Gorée: Island of Memories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

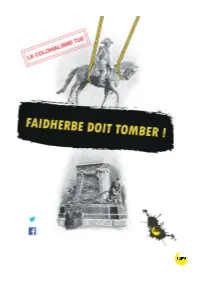

Statue Faidherbe

Une campagne à l’initiative de l’association Survie Nord à l’occasion du bicentenaire de la naissance de Louis Faidherbe le 3 juin 2018. En partenariat avec le Collectif Afrique, l’Atelier d’Histoire Critique, le Front uni des immigrations et des quartiers populaires (FUIQP), le Collectif sénégalais contre la célébration de Faidherbe . Consultez le site : faidherbedoittomber.org @ Abasfaidherbe Faidherbe doit tomber Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “père de l’impérialisme français” ? p. 4 Questions - réponses (à ceux qui veulent garder Faidherbe) p. 6 Qui était Louis Faidherbe ? p. 9 Un jeune Lillois sans éclat Un petit soldat de la conquête de l’Algérie Le factotum des affairistes Le « pacificateur » du Sénégal Un technicien du colonialisme Un idéologue raciste Une icône de la République coloniale Faidherbe vu du Sénégal p. 22 Aux origines lointaines de la Françafrique p. 29 Bibliographie p. 34 Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “ père de l’impérialisme français ” ? Depuis la fin du XIX e siècle, Lille et le nord de la France célèbrent perpétuellement la mémoire du gén éral Louis Faidherbe. Des rues et des lycées portent son nom. Des statues triomphales se dressent en son hommage au cœur de nos villes. Il y a là, pourtant, un scandale insup portable. Car Faidherbe était un colonialiste forcené. Il a massacré des milliers d’Africains au XIX e siècle. Il fut l’acteur clé de la conquête du Sénégal. Il défendit toute sa vie les théories racistes les plus abjectes. Si l’on considère que la colonisa tion est un crime contre l’humanité , il faut alors se rendre à l’évidence : celui que nos villes honorent quotidiennement est un criminel de haut rang. -

Cultural Representations of Massacre Reinterpretations of the Mutiny of Senegal

Copyrighted Material - 9781137274960 Cultural Representations of Massacre Reinterpretations of the Mutiny of Senegal Sabrina Parent Copyrighted Material - 9781137274960 Copyrighted Material - 9781137274960 CULTURAL REPRESENTATIONS OF MASSACRE Copyright © Sabrina Parent, 2014. All rights reserved. First published in 2014 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States— a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN: 978- 1- 137- 27496- 0 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Parent, Sabrina, author. Cultural representations of massacre : reinterpretations of the mutiny of Senegal / by Sabrina Parent. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 1- 137- 27496- 0 (alk. paper) 1. African literature (French)—20th century— History and criticism. 2. France. Armée. Tirailleurs sénégalais—In literature. 3. France. Armée. Tirailleurs sénégalais—In motion pictures. 4. Massacres in literature. 5. Massacres—Senegal— Thiaroye- sur- Mer— In motion pictures. 6. Thiaroye- sur- Mer (Senegal)— In literature. 7. Thiaroye- sur- Mer (Senegal)— In motion pictures. 8. Senegal— Colonization— In literature. 9. Senegal— Colonization— In motion pictures. 10. France— Colonies— Africa— Administration. I. Title. PQ3980.5.P37 2014 840.9’35866303— dc23 2014000297 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. -

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal –

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal – Key terms: Assimilation Association Direct rule Mission Dakar–Djibouti Direct Rule Direct rule is a system whereby the colonies were governed by European officials at the top position, then Natives were at the bottom. The Germans and French preferred this system of administration in their colonies. Reasons: This system enabled them to be harsh and use force to the African without any compromise, they used the direct rule in order to force African to produce raw materials and provide cheap labor The colonial powers did not like the use of chiefs because they saw them as backward and African people could not even know how to lead themselves in order to meet the colonial interests It was used to provide employment to the French and Germans, hence lowering unemployment rates in the home country Impacts of direct rule It undermined pre-existing African traditional rulers replacing them with others It managed to suppress African resistances since these colonies had enough white military forces to safeguard their interests This was done through the use of harsh and brutal means to make Africans meet the colonial demands. Assimilation (one ideological basis of French colonial policy in the 19th and 20th centuries) In contrast with British imperial policy, the French taught their subjects that, by adopting French language and culture, they could eventually become French and eventually turned them into black Frenchmen. The famous 'Four Communes' in Senegal were seen as proof of this. Here Africans were granted all the rights of French citizens. -

Final Report

P a g e | 1 Final Report Senegal: Floods in Dakar and Thiès DREF operation Operation n° MDRSN017 Date of Issue: 27 August 2021 Glide number: FL-2020-000198-SEN Operation start date: 12 September 2020 Operation end date: 31 March 2021 Host National Society: Operation budget: CHF 331,410 Number of people affected: 16,798 affected people Number of people assisted: 900 households (8,100 (5,879 men and 10,919 women) people) directly reached. Overall, 60,720 people (10,120) reached through awareness visits Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: IFRC, ICRC, Belgian and Spanish Red Cross Societies and the Turkish Red Crescent. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Civil Protection, Sanitation Directorate, and Territorial and Municipal Authorities The major donors and partners of the Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) include the Red Cross Societies and governments of Belgium, Britain, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, Republic of Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland, as well as DG ECHO and Blizzard Entertainment, Mondelez International Foundation, and Fortive Corporation and other corporate and private donors. DG ECHO and the Canadian Government contributed to replenishing the DREF for this operation. On behalf of the Senegalese Red Cross Society (SRCS), the IFRC would like to extend gratitude to all for their generous contributions. <click here for the final financial report and here for contacts> A. SITUATION ANALYSIS Description of the disaster Senegal experienced heavy rainfall during the rainy season of 2020, exceeding the average amounts usually experienced during that period. -

Chapter 3: Dakar

DAKAR Capital cities 1.indd 31 9/22/11 4:20 PM DAKAR 3 Amadou Diop During the 20th century, the city of Dakar figured as the capital city of several territories, including countries such as Mali and Gambia. This attests to the central role it has played, and continues to play, in West Africa. Today, Dakar is firmly established as the capital of Senegal. A port city with a population of over 2.5 million and a location on a peninsula which continues to attract people from the country’s hinterland, Dakar has grown rapidly. It is administratively known as the Dakar Region, and comprises four départements (administrative districts) (see Figure 3.1) – Dakar, the original old city with a population of 1 million; Pikine, a large, sprawling department with a population of some 850 000; and Guédiawaye and Rufisque, two smaller departments of some 300 000 residents each (Diop 2008). The latter two represent the most recent peri-urban incorporation of settlements in the Dakar Region. Each of the four departments, in turn, comprise a number of communes, or smaller administrative units. This chapter is divided into two main parts. The first, ‘The urban geology of Dakar’, commences with a short history of the establishment and growth of the city, its economy and population. Subsequent sections discuss urban-planning activities before and after independence, government attempts through policy and practice to address the urban housing and urban transport challenges, and attempts to plan secondary commercial centres in the Dakar Region as more and more urban settlements are developed at some distance from the city centre of Dakar. -

A Historical Analysis of French and Senegal Cultural Relationship

FROM IMPERIALISM TO DIPLOMACY: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF FRENCH AND SENEGAL CULTURAL RELATIONSHIP BY AISHA BALARABE BAWA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY USMANU DANFODIYO UNIVERSITY, SOKOTO EMAIL:[email protected] Being a paper presented at the London Art as Cultural Diplomacy Conference 2013 on the theme: “Contemporary International Dialogue: Art-Based Developments and Culture shared between nations” Held at The Portcullis House, British Parliament from 21st to 24th August 2013. 1 Introduction France and Senegal shared a special relationship for over 300 years that date back to the 17th century. Saint- Louis was the first permanent French settlement in Senegal. Its geographical position meant that it commanded trade along the Senegal River. The four communes of Senegal (Goree, Dakar, Rufisque, and Saint- Louis) were the only place during the African colonial period, where African inhabitants were granted the same right as French. As the capital of French West Africa during the colonial period, Senegal was France‟s most important African territory. The French had a more concentrated and central presence there than in other colonies, so its culture became particularly ingrained into Senegalese life. The two countries have maintained the close ties since political independence. In spite Senegal obtaining it independence in 1960, it has maintained a positive relationship with France, and many elements of French culture introduced during the colonial period remain an important part of Senegalese identity. This paper examines the colonial language policy of French in Senegal as a form of cultural relationship between two nations. Overview of Literature Since the beginning of the 1960s, there have been a number of studies devoted in part or entirely to French colonial language policy in Africa. -

Dakar Regional Express Train (Ter)

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : DAKAR REGIONAL EXPRESS TRAIN (TER) COUNTRY : SENEGAL SUMMARY OF THE STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SESA) Project Team: A. I. MOHAMED, Principal Transport Economist, OITC1/SNFO M. A. WADE, Infrastructure Specialist, SNFO/OITC1 M. MBODJ, Consulting Economist, OITC 2 M. L. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist, ONEC.3 S. BAIOD, Consultant Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Project Team Sector Director: A. OUMAROU Regional Director: A. BERNOUSSI Acting Resident Representative: A. NSIHIMYUMUREMYI Division Manager: J. K. KABANGUKA 1 Dakar Regional Express Train (TER) Summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment Project name : DAKAR REGIONAL EXPRESS TRAIN (TER) Country : SENEGAL Project code : P-SN-DC0-003 Department : OITC Division : OITC.1 1 Introduction This report is the summary of the Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) of the Dakar Regional Express Train Project. It is prepared in accordance with African Development Bank (AfDB) procedures and operational policies, through its Integrated Safeguards System (ISS) for Category 1 projects. The project description and rationale are first presented, followed by the legal and institutional framework in Senegal. A brief description of the main environmental conditions is presented and the railway project’s components are presented according to typology. This project summary, in its Phase 1, identifies the key issues relating to major impacts and the types of measures to mitigate them. It encompasses the Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) developed for this purpose. It defines the environmental assessment procedures to be followed by key project actors and partners in the various stages with regard to the Design/Implementation approach. The regulatory and organizational mitigation measures and actions to check, minimize, mitigate or offset the negative impacts are presented in the report. -

Study of the Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change of Coastal Areas in Public Disclosure Authorized Senegal

REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL GOVERNMENT OF SENEGAL ONE PEOPLE – ONE GOAL – ONE FAITH - DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CLASSIFIED ESTABLISHMENTS Public Disclosure Authorized WORLD BANK Economic and Spatial Study of the Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change of Coastal Areas in Public Disclosure Authorized Senegal Synthesis Report Final Version Public Disclosure Authorized August 2013 Public Disclosure Authorized World Bank Economic and Spatial Study of the Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change of Coastal Areas in Senegal TABLE OF CONTENTS ________ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 RESUME EXECUTIF 11 1. INTRODUCTION 21 1.1. CONTEXT OF THE STUDY 21 1.2. STUDY OBJECTIVES AND APPROACH 22 1.3. CONTENT OF THIS REPORT 23 2. NATURAL RISKS AND CLIMATE CHANGE ON THE SENEGALESE COASTLINE 24 2.1. A COASTLINE SEGMENTATION BASED ON LAND OCCUPATION 24 2.2. A COASTLINE CHARACERIZED BY A STRONG GROWTH OF URBAN VULNERABILITIES 26 2.3. A CLIMATE MARKED BY DROUGHT AND MAJOR UNCERTAINTIES FOR THE FUTURE 29 2.4. A COASTLINE SEVERELY THREATENED BY NATURAL AND CLIMATE-RELATED HAZARDS 32 2.5. AGGRAVATION OF RISKS DUE TO CLIMATE EVOLUTION 38 3. IN-DEPTH STUDY AT THREE PILOT SITES 43 3.1. SELECTION OF THE THREE PILOT SITES 44 3.2. SITES SHOWING HIGH VULNERABILITIES RELATED TO URBANIZATION, AND INCREASING OVER TIME 44 3.3. POPULATIONS THREATENED, ON VARIOUS ACCOUNTS, BY THE ENCROACHMENT OF THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT 48 3.4. CLIMATE FORECASTS SHOWING A NORTH-SOUTH GRADIENT, WITH POSSIBLE TREND REVERSALS 50 3.5. GROUNDWATER RESOURCES MAINLY THREATENED BY HUMAN ACTIVITIES, BUT A POTENTIAL IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE IN SALY 50 3.6. -

Saint-Louis (Senegal) No

Company, and the English occupied Saint-Louis on three Saint-Louis (Senegal) occasions, in 1693, in 1779, and from 1809 to 1817. Initially unhealthy and inhospitable, the island also lacked building materials, until it was discovered that the plentiful No 956 masses of oysters could serve for lime production and road construction. Gradually the settlement of Saint-Louis developed its commercial activities, trading rubber, leather, gold, ivory, and cereals as well as dealing in slaves. To these were added the need for education and building of schools. At the beginning of the 19th century the settlement had some Identification 8000 inhabitants. In 1828 an urban master plan established the street pattern and regulated the development of the town, Nomination Island of Saint-Louis (Ile de Saint- starting from the old fortification as the basic reference. The Louis) real development of the town, however, took place from 1854, when Louis Faidherbe was nominated governor. Thus Location Region of Saint-Louis from 1854 to 1865 Saint-Louis was urbanized. It was nominated the capital of Senegal in 1872 and reached its State Party Senegal apogee in 1895 when it was nominated the capital of West Africa. Date 17 September 1998 In this period Saint-Louis became the leading urban centre in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as the centre for the diffusion of cultural and artistic activities. The first museum of the industry, ethnography, and history of West Africa was opened in Saint-Louis on 15 March 1864. In this period the Justification by State Party schools and other public institutions and services, as well as the first Senegalese military battalion, and a Muslim court of The historic centre of Saint-Louis is a colonial town; it is justice, were established. -

Illicit Drug Trading in Dakar Dimensions and Intersections with Governance Boubacar Diarisso and Charles Goredema

ISS PAPER 260 | AUGUST 2014 Illicit drug trading in Dakar Dimensions and intersections with governance Boubacar Diarisso and Charles Goredema Summary The authors provide a thorough analysis of the situation with regard to illegal drugs in Senegal’s capital, Dakar. The paper focuses on cannabis, cocaine and heroine, as well as counterfeit pharmaceutical products. It discusses the extent of cultivation, patterns of consumption, international trafficking methods and routes, the role of women, police action and the impact of trafficking on governance. It is concluded that while there is no evidence that hard drugs are manufactured in Dakar and there are insufficient indicators for Dakar being a drug trafficking hub, it is evident that crime networks are interested in exploiting the city for the channelling of drugs to other parts of the world. ONCE THE CAPITAL OF French West During the 18th century Dakar was as a crucial link in international relations Africa during the colonial period from nothing more than a village. The name and affairs.5 1902 to 1958, and then of the short- reportedly featured on a map for the Dakar boasts a telecommunications and lived Mali Federation in 1959, the city of first time in 1750.3 The first buildings infrastructure network that makes the Dakar became the political and economic appeared in 1857 in the wake of the city a favourite destination for cultural, capital of the newly independent state construction of a French fort. This political and economic events of an of Senegal in 1960. As one of the was followed by the design of an initial international nature. -

Project for Urban Master Plan of Dakar and Neighboring Area for 2035 Final Report Volume. I

No. Ministry of Urban Renewal, Japan International Cooperation Housing and Living Environment Agency (JICA) Republic of Senegal Project for Urban Master Plan of Dakar and Neighboring Area for 2035 Final Report Volume. I January 2016 Implemented by: RECS International Inc. Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. PACET Corp. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Asia Air Survey Co., Ltd. EI JR 16-002 Ministry of Urban Renewal, Japan International Cooperation Housing and Living Environment Agency (JICA) Republic of Senegal Project for Urban Master Plan of Dakar and Neighboring Area for 2035 Final Report Volume. I January 2016 Implemented by: RECS International Inc. Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. PACET Corp. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Asia Air Survey Co., Ltd. Currency Equivalents (average Interbank rates between May and July, 2015) US$1.00= FCFA 594.04 €1.00= FCFA 659.95 Source: Banque Centrale des Etats de l'Afrique de l'Ouest (BCEAO) Rate Project for Urban Master Plan of Dakar and Neighboring Area for 2035 Final Report: Volume. I Table of Contents Volume. I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives ............................................................................................................................. 1-3 1.3 Study Area ............................................................................................................................