Ideologies of Honorific Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2012 The nbU ought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N. Boggs Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boggs, Richard N., "The nbouU ght Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature" (2012). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 21. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/21 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Mentor: Dr. Thomas Cook Reader: Dr. Gail Sinclair Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature By Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Project Approved: ________________________________________ Mentor ________________________________________ Reader ________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Dedicated to my wife Elizabeth for her love, her patience and her unceasing support. CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Greek Pre-Chivalry 5 III. Roman Pre-Chivalry 11 IV. The Rise of Christian Chivalry 18 V. The Age of Chivalry 26 VI. -

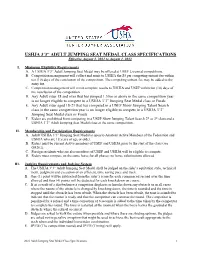

Ushja 3'3” Jumping Seat Medal Class Specifications

USHJA 3’3” ADULT JUMPING SEAT MEDAL CLASS SPECIFICATIONS Effective August 2, 2021 to August 1, 2022. I. Minimum Eligibility Requirements A. A USHJA 3’3” Adult Jumping Seat Medal may be offered at USEF Licensed competitions. B. Competition management will collect and remit to USHJA the $5 per competing entrant fee within ten (10) days of the conclusion of the competition. The competing entrant fee may be added to the entry fee. C. Competition management will remit complete results to USHJA and USEF within ten (10) days of the conclusion of the competition. D. Any Adult rider 18 and over that has jumped 1.30m or above in the same competition year is no longer eligible to compete in a USHJA 3’3” Jumping Seat Medal class or Finals E. Any Adult rider aged 18-21 that has competed in a USEF Show Jumping Talent Search class in the same competition year is no longer eligible to compete in a USHJA 3’3” Jumping Seat Medal class or Finals F. Riders are prohibited from competing in a USEF Show Jumping Talent Search 2* or 3* class and a USHJA 3’3” Adult Jumping Seat Medal class at the same competition. II. Membership and Participation Requirements A. Adult USHJA 3’3” Jumping Seat Medal is open to Amateur Active Members of the Federation and USHJA who are 18 years of age or older. B. Riders must be current Active members of USEF and USHJA prior to the start of the class (see GR202). C. Foreign residents who are also members of USEF and USHJA will be eligible to compete. -

Nursing Leadership Fellowship

C HILDREN’ S H OSPITAL OF P ITTSBURGH OF UPMC Nursing Leadership Fellowship Fellow Workbook FY2016 Nursing Leadership Fellowship Fellow Workbook FY2016 2 C HILDREN’ S H OSPITAL OF P ITTSBURGH OF UPMC Nursing Leadership Fellowship Fellow Workbook Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction to the Nursing Leadership Fellowship Program Overview Fellow Workbook Utilization Section 2: Fellowship Planning and Orientation Pre-fellowship Course Work Program Expectations Timeline and Calendars Enrichment Experiences Role of the Advisor Section 3: First Quarter Curriculum Communication and Relationship-Building Knowledge of the Health Care Environment Leadership Skills Professionalism Business Skills, Financials, and Human Resources Management Section 4: Second Quarter Curriculum Communication and Relationship-Building Knowledge of the Health Care Environment Leadership Skills Professionalism Business Skills, Financials, and Human Resources Management Section 5: Third Quarter Curriculum Communication and Relationship-Building Knowledge of the Health Care Environment Leadership Skills Professionalism Business Skills, Financials, and Human Resources Management Section 6: Fourth Quarter Curriculum Communication and Relationship-Building Knowledge of the Health Care Environment Leadership Skills Professionalism Business Skills, Financials, and Human Resources Management 3 C HILDREN’ S H OSPITAL OF P ITTSBURGH OF UPMC Nursing Leadership Fellowship Fellow Workbook Table of Contents Bibliography Didactic Classroom Schedules Appendices: Forms Goal Setting -

Student Title Page Guide

7th Edition Student Title Page Guide NOTE: These guidelines should be used to create title pages for student papers. However, if instructors or institutions provide different guidance, students should abide by those directions. TITLE PAGE: The title page needs to provide information about the paper’s topic and authors and the course to which it is being submitted. Title Page Content • affiliation is usually the university the author(s) attended A student title page includes the following elements: ° ° include the name of the department or • title of the paper division, followed by the name of the university, • author(s) separated by a comma (e.g., Department of ° include the full names of all authors of the Psychology, University of Nebraska) paper; use the form first name, middle initial, • course name and number last name (e.g., Betsy R. Klein) ° use the format shown on institutional materials ° if two authors, separate with the word “and” for the course to which the paper is being (e.g., Ainsley E. Baum and Lucy K. Reid) submitted (e.g., PSY 202, NURS101) if three or more authors, separate each name ° • instructor name with a comma and write the word “and” before the last author (e.g., Riley S. Rodrigo, Dev M. ° use the instructor’s preferred designation Kumar, and Aidan T. Zhang) (e.g., Dr., Professor) and spelling • assignment due date ° for names with suffixes, separate the suffix from the rest of the name with a space, not a ° use the month, date, and year format used in comma (e.g., Felicien L. Cooke Jr.) your country ° spell out the month (e.g., March 6, 2020) • header with the page number Title Page Format Special Considerations • recommended fonts: 11-point Calibri, 11-point for the Paper Title Arial, 10-point Lucida Sans Unicode, 12-point • written in title case Times New Roman, 11-point Georgia, or 10-point Computer Modern1 ° capitalize the first word of the title and the first word of any subtitle (after a colon, dash, etc.) • 1-in. -

Multilingual Texting in Senegal

Names U ma puce: multilingual texting in Senegal Kristin Vold Lexander, University of Oslo [email protected] Working paper presented to the Media Anthropology Network e-seminar European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) 17-31 May 2011 http://www.media-anthropology.net/ Abstract Multilingualism is an important aspect of African urban life, also of the lives of students in Dakar. While the students usually write monolingual texts, mainly in French, their text messages involve the use of African languages too, in particular of the majority language Wolof, as well as Arabic and English, often mixed in one and the same message. With the rapid rise in the use of mobile phones, texting is becoming increasingly central as a means of communication for the students, and the social network with whom they text is growing. This working paper investigates texting as literacy practices (cf. Barton & Hamilton 1998), putting the accent on language choices: what role do they play in constructing these new practices? What are the motivations and the functions of the students’ languages choices? The analysis is based on six months of fieldwork in Dakar, during which I collected 496 SMS and interviewed and observed the 15 students who had sent and received the messages. I will focus on the practices of three of the students: Baba Yaro, a Fula-speaker born outside Dakar who has come to the Senegalese capital to undertake his studies, Christine, a Joola-speaker born in Dakar, and the Wolof-speaker Ousmane, from the suburb. I argue that in order to manage relationships and express different aspects of their identity, the students both exploit and challenge dominant language attitudes in their texting. -

Wolof Informational Report

Rhode Island College M.Ed. In TESL Program Language Group Specific Informational Reports Produced by Graduate Students in the M.Ed. In TESL Program In the Feinstein School of Education and Human Development Language Group: Wolof Author: Amanda Roy Program Contact Person: Nancy Cloud ([email protected]) Wolof Informational Report By: Amanda Roy TESL 539 Fall 2011 Where is Wolof Spoken? The language of Wolof belongs to the Atlantic branch of the Niger-Congo language family. It totals approximately 7 million speakers within the following countries. Senegal Gambia Mauritania France Guinea Guinea-Bissau Mali www.everyculture.com/Sa-Th/Senegal.html Writing System Wolof was first written in Wolofal which is a version of Arabic script. This is still used by some of the older male population in Senegal. http://www.omniglot.com/writing/wolof.htm Writing System Continued In 1974, the Wolof orthography using the Latin alphabet was standardized and became the official script in Senegal for Wolof. A a B b C c D d E e Ë ë F f G g I I J j K k L l M m N n Ñ ñŊŋ O o Pp Q q R r S s T t U u W w X x Y y Assane Faye, a Senegalese artist, also created an alphabet for Wolof in 1961. It goes from right to left and has some similarities to the Arabic script. Sometimes Wolof is written with this alphabet. http://www.omniglot.com/writing/wolof.htm What does Wolof sound like? Doomiaadamayéppdanuyjuddu, yam citawfeexci sag aksañ-sañ. -

Awards for Every Ocassion

awards for every ocassion stock rosettes stock ribbons roll ribbons banners & pennants custom rosettes custom certificates beauty sashes awareness ribbons Table of Contents Custom Rosettes .......................................................... 3-13 Awards & Ribbons Catalog Custom Printed Ribbons..................................................14 When you’re looking for quality award and ribbon items, look Stock Ribbons & Rosettes ..............................................15 no further. We have taken the time and have the expertise to carefully handcraft our satin ribbons and rosettes for your Neck Ribbons & Beauty Sashes ...................................16 business! Choose from dozens of styles, sizes, colors and Tiaras & Scepters ............................................................17 award ribbon items to suit your many needs. Stock & Custom Certificates ..........................................18 • Various Rosette Designs • Custom Options Specialty Ribbons ............................................................19 • Numerous Imprint Color Choices Celluloid Buttons ..............................................................20 • Buttons, Certificates & More Color Chart ........................................................................21 Stock Logos................................................................. 22-23 Telephone Orders We want to produce your job right the first time, so we ask that large orders or orders requiring changes are in writing to reduce the possibility of errors. Quotes given -

English Style Guide: a Handbook for Translators, Revisers and Authors of Government Texts

clear writing #SOCIAL MEDIA ‘Punctuation!’ TRANSLATING Useful links English Style Guide A Handbook for Translators, Revisers and Authors of Government Texts Second edition ABBREVIATIONSediting June 2019 Publications of the Prime Minister’s Oce 2019 :14, Finland The most valuable of all talents is that Let’s eat, Dad! of never using two words when one will do. Let’s eat Dad! Thomas Jefferson Translation is not a matter of words only: it is A translation that is clumsy or a matter of making intelligible a whole culture. stilted will scream its presence. Anthony Burgess Anonymous One should aim not at being possible to understand, Without translation I would be limited but at being impossible to misunderstand. to the borders of my own country. Quintilian Italo Calvino The letter [text] I have written today is longer than Writing is thinking. To write well is usual because I lacked the time to make it shorter. to think clearly. That's why it's so hard. Blaise Pascal David McCullough 2 Publications of the Prime Minister’s Office 2019:14 English Style Guide A Handbook for Translators, Revisers and Authors of Government Texts Second edition June 2019 Prime Minister’s Office, Helsinki, Finland 2019 2 Prime Minister’s Office ISBN: 978-952-287-671-3 Layout: Prime Minister’s Office, Government Administration Department, Publications Helsinki 2019 ISTÖM ÄR ER P K M K Y I M I KT LJÖMÄR Painotuotteet Painotuotteet1234 5678 4041-0619 4 Description sheet Published by Prime Minister’s Office, Finland 28 June 2019 Authors Foreign Languages Unit, Translation -

Annex H. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Senegal

Annex H. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Senegal Geography and Demographics 196,722 square Size: kilometers (km2) Population: 14 million (2015) Capital: Dakar Urban: 44% (2015) Administrative 14 regions Divisions: Religion: 95% Muslim 4% Christian 1% Traditional Source: Central Intelligence Agency (2015). Note: Population and percentages are rounded. Literacy Projected 2013 Primary School 2015 Age Population (aged 2.2 million Literacy a a 7–12 years): Rates: Overall Male Female Adult (aged 2013 Primary School 56% 68% 44% 84%, up from 65% in 1999 >15 years) GER:a Youth (aged 2013 Pre-primary School 70% 76% 64% 15%,up from 3% in 1999 15–24 years) GER:a Language: French Mean: 18.4 correct words per minute When: 2009 Oral Reading Fluency: Standard deviation: 20.6 Sample EGRA Where: 11 regions 18% zero scores Resultsb 11% reading with ≥60% Reading comprehension Who: 687 P3 students Comprehension: 52% zero scores Note: EGRA = Early Grade Reading Assessment; GER = Gross Enrollment Rate; P3 = Primary Grade 3. Percentages are rounded. a Source: UNESCO (2015). b Source: Pouezevara et al. (2010). Language Number of Living Languages:a 210 Major Languagesb Estimated Populationc Government Recognized Statusd 202 DERP in Africa—Reading Materials Survey Final Report 47,000 (L1) (2015) French “Official” language 3.9 million (L2) (2013) “National” language Wolof 5.2 million (L1) (2015) de facto largest LWC Pulaar 3.5 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Serer-Sine 1.4 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Maninkakan (i.e., Malinké) 1.3 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Soninke 281,000 (L1) (2015) “National” language Jola-Fonyi (i.e., Diola) 340,000 (L1) “National” language Balant, Bayot, Guñuun, Hassanya, Jalunga, Kanjaad, Laalaa, Mandinka, Manjaaku, “National” languages Mankaañ, Mënik, Ndut, Noon, __ Oniyan, Paloor, and Saafi- Saafi Note: L1 = first language; L2 = second language; LWC = language of wider communication. -

Pronominal Reference in Thai, Burmese, and Vietnamese

Pronominal Reference in Thai, Burmese, and Vietnamese By Joseph Robinson Cooke B.Th. (Biola College, Los Angeles) 19^9 A.B. (Biola College, Los Angeles) 1952 A.B. (University of California) 1961 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Approved: "> Committee in Charge Degree conferred Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study has been prepared as a doctoral dissertation in Linguistics, for presentation to the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley, in 1965* Ik is the result of some eighteen months of research undertaken between November, 1963 and May, 1965i and it has been made possible largely by the financial aid of the American Council of Learned Societies. This aid has enabled me to devote full time to my studies and to complete the task more quickly and easily than would otherwise have been possible. I cannot sufficiently express my appreciation for the help and advice of those who have directed my research. Foremost among these is Professor Mary R. Haas, whose constant interest, encouragement, suggestions, and careful attention to detail have contributed immeasurably to any merits that the present study may possess. I have also profited materially from the help and encouragement of Professors Murray B. Emeneau and Kun Chang, who have shared responsibility for directing my work. I am in debt, too, to a rather large number of Thai, Burmese and Vietnamese informants. These have given in valuable assistance in my work,with their helpfulness, con sideration, interest, and cooperation.