Chapter 3: Dakar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Road Travel Report: Senegal

ROAD TRAVEL REPORT: SENEGAL KNOW BEFORE YOU GO… Road crashes are the greatest danger to travelers in Dakar, especially at night. Traffic seems chaotic to many U.S. drivers, especially in Dakar. Driving defensively is strongly recommended. Be alert for cyclists, motorcyclists, pedestrians, livestock and animal-drawn carts in both urban and rural areas. The government is gradually upgrading existing roads and constructing new roads. Road crashes are one of the leading causes of injury and An average of 9,600 road crashes involving injury to death in Senegal. persons occur annually, almost half of which take place in urban areas. There are 42.7 fatalities per 10,000 vehicles in Senegal, compared to 1.9 in the United States and 1.4 in the United Kingdom. ROAD REALITIES DRIVER BEHAVIORS There are 15,000 km of roads in Senegal, of which 4, Drivers often drive aggressively, speed, tailgate, make 555 km are paved. About 28% of paved roads are in fair unexpected maneuvers, disregard road markings and to good condition. pass recklessly even in the face of oncoming traffic. Most roads are two-lane, narrow and lack shoulders. Many drivers do not obey road signs, traffic signals, or Paved roads linking major cities are generally in fair to other traffic rules. good condition for daytime travel. Night travel is risky Drivers commonly try to fit two or more lanes of traffic due to inadequate lighting, variable road conditions and into one lane. the many pedestrians and non-motorized vehicles sharing the roads. Drivers commonly drive on wider sidewalks. Be alert for motorcyclists and moped riders on narrow Secondary roads may be in poor condition, especially sidewalks. -

Gorée: Island of Memories

GOREE ISLAND OF MEMORIES GOREE ISLAND OF MEMORIES Unesco The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Unesco concerning the legal status of any country territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published in 1985 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7 place de Fontenoy, 75700 Paris Printed by L. Vanmelle, Ghent, Belgium ISBN 92-3-102348-9 French edition 92-3-202348-2 © Unesco 1985 Printed in Belgium PREFACE Scarely have the lights of Dakar dimmed on the horizon than the launch puts in at the little harbour of Gorée. Half an hour has passed, just long enough for the sea-breeze to smooth away, as if by magic, the lines of fatigue from the faces of travellers Gorée, island of serenity, awaits us. And yet Gorée holds memories of the infamous trade that once condemned thousands of the sons and daughters of Africa if not to death, then to an exile from which none returned. The rays of the morning sun turn the facades to bronze. Each has its story to tell, confusing all sense of where we are ; in a single narrow street we pass a building, a courtyard, a stairway, a door or a set of architectural features that remind us of Amsterdam, Oporto, Seville, Saint Tropez, New Orleans, Nantes, Brooklyn and perhaps even Damascus. But if Gorée were merely a succession of architectural images, it would be but a stage set. -

An Ambiguous Partnership: Great Britain and the Free French Navy, 1940-19421

An Ambiguous Partnership: Great Britain and the Free French Navy, 1940-19421 Hugues Canuel On se souvient aujourd’hui des forces de la France libre en raison de faits d’armes tels que leur courageuse résistance à Bir Hakeim en 1942 et la participation du général Leclerc à la libération de Paris en 1944. Par contre, la contribution antérieure de la marine de la France libre est moins bien connue : elle a donné à de Gaulle, dont l’espoir était alors bien mince, les moyens de mobiliser des appuis politiques au sein de l’empire colonial français et d’apporter une contribution militaire précoce à la cause des Alliés. Cette capacité s’est développée à la suite de l’appui modeste mais tout de même essentiel du Royaume-Uni, un allié qui se méfiait de fournir les ressources absolument nécessaires à une flotte qu’il ne contrôlait pas complètement mais dont les actions pourraient aider la Grande- Bretagne qui se trouvait alors presque seule contre les puissances de l’Axe. Friday 27 November 1942 marked the nadir of French sea power in the twentieth century. Forewarned that German troops arrayed around the Mediterranean base of Toulon were intent on seizing the fleet at dawn, Admiral Jean de Laborde – Commander of the Force de Haute Mer, the High Seas Force – and the local Maritime Prefect, Vice Admiral André Marquis, ordered the immediate scuttling of all ships and submarines at their berths. Some 248,800 tons of capital ships, escorts, auxiliaries and submarines was scuttled as the Wehrmacht closed in on the dockyard.2 The French “Vichy navy” virtually ceased to exist that day. -

BANK of AFRICA SENEGAL Prie Les Personnes Dont Les Noms Figurent

COMMUNIQUE COMPTES INACTIFS BANK OF AFRICA SENEGAL prie les personnes dont les noms figurent sur la liste ci- dessous de bien vouloir se présenter à son siège (sis aux Almadies, Immeuble Elan, Rte de Ngor) ou dans l’une de ses agences pour affaire les concernant AGENCE DE NOM NATIONALITE CLIENT DOMICILIATION KOUASSI KOUAME CELESTIN COTE D'IVOIRE ZI PARTICULIER 250383 MME SECK NDEYE MARAME SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100748 TOLOME CARLOS ADONIS BENIN INDEPENDANCE 102568 BA MAMADOU SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 101705 SEREME PACO BURKINA FASO INDEPENDANCE 250535 FALL IBRA MBACKE SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100117 NDIAYE IBRAHIMA DIAGO SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 251041 KEITA FANTA GOGO SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 101860 SADIO MAMADOU SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 250314 MANE MARIAMA SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 103715 BOLHO OUSMANE ROGER NIGER INDEPENDANCE 103628 TALL IBRAHIMA SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100812 NOUCHET FANNY J CATHERINE SENEGAL MERMOZ 104154 DIOP MAMADOU SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 100893 NUNEZ EVELYNE SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 101193 KODJO AHIA V ELEONORE COTE D'IVOIRE PARCELLES ASSAINIES 270003 FOUNE EL HADJI MALICK SENEGAL MERMOZ 105345 AMON ASSOUAN GNIMA EMMA J SENEGAL HLM 104728 KOUAKOU ABISSA CHRISTIAN SENEGAL PARCELLES ASSAINIES 270932 GBEDO MATHIEU BENIN INDEPENDANCE 200067 SAMBA ALASSANE SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 251359 DIOUF LOUIS CHEIKH SENEGAL TAMBACOUNDA 960262 BASSE PAPE SEYDOU SENEGAL ZI PARTICULIER 253433 OSENI SHERIFDEEN AKINDELE SENEGAL THIES 941039 SAKERA BOUBACAR FRANCE DIASPORA 230789 NDIAYE AISSATOU SENEGAL INDEPENDANCE 111336 NDIAYE AIDA EP MBAYE SENEGAL LAMINE GUEYE -

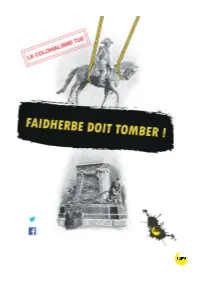

Statue Faidherbe

Une campagne à l’initiative de l’association Survie Nord à l’occasion du bicentenaire de la naissance de Louis Faidherbe le 3 juin 2018. En partenariat avec le Collectif Afrique, l’Atelier d’Histoire Critique, le Front uni des immigrations et des quartiers populaires (FUIQP), le Collectif sénégalais contre la célébration de Faidherbe . Consultez le site : faidherbedoittomber.org @ Abasfaidherbe Faidherbe doit tomber Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “père de l’impérialisme français” ? p. 4 Questions - réponses (à ceux qui veulent garder Faidherbe) p. 6 Qui était Louis Faidherbe ? p. 9 Un jeune Lillois sans éclat Un petit soldat de la conquête de l’Algérie Le factotum des affairistes Le « pacificateur » du Sénégal Un technicien du colonialisme Un idéologue raciste Une icône de la République coloniale Faidherbe vu du Sénégal p. 22 Aux origines lointaines de la Françafrique p. 29 Bibliographie p. 34 Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “ père de l’impérialisme français ” ? Depuis la fin du XIX e siècle, Lille et le nord de la France célèbrent perpétuellement la mémoire du gén éral Louis Faidherbe. Des rues et des lycées portent son nom. Des statues triomphales se dressent en son hommage au cœur de nos villes. Il y a là, pourtant, un scandale insup portable. Car Faidherbe était un colonialiste forcené. Il a massacré des milliers d’Africains au XIX e siècle. Il fut l’acteur clé de la conquête du Sénégal. Il défendit toute sa vie les théories racistes les plus abjectes. Si l’on considère que la colonisa tion est un crime contre l’humanité , il faut alors se rendre à l’évidence : celui que nos villes honorent quotidiennement est un criminel de haut rang. -

Liste Des Sous Agents Rapid Transfer

LISTE DES SOUS AGENTS RAPID TRANSFER DAKAR N° SOUS AGENTS VILLE ADRESSE 1 ETS GORA DIOP DAKAR 104 AV LAMINE GUEYE DAKAR 2 CPS CITÉ BCEAO DAKAR 111 RTE DE L'AÉROPORT CITE BCEAO2 COTE BOA 113 AVENUE BLAISE DIAGNE NON LOIN DE LA DIBITERIE ALLA SECK DU COTÉ 3 BBAS DAKAR OPPOSÉ 123 RUE MOUSSE DIOP (EX BLANCHOT) X FELIX FAURE PRES MOSQUEE 4 FOF BOUTIK DAKAR RAWANE MBAYE DAKAR PLATEAU 5 PAMECAS FASS PAILLOTTES DAKAR 2 VOIES FASS PARALLELE SN HLM, 200 M AVANT LE CASINO MEDINA 6 MAREGA VOYAGES DAKAR 32, RUE DE REIMS X MALICK SY 7 CPS OUEST FOIRE DAKAR 4 OUEST FOIRE RTE AÉROPORT FACE PHILIP MAGUILENE 8 CPS PIKINE SYNDICAT DAKAR 4449 TALY BOUBESS MARCHÉ SYNDICAT A COTE DU STADE ALASSANE DJIGO 9 TIMERA CHEIKHNA DAKAR 473 ARAFAT GRAND YOFF EN FACE COMMISSARIAT GRAND YOFF 5436 LIBERTÈ 5 NON LOIN DU ROND POINT JVC AVANT LA PHARMACIE MADIBA EN PARTANT DU ROND POINT JVC DIRECTION TOTAL LIBERTÉ 6 SUR 10 ERIC TCHALEU DAKAR LES 2 VOIES 5507 LIBERTÉ 5 EN FACE DERKLÉ ENTRE L'ECOLE KALIMA ET LA BOUTIQUE 11 SY JEAN CLEMENT DAKAR COSMETIKA 12 ETS SOW MOUHAMADOU SIRADJ DAKAR 7 RUE DE THIONG EN FACE DE L'ECOLE ADJA MAMA YACINE DIAGNE 13 TOPSA TRADE DAKAR 71 SOTRAC ANCIENNE PISTE EN FACE URGENCE CARDIO MERMOZ 14 DAFFA VOYAGE DAKAR 73 X 68 GUEULE TAPEE EN FACE DU LYCEE DELAFOSSE 15 ETS IDRISSA DIAGNE DAKAR 7765 BIS MERMOZ SICAP 16 MABOULA SERVICE DAKAR 7765 SICAP MERMOZ EN FACE AMBASSADE GABON 17 EST MAMADOU MAODO SOW DAKAR ALMADIE LOT°12 VILLA 084 DAKAR 18 DIEYE AISSATOU DAKAR ALMADIES 19 PAMECAS GRAND YOFF 1 DAKAR ARAFAT GRAND YOFF AVANT LA POLICE 2 20 CPS GUEDIAWAYE -

Market-Oriented Urban Agricultural Production in Dakar

CITY CASE STUDY DAKAR MARKET-ORIENTED URBAN AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION IN DAKAR Alain Mbaye and Paule Moustier 1. Introduction Occupying the Sahelian area of the tropical zone in a wide coastal strip (500 km along the Atlantic Ocean), Senegal covers some 196,192 km2 of gently undulating land. The climate is subtropical, with two seasons: the dry season lasting 9 months, from September to July, and the wet season from July to September. The Senegalese GNP (Gross National Product) of $570 per capita is above average for sub-Saharan Africa ($490). However, the economy is fragile and natural resources are limited. Services represent 60% of the GNP, and the rest is divided among agriculture and industry (World Bank 1996). In 1995, the total population of Senegal rose above 8,300,000 inhabitants. The urbanisation rate stands at 40%. Dakar represents half of the urban population of the region, and more than 20% of the total population. The other main cities are much smaller (Thiès: pop. 231,000; Kaolack: pop. 200000; St. Louis: pop. 160,000). Table 1: Basic facts about Senegal and Dakar Senegal Dakar (Urban Community) Area 196,192 km2 550 km2 Population (1995) 8,300,000 1,940,000 Growth rate 2,9% 4% Source: DPS 1995. The choice of Dakar as Senegal’s capital was due to its strategic location for marine shipping and its vicinity to a fertile agricultural region, the Niayes, so called for its stretches of fertile soil (Niayes), between parallel sand dunes. Since colonial times, the development of infrastructure and economic activity has been concentrated in Dakar and its surroundings. -

Museum Policies in Europe 1990 – 2010: Negotiating Professional and Political Utopia

Museum Policies in Europe 1990 – 2010: Negotiating Professional and Political Utopia Lill Eilertsen & Arne Bugge Amundsen (eds) EuNaMus Report No 3 Museum Policies in Europe 1990–2010: Negotiating Professional and Political Utopia (EuNaMus Report No. 3) Lill Eilertsen & Arne Bugge Amundsen (eds) Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. The online availability of the document implies permanent permission for anyone to read, to download, or to print out single copies for his/her own use and to use it unchanged for noncommercial research and educational purposes. Subsequent transfers of copyright cannot revoke this permission. All other uses of the document are conditional upon the consent of the copyright owner. The publisher has taken technical and administrative measures to assure authenticity, security and accessibility. According to intellectual property law, the author has the right to be mentioned when his/her work is accessed as described above and to be protected against infringement. For additional information about Linköping University Electronic Press and its procedures for publication and for assurance of document integrity, please refer to its www home page: http://www.ep.liu.se/. Linköping University Interdisciplinary Studies, No. 15 ISSN: 1650-9625 Linköping University Electronic Press Linköping, Sweden, 2012 URL: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-81315 Copyright © The Authors, 2012 This report has been published thanks to the support of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for Research - Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities theme (contract nr 244305 – Project European National Museums: Identity Politics, the Uses of the Past and the European Citizen). -

Dakar's Municipal Bond Issue: a Tale of Two Cities

Briefing Note 1603 May 2016 | Edward Paice Dakar’s municipal bond issue: A tale of two cities THE 19 MUNICIPALITIES OF THE CITY OF DAKAR Central and municipal governments are being overwhelmed by the rapid growth Cambérène Parcelles Assainies of Africa’s cities. Strategic planning has been insufficient and the provision of basic services to residents is worsening. Since the 1990s, widespread devolution has substantially shifted responsibility for coping with urbanisation to local Ngor Yoff Patte d’Oie authorities, yet municipal governments across Africa receive a paltry share of Grand-Yoff national income with which to discharge their responsibilities.1 Responsible and SICAP Dieuppeul-Derklé proactive city authorities are examining how to improve revenue generation and Liberté Ouakam HLM diversify their sources of finance. Municipal bonds may be a financing option for Mermoz Biscuiterie Sacré-Cœur Grand-Dakar some capital cities, depending on the legal and regulatory environment, investor appetite, and the creditworthiness of the borrower and proposed investment Fann-Point Hann-Bel-Air E-Amitié projects. This Briefing Note describes an attempt by the city of Dakar, the capital of Senegal, to launch the first municipal bond in the West African Economic and Gueule Tapée Fass-Colobane Monetary Union (WAEMU) area, and considers the ramifications of the central Médina Dakar-Plateau government blocking the initiative. Contested capital Sall also pressed for the adoption of an African Charter on Local Government and the establishment of an During the 2000s President Abdoulaye Wade sought African Union High Council on Local Authorities. For Sall, to establish Dakar as a major investment destination those closest to the people – local government – must and transform it into a “world-class” city. -

World War II at Sea This Page Intentionally Left Blank World War II at Sea

World War II at Sea This page intentionally left blank World War II at Sea AN ENCYCLOPEDIA Volume I: A–K Dr. Spencer C. Tucker Editor Dr. Paul G. Pierpaoli Jr. Associate Editor Dr. Eric W. Osborne Assistant Editor Vincent P. O’Hara Assistant Editor Copyright 2012 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World War II at sea : an encyclopedia / Spencer C. Tucker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-457-3 (hardcopy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-458-0 (ebook) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Naval operations— Encyclopedias. I. Tucker, Spencer, 1937– II. Title: World War Two at sea. D770.W66 2011 940.54'503—dc23 2011042142 ISBN: 978-1-59884-457-3 EISBN: 978-1-59884-458-0 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To Malcolm “Kip” Muir Jr., scholar, gifted teacher, and friend. This page intentionally left blank Contents About the Editor ix Editorial Advisory Board xi List of Entries xiii Preface xxiii Overview xxv Entries A–Z 1 Chronology of Principal Events of World War II at Sea 823 Glossary of World War II Naval Terms 831 Bibliography 839 List of Editors and Contributors 865 Categorical Index 877 Index 889 vii This page intentionally left blank About the Editor Spencer C. -

Senegal: Transport & Urban Mobility Project (P101415)

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results Report SENEGAL: TRANSPORT & URBAN MOBILITY PROJECT (P101415) SENEGAL: TRANSPORT & URBAN MOBILITY PROJECT (P101415) AFRICA | Senegal | Transport Global Practice | IBRD/IDA | Investment Project Financing | FY 2010 | Seq No: 17 | ARCHIVED on 23-Dec-2019 | ISR39922 | Public Disclosure Authorized Implementing Agencies: Agence des Travaux et de Gestion des Routes (AGEROUTE Senegal), Agence des Travaux et de Gestion des Routes (AGEROUTE Sénégal), Conseil Exécutif des Transports Urbains de Dakar (CETUD), Coordination du PATMUR, Ministere de l'Economie, des Finances et du PLan, Agence Autonome de Gestion des Routes (AGEROUTE ), Conseil Exécutif des Transports Urbains de Dakar (CETUD) Key Dates Key Project Dates Bank Approval Date: 01-Jun-2010 Effectiveness Date: 29-Dec-2010 Planned Mid Term Review Date: 01-Oct-2013 Actual Mid-Term Review Date: 31-Oct-2013 Original Closing Date: 30-Sep-2014 Revised Closing Date: 31-Dec-2019 Public Disclosure Authorized pdoTable Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The development objectives of this project are: (i) to improve effective road management and maintenance, both at national level and in urban areas; and (ii) to improve public urban transport in the Greater Dakar Area (GDA). Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project Objective? Yes Board Approved Revised Project Development Objective (If project is formally restructured) - Public Disclosure Authorized Components