How England Was Prepared for Persecution and Defended from Martyrdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension: a Synthesis

CLIMATIC VARIABILITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSION: A SYNTHESIS CHRISTIAN PFISTER', RUDOLF BRAzDIL2 IInstitute afHistory, University a/Bern, Unitobler, CH-3000 Bern 9, Switzerland 2Department a/Geography, Masaryk University, Kotlar8M 2, CZ-61137 Bmo, Czech Republic Abstract. The introductory paper to this special issue of Climatic Change sununarizes the results of an array of studies dealing with the reconstruction of climatic trends and anomalies in sixteenth century Europe and their impact on the natural and the social world. Areas discussed include glacier expansion in the Alps, the frequency of natural hazards (floods in central and southem Europe and stonns on the Dutch North Sea coast), the impact of climate deterioration on grain prices and wine production, and finally, witch-hlllltS. The documentary data used for the reconstruction of seasonal and annual precipitation and temperatures in central Europe (Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic) include narrative sources, several types of proxy data and 32 weather diaries. Results were compared with long-tenn composite tree ring series and tested statistically by cross-correlating series of indices based OIl documentary data from the sixteenth century with those of simulated indices based on instrumental series (1901-1960). It was shown that series of indices can be taken as good substitutes for instrumental measurements. A corresponding set of weighted seasonal and annual series of temperature and precipitation indices for central Europe was computed from series of temperature and precipitation indices for Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic, the weights being in proportion to the area of each country. The series of central European indices were then used to assess temperature and precipitation anomalies for the 1901-1960 period using trmlsfer functions obtained from instrumental records. -

Hate Speech and Persecution: a Contextual Approach

V anderbilt Journal of Transnational Law VOLUME 46 March 2013 NUMBER 2 Hate Speech and Persecution: A Contextual Approach Gregory S. Gordon∗ ABSTRACT Scholarly work on atrocity-speech law has focused almost exclusively on incitement to genocide. But case law has established liability for a different speech offense: persecution as a crime against humanity (CAH). The lack of scholarship regarding this crime is puzzling given a split between the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia on the issue of whether hate speech alone can serve as an actus reus for CAH-persecution. This Article fills the gap in the literature by analyzing the split between the two tribunals and concluding that hate speech alone may be the basis for CAH- persecution charges. First, this is consistent with precedent going as far back as the Nuremberg trials. Second, it takes into account the CAH requirement that the speech be uttered as part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population. Third, the defendant must be aware that his speech ∗ Associate Professor of Law, University of North Dakota School of Law, and Director, UND Center for Human Rights and Genocide Studies; former Prosecutor, International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda; J.D., UC Berkeley School of Law. The author would like to thank his research assistants, Lilie Schoenack and Moussa Nombre, for outstanding work. The piece also benefited greatly from the insights of Kevin Jon Heller, Joseph Rikhof, and Benjamin Brockman-Hawe. Thanks, as always, to my family, especially my wife, whose incredible support made this article possible. -

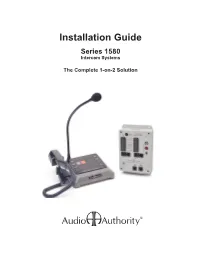

1580 Series Manual

Installation Guide Series 1580 Intercom Systems The Complete 1-on-2 Solution 2048 Mercer Road, Lexington, Kentucky 40511-1071 USA Phone: 859-233-4599 • Fax: 859-233-4510 Customer Toll-Free USA & Canada: 800-322-8346 www.audioauthority.com • [email protected] 2 Contents Introducing Series 1580 Intercom Systems 4 Series 1580 System Components 4 1580S and 1580HS Kits 4 Audio Installation 5 Lane Cable Information 6 Wiring 6 Advertising Messages 7 Traffic Sensors 8 Basic Calibration and Testing 9 Self Setup Mode 9 Troubleshooting Tips 9 Operation 10 Operator Guide 11 Using the 1550A Setup Tool 12 Advanced Calibration and Setup 12 Power User Tips 12 1550A Configuration Example 13 Definitions 14 Appendix 15 WARNINGS • Read these instructions before installing or using this product. • To reduce the risk of fire or electric shock, do not expose components to rain or moisture • This product must be installed by qualified personnel. • Do not expose this unit to excessive heat. • Clean the unit only with a dry or slightly dampened soft cloth. LIABILITY STATEMENT Every effort has been made to ensure that this product is free of defects. Audio Authority® cannot be held liable for the use of this hardware or any direct or indirect consequential damages arising from its use. It is the responsibility of the user of the hardware to check that it is suitable for his/her requirements and that it is installed correctly. All rights are reserved. No parts of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted by any form or means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written consent of the publisher. -

Poor Relief and the Church in Scotland, 1560−1650

George Mackay Brown and the Scottish Catholic Imagination Scottish Religious Cultures Historical Perspectives An innovative study of George Mackay Brown as a Scottish Catholic writer with a truly international reach This lively new study is the very first book to offer an absorbing history of the uncharted territory that is Scottish Catholic fiction. For Scottish Catholic writers of the twentieth century, faith was the key influence on both their artistic process and creative vision. By focusing on one of the best known of Scotland’s literary converts, George Mackay Brown, this book explores both the Scottish Catholic modernist movement of the twentieth century and the particularities of Brown’s writing which have been routinely overlooked by previous studies. The book provides sustained and illuminating close readings of key texts in Brown’s corpus and includes detailed comparisons between Brown’s writing and an established canon of Catholic writers, including Graham Greene, Muriel Spark and Flannery O’Connor. This timely book reveals that Brown’s Catholic imagination extended far beyond the ‘small green world’ of Orkney and ultimately embraced a universal human experience. Linden Bicket is a Teaching Fellow in the School of Divinity in New College, at the University of Edinburgh. She has published widely on George Mackay Brown Linden Bicket and her research focuses on patterns of faith and scepticism in the fictive worlds of story, film and theatre. Poor Relief and the Cover image: George Mackay Brown (left of crucifix) at the Italian Church in Scotland, Chapel, Orkney © Orkney Library & Archive Cover design: www.hayesdesign.co.uk 1560−1650 ISBN 978-1-4744-1165-3 edinburghuniversitypress.com John McCallum POOR RELIEF AND THE CHURCH IN SCOTLAND, 1560–1650 Scottish Religious Cultures Historical Perspectives Series Editors: Scott R. -

Structural Violence Against Children in South Asia © Unicef Rosa 2018

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA © UNICEF ROSA 2018 Cover Photo: Bangladesh, Jamalpur: Children and other community members watching an anti-child marriage drama performed by members of an Adolescent Club. © UNICEF/South Asia 2016/Bronstein The material in this report has been commissioned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) regional office in South Asia. UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this work do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Permission to copy, disseminate or otherwise use information from this publication is granted so long as appropriate acknowledgement is given. The suggested citation is: United Nations Children’s Fund, Structural Violence against Children in South Asia, UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2018. STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNICEF would like to acknowledge Parveen from the University of Sheffield, Drs. Taveeshi Gupta with Fiona Samuels Ramya Subrahmanian of Know Violence in for their work in developing this report. The Childhood, and Enakshi Ganguly Thukral report was prepared under the guidance of of HAQ (Centre for Child Rights India). Kendra Gregson with Sheeba Harma of the From UNICEF, staff members representing United Nations Children's Fund Regional the fields of child protection, gender Office in South Asia. and research, provided important inputs informed by specific South Asia country This report benefited from the contribution contexts, programming and current violence of a distinguished reference group: research. In particular, from UNICEF we Susan Bissell of the Global Partnership would like to thank: Ann Rosemary Arnott, to End Violence against Children, Ingrid Roshni Basu, Ramiz Behbudov, Sarah Fitzgerald of United Nations Population Coleman, Shreyasi Jha, Aniruddha Kulkarni, Fund Asia and the Pacific region, Shireen Mary Catherine Maternowska and Eri Jejeebhoy of the Population Council, Ali Mathers Suzuki. -

William Herle's Report of the Dutch Situation, 1573

LIVES AND LETTERS, VOL. 1, NO. 1, SPRING 2009 Signs of Intelligence: William Herle’s Report of the Dutch Situation, 1573 On the 11 June 1573 the agent William Herle sent his patron William Cecil, Lord Burghley a lengthy intelligence report of a ‘Discourse’ held with Prince William of Orange, Stadtholder of the Netherlands.∗ Running to fourteen folio manuscript pages, the Discourse records the substance of numerous conversations between Herle and Orange and details Orange’s efforts to persuade Queen Elizabeth to come to the aid of the Dutch against Spanish Habsburg imperial rule. The main thrust of the document exhorts Elizabeth to accept the sovereignty of the Low Countries in order to protect England’s naval interests and lead a league of protestant European rulers against Spain. This essay explores the circumstances surrounding the occasion of the Discourse and the context of the text within Herle’s larger corpus of correspondence. In the process, I will consider the methods by which the study of the material features of manuscripts can lead to a wider consideration of early modern political, secretarial and archival practices. THE CONTEXT By the spring of 1573 the insurrection in the Netherlands against Spanish rule was seven years old. Elizabeth had withdrawn her covert support for the English volunteers aiding the Dutch rebels, and was busy entertaining thoughts of marriage with Henri, Duc d’Alençon, brother to the King of France. Rejecting the idea of French assistance after the massacre of protestants on St Bartholomew’s day in Paris the previous year, William of Orange was considering approaching the protestant rulers of Europe, mostly German Lutheran sovereigns, to form a strong alliance against Spanish Catholic hegemony. -

An O Ve Rv Iew 10 Points on Religious Persecution

PM GLYNN INSTITUTE An overview 10 points on Religious Persecution CRICOS registered provider: 00004G Religious freedom: a question of survival “In the Central African Republic, religious Many instances of religious persecution freedom is not a concept; it is a question have been underreported or neglected of survival. The idea is not whether one completely, especially in Western media. is more or less comfortable with the 10 points on Religious Persecution is ideological foundations underpinning intended to draw attention to the issue religious freedom; rather, the issue is and raise awareness on the plight faced how to avoid a bloodbath!” For Cardinal by many, most often minority religious Dieudonné Nzapalainga, the Archbishop groups. of Bangui in the Central African Republic, At a time when advocacy for minority this is a sad and harsh reality; a reality that groups is increasing, it would be is faced by millions of people on a global encouraging to see similar support for scale today. religious minority groups who face When religious freedom is undervalued, persecution because of their faith and ignored, discouraged or targeted, religious beliefs. persecution sometimes follows. Current views on the importance and relevance of religious freedom as a human right are varied and complex, however what can be agreed upon is that persecution is never the right course of action, regardless of the reason. Cover image: Original iron cross from the grave of St. Mary MacKillop 1909, late-19th century, iron and timber. Australian Catholic University Art Collection Overleaf: John Coburn, The First Day: The Spirit of of God brooded over the waters, 1977. -

A Poet's Fable

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. ) 1 ( A POET’S FABLE EARLY IN 1529 a London lawyer, Simon Fish, anonymously pub- lished a tract, addressed to Henry VIII, called A Supplication for the Beggars. The tract was modest in length but explosive in content: Fish wrote on behalf of the homeless, desperate English men and women, “needy, impotent, blind, lame and sick” who pleaded for spare change on the streets of every city and town in the realm.1 These wretches, “on whom scarcely for horror any eye dare look,” have become so numerous that private charity can no longer sus- tain them, and they are dying of hunger.2 Their plight, in Fish’s account, is directly linked to the pestiferous spread throughout the realm of beggars of a different kind: bishops, abbots, priors, deacons, archdeacons, suffragans, priests, monks, canons, friars, pardoners, and summoners. Simon Fish had already given a foretaste of his anticlerical senti- ments and his satirical gifts. In his first year as a law student at Gray’s Inn, according to John Foxe, one of Fish’s mates, a certain Mr. Roo, had written a play holding Cardinal Wolsey up to ridicule. No one dared to take on the part of Wolsey until Simon Fish came forward and offered to do so. The performance must have been impressive: it so enraged the cardinal that Fish was forced “the same night that this Tragedy was played” to flee to the Low Coun- tries to escape arrest.3 There he evidently met the exile William Tyndale, whose new English translation of the Bible, inspired by Luther, he subsequently helped to circulate. -

Understanding Anti-Muslim Hate Crimes Addressing the Security Needs of Muslim Communities

Understanding Anti-Muslim Hate Crimes Addressing the Security Needs of Muslim Communities A Practical Guide Understanding Anti-Muslim Hate Crimes Addressing the Security Needs of Muslim Communities A Practical Guide Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul. Miodowa 10 00-251 Warsaw Poland www.osce.org/odihr © OSCE/ODIHR 2020 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the OSCE/ ODIHR as the source. ISBN 978-83-66089-93-8 Designed by Homework Printed in Poland by Centrum Poligrafii Contents Foreword v Executive Summary vii Introduction 1 PART ONE: Understanding the challenge 7 I. Hate crimes against Muslims in the OSCE region: context 8 II. Hate crimes against Muslims in the OSCE region: key features 12 III. Hate crimes against Muslims in the OSCE region: impact 21 PART TWO: International standards on intolerance against Muslims 29 I. Commitments and other international obligations 30 II. Key principles 37 1. Rights based 37 2. Victim focused 38 3. Non-discriminatory 41 4. Participatory 41 5. Shared 42 6. Collaborative 43 7. Empathetic 43 8. Gender sensitive 43 9. Transparent 44 10. Holistic 45 PART THREE: Responding to anti-Muslim hate crimes and the security challenges of Muslim communities 47 Practical steps 48 1. Acknowledging the problem 48 2. Raising awareness 51 3. Recognizing and recording the anti-Muslim bias motivation of hate crimes 53 4. Providing evidence of the security needs of Muslim communities by working with them to collect hate crime data 58 5. -

M.A. /M.Sc. in Criminology & Police Studies Syllabus

SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY OF POLICE, SECURITY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE JODHPUR, RAJASTHAN, INDIA M.A. /M.Sc. in Criminology & Police Studies SYLLABUS From the Academic Year 2017 - 2018 Onwards 1 SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY OF POLICE, SECURITY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE, JODHPUR, RAJASTHAN, INDIA M.A. /M. Sc. in Criminology and Police Studies From the academic year 2017 - 2018 onwards Scheme, Regulations and Syllabus Title of the course M.A/M.Sc in Criminology and Police Studies Duration of the course Two Years under Semester Pattern. Eligibility Graduate in any discipline with minimum 55% marks. (5% relaxation for SC/ST/PH candidates) Total Credit Points: 105 Structure of the programme This Master’s programme will consist of: a. Compulsory Papers and Elective Papers; I Semester: (22 Credits) 4 Compulsory Papers, 1 Elective Paper & 1 Practical Paper II Semester: (27 Credits) 4 Compulsory Papers, 1 Elective Paper & 2 Practical Papers (1 of them elective), Winter Internship (to be commenced at the ending of I semester and finished at beginning of II Semester) III Semester: (32 Credits) 4 Compulsory Papers, 1 Elective Paper, 1 Practical Paper & Summer Internship (to be commenced at the ending of II semester and finished at beginning of III Semester) Theory Papers: Each theory paper comprises 4 Contact hours / week. 4 Contact Hours = 2 Lectures+ 1 Tutorial+ 1 Seminar 2 • Electives: Electives will be offered only if a minimum of 5 students opt for that paper. • Practical Paper : The Subject called ‘Practical Paper’ may include any of the/some of the following activities such as Institutional field visits(for practical) & debate on particular issues or article writing on particular issues related to the subject / subject related discussion on short-films/ field based case-study etc. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture. -

Regional Implications of Shi'a Revival in Iraq

Vali Nasr Regional Implications of Shi‘a Revival in Iraq Since regime change disenfranchised the Sunni minority leader- ship that had ruled Iraq since the country’s independence in 1932 and em- powered the Shi‘a majority, the Shi‘a-Sunni competition for power has emerged as the single greatest determinant of peace and stability in post-Saddam Iraq. Iraq’s sectarian pains are all the more complex because reverberations of Shi‘a empowerment will inevitably extend beyond Iraq’s borders, involv- ing the broader region from Lebanon to Pakistan. The change in the sectar- ian balance of power is likely to have a far more immediate and powerful impact on politics in the greater Middle East than any potential example of a moderate and progressive government in Baghdad. The change in the sec- tarian balance of power will shape public perception of U.S. policies in Iraq as well as the long-standing balance of power between the Shi‘a and Sunnis that sets the foundation of politics from Lebanon to Pakistan. U.S. interests in the greater Middle East are now closely tied to the risks and opportunities that will emanate from the Shi‘a revival in Iraq. The competition for power between the Shi‘a and Sunnis is neither a new development nor one limited to Iraq. In fact, it has shaped alliances and de- termined how various actors have defined and pursued their interests in the region for the past three decades. Often overlooked in political analyses of greater Middle Eastern politics, this competition is key to grasping how cur- rent developments in Iraq will shape this region in years to come.