The French Technology of Nationalism in Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Stump, Morphotactics Lecture 2, 7-10-17.Pdf

7-6-17 Morphotactics 1 1. Canonical typology 2. Canonical inflection 3. Canonical morphotactics 7-6-17 Morphotactics 2 1. Canonical typology ✔ ︎ 2. Canonical inflection ✔ ︎ 3. Canonical morphotactics 7-10-17 Morphotactics 3 First off, what is morphotactics? The internal patterns according to which a language’s complex word forms are defined constitute its morphotactics. In the morpheme-based approaches to morphology that emerged in the twentieth century, a language’s morphotactic principles are constraints on the concatenation of morphemes (a perspective still held by many linguists). In rule-based conceptions of morphology, by contrast, a language’s morphotactic principles are constraints on the interaction of its rules of morphology in the definition of a word form. 7-10-17 Morphotactics 4 First off, what is morphotactics? The internal patterns according to which a language’s complex word forms are defined constitute its morphotactics. In the morpheme-based approaches to morphology that emerged in the twentieth century, a language’s morphotactic principles are constraints on the concatenation of morphemes (a perspective still held by many linguists). In rule-based conceptions of morphology, by contrast, a language’s morphotactic principles are constraints on the interaction of its rules of morphology in the definition of a word form. 7-10-17 Morphotactics 5 First off, what is morphotactics? The internal patterns according to which a language’s complex word forms are defined constitute its morphotactics. In the morpheme-based approaches to morphology that emerged in the twentieth century, a language’s morphotactic principles are constraints on the concatenation of morphemes (a perspective still held by many linguists). -

Gorée: Island of Memories

GOREE ISLAND OF MEMORIES GOREE ISLAND OF MEMORIES Unesco The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Unesco concerning the legal status of any country territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published in 1985 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7 place de Fontenoy, 75700 Paris Printed by L. Vanmelle, Ghent, Belgium ISBN 92-3-102348-9 French edition 92-3-202348-2 © Unesco 1985 Printed in Belgium PREFACE Scarely have the lights of Dakar dimmed on the horizon than the launch puts in at the little harbour of Gorée. Half an hour has passed, just long enough for the sea-breeze to smooth away, as if by magic, the lines of fatigue from the faces of travellers Gorée, island of serenity, awaits us. And yet Gorée holds memories of the infamous trade that once condemned thousands of the sons and daughters of Africa if not to death, then to an exile from which none returned. The rays of the morning sun turn the facades to bronze. Each has its story to tell, confusing all sense of where we are ; in a single narrow street we pass a building, a courtyard, a stairway, a door or a set of architectural features that remind us of Amsterdam, Oporto, Seville, Saint Tropez, New Orleans, Nantes, Brooklyn and perhaps even Damascus. But if Gorée were merely a succession of architectural images, it would be but a stage set. -

Practical Information – Dakar

Practical information – Dakar Dakar Dakar, capital of Senegal and one of the chief seaports on the western African coast. It is located midway between the mouths of the Gambia and Sénégal rivers on the south-eastern side of the Cape Verde Peninsula, close to Africa’s most westerly point. Dakar’s harbour is one of the best in Western Africa, being protected by the limestone cliffs of the cape and by a system of breakwaters. The city’s name comes from dakhar, a Wolof name for the tamarind tree, as well as the name of a coastal Lebu village that was located south of what is now the first pier. King Fahd Conference Centre The meetings will be held at the King Fahd Conference Centre which also houses the King Fahd Hotel. Those of you staying at the King Fahd Hotel can move from the lobby to the Conference Centre without leaving the building. The Yaas Hotel is the closest recommended hotel to the venue and is only 5 minutes away. Attached is a map of the King Fahd Conference Centre for reference. The Airport The main airport in Dakar is the Blaise Diagne International (DSS). Blaise Diagne International Airport is located on the east of the downtown of Dakar near the town of Diass. It is linked to the city via taxis, busses and shuttles. Travel to and from the Airport The Government of Senegal has kindly offered shuttle busses between the airport and the hotels recommended to the Secretariat. Please send Leah Krogsund ([email protected]) your arrival and departure dates and times should you require the use of these services. -

Ideologies of Honorific Language

Pragmatics2:3.25 l -262 InternationalPrasmatics Association IDEOLOGIES OF HONORIFIC LANGUAGE Judith T. Irvine 1. Introductionr All sociolinguisticsystems, presumably, provide some meansof expressingrespect (or disrespect);but only some systems have grammaticalized honorifics. This paper comparesseveral languages - Javanese,Wolof, and Zulu, plus a glance at ChiBemba - with regard to honorific expressionsand the social and cultural frameworks relevant thereto.2The main questionto be exploredis whether one can identiff any special cultural concomitants of linguistic systems in which the expression of respect is grammaticalized. Javanese"language levels" are a classicand well-describedexample of a system for the expressionof respect. In the sensein which I shall define "grammaticalized honorifics,"Javanese provides an apt illustration.Wolof, on the other hand, does not. Of course,Javanese is only one of several Asian languageswell known for honorific constructions,while Wolof, spokenin Senegal,comes from another part of the globe. But the presence or absence of honorifics is not an area characteristic of Asian languagesas opposed to African languages.As we shall see, Zulu has a system of lexicalalternates bearing a certain typological resemblanceto the Javanesesystem. Moreover,many other Bantu languages(such as ChiBemba) also have grammaticalized honorifics,but in the morphology rather than in the lexicon. Focusing on social structure instead of on geographical area, one might hypothesizethat grammaticalized honorifics occur where there are royal courts (Wenger1982) and in societieswhose traditions emphasize social rank and precedence. Honorificswould be a linguisticmeans of expressingconventionalized differences of rank.The languagesI shall comparewill make it evident,however, that a hypothesis causallylinking honorifics with court life or with entrenchedclass differences cannot be 1 An earlierversion of this paperwas presentedat a sessionon "Languageldeology" at the 1991annual meeting of the AmericanAnthropological Association. -

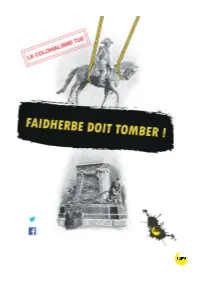

Statue Faidherbe

Une campagne à l’initiative de l’association Survie Nord à l’occasion du bicentenaire de la naissance de Louis Faidherbe le 3 juin 2018. En partenariat avec le Collectif Afrique, l’Atelier d’Histoire Critique, le Front uni des immigrations et des quartiers populaires (FUIQP), le Collectif sénégalais contre la célébration de Faidherbe . Consultez le site : faidherbedoittomber.org @ Abasfaidherbe Faidherbe doit tomber Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “père de l’impérialisme français” ? p. 4 Questions - réponses (à ceux qui veulent garder Faidherbe) p. 6 Qui était Louis Faidherbe ? p. 9 Un jeune Lillois sans éclat Un petit soldat de la conquête de l’Algérie Le factotum des affairistes Le « pacificateur » du Sénégal Un technicien du colonialisme Un idéologue raciste Une icône de la République coloniale Faidherbe vu du Sénégal p. 22 Aux origines lointaines de la Françafrique p. 29 Bibliographie p. 34 Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “ père de l’impérialisme français ” ? Depuis la fin du XIX e siècle, Lille et le nord de la France célèbrent perpétuellement la mémoire du gén éral Louis Faidherbe. Des rues et des lycées portent son nom. Des statues triomphales se dressent en son hommage au cœur de nos villes. Il y a là, pourtant, un scandale insup portable. Car Faidherbe était un colonialiste forcené. Il a massacré des milliers d’Africains au XIX e siècle. Il fut l’acteur clé de la conquête du Sénégal. Il défendit toute sa vie les théories racistes les plus abjectes. Si l’on considère que la colonisa tion est un crime contre l’humanité , il faut alors se rendre à l’évidence : celui que nos villes honorent quotidiennement est un criminel de haut rang. -

Multilingual Texting in Senegal

Names U ma puce: multilingual texting in Senegal Kristin Vold Lexander, University of Oslo [email protected] Working paper presented to the Media Anthropology Network e-seminar European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) 17-31 May 2011 http://www.media-anthropology.net/ Abstract Multilingualism is an important aspect of African urban life, also of the lives of students in Dakar. While the students usually write monolingual texts, mainly in French, their text messages involve the use of African languages too, in particular of the majority language Wolof, as well as Arabic and English, often mixed in one and the same message. With the rapid rise in the use of mobile phones, texting is becoming increasingly central as a means of communication for the students, and the social network with whom they text is growing. This working paper investigates texting as literacy practices (cf. Barton & Hamilton 1998), putting the accent on language choices: what role do they play in constructing these new practices? What are the motivations and the functions of the students’ languages choices? The analysis is based on six months of fieldwork in Dakar, during which I collected 496 SMS and interviewed and observed the 15 students who had sent and received the messages. I will focus on the practices of three of the students: Baba Yaro, a Fula-speaker born outside Dakar who has come to the Senegalese capital to undertake his studies, Christine, a Joola-speaker born in Dakar, and the Wolof-speaker Ousmane, from the suburb. I argue that in order to manage relationships and express different aspects of their identity, the students both exploit and challenge dominant language attitudes in their texting. -

Wolof Informational Report

Rhode Island College M.Ed. In TESL Program Language Group Specific Informational Reports Produced by Graduate Students in the M.Ed. In TESL Program In the Feinstein School of Education and Human Development Language Group: Wolof Author: Amanda Roy Program Contact Person: Nancy Cloud ([email protected]) Wolof Informational Report By: Amanda Roy TESL 539 Fall 2011 Where is Wolof Spoken? The language of Wolof belongs to the Atlantic branch of the Niger-Congo language family. It totals approximately 7 million speakers within the following countries. Senegal Gambia Mauritania France Guinea Guinea-Bissau Mali www.everyculture.com/Sa-Th/Senegal.html Writing System Wolof was first written in Wolofal which is a version of Arabic script. This is still used by some of the older male population in Senegal. http://www.omniglot.com/writing/wolof.htm Writing System Continued In 1974, the Wolof orthography using the Latin alphabet was standardized and became the official script in Senegal for Wolof. A a B b C c D d E e Ë ë F f G g I I J j K k L l M m N n Ñ ñŊŋ O o Pp Q q R r S s T t U u W w X x Y y Assane Faye, a Senegalese artist, also created an alphabet for Wolof in 1961. It goes from right to left and has some similarities to the Arabic script. Sometimes Wolof is written with this alphabet. http://www.omniglot.com/writing/wolof.htm What does Wolof sound like? Doomiaadamayéppdanuyjuddu, yam citawfeexci sag aksañ-sañ. -

Deepening Democracy and Cultural Context in the Republic of Mali, 1992-2002

DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND CULTURAL CONTEXT IN THE REPUBLIC OF MALI, 1992-2002 by JONATHAN MICHAEL SEARS A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Studies in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September 2007 Copyright © Jonathan Michael Sears, 2007 Abstract This thesis challenges the view that the Republic of Mali is a model of democratization in Africa with the aim of opening the conceptual framework of democratic citizenship inherent in the democratization discourse to greater critical scrutiny. The ‘enthusiastic’ view is held and set forth by various segments of the unity-seeking ruling class (local and foreign, State and NGO) of bringing to Mali a Western-oriented, procedurally minimal democracy, and citizen identity commensurate with international financial institutions’ and donor countries’ vision of democratization as political and economic liberalization. Consequently, this hegemonic project co-opts selected indigenous and Islamic idioms of political and social identity, to reinvent democratization as ‘moral governance.’ Cosmopolitan upper and upper-middle class actors thus apologize for highly personalized politics at the national and local levels, and articulate these more broadly with idioms of recovering rectitude and social cohesion that preserve and reproduce hierarchical social norms. In Malian political culture and in the scholarship of Malian political change, the hegemonic project of citizen identity formation becomes more evident as a construction, as discourses, norms, and practices produced and reproduced by privileged actors. Moreover, the contested character of these constructions becomes evident only as we address the development and deployment of selectively synthesized indigenous, Islamic, and Western-democratic norms, practices, and institutions of citizenship in contemporary Mali. -

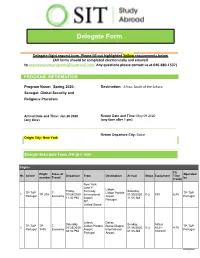

Delegate Form

Delegate Form Delegate flight request form. Please fill out highlighted Yellow requirements below (All forms should be completed electronically and emailed to [email protected]. Any questions please contact us at 646-880-1537) PROGRAM INFORMATION Program Name: Spring 2020: Destination: Africa, South of the Sahara Senegal: Global Security and Religious Pluralism Arrival Date and Time: Jan 26 2020 Return Date and Time: May 09 2020 (any time) (any time after 1 pm) Return Departure City: Dakar Origin City: New York Sample Schedule From JFK @ $ 1800 Flights Flt Flight Class of Operated Nr. Airline Departure From Destination Arrival Stops Equipment Time number Travel by (Total) New York, John F. Lisbon, Friday, Kennedy Saturday, TP-TAP T- Lisbon Portela TP-TAP 1 TP 208 01/24/2020 International 01/25/2020 0 () 339 6:35 Portugal Economy Airport, Portugal 11:30 PM Airport, 11:05 AM Portugal NY, United States Lisbon, Dakar, Saturday, Sunday, Airbus TP-TAP TP T- Lisbon Portela Blaise Diagne TP-TAP 2 01/25/2020 01/26/2020 0 () A321- 4:15 Portugal 1485 Economy Airport, International Portugal 08:50 PM 01:05 AM 100/200 Portugal Airport, 1 Delegate Form Dakar, Paris, Saturday, Sunday, AF-Air Q- Blaise Diagne Charles De Boeing 777- AF-Air 3 AF 719 05/09/2020 05/10/2020 0 () 5:30 France Economy International Gaulle Airport, 300 France 11:05 PM 06:35 AM Airport, France New York, John F. Paris, Sunday, Kennedy Sunday, AF-Air Q- Paris Orly Boeing 777- AF-Air 4 AF 032 05/10/2020 International 05/10/2020 0 () 8:25 France Economy Airport, 200 France 02:15 PM Airport, 04:40 PM France NY, United States Nonrefundable Changeable for a fee 2 bags permitted with AF, Zero bag with TP Please see below for Personal Details. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

February 2011

The Journal of Indian Education is a quarterly periodical published every year in May, August, November and February by the National Council of Educational Research and Training, New Delhi. The purpose is to provide a forum for teachers, teacher-educators, educational administrators and research workers; to encourage original and critical thinking in education through presentation of novel ideas, critical appraisals of contemporary educational problems and views and experiences on improved educational practices. The contents include thought-provoking articles by distinguished educationists, challenging discussions, analysis of educational issues and problems, book reviews and other features. Manuscripts along with computer soft copy, if any, sent in for publication should be exclusive to the Journal of Indian Education. These, along with the abstracts, should be in duplicate, typed double-spaced and on one side of the sheet only, addressed to the Academic Editor, Journal of Indian Education, Department of Teacher Education, NCERT, Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi 110 016. The Journal reviews educational publications other than textbooks. Publishers are invited to send two copies of their latest publications for review. Copyright of the articles published in the Journal will vest with the NCERT and no matter may be reproduced in any form without the prior permission of the NCERT. Academic Editor Raj Rani Editorial Committee Ranjana Arora Kiran Walia Yogesh Kumar Anupam Ahuja M.V. Srinivasan Lungthuiyang Riamei (JPF) Publication Team Head, Publication Division : Ashok Srivastava Chief Production Officer : Shiv Kumar Chief Editor (Incharge) : Naresh Yadav Chief Business Manager : Gautam Ganguly Assistant Editor : Hemant Kumar Assistant Production Officer : Abdul Naim Cover Amit Kumar Srivastava Single Copy : Rs.