Turkey's Stance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Paul K. Kerr Analyst in Nonproliferation Mary Beth Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation August 1, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34248 Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Summary Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal probably consists of approximately 110-130 nuclear warheads, although it could have more. Islamabad is producing fissile material, adding to related production facilities, and deploying additional nuclear weapons and new types of delivery vehicles. Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is widely regarded as designed to dissuade India from taking military action against Pakistan, but Islamabad’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal, development of new types of nuclear weapons, and adoption of a doctrine called “full spectrum deterrence” have led some observers to express concern about an increased risk of nuclear conflict between Pakistan and India, which also continues to expand its nuclear arsenal. Pakistan has in recent years taken a number of steps to increase international confidence in the security of its nuclear arsenal. Moreover, Pakistani and U.S. officials argue that, since the 2004 revelations about a procurement network run by former Pakistani nuclear official A.Q. Khan, Islamabad has taken a number of steps to improve its nuclear security and to prevent further proliferation of nuclear-related technologies and materials. A number of important initiatives, such as strengthened export control laws, improved personnel security, and international nuclear security cooperation programs, have improved Pakistan’s nuclear security. However, instability in Pakistan has called the extent and durability of these reforms into question. Some observers fear radical takeover of the Pakistani government or diversion of material or technology by personnel within Pakistan’s nuclear complex. -

Duties: the Incumbent Serves As a Bodyguard in the Execution of Protective Security Operations for the U.S

U.S. Mission AMERICAN EMBASSY, NEW DELHI, INDIA Announcement Number: New Delhi-2019-084 Position Title: Bodyguard Regional Security Office (RSO) Opening Period: October 30, 2019 – November 5, 2019 Series/Position/Grade: LE-0701 /DLA-562042/05 Salary: Rs. 466,405 (annual salary) *Starting salary will be determined on the basis of qualifications and experience, and/or salary history. For More Info: Human Resources Office Mailing Address: Human Resources Office (Recruitment Team) C/o U.S. Embassy, Shantipath, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi – 110021. E-mail Address: [email protected] Who may apply: All Interested Candidates/All Sources Security Clearance Required: Local Security Certification Duration Appointment: Indefinite - subject to successful completion of probationary period Marketing Statement: We encourage you to read and understand the Eight (8) Qualities of Overseas Employees before you apply. Summary: The U.S. Embassy in New Delhi is seeking an individual for the position of Bodyguard in the Regional Security Office (RSO). The work schedule for this position: Full Time; 40 hours per week Start date: Candidate must be able to begin working within a reasonable period of time of receipt of agency authorization and/or clearances/certifications or their candidacy may end. Supervisory Position: No Duties: The incumbent serves as a Bodyguard in the execution of protective security operations for the U.S. Ambassador/Chief of Mission (COM), and other designated or visiting U.S. Government officials as directed. The incumbent will be under the supervision of the Bodyguard Supervisor and will be managed by the Regional Security Officer (RSO) to U.S. Embassy New Delhi in order to protect COM from harm and embarrassment. -

The Oath a Film by Laura Poitras

The Oath A film by Laura Poitras POV www.pbs.org/pov DISCUSSION GUIDe The Oath POV Letter frOm the fiLmmakers New YorK , 2010 I was first interested in making a film about Guantanamo in 2003, when I was also beginning a film about the war in Iraq. I never imagined Guantanamo would still be open when I finished that film, but sadly it was — and still is today. originally, my idea for the Oath was to make a film about some - one released from Guantanamo and returning home. In May 2007, I traveled to Yemen looking to find that story and that’s when I met Abu Jandal, osama bin Laden’s former bodyguard, driving a taxicab in Sana’a, the capital of Yemen. I wasn’t look - ing to make a film about Al-Qaeda, but that changed when I met Abu Jandal. Themes of betrayal, guilt, loyalty, family and absence are not typically things that come to mind when we imagine a film about Al-Qaeda and Guantanamo. Despite the dangers of telling this story, it compelled me. Born in Saudi Arabia of Yemeni parents, Abu Jandal left home in 1993 to fight jihad in Bosnia. In 1996 he recruited Salim Ham - dan to join him for jihad in Tajikistan. while traveling through Laura Poitras, filmmaker of the Oath . Afghanistan, they were recruited by osama bin Laden. Abu Jan - Photo by Khalid Al Mahdi dal became bin Laden's personal bodyguard and “emir of Hos - pitality.” Salim Hamdan became bin Laden’s driver. Abu Jandal ends up driving a taxi and Hamdan ends up at Guantanamo. -

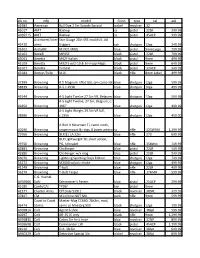

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

A Brief History of U.S.-Turkey Tensions (1960-2017) in Early October, the Arrest of a Turkish Employee at the U.S

THO FACTSHEET November 22, 2017 A Brief History of U.S.-Turkey Tensions (1960-2017) In early October, the arrest of a Turkish employee at the U.S. consulate in Istanbul prompted Washington to take an unprecedented, retaliatory measure. The U.S. announced it would suspend non-immigrant services in Turkey, its NATO ally of more than sixty years. Turkey responded in kind. While the crisis has recently been partially diffused, the spat has been called the lowest point in U.S.-Turkey relations.1 Yet the two governments have had their difficulties before. As a CFR task force described in a 2012 report, “a mythology surrounds U.S.-Turkey relations, suggesting that Washington 2 and Ankara have, through six decades, worked closely and with little friction.” While the overarching relationship remains strategic and important, here are some of the notably sour moments. June of 1964 Exchange of Letters Between President Late 1960’s Johnson and Prime Minister Inonu Sixth Fleet Clashes over Cyprus Turkish anti-American sentiment grew rapidly over ACTORS these years, particularly from left-wing elements U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, Turkey’s Prime concerned with Turkey’s perceived dependence Minister (PM) Ismet Inonu on the U.S. and NATO. Protests often focused on the presence of American servicemen in Turkey, CONTEXT the privileges they enjoyed, and a general desire Ethnic tensions and violence in Cyprus (home to a for a non-aligned Turkey (“bagimsiz Turkiye”). sizeable ethnic Turkish minority) led Turkey to Mass demonstrations and violent clashes broke consider an invasion of the island. out during several U.S. -

Applying Personality Theory to a Group of Police Bodyguards: a Physically Risky Prosocial Prototype?

Psicothema ISSN 0214 - 9915 CODEN PSOTEG 2002. Vol. 14, nº 2, pp. 387-392 Copyright © 2002 Psicothema Applying personality theory to a group of police bodyguards: a physically risky prosocial prototype? Montserrat Gomà-i-Freixanet and Andreas A. J. Wismeijer Autonomous University of Barcelona The aim of the present study is twofold. First, to present evidence in favour of the application of the dispositional model to police applicants and second to present evidence that police bodyguard mani- fest a personality profile similar to that of subjects engaged in activities that imply a high level of phy- sical risk of a prosocial kind. The sample consisted of 20 subjects, the complete Bodyguard Unit from the Autonomous Government of Catalunya. Subjects were administered the Eysenck Personality Ques- tionnaire (EPQ) and the Sensation Seeking Scale form V (SSS-V) from Zuckerman. The findings seem to favour the dispositional model and that the profile of a police bodyguard matches that of prosocials. The profile of a police bodyguard is characterized by being ambiverted, emotionally stable, with low scores on psychoticism and sensation seeking, and shows a distinctive characteristic expressed by a high sincerity and a low susceptibility to boredom. Perfil de personalidad de un grupo de policías-guardaespaldas: ¿Un prototipo de riesgo físico proso- cial? El objetivo del presente estudio es doble. Primero presentar evidencia a favor de la aplicación del modelo disposicional a los aspirantes a policía y segundo evidenciar que los policías-guardaespaldas manifiestan perfiles de personalidad similares a los de los sujetos que practican actividades que impli- can un nivel elevado de riesgo físico de tipo prosocial. -

Pakistan | Freedom House

Pakistan | Freedom House http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2012/pakistan About Us DONATE Blog Contact Us REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Donate FREEDOM IN THE WORLD Pakistan Pakistan Freedom in the World 2012 OVERVIEW: 2012 In 2011, tensions between the civilian government, the military and SCORES intelligence agencies, and the judiciary—and attempts by all three groups to exert greater control over policy formulation—continued to STATUS threaten the government’s stability and the consolidation of democracy in Pakistan. Societal discrimination and attacks against religious Partly minorities and women, as well as weak rule of law and impunity, remained issues of concern. Journalists and human rights defenders Free came under increased threat during the year, particularly those who FREEDOM RATING spoke out on Pakistan’s blasphemy laws or abuses by security and intelligence agencies. Freedom of expression also suffered due to official 4.5 attempts to censor online media content and greater self-censorship on sensitive issues. The army’s campaigns against Islamist militants in the CIVIL LIBERTIES tribal areas led to a range of human rights abuses, displacement of civilians, and retaliatory terrorist attacks across the country, while 5 violence in Balochistan and the city of Karachi worsened. POLITICAL RIGHTS Pakistan was created as a Muslim homeland during the partition of British India 4 in 1947, and the military has directly or indirectly ruled the country for much of its independent history. As part of his effort to consolidate power, military dictator Mohammad Zia ul-Haq amended the constitution in 1985 to allow the president to dismiss elected governments. -

My Experiences As a Member of President Lincoln's Bodyguard, 1863-65

My Experiences as a Member of President lincoln's Bodyguard, 1863-65 By Smith Stimmel Following a three-month enlistment in Compal'o/ H, 85th Ohio Volunteer Infantry in 1862, Smith Stimmel (1842 - 1935), then a student at Ohio Wesleyan University, volunteered to reenlist as a member of the Union Light Guard, assigned to protect the president. After President Linwlru assassination in April 1865, the troop brieRy acted as bodyguard to Andrew johnson, before the men were discharged from the service in time for Stimmel to return to Ohio Wesleyan that Fall The story of Stimmels experiences with Abraham Linwln was retold mal'o/ times and written down in several versions, including one published injanuary 1927 in North Dakotd Historic;i/ QuarterfyVolume 1, Number 2 (the predecessor to North Dakotd History). The following has been excerpted from that article. uring the summer of 1863, Governor Tod of Ohio Our duries were to guard the front entrance ro [he White D visited Washington concerning the interest of his state House grounds, and to act as an escort to the president in the war, and when he called at the White House he whenever he went OUt in his carriage, or when he rode on became impressed with the idea that the president was not horseback, as he often did during the summer. sufficiently protected. He applied to the War Department We enjoyed our summer work much more than we did for permission to organize a troop of one hundred mounted the winter guard duty. During the hot summer months the men to be assigned to duty as President Lincoln's mounted president lived our at [he Soldiers' Home, north of tl1e city, body guard . -

Stk No Mfg Model Finish Type Cal Ask 41983 American Bull Dog 2.5In

stk no mfg model finish type cal ask 41983 American Bull Dog 2.5in Suicide Special nickel revolver .32 42017 AMT Backup ss pistol .22LR 299.99 A939715 AMT Backup ss pistol .45ACP 399.99 Aramberri/Inter Star Guage 28in SXS mod/full, dbl 42470 arms triggers cch shotgun 12ga 249.99 35302 Astra/IIC M1921 (400) blue pistol 9mmLargo 299.99 43163 Benelli MP95E black pistol .22LR 799.99 43041 Beretta M92F Italian black pistol 9mm 499.99 43109 Beretta M92FS w/2-10 & 6 Hi-cap Mags black pistol 9mm 649.99 43107 Beretta Tomcat black pistol .32ACP 349.99 43184 Bertier/Tulle M16 black rifle 8mm Lebel 499.99 37399 Browning A 5 Magnum rifled bbl, syn camo stk blue shotgun 12ga 599.99 38839 Browning A-5 c.1938 blue shotgun 16ga 499.99 41944 Browning A-5 Light Twelve 27.5in VR, Belgium blue shotgun 12ga 599.99 A-5 Light Twelve, 27.5in, Belgium, c. 42850 Browning 1967 blue shotgun 12ga 499.99 A-5 Light Weight 29.5in VR full, 38986 Browning c.1956 blue shotgun 12ga 450.00 A-Bolt II Mountain Ti, camo stock, 40196 Browning scope mount & rings, 8 boxes ammo ss rifle .325WSM 1,399.99 29766 Browning BLR 81 LA 22in blue rifle .270 699.99 BLR Lightweight '81 short action, 29756 Browning PG, Schnabel blue rifle .358Win 749.99 42881 Browning Challenger blue pistol .22LR 549.99 42880 Browning Challenger w/x mag blue pistol .22LR 549.99 43070 Browning Lightning Sporting Clays Edition blue shotgun 12ga 749.99 35272 Browning M2000 w/poly choke blue shotgun 12ga 499.99 41249 Browning T-bolt blue rifle .22LR 499.99 36279 Browning T-Bolt Target blue rifle .17HMR 599.99 C.G. -

Abu Ubaida Al-Banshiri

Abu ‘Ubayda al-Banshiri Ali Amin ‘Ali al-Rashidi, better known as Abu ‘Ubayda al-Banshiri, was born in May of 1950 in Cairo, Egypt. At 46, he was al-Qa’ida’s military commander and second-in- command when he perished in a ferry accident on Lake Victoria on May 21, 1996. After acquiring his nom de guerre in Afghanistan while fighting the Soviets in the 1980s, al- Rashidi became a founding member of al-Qa’ida. He was intimately involved in al- Qa’ida’s expansion to the African continent, as well as the operational planning of their activities there. Al-Rashidi’s documented history begins with the assassination of Anwar al-Sadat in October of 1981. ‘Abd al-Hamid ‘Abd al-Salam, al-Rashidi’s future brother-in-law, was one of the several assassins along with a National Police officer.1 The assassins were members of an early incarnation of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, also called al-Jihad. In the ensuing crackdown on radicalism, al-Rashidi was dismissed from his job as a National Police officer, and arrested briefly for exhibiting extremist tendencies and having alleged ties to al-Jihad.2 In 1983, al-Rashidi married Hafsah Sa’d Rashwan, the sister of ‘Abd al-Salam’s wife. According to testimony provided by al-Rashidi’s wife, his involvement in jihad actually began shortly after this time. She states that they were in a poor financial situation two months after their marriage, during which time he was working in construction but contemplating a move to Saudi Arabia. -

12.025 Authorized Weapons

12.025 12.025 AUTHORIZED WEAPONS Reference: Ohio House Bill 12, Section 9 18 USC 926B, 926C, Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act of 2004 Ohio Revised Code 2901.01K, Law Enforcement Officer Ohio Revised Code 2923.12B, Carrying Concealed Weapons Ohio Revised Code 2923.12.1, Illegal Possession of Firearm in Liquor Permit Premises Ohio Revised Code 2923.12.2, Illegal Conveyance or Possession of Deadly Weapon or Dangerous Ordnance in School Safety Zone Ohio Revised Code 2923.12.3, Illegal Conveyance of Deadly Weapon or Dangerous Ordnance into Courthouse Ohio Revised Code 2923.126, Duties of Licensed Individual Ohio Revised Code 2923.15, Using Weapons While Intoxicated Procedure 12.020, Uniforms, Related Equipment, and Personal Grooming Procedure 12.545, Use of Force Procedure 12.550, Discharging of Firearms by Police Personnel Procedure 12.815, Court Appearances, Jury Duty, and Other Hearings Procedure 19.140, Outside Employment Definitions: Qualified Law Enforcement Officer – An employee of a governmental agency who: • is authorized by law to engage in or supervise the prevention, detection, investigation, or prosecution of, or the incarceration of any person for, any violation of law, and has statutory powers of arrest; • is authorized by the agency to carry a firearm; • is not the subject of any disciplinary action by the agency; • meets standards, if any, established by the agency which require the employee to regularly qualify in the use of a firearm; • is not under the influence of alcohol or another intoxicating or hallucinatory drug or substance; and • is not prohibited by Federal law from receiving a firearm Information: Supply Unit maintains a perpetual record of all Department owned and approved weapons. -

Gun Data Codes

GUN DATA CODES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1--MAKE (MAK) FIELD CODES ..................................................1 1.1 MAK FIELD ......................................................1 1.2 MAK FIELD CODE FOR U.S. MILITARY-ISSUE WEAPONS ...............1 1.3 MAK FIELD CODES FOR NONMILITARY U.S. GOVERNMENT WEAPONS ..1 1.4 MAK FIELD FOR FOREIGN MILITARY WEAPONS ......................1 1.5 MAK FIELD CODES ALPHABETICALLY BY MANUFACTURER ...........2 1.6 MAK FIELD CODES ALPHABETICALLY BY CODE ................... 156 2--CALIBER (CAL) FIELD CODES .............................................. 223 2.1 CAL FIELD CODES .............................................. 223 2.2 CAL FIELD CODES FOR SHOTGUNS ............................... 225 3--TYPE (TYP) FIELD CODES ................................................. 226 3.1 TYP FIELD CODES .............................................. 226 3.2 MOST FREQUENTLY USED TYP FIELD CODES ...................... 226 4--COLOR AND FINISH DATA ................................................. 230 MAK FIELD CODES GUN DATA CODES SECTION 1--MAKE (MAK) FIELD CODES 1.1 MAK FIELD Section 1.5 contains MAK Field codes listed alphabetically by gun manufacturer. If a make is not listed, the code ZZZ should be entered as characters 1 through 3 of the MAK Field with the actual manufacturer’s name appearing in positions 4 through 23. This manufacuter’s name will appear as entered in any record repose. If the MAK Field code is ZZZ and positions 4 through 23 are blank, the MAK Field will be translated as MAK/UNKNOWN in the record response. For unlisted makes, the CJIS Division staff should be contacted at 304-625-3000 for code assignments. Additional coding instructions can be found in the Gun File chapter of the NCIC 2000 Operating Manual. 1.2 MAK FIELD CODE FOR U.S. MILITARY-ISSUE WEAPONS For firearms (including surplus weapons) that are U.S.