Skeletal Atlas of Child Abuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saving Smiles Avulsion Pathway (Page 20) Saving Smiles: Fractures and Displacements (Page 22)

Greater Manchester Local Dental Network SavingSmiles Improving outcomes following dental trauma First Edition I Spring 2017 Practitioners’ Toolkit Contents 04 Introduction to the toolkit from the GM Trauma Network 06 History & examination 10 Maxillo-facial considerations 12 Classification of dento-alveolar injuries 16 The paediatric patient 18 Splinting 20 The AVULSED Tooth 22 The BROKEN Tooth 23 Managing injuries with delayed presentation SavingSmiles 24 Follow up Improving outcomes 26 Long term consequences following dental trauma 28 Armamentarium 29 When to refer 30 Non-accidental injury 31 What should I do if I suspect dental neglect or abuse? 34 www.dentaltrauma.co.uk 35 Additional reference material 36 Dental trauma history sheet 38 Avulsion pathways 39 Fractues and displacement pathway 40 Fractures and displacements in the primary dentition 41 Acknowledgements SavingSmiles Improving outcomes following dental trauma Ambition for Greater Manchester Introduction to the Toolkit from The GM Trauma Network wish to work with our colleagues to ensure that: the GM Trauma Network • All clinicians in GM have the confidence and knowledge to provide a timely and effective first line response to dental trauma. • All clinicians are aware of the need for close monitoring of patients following trauma, and when to refer. The Greater Manchester Local Dental Network (GM LDN) has established a ‘Trauma Network’ sub-group. The • All settings have the equipment described within the ‘armamentarium’ section of this booklet to support optimal treatment. Trauma Network was established to support a safer, faster, better first response to dental trauma and follow up care across GM. The group includes members representing general dental practitioners, commissioners, To support GM practitioners in achieving this ambition, we will be working with Health Education England to provide training days and specialists in restorative and paediatric dentistry, and dental public health. -

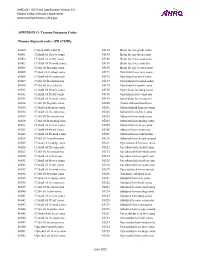

PSI Appendix G Version 6.0 Patient Safety Indicators Appendices

AHRQ QI™ ICD-9-CM Specification Version 6.0 Patient Safety Indicators Appendices www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov APPENDIX G: Trauma Diagnosis Codes Trauma diagnosis codes: (TRAUMID) 80000 Closed skull vault fx 85184 Brain lac nec-proln coma 80001 Cl skull vlt fx w/o coma 85185 Brain lac nec-deep coma 80002 Cl skull vlt fx-brf coma 85186 Brain lacer nec-coma nos 80003 Cl skull vlt fx-mod coma 85189 Brain lacer nec-concuss 80004 Cl skl vlt fx-proln coma 85190 Brain lac nec w open wnd 80005 Cl skul vlt fx-deep coma 85191 Opn brain lacer w/o coma 80006 Cl skull vlt fx-coma nos 85192 Opn brain lac-brief coma 80009 Cl skl vlt fx-concus nos 85193 Opn brain lacer-mod coma 80010 Cl skl vlt fx/cerebr lac 85194 Opn brain lac-proln coma 80011 Cl skull vlt fx w/o coma 85195 Open brain lac-deep coma 80012 Cl skull vlt fx-brf coma 85196 Opn brain lacer-coma nos 80013 Cl skull vlt fx-mod coma 85199 Open brain lacer-concuss 80014 Cl skl vlt fx-proln coma 85200 Traum subarachnoid hem 80015 Cl skul vlt fx-deep coma 85201 Subarachnoid hem-no coma 80016 Cl skull vlt fx-coma nos 85202 Subarach hem-brief coma 80019 Cl skl vlt fx-concus nos 85203 Subarach hem-mod coma 80020 Cl skl vlt fx/mening hem 85204 Subarach hem-prolng coma 80021 Cl skull vlt fx w/o coma 85205 Subarach hem-deep coma 80022 Cl skull vlt fx-brf coma 85206 Subarach hem-coma nos 80023 Cl skull vlt fx-mod coma 85209 Subarach hem-concussion 80024 Cl skl vlt fx-proln coma 85210 Subarach hem w opn wound 80025 Cl skul vlt fx-deep coma 85211 Opn subarach hem-no coma 80026 Cl skull vlt fx-coma nos 85212 -

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Root Resorption After Dental Trauma: a Systematic Scoping Review Kerstin M

Galler et al. BMC Oral Health (2021) 21:163 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01510-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Pathophysiological mechanisms of root resorption after dental trauma: a systematic scoping review Kerstin M. Galler1*, Eva‑Maria Grätz1, Matthias Widbiller1 , Wolfgang Buchalla1 and Helge Knüttel2 Abstract Background: The objective of this scoping review was to systematically explore the current knowledge of cellular and molecular processes that drive and control trauma‑associated root resorption, to identify research gaps and to provide a basis for improved prevention and therapy. Methods: Four major bibliographic databases were searched according to the research question up to Febru‑ ary 2021 and supplemented manually. Reports on physiologic, histologic, anatomic and clinical aspects of root resorption following dental trauma were included. Duplicates were removed, the collected material was screened by title/abstract and assessed for eligibility based on the full text. Relevant aspects were extracted, organized and summarized. Results: 846 papers were identifed as relevant for a qualitative summary. Consideration of pathophysiological mechanisms concerning trauma‑related root resorption in the literature is sparse. Whereas some forms of resorption have been explored thoroughly, the etiology of others, particularly invasive cervical resorption, is still under debate, resulting in inadequate diagnostics and heterogeneous clinical recommendations. Efective therapies for progres‑ sive replacement resorptions have not been established. Whereas the discovery of the RANKL/RANK/OPG system is essential to our understanding of resorptive processes, many questions regarding the functional regulation of osteo‑/ odontoclasts remain unanswered. Conclusions: This scoping review provides an overview of existing evidence, but also identifes knowledge gaps that need to be addressed by continued laboratory and clinical research. -

Management of Pediatric Forearm Torus Fractures: a Systematic

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Management of Pediatric Forearm Torus Fractures A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Nan Jiang, MD,*† Zhen-hua Cao, MD,*‡ Yun-fei Ma, MD,*† Zhen Lin, MD,§ and Bin Yu, MD*† many disadvantages, such as heavy, bulky, and requires a second Objectives: Pediatric forearm torus fracture, a frequent reason for emer- visit to the hospital for removal. These flaws of cast may bring gency department visits, can be immobilized by both rigid cast and non- inconvenience to children as well as their families. In recent years, rigid methods. However, controversy still exists regarding the optimal many pediatric clinicians reported other methods to instead tradi- treatment of the disease. The aim of this study was to compare, in a system- tionally used cast, including soft cast,9,10 Futuro wrist splint,8,11 atic review, clinical efficacy of rigid cast with nonrigid methods for immo- and double Tubigrip.11 Although patients that suffered from fore- bilization of the pediatric forearm torus fractures. arm torus fractures can be immobilized by both rigid cast and non- Methods: Literature search was performed of PubMed and Cochrane Li- rigid materials, controversy still exists in the optimal treatment of brary by 2 independent reviewers to identify randomized controlled trials this fracture. comparing rigid cast with nonrigid methods for pediatric forearm torus The aim of this study was to, in a systematic review and fractures from inception to December 31, 2013, without limitation of publi- meta-analysis, compare clinical efficacy of recently used nonrigid cation language. Trial quality was assessed using the modified Jadad scale. immobilization methods with rigid cast. -

Vanderbilt Sports Medicine

Alabama AAP Fall Meeting Sept.19-20, 2009 Pediatric Fracture Care for the Pediatrician Andrew Gregory, MD, FAAP, FACSM Assistant Professor Orthopedics & Pediatrics Program Director, Sports Medicine Fellowship Vanderbilt University Vanderbilt Sports Medicine Disclosure No conflict of interest - unfortunately for me, I have no financial relationships with companies making products regarding this topic to disclose Objectives Review briefly the differences of pediatric bone Review Pediatric Fracture Classification Discuss subtle fractures in kids Discuss a few other pediatric only conditions 1 Pediatric Skeleton Bone is relatively elastic and rubbery Periosteum is quite thick & active Ligaments are strong relative to the bone Presence of the physis - “weak link” Ligament injuries & dislocations are rare – “kids don’t sprain stuff” Fractures heal quickly and have the capacity to remodel Anatomy of Pediatric Bone Epiphysis Physis Metaphysis Diaphysis Apophysis Pediatric Fracture Classification Plastic Deformation – Bowing usually of fibula or ulna Buckle/ Torus – compression, stable Greenstick – unicortical tension Complete – Spiral, Oblique, Transverse Physeal – Salter-Harris Apophyseal avulsion 2 Plastic deformation Bowing without fracture Often deformed requiring reduction Buckle (Torus) Fracture Buckled Periosteum – Metaphyseal/ diaphyseal junction Greenstick Fracture Cortex Broken on Only One Side – Incomplete 3 Complete Fractures Transverse – Perpendicular to the bone Oblique – Across the bone at 45-60 o – Unstable Spiral – Rotational -

Pediatric Orthopedic Injuries… … from an ED State of Mind

Traumatic Orthopedics Peds RC Exam Review February 28, 2019 Dr. Naminder Sandhu, FRCPC Pediatric Emergency Medicine Objectives to cover today • Normal bone growth and function • Common radiographic abnormalities in MSK diseases • Part 1: Atraumatic – Congenital abnormalities – Joint and limb pain – Joint deformities – MSK infections – Bone tumors – Common gait disorders • Part 2: Traumatic – Common pediatric fractures and soft tissue injuries by site Overview of traumatic MSK pain Acute injuries • Fractures • Joint dislocations – Most common in ED: patella, digits, shoulder, elbow • Muscle strains – Eg. groin/adductors • Ligament sprains – Eg. Ankle, ACL/MCL, acromioclavicular joint separation Chronic/ overuse injuries • Stress fractures • Tendonitis • Bursitis • Fasciitis • Apophysitis Overuse injuries in the athlete WHY do they happen?? Extrinsic factors: • Errors in training • Inappropriate footwear Overuse injuries Intrinsic: • Poor conditioning – increased injuries early in season • Muscle imbalances – Weak muscle near strong (vastus medialus vs lateralus patellofemoral pain) – Excessive tightness: IT band, gastroc/soleus Sever disease • Anatomic misalignments – eg. pes planus, genu valgum or varum • Growth – strength and flexibility imbalances • Nutrition – eg. female athlete triad Misalignment – an intrinsic factor Apophysitis • *Apophysis = natural protruberance from a bone (2ndary ossification centres, often where tendons attach) • Examples – Sever disease (Calcaneal) – Osgood Schlatter disease (Tibial tubercle) – Sinding-Larsen-Johansson -

Guideline on Management of Acute Dental Trauma

rEfErence manual v 32 / No 6 10 / 11 Guideline on Management of Acute Dental Trauma Originating Council Council on Clinical Affairs Review Council Council on Clinical Affairs Adopted 2001 Revised 2004, 2007, 2010 Purpose violence, and sports.7-10 All sporting activities have an asso- The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) ciated risk of orofacial injuries due to falls, collisions, and intends these guidelines to define, describe appearances, and contact with hard surfaces.11 The AAPD encourages the use set forth objectives for general management of acute trau- of protective gear, including mouthguards, which help dis- matic dental injuries rather than recommend specific treat- tribute forces of impact, thereby reducing the risk of severe ment procedures that have been presented in considerably injury.13,14 more detail in text-books and the dental/medical literature. Dental injuries could have improved outcomes if the public were aware of first-aid measures and the need to seek Methods immediate treatment.14-17 Because optimal treatment results This guideline is an update of the previous document re- follow immediate assessment and care,18 dentists have an vised in 2007. It is based on a review of the current dental ethical obligation to ensure that reasonable arrangements and medical literature related to dental trauma. An elec- for emergency dental care are available.19 The history, cir- tronic search was conducted using the following parameters: cumstances of the injury, pattern of trauma, and behavior Terms: “teeth”, “trauma”, “permanent teeth”, and “primary of the child and/or caregiver are important in distin- teeth”; Field: all fields; Limits: within the last 10 years; guishing nonabusive injuries from abuse.20 humans; English. -

Pediatric Orbital Fractures

Review Article 9 Pediatric Orbital Fractures Adam J. Oppenheimer, MD1 Laura A. Monson, MD1 Steven R. Buchman, MD1 1 Section of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Address for correspondence and reprint requests Steven R. Buchman, Michigan Hospitals, Ann Arbor, Michigan MD, Section of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan Health System, 2130 Taubman Center, SPC 5340, Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstruction 2013;6:9–20 1500 E. Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-5340 (e-mail: [email protected]). Abstract It is wise to recall the dictum “children are not small adults” when managing pediatric Keywords orbital fractures. In a child, the craniofacial skeleton undergoes significant changes in ► orbit size, shape, and proportion as it grows into maturity. Accordingly, the craniomaxillo- ► pediatric facial surgeon must select an appropriate treatment strategy that considers both the ► trauma nature of the injury and the child’s stage of growth. The following review will discuss the ► enophthalmos management of pediatric orbital fractures, with an emphasis on clinically oriented ► entrapment anatomy and development. Pediatric orbital fractures occur in discreet patterns, based on 12 years of age. During mixed dentition, the cuspid teeth are the characteristic developmental anatomy of the craniofacial immediately beneath the orbit: hence the term eye tooth in skeleton at the time of injury. To fully understand pediatric dental parlance. It is not until age 12 that the maxillary sinus orbital trauma, the craniomaxillofacial surgeon must first be expands, in concert with eruption of the permanent denti- aware of the anatomical and developmental changes that tion. At 16 years of age, the maxillary sinus reaches adult size occur in the pediatric skull. -

The Impact of Sport Training on Oral Health in Athletes

dentistry journal Review The Impact of Sport Training on Oral Health in Athletes Domenico Tripodi, Alessia Cosi, Domenico Fulco and Simonetta D’Ercole * Department of Medical, Oral and Biotechnological Sciences, University “G. D’Annunzio” of Chieti-Pescara, Via dei Vestini 31, 66100 Chieti, Italy; [email protected] (D.T.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (D.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Athletes’ oral health appears to be poor in numerous sport activities and different diseases can limit athletic skills, both during training and during competitions. Sport activities can be considered a risk factor, among athletes from different sports, for the onset of oral diseases, such as caries with an incidence between 15% and 70%, dental trauma 14–70%, dental erosion 36%, pericoronitis 5–39% and periodontal disease up to 15%. The numerous diseases are related to the variations that involve the ecological factors of the oral cavity such as salivary pH, flow rate, buffering capability, total bacterial count, cariogenic bacterial load and values of secretory Immunoglobulin A. The decrease in the production of S-IgA and the association with an important intraoral growth of pathogenic bacteria leads us to consider the training an “open window” for exposure to oral cavity diseases. Sports dentistry focuses attention on the prevention and treatment of oral pathologies and injuries. Oral health promotion strategies are needed in the sports environment. To prevent the onset of oral diseases, the sports dentist can recommend the use of a custom-made mouthguard, an oral device with a triple function that improves the health and performance of athletes. -

Sideline Emergency Management

Lecture 13 June 15, 2018 6/15/2018 Sideline Emergency Management Benjamin Oshlag, MD, CAQSM Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine Assistant Professor of Sports Medicine Columbia University Medical Center Disclosures Nothing to disclose ©AllinaHealthSystems 1 Lecture 13 June 15, 2018 31 New Orleans Criteria • Single center, 1429 patients from 1997-99 • CT needed if patient meets one of the following: –Headache –Vomiting –Age >60 –Drug or alcohol intoxication –Persistent anterograde amnesia –Visible trauma above the clavicle –Seizure • 6.5% of patients (93/1429) had intracranial injuries, 0.4% (6/1429) required neurosurgical intervention • 100% sensitive for intracranial injuries, 25% specific 32 Canadian Head CT Rule • Prospective cohort study at 10 sites in Canada (N=3121) (2001) • Apply only to: –GCS 13-15 –Amnesia or disorientation to the head injury event or +LOC –Injury within 24 hours •Exclusion –Age <16 –Oral anticoagulants –Seizure after injury –Minimal head injury (no LOC, disorientation, or amnesia) –Obvious skull injury/fracture –Acute neurologic deficit –Unstable vitals –Pregnant ©AllinaHealthSystems 16 Lecture 13 June 15, 2018 33 Canadian Head CT Rule • High Risk Criteria (need for NSG intervention) –GCS <15 at 2 hours post injury –Suspected open or depressed skull fracture –Any sign of basilar skull fracture > Hemotympanum, racoon eyes, Battle’s sign, CSF oto/rhinorrhea –>= 2 episodes of vomiting –Age >= 65 –100% sensitivity 34 Canadian Head CT Rule • Medium Risk Criteria (positive CT that usually requires admission) –Retrograde -

Torus (Buckle) Fracture Discharge Advice

Torus (Buckle) Fracture Discharge Advice Information for you Follow us on Twitter @NHSaaa Find us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/nhsaaa Visit our website: www.nhsaaa.net All our publications are available in other formats What has happened? Your child has sustained a torus fracture, also known as a “buckle” fracture, of the radius and/or ulna (the long bones at the wrist). The bone “buckles” on one side rather than actually breaks and is commonly seen in children as their bones are soft and flexible. Will my child need a cast? Torus fractures heal well without any long-term complications. They do not require any operations or to be placed in a cast. However, using a wrist splint provides comfort and reduces the risk of further injury. It should be worn at all times but can be removed for washing and showering without any risk to the fracture. Simple painkillers such as paracetamol and/or ibuprofen can also be used to reduce discomfort. How long should my child wear the splint for? In general, the older the child is, the longer they will need to wear the splint. We recommend that children under five years old should wear the splint for one week, those age five to ten years should wear it for two weeks and those over ten years should wear it for three weeks. If your child removes the splint before this time but is comfortable and moving their wrist freely then there is no need to insist that they wear the splint for longer. However, if your child is still sore and reluctant to use their wrist when the splint is removed, then you 2 may reapply the splint. -

PAMELA R.SINGLETARY, D.D.S. JEFFREY B. GREGERSON, D.M.D. TEXAS TOOTH FAIRIES PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY 3401 El SALIDO PKWY, CEDAR PARK TX 78613

PAMELA R.SINGLETARY, D.D.S. JEFFREY B. GREGERSON, D.M.D. TEXAS TOOTH FAIRIES PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY 3401 El SALIDO PKWY, CEDAR PARK TX 78613 Child’s Name ___________________________ Preferred Name ______________ Age _____ DOB _________Sex: F/M Child’s Physician __________________________________ Phone #_____________________________ Person accompanying child to appointment: ________________________________________________________ Preferred method of contact for appointment reminder notifications: Text Email Phone Call Has your home address/phone number/email changed? YES or NO (If YES, please fill out the following) Address/City/Zip: __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Home Phone : __________________________ Work: ___________________________ Cell# ______________________________ Email Address: ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Has your dental insurance changed? YES or NO (If YES, please fill out the following and/or allow us to see your card) Insured Name ___________________________________________________________ SSN/ID __________________________________ DOB _____________________________ Relationship to Child __________________________________________ Place of Employment _______________________________________________ Occupation ____________________________________ Work Phone# _____________________________ Name of Dental Carrier _________________________________________________________ Group# _____________________________