Cultural Representations of Massacre Reinterpretations of the Mutiny of Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Gorée: Island of Memories

GOREE ISLAND OF MEMORIES GOREE ISLAND OF MEMORIES Unesco The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Unesco concerning the legal status of any country territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Published in 1985 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7 place de Fontenoy, 75700 Paris Printed by L. Vanmelle, Ghent, Belgium ISBN 92-3-102348-9 French edition 92-3-202348-2 © Unesco 1985 Printed in Belgium PREFACE Scarely have the lights of Dakar dimmed on the horizon than the launch puts in at the little harbour of Gorée. Half an hour has passed, just long enough for the sea-breeze to smooth away, as if by magic, the lines of fatigue from the faces of travellers Gorée, island of serenity, awaits us. And yet Gorée holds memories of the infamous trade that once condemned thousands of the sons and daughters of Africa if not to death, then to an exile from which none returned. The rays of the morning sun turn the facades to bronze. Each has its story to tell, confusing all sense of where we are ; in a single narrow street we pass a building, a courtyard, a stairway, a door or a set of architectural features that remind us of Amsterdam, Oporto, Seville, Saint Tropez, New Orleans, Nantes, Brooklyn and perhaps even Damascus. But if Gorée were merely a succession of architectural images, it would be but a stage set. -

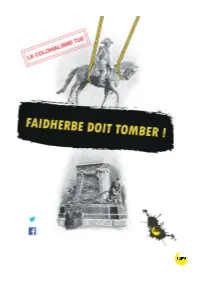

Statue Faidherbe

Une campagne à l’initiative de l’association Survie Nord à l’occasion du bicentenaire de la naissance de Louis Faidherbe le 3 juin 2018. En partenariat avec le Collectif Afrique, l’Atelier d’Histoire Critique, le Front uni des immigrations et des quartiers populaires (FUIQP), le Collectif sénégalais contre la célébration de Faidherbe . Consultez le site : faidherbedoittomber.org @ Abasfaidherbe Faidherbe doit tomber Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “père de l’impérialisme français” ? p. 4 Questions - réponses (à ceux qui veulent garder Faidherbe) p. 6 Qui était Louis Faidherbe ? p. 9 Un jeune Lillois sans éclat Un petit soldat de la conquête de l’Algérie Le factotum des affairistes Le « pacificateur » du Sénégal Un technicien du colonialisme Un idéologue raciste Une icône de la République coloniale Faidherbe vu du Sénégal p. 22 Aux origines lointaines de la Françafrique p. 29 Bibliographie p. 34 Faidherbe doit tomber ! Qui veut (encore) célébrer le “ père de l’impérialisme français ” ? Depuis la fin du XIX e siècle, Lille et le nord de la France célèbrent perpétuellement la mémoire du gén éral Louis Faidherbe. Des rues et des lycées portent son nom. Des statues triomphales se dressent en son hommage au cœur de nos villes. Il y a là, pourtant, un scandale insup portable. Car Faidherbe était un colonialiste forcené. Il a massacré des milliers d’Africains au XIX e siècle. Il fut l’acteur clé de la conquête du Sénégal. Il défendit toute sa vie les théories racistes les plus abjectes. Si l’on considère que la colonisa tion est un crime contre l’humanité , il faut alors se rendre à l’évidence : celui que nos villes honorent quotidiennement est un criminel de haut rang. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

February 2011

The Journal of Indian Education is a quarterly periodical published every year in May, August, November and February by the National Council of Educational Research and Training, New Delhi. The purpose is to provide a forum for teachers, teacher-educators, educational administrators and research workers; to encourage original and critical thinking in education through presentation of novel ideas, critical appraisals of contemporary educational problems and views and experiences on improved educational practices. The contents include thought-provoking articles by distinguished educationists, challenging discussions, analysis of educational issues and problems, book reviews and other features. Manuscripts along with computer soft copy, if any, sent in for publication should be exclusive to the Journal of Indian Education. These, along with the abstracts, should be in duplicate, typed double-spaced and on one side of the sheet only, addressed to the Academic Editor, Journal of Indian Education, Department of Teacher Education, NCERT, Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi 110 016. The Journal reviews educational publications other than textbooks. Publishers are invited to send two copies of their latest publications for review. Copyright of the articles published in the Journal will vest with the NCERT and no matter may be reproduced in any form without the prior permission of the NCERT. Academic Editor Raj Rani Editorial Committee Ranjana Arora Kiran Walia Yogesh Kumar Anupam Ahuja M.V. Srinivasan Lungthuiyang Riamei (JPF) Publication Team Head, Publication Division : Ashok Srivastava Chief Production Officer : Shiv Kumar Chief Editor (Incharge) : Naresh Yadav Chief Business Manager : Gautam Ganguly Assistant Editor : Hemant Kumar Assistant Production Officer : Abdul Naim Cover Amit Kumar Srivastava Single Copy : Rs. -

Indians As French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 Natasha Pairaudeau

Indians as French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 by Natasha Pairaudeau A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of London School of Oriental and African Studies Department of History June 2009 ProQuest Number: 10672932 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672932 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This study demonstrates how Indians with French citizenship were able through their stay in Indochina to have some say in shaping their position within the French colonial empire, and how in turn they made then' mark on Indochina itself. Known as ‘renouncers’, they gained their citizenship by renoimcing their personal laws in order to to be judged by the French civil code. Mainly residing in Cochinchina, they served primarily as functionaries in the French colonial administration, and spent the early decades of their stay battling to secure recognition of their electoral and civil rights in the colony. Their presence in Indochina in turn had an important influence on the ways in which the peoples of Indochina experienced and assessed French colonialism. -

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal –

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal – Key terms: Assimilation Association Direct rule Mission Dakar–Djibouti Direct Rule Direct rule is a system whereby the colonies were governed by European officials at the top position, then Natives were at the bottom. The Germans and French preferred this system of administration in their colonies. Reasons: This system enabled them to be harsh and use force to the African without any compromise, they used the direct rule in order to force African to produce raw materials and provide cheap labor The colonial powers did not like the use of chiefs because they saw them as backward and African people could not even know how to lead themselves in order to meet the colonial interests It was used to provide employment to the French and Germans, hence lowering unemployment rates in the home country Impacts of direct rule It undermined pre-existing African traditional rulers replacing them with others It managed to suppress African resistances since these colonies had enough white military forces to safeguard their interests This was done through the use of harsh and brutal means to make Africans meet the colonial demands. Assimilation (one ideological basis of French colonial policy in the 19th and 20th centuries) In contrast with British imperial policy, the French taught their subjects that, by adopting French language and culture, they could eventually become French and eventually turned them into black Frenchmen. The famous 'Four Communes' in Senegal were seen as proof of this. Here Africans were granted all the rights of French citizens. -

France, Africa, and the First World War Author(S): C

France, Africa, and the First World War Author(s): C. M. Andrew and A. S. Kanya-Forstner Source: The Journal of African History, Vol. 19, No. 1, World War I and Africa (1978), pp. 11-23 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/180609 . Accessed: 04/03/2014 05:38 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of African History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.158.158.60 on Tue, 4 Mar 2014 05:38:42 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Journal of African History, xix, i (1978), pp. 11-23 II Printed in Great Britain FRANCE, AFRICA, AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR BY C. M. ANDREW AND A. S. KANYA-FORSTNER BY 19I4 France possessed the largest Empire in African history. Yet that Empire was of only trivial interest to both French people and their govern- ments. As the diminutive colonialist movement complained: 'l'education coloniale des FranCaisdemeure entierement h faire'.1 Though few French- men suspected it in August I914, however, World War I was to mark a turning point in their relations with Africa in four ways. -

Final Report

P a g e | 1 Final Report Senegal: Floods in Dakar and Thiès DREF operation Operation n° MDRSN017 Date of Issue: 27 August 2021 Glide number: FL-2020-000198-SEN Operation start date: 12 September 2020 Operation end date: 31 March 2021 Host National Society: Operation budget: CHF 331,410 Number of people affected: 16,798 affected people Number of people assisted: 900 households (8,100 (5,879 men and 10,919 women) people) directly reached. Overall, 60,720 people (10,120) reached through awareness visits Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: IFRC, ICRC, Belgian and Spanish Red Cross Societies and the Turkish Red Crescent. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Civil Protection, Sanitation Directorate, and Territorial and Municipal Authorities The major donors and partners of the Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) include the Red Cross Societies and governments of Belgium, Britain, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Norway, Republic of Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland, as well as DG ECHO and Blizzard Entertainment, Mondelez International Foundation, and Fortive Corporation and other corporate and private donors. DG ECHO and the Canadian Government contributed to replenishing the DREF for this operation. On behalf of the Senegalese Red Cross Society (SRCS), the IFRC would like to extend gratitude to all for their generous contributions. <click here for the final financial report and here for contacts> A. SITUATION ANALYSIS Description of the disaster Senegal experienced heavy rainfall during the rainy season of 2020, exceeding the average amounts usually experienced during that period. -

Chapter 3: Dakar

DAKAR Capital cities 1.indd 31 9/22/11 4:20 PM DAKAR 3 Amadou Diop During the 20th century, the city of Dakar figured as the capital city of several territories, including countries such as Mali and Gambia. This attests to the central role it has played, and continues to play, in West Africa. Today, Dakar is firmly established as the capital of Senegal. A port city with a population of over 2.5 million and a location on a peninsula which continues to attract people from the country’s hinterland, Dakar has grown rapidly. It is administratively known as the Dakar Region, and comprises four départements (administrative districts) (see Figure 3.1) – Dakar, the original old city with a population of 1 million; Pikine, a large, sprawling department with a population of some 850 000; and Guédiawaye and Rufisque, two smaller departments of some 300 000 residents each (Diop 2008). The latter two represent the most recent peri-urban incorporation of settlements in the Dakar Region. Each of the four departments, in turn, comprise a number of communes, or smaller administrative units. This chapter is divided into two main parts. The first, ‘The urban geology of Dakar’, commences with a short history of the establishment and growth of the city, its economy and population. Subsequent sections discuss urban-planning activities before and after independence, government attempts through policy and practice to address the urban housing and urban transport challenges, and attempts to plan secondary commercial centres in the Dakar Region as more and more urban settlements are developed at some distance from the city centre of Dakar. -

A Historical Analysis of French and Senegal Cultural Relationship

FROM IMPERIALISM TO DIPLOMACY: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF FRENCH AND SENEGAL CULTURAL RELATIONSHIP BY AISHA BALARABE BAWA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY USMANU DANFODIYO UNIVERSITY, SOKOTO EMAIL:[email protected] Being a paper presented at the London Art as Cultural Diplomacy Conference 2013 on the theme: “Contemporary International Dialogue: Art-Based Developments and Culture shared between nations” Held at The Portcullis House, British Parliament from 21st to 24th August 2013. 1 Introduction France and Senegal shared a special relationship for over 300 years that date back to the 17th century. Saint- Louis was the first permanent French settlement in Senegal. Its geographical position meant that it commanded trade along the Senegal River. The four communes of Senegal (Goree, Dakar, Rufisque, and Saint- Louis) were the only place during the African colonial period, where African inhabitants were granted the same right as French. As the capital of French West Africa during the colonial period, Senegal was France‟s most important African territory. The French had a more concentrated and central presence there than in other colonies, so its culture became particularly ingrained into Senegalese life. The two countries have maintained the close ties since political independence. In spite Senegal obtaining it independence in 1960, it has maintained a positive relationship with France, and many elements of French culture introduced during the colonial period remain an important part of Senegalese identity. This paper examines the colonial language policy of French in Senegal as a form of cultural relationship between two nations. Overview of Literature Since the beginning of the 1960s, there have been a number of studies devoted in part or entirely to French colonial language policy in Africa. -

Compatriotism, Citizenship, and Catastrophe in French Martinique (1870 – 1902)

The Politics of Disaster in a Colony of Citizens: Compatriotism, Citizenship, and Catastrophe in French Martinique (1870 – 1902) By Christopher Michael Church A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Tyler Stovall, Chair Professor James P. Daughton Professor Thomas Laqueur Professor Percy Hintzen Spring 2014 The Politics of Disaster in a Colony of Citizens: Compatriotism, Citizenship, and Catastrophe in French Martinique (1870 – 1902) © Copyright 2014 Christopher Michael Church Abstract The Politics of Disaster in a Colony of Citizens: Compatriotism, Citizenship, and Catastrophe in French Martinique (1870 – 1902) By Christopher Michael Church Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Tyler Stovall, Chair As politicians of France’s Third Republic vied to build a democratic consensus and distance themselves from France’s recent autocratic past, they projected a fantasy of assimilation onto Martinique—one of France’s oldest colonies where the predominately non-white population had received full citizenship and universal manhood suffrage with the ratification of the Constitution of 1875. However, at the close of the nineteenth century, a series of disasters struck the French island of Martinique that threatened the republican fantasy of seamless assimilation: (1) the 1890 fire that destroyed the island’s capital of Fort-de-France; (2) the 1891 Atlantic hurricane that devastated the island’s economy and prompted a reevaluation of the place of the colony within the French nation; (3) the first general strike in 1900 wherein civil unrest in the colonies caused a political disaster in the metropole; and (4) the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée that killed over 30,000 people nearly instantaneously and cemented a postcolonial relationship characterized by dependence.