Baltic Towns030306

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Unknown History

Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century 2 Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry Publications Series (Ds) can be purchased from Fritzes' customer service. Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer are responsible for distributing copies of Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry publications series (Ds) for referral purposes when commissioned to do so by the Government Offices' Office for Administrative Affairs. Address for orders: Fritzes customer service 106 47 Stockholm Fax orders to: +46 (0)8-598 191 91 Order by phone: +46 (0)8-598 191 90 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.fritzes.se Svara på remiss – hur och varför. [Respond to a proposal referred for consideration – how and why.] Prime Minister's Office (SB PM 2003:2, revised 02/05/2009) – A small booklet that makes it easier for those who have to respond to a proposal referred for consideration. The booklet is free and can be downloaded or ordered from http://www.regeringen.se/ (only available in Swedish) Cover: Blomquist Annonsbyrå AB. Printed by Elanders Sverige AB Stockholm 2015 ISBN 978-91-38-24266-7 ISSN 0284-6012 3 Preface In March 2014, the then Minister for Integration Erik Ullenhag presented a White Paper entitled ‘The Dark Unknown History’. It describes an important part of Swedish history that had previously been little known. The White Paper has been very well received. Both Roma people and the majority population have shown great interest in it, as have public bodies, central government agencies and local authorities. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Invasions, Insurgency and Interventions: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark 1654 - 1658. A Dissertation Presented by Christopher Adam Gennari to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Christopher Adam Gennari 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Christopher Adam Gennari We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Ian Roxborough – Dissertation Advisor, Professor, Department of Sociology. Michael Barnhart - Chairperson of Defense, Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of History. Gary Marker, Professor, Department of History. Alix Cooper, Associate Professor, Department of History. Daniel Levy, Department of Sociology, SUNY Stony Brook. This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School """"""""" """"""""""Lawrence Martin "" """""""Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Invasions, Insurgency and Intervention: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark. by Christopher Adam Gennari Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 "In 1655 Sweden was the premier military power in northern Europe. When Sweden invaded Poland, in June 1655, it went to war with an army which reflected not only the state’s military and cultural strengths but also its fiscal weaknesses. During 1655 the Swedes won great successes in Poland and captured most of the country. But a series of military decisions transformed the Swedish army from a concentrated, combined-arms force into a mobile but widely dispersed force. -

Miljörapport 2020 Lerkils Reningsverk Kungsbacka Kommun

Miljörapport 2020 Lerkils reningsverk Kungsbacka kommun Förvaltningen för Teknik Kungsbacka kommun Kungsbacka 2021 Miljörapport 2020 Lerkils ARV, Kungsbacka kommun INNEHÅLL INNEHÅLL ................................................................................................................................ 2 1. Verksamhetsbeskrivning ........................................................................................................ 3 1.1. Organisation ............................................................................................................... 3 1.2. Verksamhetsområde .................................................................................................. 3 1.3. Avloppsvattenrening ................................................................................................. 4 1.4. Slambehandling ......................................................................................................... 5 1.5. Driftövervakning och styrning ................................................................................. 5 1.6. Kemikaliehantering ................................................................................................... 6 1.7. Ledningsnät och pumpstationer ............................................................................... 6 1.8. Verksamhetens påverkan på miljön ........................................................................ 8 2. Tillstånd ................................................................................................................................. -

Et Eksempel På Havplanlægning På Tværs Af Kommunegrænser I Blekinge

Inter-municipal MSP Case study Blekinge Seaplanspace seminar Aalborg University, 20 February 2020 Henrik Nilsson –World Maritme University The role of municipalities in MSP u 82 coastal municipalities in Sweden u Municipalities responsible for spatial planning on land and sea areas within their boundaries u Municipal border extends to outer limit of territorial sea. u Comprehensive plans – guiding plans Marine Spatial Plan Blekinge Inter-municipal plan between 4 municipalities: • Sölvesborg • Karlshamn • Ronneby • Karlskrona • Starts at 300m from baseline – outer border of TS • Guiding plan • Adopted in autumn 2019 Development process u 2014 - Initiative taken by County Administrative Board and Blekinge Archipelago Biosphere Reserve u 2015 – Municipal inventory of data and knowledge needed for development of MSP. u 2016/2017 – Funding from Swam to continue inventory and development of plan. u Set-up of organisational structure u Working group with representatives from each municipality (planners) u Steering group at each municipality (planners, environmental strategist, port representatives etc) Stakeholder consultations 2017 u Thematic consultations: 1. Fisheries,aquaculture,energy 2. Shipping,infrastructure and extraction of natural resources 3. Nature protection, leisure and tourism 4. Defense, climate, cultural heritage Interest matrix Compatible use Limited risk of conflct Risk of conflict Clear risk of conflict Interactive GiS map • Fisheries • Aquaculture • Shipping • Defense • Nature • Energy • Infrastructure • Exploitation of natural resources • Recreation • Culture Key benefits of cooperation in inter- municipal MSP planning u Shared knowledge and competences u Ecological considerations are done from a more holistic perspective u Interest conflicts and subsequent solutions are easier to identify u Common knowledge gaps are identified as well as needs for additional competences Thank you!. -

Climate in Sweden During the Past Millennium - Evidence from Proxy Data, Instrumental Data and Model Simulations

Technical Report TR-06-35 Climate in Sweden during the past millennium - Evidence from proxy data, instrumental data and model simulations Anders Moberg, Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University Isabelle Gouirand, Kristian Schoning, Barbara Wohlfarth Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University Erik Kjellstrom, Markku Rummukainen, Rossby Centre, SMHI Rixt de Jong, Department of Quaternary Geology, Lund University Hans Linderholm, Department of Earth Sciences, Goteborg University Eduardo Zorita, GKSS Research Centre, Geesthacht, Germany Svensk Karnbranslehantering AB Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co December 2006 Box 5864 SE-102 40 Stockholm Sweden Tel 08-459 84 00 +46 8 459 84 00 Fax 08-661 57 19 +46 8 661 57 19 Climate in Sweden during the past millennium - Evidence from proxy data, instrumental data and model simulations Anders Moberg, Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University Isabelle Gouirand, Kristian Schoning, Barbara Wohlfarth Department of Physical Geography and Quaternary Geology, Stockholm University Erik Kjellstrom, Markku Rummukainen, Rossby Centre, SMHI Rixt de Jong, Department of Quaternary Geology, Lund University Hans Linderholm, Department of Earth Sciences, Goteborg University Eduardo Zorita, GKSS Research Centre, Geesthacht, Germany December 2006 This report concerns a study which was conducted for SKB. The conclusions and viewpoints presented in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily coincide with those of the client. A pdf version of this document can be downloaded from www.skb.se Summary Knowledge about climatic variations is essential for SKB in its safety assessments of a geologi cal repository for spent nuclear waste. -

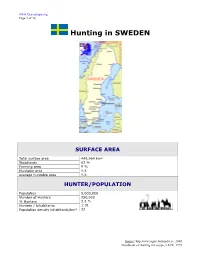

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

Blekinge Bohuslän Dalarna Tema: Sveriges Landskap FACIT

Tema: Sveriges landskap FACIT: Landskapsutmaningen Blekinge 1. Kungsljus, ek och ekoxe 2. Mörrumsån 3. Sveriges trädgård 4. Bilar, maskiner, telesystem, kök, badrum samt utrustning för sportfiske 5. Gubben Rosenbom är egentligen en tiggarsparbössa som samlar ihop pengar till fattiga i staden. 6. En skärgård är ett område utanför en kust med många öar, skär och grund. Utmaning 2: -Stirr är det uppväxtstadium av fiskarten lax som föregår smoltstadiet, då den vandrar ut i havet. Den känns igen på en rad mörka tvärband längs sidan. -Smolt är ett uppväxtstadium hos lax, som kommer mellan stirr och blanklax. Smolt är silver- färgad med svarta prickar och har ändrat sina fysiologiska processer för att klara vandringen från rinnande vatten ut i havet. -Blanklax är det ljust färgade havsstadiet av lax. -Grilse är lax som återvänder till sötvatten efter mindre än två års vistelse i havet. -Vraklax är en utlekt individ av fiskarten lax. Bohuslän 1. Knubbsäl och vildkaprifol 2. Tjörn och Orust 3. Bronsåldern 4. Granit är mellan en halv miljard till cirka två miljarder gammalt. 5. Den använder klorna till att krossa skalet på snäckor och musslor. 6. Tran är en olja från kokning av bland annat fisk och säl som används vid bearbetning av läder. Förr användes den även som bränsle i oljelampor. Dalarna 1. Berguv och ängsklocka 2. Siljan 3. Nusnäs 4. Det var bättre bete för husdjuren vid fäbodarna på sommaren. 5. Skogsindustri (papper, pappersmassa, trävaror) järn- och stålindustri för tillverkning av plåt, verkstadsindustri 6. Transtrandsfjällen facit_utmaningen_sveriges landskap Tema: Sveriges landskap FACIT: Landskapsutmaningen Dalsland 1. Korp och förgätmigej 2. -

Mischtext Und Zweisprachigkeit

Pre-print version from: Companion to Mysticism and Devotion in Northern Germany in the Late Middle Ages, ed. by Elizabeth Andersen, Henrike Lähnemann and Anne Simon (Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition 44), Leiden 2013, pp. 317-341. ISBN 9789004257931 With thanks to Brill for their permission to publish the pre-print version online Bilingual Devotion: The Prayer Books from the Lüneburg Convents Henrike Lähnemann The prayer books from Medingen and other Lüneburg convents offer a unique insight into the processes of religious and linguistic transformation which shaped devotion through writing in Northern Germany in the late Middle Ages.1 In the copious manuscript output sparked by the reform movement in the second half of the fifteenth century, Latin and Low German religious tra- ditions are merged and mixed: Latin liturgy, monastic culture and vernacular songs contribute to the rich texture that characterizes the Northern German bilingual prayer books. The Church cal- endar provides the timeframe and the liturgical pieces the musical ground for a polyphonic writ- ing to which the nuns each add their own arrangements and improvisation by translating, ampli- fying and adapting Latin and Low German textual elements. None of the prayer books contain new mystical texts but all of them draw on bridal mysticism to enrich the texture of the prose composition, often to the point where it turns into assonating, rhythmical text blocks. When, for example, in the Easter Meditation and Poem (in the appendix), the innige sele [devout soul] is en- couraged to dance with David, court Christ or meet with Mary, elements of the language of bridal mysticism are fused with formulations from Latin sequences and vernacular hymns. -

The Strange Revival of Bicameralism

The Strange Revival of Bicameralism Coakley, J. (2014). The Strange Revival of Bicameralism. Journal of Legislative Studies, 20(4), 542-572. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2014.926168 Published in: Journal of Legislative Studies Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2014 Taylor & Francis. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 Published in Journal of Legislative Studies , 20 (4) 2014, pp. 542-572; doi: 10.1080/13572334.2014.926168 THE STRANGE REVIVAL OF BICAMERALISM John Coakley School of Politics and International Relations University College Dublin School of Politics, International Studies and Philosophy Queen’s University Belfast [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT The turn of the twenty-first century witnessed a surprising reversal of the long-observed trend towards the disappearance of second chambers in unitary states, with 25 countries— all but one of them unitary—adopting the bicameral system. -

Småland‑Blekinge 2019 Monitoring Progress and Special Focus on Migrant Integration

OECD Territorial Reviews SMÅLAND-BLEKINGE OECD Territorial Reviews Reviews Territorial OECD 2019 MONITORING PROGRESS AND SPECIAL FOCUS ON MIGRANT INTEGRATION SMÅLAND-BLEKINGE 2019 MONITORING PROGRESS AND PROGRESS MONITORING SPECIAL FOCUS ON FOCUS SPECIAL MIGRANT INTEGRATION MIGRANT OECD Territorial Reviews: Småland‑Blekinge 2019 MONITORING PROGRESS AND SPECIAL FOCUS ON MIGRANT INTEGRATION This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Please cite this publication as: OECD (2019), OECD Territorial Reviews: Småland-Blekinge 2019: Monitoring Progress and Special Focus on Migrant Integration, OECD Territorial Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311640-en ISBN 978-92-64-31163-3 (print) ISBN 978-92-64-31164-0 (pdf) Series: OECD Territorial Reviews ISSN 1990-0767 (print) ISSN 1990-0759 (online) The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. Photo credits: Cover © Gabriella Agnér Corrigenda to OECD publications may be found on line at: www.oecd.org/about/publishing/corrigenda.htm. © OECD 2019 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. -

Develop Sweden! the EU Structural and Investment Funds in Sweden 2014–2020

2014 –2020 Develop Sweden! The EU Structural and Investment Funds in Sweden 2014–2020 Swedish Board The Swedish of Agriculture ESF Council © Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth Production: Ordförrådet Stockholm, mars 2016 Info 0617 ISBN 978-91-87903-40-3 DEVELOP SWEDEN Develop Sweden! The European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) provide opportunities for major investments to develop regions, individu- als and enterprises throughout Sweden. A total of SEK 67 billion (including public and/or private co-financ- ing) is to be invested in the years 2014–2020. In order for this fund- ing to have the greatest possible benefit, Sweden has agreed with the European Commission (EC) on certain priorities: • Enhance competitiveness, knowledge and innovation • Sustainable and efficient utilisation of resources for sustainable growth • Increase employment, enhance employability and improve access to the labour market In the years 2014–2020, Sweden will be participating in 27 pro- grammes financed by one of four ESIF. This brochure provides an overview of the programmes under the ESIF that concern Sweden, and the programmes in which Swedish organisations, government agencies and enterprises can participate. For those requiring more in-depth information, for example in order to seek funding, it includes references to the responsible government agencies and organisations. This brochure has been produced collaboratively by the Managing Authorities of the ESIF in Sweden. For more information about these four funds and 27 programmes, visit www.eufonder.se 1 Contents EU Structural and Investment Funds in Sweden 2014–2020 .................................................. 3 European Social Fund .............................................................................................................. 6 European Regional Development Fund ................................................................................... 8 Upper-North Sweden .............................................................................................................