and team builder. organization and to assist in leading a 101- officer He/She will represent the department on a variety police department that takes pride in its mission, of internal and external panels and coalitions. The services provided, and contribution to quality of Deputy Chief of Police must be a proactive and life. energetic participant in these endeavors, and provide strategic input from the department’s perspective, as well as from the port’s broader CANDIDATE PROFILE perspective. The Port of Seattle Police Department is He/She must have the ability to identify and seeking a strong, decisive individual who analyze issues, prioritize tasks, and develop demonstrates a clear command presence alternative solutions, as well as evaluate balanced with well-developed interpersonal courses of action and reach logical skills. Given the unique nature of the conclusions. department, the Deputy Chief of Police must place a high premium on customer service. The Deputy Chief of Police must be a highly The successful candidate will lead by example, skilled leader and manager of people. As one of setting the tone of honest, ethical behavior, the senior leaders within the department, he or demonstrating integrity beyond reproach. she will partner with the Chief in driving change and continuous improvement. -

Pakistan | Freedom House

Pakistan | Freedom House http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2012/pakistan About Us DONATE Blog Contact Us REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Donate FREEDOM IN THE WORLD Pakistan Pakistan Freedom in the World 2012 OVERVIEW: 2012 In 2011, tensions between the civilian government, the military and SCORES intelligence agencies, and the judiciary—and attempts by all three groups to exert greater control over policy formulation—continued to STATUS threaten the government’s stability and the consolidation of democracy in Pakistan. Societal discrimination and attacks against religious Partly minorities and women, as well as weak rule of law and impunity, remained issues of concern. Journalists and human rights defenders Free came under increased threat during the year, particularly those who FREEDOM RATING spoke out on Pakistan’s blasphemy laws or abuses by security and intelligence agencies. Freedom of expression also suffered due to official 4.5 attempts to censor online media content and greater self-censorship on sensitive issues. The army’s campaigns against Islamist militants in the CIVIL LIBERTIES tribal areas led to a range of human rights abuses, displacement of civilians, and retaliatory terrorist attacks across the country, while 5 violence in Balochistan and the city of Karachi worsened. POLITICAL RIGHTS Pakistan was created as a Muslim homeland during the partition of British India 4 in 1947, and the military has directly or indirectly ruled the country for much of its independent history. As part of his effort to consolidate power, military dictator Mohammad Zia ul-Haq amended the constitution in 1985 to allow the president to dismiss elected governments. -

MARINE PATROL DETAIL Published by PCS On10/31/2019 2

Published by PCS on10/31/2019 1 STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES FIELD OPERATIONS DIVISION MARINE PATROL DETAIL Published by PCS on10/31/2019 2 MIAMI POLICE PATROL SUPPORT UNIT MARINE PATROL DETAIL STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES SUBJEC T TAB MPD BADGE COVER SHEET ENDORSEMENT SHEET MASTER INDEX INDEX LETTER OF PROMULGATION A ORGANIZATIONAL CHART OF ELEMENT B MISSION, GOALS, AND OBJECTIVES C DUTY HOURS DRESS D DUTIES AND REPONSIBILITIES OF MEMBERS E PROGRAMS, PROJECTS, OR FUNCTIONS F UNIT POLICIES G CARE AND HANDLING OF VEHICLES SOP-1 CARE, USE, AND HANDLING OF VESSELS SOP-2 GENERAL OPERATIONAL POLICIES SOP-3 - 2 - Published by PCS on10/31/2019 3 Master Index (continued) SUBJECT TAB ARREST SITUATIONS SOP-4 DEFENSIVE BOARDING PROCEDURES FOR SMALL BOATS SOP-5 GUIDELINES AND TECHNIQUES FOR TRAINING IN SOP-6 UNDERWATER RECOVERIES SPECIAL WEAPONS CARE AND USE SOP-7 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK SOP-8 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK SOP-9 HURRICANE PREPAREDNESS PLAN SOP-10 ANNEX- FIELD SUPPORT SECTION - EMERGENCY MOBILIZATION SOP 24 HOUR ON-CALL DIVERS SOP-11 CARE, USE. AND HANDLING OF SPECIAL PURPOSE SOP-12 PERSONAL WATER CRAFT AFTER HOURS SOP-13 Published by PCS on10/31/2019 4 illiitI of ~iami 0A,'-IEL J. ALFOMO Ci1v \,IJnagN MIAMi POLICE PATROL SUPPORT UNIT MARINE PATROL DETAll E1'. DORSEi\1ENT SHEET / · /- / /., .·. :: :, r-; ·~.: ::r, ~c._~J,~,;~ (j::'wrat;;iLC~---- ~ >•- • •; (', =i ,•' •,r V - - •._ .... ... .. ,---,,,- : ..,. ···~···/ ,•,J") It' . ' L, ~ ·::,. ~ O·_i:1.--t~-- &- - ·r·;=·;: act on ~,• •.__,o• r• , ,1 , r " ! o:c ,·, ()usrte, , Jt7 /- ,. .. C-0-c/:o_ _ _ 11- - c/-1 ~ ---------- --- -------- - ·. :- ~·~_; ::.t,on ~ ail Ccr;-:.-,1a~ ,\n n•,al Inspection---- <.4~ D2te ,1~ j- L ---···---- Detail Co~ rr.arcer ~., r , ''7 I I ,.