Marine Hybrids, the Lombardo Workshop and the Immaculate Virgin Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

Caterina Corner in Venetian History and Iconography Holly Hurlburt

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal 2009, vol. 4 Body of Empire: Caterina Corner in Venetian History and Iconography Holly Hurlburt n 1578, a committee of government officials and monk and historian IGirolamo Bardi planned a program of redecoration for the Sala del Maggior Consiglio (Great Council Hall) and the adjoining Scrutinio, among the largest and most important rooms in the Venetian Doge’s Palace. Completed, the schema would recount Venetian history in terms of its international stature, its victories, and particularly its conquests; by the sixteenth century Venice had created a sizable maritime empire that stretched across the eastern Mediterranean, to which it added considerable holdings on the Italian mainland.1 Yet what many Venetians regarded as the jewel of its empire, the island of Cyprus, was calamitously lost to the Ottoman Turks in 1571, three years before the first of two fires that would necessitate the redecoration of these civic spaces.2 Anxiety about such a loss, fear of future threats, concern for Venice’s place in evolving geopolitics, and nostalgia for the past prompted the creation of this triumphant pro- gram, which featured thirty-five historical scenes on the walls surmounted by a chronological series of ducal portraits. Complementing these were twenty-one large narratives on the ceiling, flanked by smaller depictions of the city’s feats spanning the previous seven hundred years. The program culminated in the Maggior Consiglio, with Tintoretto’s massive Paradise on one wall and, on the ceiling, three depictions of allegorical Venice in triumph by Tintoretto, Veronese, and Palma il Giovane. These rooms, a center of republican authority, became a showcase for the skills of these and other artists, whose history paintings in particular underscore the deeds of men: clothed, in armor, partially nude, frontal and foreshortened, 61 62 EMWJ 2009, vol. -

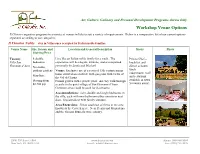

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

A Symbol of Global Protec- 7 1 5 4 5 10 10 17 5 4 8 4 7 1 1213 6 JAPAN 3 14 1 6 16 CHINA 33 2 6 18 AF Tion for the Heritage of All Humankind

4 T rom the vast plains of the Serengeti to historic cities such T 7 ICELAND as Vienna, Lima and Kyoto; from the prehistoric rock art 1 5 on the Iberian Peninsula to the Statue of Liberty; from the 2 8 Kasbah of Algiers to the Imperial Palace in Beijing — all 5 2 of these places, as varied as they are, have one thing in common. FINLAND O 3 All are World Heritage sites of outstanding cultural or natural 3 T 15 6 SWEDEN 13 4 value to humanity and are worthy of protection for future 1 5 1 1 14 T 24 NORWAY 11 2 20 generations to know and enjoy. 2 RUSSIAN 23 NIO M O UN IM D 1 R I 3 4 T A FEDERATION A L T • P 7 • W L 1 O 17 A 2 I 5 ESTONIA 6 R D L D N 7 O 7 H E M R 4 I E 3 T IN AG O 18 E • IM 8 PATR Key LATVIA 6 United Nations World 1 Cultural property The designations employed and the presentation 1 T Educational, Scientific and Heritage of material on this map do not imply the expres- 12 Cultural Organization Convention 1 Natural property 28 T sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of 14 10 1 1 22 DENMARK 9 LITHUANIA Mixed property (cultural and natural) 7 3 N UNESCO and National Geographic Society con- G 1 A UNITED 2 2 Transnational property cerning the legal status of any country, territory, 2 6 5 1 30 X BELARUS 1 city or area or of its authorities, or concerning 1 Property currently inscribed on the KINGDOM 4 1 the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171

EuFERRARcharistic MiraAcle of ITALY, 1171 This Eucharistic miracle took place in Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171. While celebrating Easter Mass, Father Pietro John Paul II pauses before the ceiling vault in Ferrara da Verona, the prior of the basilica, reached the moment of breaking the consecrated Church of Saint Mary in Vado, Ferrara Host when he saw blood gush from it and stain the ceiling Interior of the basilica vault above the altar with droplets. In 1595 the vault was enclosed within a small Bodini, The Miracle of the Blood. Painting on the ceiling shrine and is still visible today near the shrine in the monumental Basilica of Santa Maria in Vado. Detail of the ceiling vault stained with Blood Shrine that encloses the Holy Ceiling Vault (1594). The ceiling vault stained with Blood Right side of the cross n March 28, 1171, the prior of the Canons was rebuilt and expanded on the orders of Duke Miraculous Blood.” Even today, on the 28th day Regular Portuensi, Father Pietro da Verona, Ercole d’Este beginning in 1495. of every month in the basilica, which is currently was celebrating Easter Mass with three under the care of Saint Gaspare del Bufalo’s confreres (Bono, Leonardo and Aimone). At the regarding Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood, moment of the breaking of the consecrated Host, thisThere miracle. are Among many the mostsources important is the Eucharistic Adoration is celebrated in memory of It sprung forth a gush of Blood that threw large Bull of Pope Eugene IV (March 30, 1442), the miracle. -

“Safe from Destruction by Fire” Isabella Stewart Gardner’S Venetian Manuscripts

“Safe from Destruction by Fire” Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Venetian Manuscripts Anne- Marie Eze Houghton Library, Harvard University ver a decade ago the exhibition Gondola Days: Isabella Stewart Gardner and the Palazzo Barbaro Circle explored the rich Pan- OEuropean and American expatriate culture that fl ourished in Venice at the end of the nineteenth century and inspired Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924) to create a museum in Boston as a temple to Venetian art and architecture (fi g. 1). On this occasion, attention was drawn for the fi rst time to the museum’s holdings of Venetian manuscripts, and it was observed that in her day Gardner had been the only prominent American collector of manuscripts to focus on Venice.1 The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s collection of Venetian manuscripts comprises more than thirty items, spanning the fi eenth to eighteenth centuries. The collections can be divided into four broad categories: offi cial documents issued by the Doges; histories of the Most Serene Republic of Venice—called the “Sereni- ssima”—its government, and its patriciate; diplomas; and a statute book of 1 Helena Szépe, “Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Venetian Manuscripts,” in Gondola Days: Isa- bella Stewart Gardner and the Palazzo Barbaro Circle, ed. Elizabeth Anne McCauley, Alan Chong, Rosella Mamoli Zorzi, and Richard Lingner (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2004), 233–3⒌ 190 | Journal for Manuscript Studies Figure 1. Veronese Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. a lay con aternity.2 Most of the manuscripts contain complete and dated texts, are illuminated, and survive in their original bindings. The Gardner’s collection not only charts the evolution over three centuries of Venetian book production, but also provides a wealth of sources for the study of the history, portraiture, iconography, genealogy, and heraldry of the Republic of Venice. -

Verona Featuring Venice and the Italian Lakes

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of LAND 24 Travele rs JO URNEY Verona featuring Venice and the Italian Lakes Inspiring Moments > Embrace the romantic ambience of Verona, where Romeo and Juliet fell in love, brimming with pretty piazzas, quiet parks and a Roman arena. > Wander through the warren of narrow INCLUDED FEATURES streets and bridges that cross the canals of Venice. Accommodations (with baggage handling) Itinerary > Dine on classic cuisine and sip the – 7 nights in Verona, Italy, at the Day 1 Depart gateway city Veneto’s renowned wines as you first-class Hotel Indigo Verona – Day 2 Arrive in Verona and transfer enjoy a homemade meal. Grand Hotel des Arts. to hotel. > Cruise Lake Garda and experience the Extensive Meal Program Day 3 Verona chic Italian lakes lifestyle. – 7 breakfasts, 3 lunches and 3 dinners, Day 4 Lake Garda | Valpolicella Winery > Admire Palladio’s architectural including Welcome and Farewell Dinners; Day 5 Venice genius in Vicenza . tea or coffee with all meals, plus wine Day 6 Verona > Experience three UNESCO World with dinner. Day 7 Bassano del Grappa | Vicenza Heritage sites. – Opportunities to sample authentic cuisine and local flavors Day 8 Padua | Verona Day 9 Transfer to airport and depart Scenic Lago di Garda Your One-of-a-Kind Journey for gateway city – Discovery excursions highlight the local culture, heritage and history. Flights and transfers included for AHI FlexAir participants. – Expert-led Enrichment programs Note: Itinerary may change due to local conditions. enhance your insight into the region. Activity Level: We have rated all of our excursions with activity levels to help you assess this program’s physical – AHI Sustainability Promise: expectations. -

VENICE Grant Allen's Historical Guides

GR KS ^.At ENICE W VENICE Grant Allen's Historical Guides // is proposed to issue the Guides of this Series in the following order :— Paris, Florence, Cities of Belgium, Venice, Munich, Cities of North Italy (Milan, Verona, Padua, Bologna, Ravenna), Dresden (with Nuremberg, etc.), Rome (Pagan and Christian), Cities of Northern France (Rouen, Amiens, Blois, Tours, Orleans). The following arc now ready:— PARIS. FLORENCE. CITIES OF BELGIUM. VENICE. Fcap. 8vo, price 3s. 6d. each net. Bound in Green Cloth with rounded corners to slip into the pocket. THE TIMES.—" Good work in the way of showing students the right manner of approaching the history of a great city. These useful little volumes." THE SCOTSMAN "Those who travel for the sake of culture will be well catered for in Mr. Grant Allen's new series of historical guides. There are few more satisfactory books for a student who wishes to dig out the Paris of the past from the im- mense superincumbent mass of coffee-houses, kiosks, fashionable hotels, and other temples of civilisation, beneath which it is now submerged. Florence is more easily dug up, as you have only to go into the picture galleries, or into the churches or museums, whither Mr. Allen's^ guide accordingly conducts you, and tells you what to look at if you want to understand the art treasures of the city. The books, in a word, explain rather than describe. Such books are wanted nowadays. The more sober- minded among tourists will be grateful to him for the skill with which the new series promises to minister to their needs." GRANT RICHARDS 9 Henrietta St. -

Norberto Gramaccini Petrucci, Manutius Und Campagnola Die Medialisierung Der Künste Um 1500

Norberto Gramaccini Petrucci, Manutius und Campagnola Die Medialisierungder Künste um 1500 Die Jahre um 1500 waren für die Medialisierung der Künste und Wissenschaften von entscheidender Bedeutung.1 Am 15.Mai 1501 brachte in Venedig der aus Fossombrone gebürtige Musikdrucker Ottaviano dei Petrucci (1466–1539) mitseinemmusikalischen BeraterPetrusCastellanus das Harmonicemusices OdhecatonA(RISM 15011)heraus: Es ist das erste im Typendruckverfahren hergestellte Buch in mehrstimmigen Mensuralnoten, enthaltend 100drei- und vierstimmige Chansons der bekanntesten zeitgenössischen Komponisten –die meisten Franzosen und Flamen.2 Bereits 1498 hatte Petrucci beim veneziani- schen Senat ein Gesuch gestellt, das ihm als Erfnder ein Monopol für die Dauer von 20 Jahren zusichern sollte: »… chome aprimo Inventore che niuno altro nel dominio de Vostra Signoria possi stampare Canto fgurado …per anni vinti«.3 Dem Erstling folgten gleichgeartete Publikationen (Canti B, Canti C), die ei- nen Hinweis liefern, dass Petruccis vorrangiges Ziel in den ersten Jahren sei- ner Herausgebertätigkeit (bis 1504)darin bestand, nicht die sakrale, sondern 1Hans Blumenberg, Die Lesbarkeit der Welt,Frankfurt 1983;David McKitterick, Print, Manuscript and the Search for Order, 1450–1830,Cambridge 2004,S.109. 2Helen Hewitt und Isabel Pope, Petrucci. Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A,New York 1978. Das Datum 15/V/1501geht aus der Widmung an Girolamo Donato hervor. Für eine andere Datierung, David Fallows, »Petrucci’s Canti Volumes: Scope and Repertory«, in: Basler Jahrbuch für Historische Musikpraxis 25: Musik –Druck –Musikdruck. 500Jahre Ottaviano Petrucci (2001), S.39–52: S.41.ZuCastellanus,dem »magistercapelle«der Kirche SS.Giovanni ePaolo, den die Zeitgenossen als »arte musice monarcha« bezeichneten, Bonnie J. Blackburn, »Petrucci’s Venetian Editor: Petrus Castellanus and His Musical Garden«, in: Musica Disciplina 40 (1995), S.15–41: S.25.Zuden späten Quellen, die Petrucci auch als Besitzer mehrerer Papiermühlen ausweisen, Teresa M. -

Sebastiano Del Piombo and His Collaboration with Michelangelo: Distance and Proximity to the Divine in Catholic Reformation Rome

SEBASTIANO DEL PIOMBO AND HIS COLLABORATION WITH MICHELANGELO: DISTANCE AND PROXIMITY TO THE DIVINE IN CATHOLIC REFORMATION ROME by Marsha Libina A dissertation submitted to the Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland April, 2015 © 2015 Marsha Libina All Rights Reserved Abstract This dissertation is structured around seven paintings that mark decisive moments in Sebastiano del Piombo’s Roman career (1511-47) and his collaboration with Michelangelo. Scholarship on Sebastiano’s collaborative works with Michelangelo typically concentrates on the artists’ division of labor and explains the works as a reconciliation of Venetian colorito (coloring) and Tuscan disegno (design). Consequently, discourses of interregional rivalry, center and periphery, and the normativity of the Roman High Renaissance become the overriding terms in which Sebastiano’s work is discussed. What has been overlooked is Sebastiano’s own visual intelligence, his active rather than passive use of Michelangelo’s skills, and the novelty of his works, made in response to reform currents of the early sixteenth century. This study investigates the significance behind Sebastiano’s repeating, slowing down, and narrowing in on the figure of Christ in his Roman works. The dissertation begins by addressing Sebastiano’s use of Michelangelo’s drawings as catalysts for his own inventions, demonstrating his investment in collaboration and strategies of citation as tools for artistic image-making. Focusing on Sebastiano’s reinvention of his partner’s drawings, it then looks at the ways in which the artist engaged with the central debates of the Catholic Reformation – debates on the Church’s mediation of the divine, the role of the individual in the path to personal salvation, and the increasingly problematic distance between the layperson and God. -

Patrician Lawyers in Quattrocento Venice

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Servants of the Republic: Patrician lawyers in Quattrocento Venice. Jones, Scott Lee How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Jones, Scott Lee (2010) Servants of the Republic: Patrician lawyers in Quattrocento Venice.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42517 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Swansea University Prifysgol Abertawe Servants of the Republic: Patrician Lawyers inQuattrocento Venice Scott Lee Jones Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2010 ProQuest Number: 10805266 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted.