A Scandinavian Town and Its Hinterland: the Case of Nya Lödöse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension: a Synthesis

CLIMATIC VARIABILITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSION: A SYNTHESIS CHRISTIAN PFISTER', RUDOLF BRAzDIL2 IInstitute afHistory, University a/Bern, Unitobler, CH-3000 Bern 9, Switzerland 2Department a/Geography, Masaryk University, Kotlar8M 2, CZ-61137 Bmo, Czech Republic Abstract. The introductory paper to this special issue of Climatic Change sununarizes the results of an array of studies dealing with the reconstruction of climatic trends and anomalies in sixteenth century Europe and their impact on the natural and the social world. Areas discussed include glacier expansion in the Alps, the frequency of natural hazards (floods in central and southem Europe and stonns on the Dutch North Sea coast), the impact of climate deterioration on grain prices and wine production, and finally, witch-hlllltS. The documentary data used for the reconstruction of seasonal and annual precipitation and temperatures in central Europe (Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic) include narrative sources, several types of proxy data and 32 weather diaries. Results were compared with long-tenn composite tree ring series and tested statistically by cross-correlating series of indices based OIl documentary data from the sixteenth century with those of simulated indices based on instrumental series (1901-1960). It was shown that series of indices can be taken as good substitutes for instrumental measurements. A corresponding set of weighted seasonal and annual series of temperature and precipitation indices for central Europe was computed from series of temperature and precipitation indices for Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic, the weights being in proportion to the area of each country. The series of central European indices were then used to assess temperature and precipitation anomalies for the 1901-1960 period using trmlsfer functions obtained from instrumental records. -

Historisk Tidskrift FÖR SKÅNE HALLAND OCH BLEKINGE

NR 3 2013 Historisk tidskrift FÖR SKÅNE HALLAND OCH BLEKINGE TEMANUMMER KNÄREDFREDEN 1613 F Ale Historisk tidskrift för Skåne, Halland och Blekinge utges av De skånska landskapens historiska och arkeologiska förening och Landsarkivet i Lund. Redaktör och ansvarig utgivare universitetslektor Gert Jeppsson, Lund. Redaktionskommitté Professor Lars Berggren, Lund l:e arkivarie fil. dr Elisabeth Reuterswärd, Lund Professor Sten Skansjö, Lund Fil.dr Bengt Söderberg, Lund Innehåll Sid. Mats Dahlbom: Fredsförhandlingarna i Knäred 1612-13 1 Steffen Heiberg: Christian IV og Freden i Knasrpd 15 Aktuellt om antikvariskt Minnet av freden i Knäred 1613 högtidlighållet i Laholm 30 En dös vid Ales stenar 31 TRYCKTJÄNST, 2013 Fredsförhandlingarna i Knäred 1612–13 Av Mats Dahlbom Civilingenjör, Falkenberg Det så kallade Kalmarkriget mellan Danmark och Sverige pågick 1611–13. I slutet av 1612 samlades fredsdelegationer från de båda länderna i Knäred (Knæröd) respektive Ulvsbäck. I den danska kommissionen ingick riksrådet Eske Brock och det är bland annat anteckningar från hans efterlämnade dagböcker som ligger till grund för denna uppsats. Eske Brock – »mannen med korsen» huvudgårdar och var därmed Danmarks Eske Brock (1560–1625) var en dansk adels- godsrikaste adelsman. Han utnyttjades av man med stora godsegendomar. Han var en Christian IV för olika uppdrag, bland annat av de ledande i danska rigsrådet och länsman deltog han i Flabäcksmötet 1603. Det som över Dronningborgs slott och län omkring gör honom sympatisk i våra ögon är att han Randers i Jylland, ett av Danmarks »fetaste» skrev omfattande dagböcker. I dessa kan man län. Som godsägare hade Brock också an- läsa om hans familj, hans affärstransaktioner, knytning till Skåneland. -

The Dark Unknown History

Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century 2 Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry Publications Series (Ds) can be purchased from Fritzes' customer service. Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer are responsible for distributing copies of Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry publications series (Ds) for referral purposes when commissioned to do so by the Government Offices' Office for Administrative Affairs. Address for orders: Fritzes customer service 106 47 Stockholm Fax orders to: +46 (0)8-598 191 91 Order by phone: +46 (0)8-598 191 90 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.fritzes.se Svara på remiss – hur och varför. [Respond to a proposal referred for consideration – how and why.] Prime Minister's Office (SB PM 2003:2, revised 02/05/2009) – A small booklet that makes it easier for those who have to respond to a proposal referred for consideration. The booklet is free and can be downloaded or ordered from http://www.regeringen.se/ (only available in Swedish) Cover: Blomquist Annonsbyrå AB. Printed by Elanders Sverige AB Stockholm 2015 ISBN 978-91-38-24266-7 ISSN 0284-6012 3 Preface In March 2014, the then Minister for Integration Erik Ullenhag presented a White Paper entitled ‘The Dark Unknown History’. It describes an important part of Swedish history that had previously been little known. The White Paper has been very well received. Both Roma people and the majority population have shown great interest in it, as have public bodies, central government agencies and local authorities. -

1580 Series Manual

Installation Guide Series 1580 Intercom Systems The Complete 1-on-2 Solution 2048 Mercer Road, Lexington, Kentucky 40511-1071 USA Phone: 859-233-4599 • Fax: 859-233-4510 Customer Toll-Free USA & Canada: 800-322-8346 www.audioauthority.com • [email protected] 2 Contents Introducing Series 1580 Intercom Systems 4 Series 1580 System Components 4 1580S and 1580HS Kits 4 Audio Installation 5 Lane Cable Information 6 Wiring 6 Advertising Messages 7 Traffic Sensors 8 Basic Calibration and Testing 9 Self Setup Mode 9 Troubleshooting Tips 9 Operation 10 Operator Guide 11 Using the 1550A Setup Tool 12 Advanced Calibration and Setup 12 Power User Tips 12 1550A Configuration Example 13 Definitions 14 Appendix 15 WARNINGS • Read these instructions before installing or using this product. • To reduce the risk of fire or electric shock, do not expose components to rain or moisture • This product must be installed by qualified personnel. • Do not expose this unit to excessive heat. • Clean the unit only with a dry or slightly dampened soft cloth. LIABILITY STATEMENT Every effort has been made to ensure that this product is free of defects. Audio Authority® cannot be held liable for the use of this hardware or any direct or indirect consequential damages arising from its use. It is the responsibility of the user of the hardware to check that it is suitable for his/her requirements and that it is installed correctly. All rights are reserved. No parts of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted by any form or means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written consent of the publisher. -

Miljörapport 2020 Lerkils Reningsverk Kungsbacka Kommun

Miljörapport 2020 Lerkils reningsverk Kungsbacka kommun Förvaltningen för Teknik Kungsbacka kommun Kungsbacka 2021 Miljörapport 2020 Lerkils ARV, Kungsbacka kommun INNEHÅLL INNEHÅLL ................................................................................................................................ 2 1. Verksamhetsbeskrivning ........................................................................................................ 3 1.1. Organisation ............................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Verksamhetsområde .................................................................................................. 3 1.3. Avloppsvattenrening ................................................................................................. 4 1.4. Slambehandling ......................................................................................................... 5 1.5. Driftövervakning och styrning ................................................................................. 5 1.6. Kemikaliehantering ................................................................................................... 6 1.7. Ledningsnät och pumpstationer ............................................................................... 6 1.8. Verksamhetens påverkan på miljön ........................................................................ 8 2. Tillstånd ................................................................................................................................. -

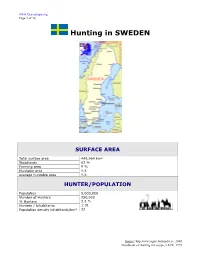

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

Ladda Ner Tävlingsdata Från 2001-2017

Kungsbacka River År Set Klass Plac Tid Nr Deltagare 1 Deltagare 2 Ort Lag / Förening / Företag 2017 Dam C2 Damer Elit 1 03:11:41 487 Anette Johansson Helen Johansson Fjärås / Kungsbacka Gretas Vänner C2 Damer Motionär 1 03:18:30 229 Mia Salmi Karin Hedelin-Lundén Onsala Pocahontas 2 03:23:04 244 Mia Falk Sabina Millan Kungsbacka / Onsala SaMia Paddle •Queen 3 03:23:57 276 Emma Lanzky Louise Erneholm Kungsbacka / Fjärås (tom) 4 03:28:37 228 Maria Huttqvist Martina Larsson Kungsbacka / Fotskäl (tom) 5 03:34:52 247 Susan Heemskerk Helene Svensson Örby (tom) 6 03:47:24 279 Veronica Aldorsson Rebecca Aldorsson Göteborg Kung Julien & CO 7 03:52:48 246 Sofie Fahl Anna Alexandersson Kungsbacka Sopranas 8 04:08:14 227 Linda Heed Nina Gulin Onsala / Kungsbacka (tom) 9 04:22:26 245 Gunilla Wennergren Jenny Steen Fjärås / Onsala Team WeSt 10 04:22:34 241 Amanda Hansson Sara Wendélius Kungsbacka Walter Hansson EL 11 04:37:02 230 Johanna Rasmusson Jenny Rasmusson Göteborg (tom) 12 04:41:55 500 Linda Andreasson Pia Wennerbäck Kungsbacka Raska töser 13 05:08:57 255 Nina Ingvarsson Emma Scherman Kungsbacka Team Rockstar 5 Herr C2 Herrar Elit 1 02:21:24 449 Geir Inge Folkestad Ulf Tyrén Anderstorp Isaberg Multisport 2 02:32:58 483 Tommy Eneroth Morgan Börjesson Kungsbacka / Fjärås Myra Golf Lag 2 3 02:36:29 472 Stefan Anerönn Ingemar Blom Kungälv / Lindome Gnellspikes Multisport Club 4 02:40:40 466 Kjell Hultén Benny Kjellman Fjärås K. Snickeri & Teknik AB 5 02:43:29 486 Victor Wallin Jesper Alderin Kungsbacka / Borås Myra Golf Lag 4 6 02:47:35 454 Doug -

Spring 2020 Course Syllabus LDST 340 Late Medieval and Early Modern Leadership: the Tudor Dynasty Peter Iver Kaufman [email protected]; 289-8003

Spring 2020 Course Syllabus LDST 340 Late Medieval and Early Modern Leadership: The Tudor Dynasty Peter Iver Kaufman [email protected]; 289-8003 -- I’m tempted to say that this course will bring you as close as GAME OF THRONES to political reality yet far removed from the concerns that animate and assignments that crowd around your other courses. We’ll spend the first several weeks sifting what’s been said by and about figures who played large parts in establishing the Tudor dynasty from 1485. You received my earlier emails and know that you’re responsible for starting what’s been described as a particularly venomous account of the reign of the first Tudor monarch, King Henry VII (1485 -1509). We’ll discuss your impressions during the first class. You’ll find the schedule for other discussions below. We meet once each week. Instructor’s presentations, breakout group conversations, film clips, plenary discussions, and conferences about term papers should make the time pass somewhat quickly and productively. Your lively, informed participation will make this class a success. I count on it, and your final grades will reflect it (or your absences and failure to prepare thoughtful and coherent responses to the assignments). Final grades will be computed on the basis of your performances on the two short papers (800 words) that you elect to submit. Papers will be submitted by 10 AM on the day of the class in which the topics are scheduled to be discussed. For each paper, you can earn up to ten points (10% of your final grade). -

Baltic Towns030306

The State and the Integration of the Towns of the Provinces of the Swedish Baltic Empire The Purpose of the Paper1 between 1561 and 1660, Sweden expanded Dalong the coasts of the Baltic Sea and throughout Scandinavia. Sweden became the dominant power in the Baltics and northern Europe, a position it would maintain until the early eighteenth century. At the same time, Swedish society was experiencing a profound transformation. Sweden developed into a typical European early modern power-state with a bureaucracy, a powerful mili- tary organization, and a peasantry bending under taxes and conscription. The kingdom of Sweden also changed from a self-contained country to an important member of the European economy. During this period the Swedish urban system developed as well. From being one of the least urbanized European countries with hardly more than 40 towns and an urbanization level of three to four per cent, Sweden doubled the number of towns and increased the urbanization level to almost ten per cent. The towns were also forced by the state into a staple-town system with differing roles in fo- reign and domestic trade, and the administrative and governing systems of the towns were reformed according to royal initiatives. In the conquered provinces a number of other towns now came under Swe- dish rule. These towns were treated in different ways by the state, as were the pro- vinces as a whole. While the former Danish and Norwegian towns were complete- ly incorporated into the Swedish nation, the German and most of the east Baltic towns were not. -

An Ambiguous Relationship – Sweden and Finland Before 1809

AN AMBIGUOUS RELATIONSHIP Jonas Nordin Jonas NORDin 21 AN ambiguous relationship – SWEDen anD FinlanD before 1809 The nature of the relationship between Sweden and Finland as parts of the same realm before 1809 is a matter of scholarly debate. I have treated the sub- ject in various contexts, and I do not think I plume myself if I assert that my research has attracted some attention and also provoked a lot of discussion. Not all debaters have supported my view, and the purpose of the following elucidation is to answer some of the criticism. As a rule I find that the objec- tions to my view are based on misunderstandings and therefore often miss the point. The texts that have caused most debate are an article published in Scandia in 1998 and my dissertation, presented two years later. In the article I analyse the relationship between Sweden and Finland in the 1700s by trying to fit the Finnish nation into Anthony D. Smith’s concept of ethnie. In the dissertation I treat the same issue on a more conceptual level. My aim there is to undertake an empirical rather than theoretical analysis. Not everyone has apprehended this difference, and although the results more or less correspond, one has to consider that the two studies are based on different methods that are not nec- essarily interchangeable.1 These investigations came about in a certain historiographic context. For a long time the prevailing view in the post-war period was that not only nation- alism but also the nation as such were quite modern inventions. -

Historical Aquaculture in Northern Europe

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312033065 Historical Aquaculture in Northern Europe Book · December 2016 CITATION READS 1 2,326 1 author: Ingvar Svanberg Uppsala University 144 PUBLICATIONS 979 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Ethnoichthyology of fresh water fish: a neglected research field View project The Kazakh (Qazaq) Minority of Xinjiang 1979 - View project All content following this page was uploaded by Ingvar Svanberg on 03 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Historical Aquaculture in Northern Europe Historical Aquaculture in Northern Europe Edited by Madeleine Bonow Håkan Olsén and Ingvar Svanberg Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors Cover image: Pond Crucian Carp (Dammruda) from Mörkö, illustrated by Wilhelm von Wright and taken from Skandinaviens fiskar: målade efter lefvande exemplar och ritade på sten Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söner, 1836–1857 Cover: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2016 Research Report 2016:1 ISBN 978–91–87843–62–4 Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ -

The Catholic Plots Early Life 1560 1570 1580 1590 1600

Elizabethan England: Part 1 – Elizabeth’s Court and Parliament Family History Who had power in Elizabethan England? Elizabeth’s Court Marriage The Virgin Queen Why did Parliament pressure Elizabeth to marry? Reasons Elizabeth chose Group Responsibilities No. of people: not to marry: Parliament Groups of people in the Royal What did Elizabeth do in response by 1566? Who was Elizabeth’s father and Court: mother? What happened to Peter Wentworth? Council Privy What happened to Elizabeth’s William Cecil mother? Key details: Elizabeth’s Suitors Lieutenants Robert Dudley Francis Duke of Anjou King Philip II of Spain Who was Elizabeth’s brother? Lord (Earl of Leicester) Name: Key details: Key details: Key details: Religion: Francis Walsingham: Key details: Who was Elizabeth’s sister? Justices of Name: Peace Nickname: Religion: Early Life 1560 1570 1580 1590 1600 Childhood 1569 1571 1583 1601 Preparation for life in the Royal The Northern Rebellion The Ridolfi Plot The Throckmorton Plot Essex’s Rebellion Court: Key conspirators: Key conspirators: Key conspirators: Key people: Date of coronation: The plan: The plan: The plan: What happened? Age: Key issues faced by Elizabeth: Key events: Key events: Key events: What did Elizabeth show in her response to Essex? The Catholic Plots Elizabethan England: Part 2 – Life in Elizabethan Times Elizabethan Society God The Elizabethan Theatre The Age of Discovery Key people and groups: New Companies: New Technology: What was the ‘Great Chain of Being’? Key details: Explorers and Privateers Francis Drake John Hawkins Walter Raleigh Peasants Position Income Details Nobility Reasons for opposition to the theatre: Gentry 1577‐1580 1585 1596 1599 Drake Raleigh colonises ‘Virginia’ in Raleigh attacks The Globe Circumnavigation North America.