Fractures (Non-Complex): Assessment and Management Fractures: Diagnosis, Management and Follow-Up of Fractures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

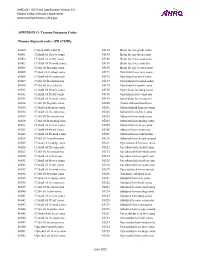

PSI Appendix G Version 6.0 Patient Safety Indicators Appendices

AHRQ QI™ ICD-9-CM Specification Version 6.0 Patient Safety Indicators Appendices www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov APPENDIX G: Trauma Diagnosis Codes Trauma diagnosis codes: (TRAUMID) 80000 Closed skull vault fx 85184 Brain lac nec-proln coma 80001 Cl skull vlt fx w/o coma 85185 Brain lac nec-deep coma 80002 Cl skull vlt fx-brf coma 85186 Brain lacer nec-coma nos 80003 Cl skull vlt fx-mod coma 85189 Brain lacer nec-concuss 80004 Cl skl vlt fx-proln coma 85190 Brain lac nec w open wnd 80005 Cl skul vlt fx-deep coma 85191 Opn brain lacer w/o coma 80006 Cl skull vlt fx-coma nos 85192 Opn brain lac-brief coma 80009 Cl skl vlt fx-concus nos 85193 Opn brain lacer-mod coma 80010 Cl skl vlt fx/cerebr lac 85194 Opn brain lac-proln coma 80011 Cl skull vlt fx w/o coma 85195 Open brain lac-deep coma 80012 Cl skull vlt fx-brf coma 85196 Opn brain lacer-coma nos 80013 Cl skull vlt fx-mod coma 85199 Open brain lacer-concuss 80014 Cl skl vlt fx-proln coma 85200 Traum subarachnoid hem 80015 Cl skul vlt fx-deep coma 85201 Subarachnoid hem-no coma 80016 Cl skull vlt fx-coma nos 85202 Subarach hem-brief coma 80019 Cl skl vlt fx-concus nos 85203 Subarach hem-mod coma 80020 Cl skl vlt fx/mening hem 85204 Subarach hem-prolng coma 80021 Cl skull vlt fx w/o coma 85205 Subarach hem-deep coma 80022 Cl skull vlt fx-brf coma 85206 Subarach hem-coma nos 80023 Cl skull vlt fx-mod coma 85209 Subarach hem-concussion 80024 Cl skl vlt fx-proln coma 85210 Subarach hem w opn wound 80025 Cl skul vlt fx-deep coma 85211 Opn subarach hem-no coma 80026 Cl skull vlt fx-coma nos 85212 -

Management of Pediatric Forearm Torus Fractures: a Systematic

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Management of Pediatric Forearm Torus Fractures A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Nan Jiang, MD,*† Zhen-hua Cao, MD,*‡ Yun-fei Ma, MD,*† Zhen Lin, MD,§ and Bin Yu, MD*† many disadvantages, such as heavy, bulky, and requires a second Objectives: Pediatric forearm torus fracture, a frequent reason for emer- visit to the hospital for removal. These flaws of cast may bring gency department visits, can be immobilized by both rigid cast and non- inconvenience to children as well as their families. In recent years, rigid methods. However, controversy still exists regarding the optimal many pediatric clinicians reported other methods to instead tradi- treatment of the disease. The aim of this study was to compare, in a system- tionally used cast, including soft cast,9,10 Futuro wrist splint,8,11 atic review, clinical efficacy of rigid cast with nonrigid methods for immo- and double Tubigrip.11 Although patients that suffered from fore- bilization of the pediatric forearm torus fractures. arm torus fractures can be immobilized by both rigid cast and non- Methods: Literature search was performed of PubMed and Cochrane Li- rigid materials, controversy still exists in the optimal treatment of brary by 2 independent reviewers to identify randomized controlled trials this fracture. comparing rigid cast with nonrigid methods for pediatric forearm torus The aim of this study was to, in a systematic review and fractures from inception to December 31, 2013, without limitation of publi- meta-analysis, compare clinical efficacy of recently used nonrigid cation language. Trial quality was assessed using the modified Jadad scale. immobilization methods with rigid cast. -

Vanderbilt Sports Medicine

Alabama AAP Fall Meeting Sept.19-20, 2009 Pediatric Fracture Care for the Pediatrician Andrew Gregory, MD, FAAP, FACSM Assistant Professor Orthopedics & Pediatrics Program Director, Sports Medicine Fellowship Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt Sports Medicine Disclosure No conflict of interest - unfortunately for me, I have no financial relationships with companies making products regarding this topic to disclose Objectives Review briefly the differences of pediatric bone Review Pediatric Fracture Classification Discuss subtle fractures in kids Discuss a few other pediatric only conditions 1 Pediatric Skeleton Bone is relatively elastic and rubbery Periosteum is quite thick & active Ligaments are strong relative to the bone Presence of the physis - “weak link” Ligament injuries & dislocations are rare – “kids don’t sprain stuff” Fractures heal quickly and have the capacity to remodel Anatomy of Pediatric Bone Epiphysis Physis Metaphysis Diaphysis Apophysis Pediatric Fracture Classification Plastic Deformation – Bowing usually of fibula or ulna Buckle/ Torus – compression, stable Greenstick – unicortical tension Complete – Spiral, Oblique, Transverse Physeal – Salter-Harris Apophyseal avulsion 2 Plastic deformation Bowing without fracture Often deformed requiring reduction Buckle (Torus) Fracture Buckled Periosteum – Metaphyseal/ diaphyseal junction Greenstick Fracture Cortex Broken on Only One Side – Incomplete 3 Complete Fractures Transverse – Perpendicular to the bone Oblique – Across the bone at 45-60 o – Unstable Spiral – Rotational -

Pediatric Orthopedic Injuries… … from an ED State of Mind

Traumatic Orthopedics Peds RC Exam Review February 28, 2019 Dr. Naminder Sandhu, FRCPC Pediatric Emergency Medicine Objectives to cover today • Normal bone growth and function • Common radiographic abnormalities in MSK diseases • Part 1: Atraumatic – Congenital abnormalities – Joint and limb pain – Joint deformities – MSK infections – Bone tumors – Common gait disorders • Part 2: Traumatic – Common pediatric fractures and soft tissue injuries by site Overview of traumatic MSK pain Acute injuries • Fractures • Joint dislocations – Most common in ED: patella, digits, shoulder, elbow • Muscle strains – Eg. groin/adductors • Ligament sprains – Eg. Ankle, ACL/MCL, acromioclavicular joint separation Chronic/ overuse injuries • Stress fractures • Tendonitis • Bursitis • Fasciitis • Apophysitis Overuse injuries in the athlete WHY do they happen?? Extrinsic factors: • Errors in training • Inappropriate footwear Overuse injuries Intrinsic: • Poor conditioning – increased injuries early in season • Muscle imbalances – Weak muscle near strong (vastus medialus vs lateralus patellofemoral pain) – Excessive tightness: IT band, gastroc/soleus Sever disease • Anatomic misalignments – eg. pes planus, genu valgum or varum • Growth – strength and flexibility imbalances • Nutrition – eg. female athlete triad Misalignment – an intrinsic factor Apophysitis • *Apophysis = natural protruberance from a bone (2ndary ossification centres, often where tendons attach) • Examples – Sever disease (Calcaneal) – Osgood Schlatter disease (Tibial tubercle) – Sinding-Larsen-Johansson -

Torus (Buckle) Fracture Discharge Advice

Torus (Buckle) Fracture Discharge Advice Information for you Follow us on Twitter @NHSaaa Find us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/nhsaaa Visit our website: www.nhsaaa.net All our publications are available in other formats What has happened? Your child has sustained a torus fracture, also known as a “buckle” fracture, of the radius and/or ulna (the long bones at the wrist). The bone “buckles” on one side rather than actually breaks and is commonly seen in children as their bones are soft and flexible. Will my child need a cast? Torus fractures heal well without any long-term complications. They do not require any operations or to be placed in a cast. However, using a wrist splint provides comfort and reduces the risk of further injury. It should be worn at all times but can be removed for washing and showering without any risk to the fracture. Simple painkillers such as paracetamol and/or ibuprofen can also be used to reduce discomfort. How long should my child wear the splint for? In general, the older the child is, the longer they will need to wear the splint. We recommend that children under five years old should wear the splint for one week, those age five to ten years should wear it for two weeks and those over ten years should wear it for three weeks. If your child removes the splint before this time but is comfortable and moving their wrist freely then there is no need to insist that they wear the splint for longer. However, if your child is still sore and reluctant to use their wrist when the splint is removed, then you 2 may reapply the splint. -

Musculoskeletal System Imaging

SUMPh “N. Testemitanu” Radiology and Medical imaging department MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM IMAGING M. Crivceanschii, assistant professor GOALS AND OBJECTIVES • to be aware of the role of modern diagnostic imaging modalities • to be familiar with main radiological signs and syndromes • tips and tricks in musculoskeletal imaging IMAGING MODALITIES • that every student should now IMAGING MODALITIES • Conventional Radiography • Fluoroscopy • Arthrography • Computed Tomography • Magnetic Resonance Imaging • Ultrasound • Scintigraphy PLAIN X-RAY FILM • First line study for most medical issues • Excellent for fractures/bony detail • Very limited for soft tissues (ligaments, tendons, muscles) • Only a screening tool in the spine • The radiologist should obtain at least two (2) views of the bone involved at 90° angles to each other • with each view including two adjacent joints FLUOROSCOPY • Arthrography • Tenography • Arteriography • Percutaneous Bone or Soft Tissue Biopsy CT SCANNING • Excellent for bony structural anatomy in the setting of complicated fracture • Less effective than MR for soft tissues and active processes • High radiation Dose • Interventional options MRI SCANNING • Excellent for soft tissue pathology • Good-excellent for bone pathology • No ionizing radiation • NOT patient friendly • Some absolute and relative contraindications ULTRASOUND • Reproducible in trained hands • Excellent for superficial soft tissue elements including tendons and muscles • No ionizing radiation • Patient friendly SCINTIGRAPHY • Image the entire skeleton at once • It provides a metabolic picture • It is particularly helpful in condition such as fibrous dysplasia, Langerhans Cell Histocytosis or metastatic cancer. CONGENITAL SKELETAL ANOMALIES CONGENITAL SKELETAL ANOMALIES • Chromosomal disorders (e. g. Down’s syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Turner’s syndrome, etc.) • Dwarfism (rhizomelic – proximal segments shortening, mesomelic – middle segments, acromelic – distal segments) • Skeletal dysplasias (e. -

Musculoskeletal Radiograph Interpretation – Specific Approach by Joint/Area

Musculoskeletal Radiograph Interpretation – Specific Approach by Joint/Area The generic approach to musculoskeletal radiograph interpretation is covered separately. This is sufficient for most single bone radiographs. However, radiographs of many joints/areas require a specific approach to interpretation or have specific signs which need to be looked for within the ABCS approach – these are outlined here. Facial bones Identify zygoma (stool) and look for fractures of its 4 legs: 1. Zygomatic arch – if you imagine the zygoma as an elephant’s head, this leg looks like an its trunk on a radiograph 2. Frontal process of zygoma 3. Orbital floor 4. Lateral wall of maxillary antrum Soft tissue signs indicating a fracture (working downwards) o Black eyebrow sign – black eyebrow like shadow across top of orbit (air in orbit 2 from sinus, usually due to orbital blow-out fracture) 1 3 o MAXILLARY 1 Teardrop sign – dark shadow at the top of the maxillary antrum (soft tissue ANTRUM herniation of orbital contents from orbital blow-out fracture) 4 o Fluid level – in maxillary antrum (blood from fracture) Common pathology Nasal bone fracture: commonly due to punch injury; may not be seen on radiographs and X-rays are not performed to specifically look for it as it does not change management; look up the patient’s nose to exclude a septal haematoma! Mandible fracture: commonly due to punch injury; use an OPG X-ray to look for it, not a facial bone X-ray Zygomatic arch fracture Orbital floor fracture ‘Tripod’ fracture: fractures of all 4 ‘legs’ of the zygoma due to major trauma – should really be called a quadripod fracture Cervical spine Lateral view (ABCS)… Adequacy: Need to see skull base and C7/T1 disc space (if not, get swimmer’s view) Alignment Alignment arcs (look for smooth curves) 1. -

Medicare Cost of Osteoporotic Fractures: Supplement the Clinical and Cost Burden of an Important Consequence of Osteoporosis

MILLIMAN RESEARCH REPORT Medicare cost of osteoporotic fractures: Supplement The clinical and cost burden of an important consequence of osteoporosis August 2019 Dane Hansen, FSA, MAAA Carol Bazell, MD, MPH Pamela Pelizzari, MPH Bruce Pyenson, FSA, MAAA Commissioned by the National Osteoporosis Foundation MILLIMAN RESEARCH REPORT Table of Contents APPENDIX C: CODE SETS .......................................................................................................................................... 2 C-1. QUALIFIED CLAIMS ......................................................................................................................................... 2 C-2. CANCER DIAGNOSIS CODES ......................................................................................................................... 2 C-3. FRACTURE DIAGNOSIS CODES .................................................................................................................. 32 C-4. HIGH IMPACT DIAGNOSIS CODES .............................................................................................................. 58 C-5. OSTEOPOROSIS DIAGNOSIS CODES ......................................................................................................... 59 C-6. CMS HIERARCHICAL CONDITION CATEGORIES (CMS-HCC) ................................................................... 59 C-7. BONE MINERAL DENSITY (BMD) TEST SERVICE CODES ......................................................................... 60 C-8. NURSING FACILITY EVALUATION & MANAGEMENT -

Ouch, That's Gotta Hurt! Pediatric Fractures & Injuries

Ouch, That’s Gotta Hurt! Pediatric Fractures & Injuries Greg Canty, MD Medical Director, Sports Medicine Center Attending Physician, Emergency Medicine Children’s Mercy Kansas City © 2011 Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics. All Rights Reserved. • June 2011 Disclosures • I have no relevant financial relationships with the manufacturer(s) of any commercial product(s) and/or provider of commercial services discussed in this CME activity • I do not intend to discuss any unapproved/investigative use of a commercial product/device in my presentation 2 ©2013 Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics. All Rights Reserved. 03/13 The Game Plan • Review the unique features of pediatric bone • Understand how to best assess suspected fractures in the urgent care • Implement the latest evidence for acute management of fractures and injuries 3 ©2013 Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics. All Rights Reserved. 03/13 Fractures in Pediatrics ? • 1/3 of patients will have a fracture before age 17 • 42% boys & 27% girls • 10‐15% of all childhood injuries involve a fracture • Most common – Distal forearm – Clavicle – Fingers – Ankle 4 ©2013 Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics. All Rights Reserved. 03/13 The Pediatric Skeleton • Bone porous and flexible…unique fractures • Periosteum is very thick & active • Ligaments are strong relative to the bone • Presence of the physis ‐ “weak link” • Ligament injuries & dislocations are less common – “kids don’t sprain” • Fractures heal quickly and have the capacity to remodel 5 ©2013 Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics. All Rights Reserved. 03/13 Anatomy of Pediatric Bone • Epiphysis • Physis • Metaphysis • Diaphysis • Apophysis 6 ©2013 Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics. -

Basic Principles in the Assessment and Treatment of Fractures in Skeletally Immature Patients

Basic Principles in the Assessment and Treatment of Fractures in Skeletally Immature Patients Joshua Klatt, MD Original Author: Steven Frick, MD; March 2004 1st Revision: Steven Frick, MD; August 2006 2nd Revision: Joshua Klatt, MD; December 2010 Anatomy Unique to Skeletally Immature Bones • Anatomy – Epiphysis – Physis – Metaphysis – Diaphysis • Physis = growth plate Anatomy Unique to Skeletally Immature Bones • Periosteum – Thicker – More osteogenic – Attached firmly at periphery of physes • Bone – More porous – More ductile Periosteum • Osteogenic • More readily elevated from diaphysis and metaphysis than in adults • Often intact on the concave (compression) side of the injury – Often helpful as a hinge for reduction – Promotes rapid healing • Periosteal new bone contributes to remodeling From: The Closed Treatment of Fractures, John Charley Physeal Anatomy • Gross - secondary centers of ossification • Histologic zones • Vascular anatomy Centers of Ossification • 1° ossification center – Diaphyseal • 2° ossification centers – Epiphyseal – Occur at different stages of development – Usually occurs earlier in girls than boys source: http://training.seer.cancer.gov Physeal Anatomy • Reserve zone – Matrix production Epiphyseal side • Proliferative zone – Cellular proliferation – Longitudinal growth • Hypertrophic zone – subdivided into Metaphyseal side • Maturation • Degeneration • Provisional calcification With permission from M. Ghert, MD McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario Examination of the Injured Child • Assess location of deformity -

Evaluating Common Fractures

Evaluation of Common Fractures Vinitha Shenava, MD Orthopedics Objectives • Characteristics of pediatric bone and fractures • Treatment, evaluation, and management of fractures • Recognize patterns associated with child abuse Key Points 1. Obtain at least 2 view X-rays of the area of concern 2. Manage select fractures in your office • Birth injuries • Buckle fx • Toddler fx • Clavicle fx • Proximal humerus fx • Fibula fractures 3. Refer physeal fractures and fractures needing surgery to pediatric orthopedics Facts • Fracture rates increasing – Sports – Obesity • Male predominance – 40% of boys and 25% of girls will sustain a fracture by 16 • 15-30% involve the growth plate Properties of an Immature Bone • More porous • More flexible • Thicker periosteum (lining around the bone) • Growth plate (physis) is present • Leads to unique fracture patterns Fractures Unique to Children • Buckle fractures • Plastic deformation • Greenstick fractures • Physeal fractures Physis • The physis is made of cartilage • Responsible for longitudinal growth • Area of relative weakness Classification of Physeal Injuries: Salter Harris Physis is Our Friend When the bone is angulated, the physis will guide growth so that the physis will become parallel REMODELING The Physis is Our Friend 4 + 8 4 + 9 5 + 0 5 + 10 • Process is more robust in younger patients • Remodeling is faster closer to the physis The Physis can be our FOE • Damage to the physis can be irreversible • Resulting in progressive deformity History Mechanism of injury? • Home • Sport • MVA • Unknown? -

Diagnosis Code Hospital Acquired Conditions, Trauma Code Descriptions CC/MCC 80000 Closed Fracture of Vault of Skull Without

Diagnosis Hospital Acquired Conditions, Trauma Code Descriptions CC/MCC code 80000 Closed fracture of vault of skull without mention of intracranial injury, with CC state of consciousness unspecified 80001 Closed fracture of vault of skull without mention of intracranial injury, with CC no loss of consciousness 80002 Closed fracture of vault of skull without mention of intracranial injury, with CC brief (less than one hour) loss of consciousness 80003 Closed fracture of vault of skull without mention of intracranial injury, with MajorCC moderate (1-24 hours) loss of consciousness 80004 Closed fracture of vault of skull without mention of intracranial injury, with MajorCC prolonged (more than 24 hours) loss of consciousness and return to pre- existing conscious level 80005 Closed fracture of vault of skull without mention of intracranial injury, with MajorCC prolonged (more than 24 hours) loss of consciousness, without return to pre-existing conscious level 80006 Closed fracture of vault of skull without mention of intra cranial injury, CC with loss of consciousness of unspecified duration 80009 Closed fracture of vault of skull without mention of intracranial injury, with CC concussion, unspecified 80010 Closed fracture of vault of skull with cerebral laceration and contusion, MajorCC with state of consciousness unspecified 80011 Closed fracture of vault of skull with cerebral laceration and contusion, MajorCC with no loss of consciousness 80012 Closed fracture of vault of skull with cerebral laceration and contusion, MajorCC with brief