9. Chapter 2 Negotiation the Wedding in Naples 96–137 DB2622012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

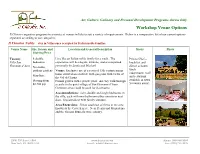

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171

EuFERRARcharistic MiraAcle of ITALY, 1171 This Eucharistic miracle took place in Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171. While celebrating Easter Mass, Father Pietro John Paul II pauses before the ceiling vault in Ferrara da Verona, the prior of the basilica, reached the moment of breaking the consecrated Church of Saint Mary in Vado, Ferrara Host when he saw blood gush from it and stain the ceiling Interior of the basilica vault above the altar with droplets. In 1595 the vault was enclosed within a small Bodini, The Miracle of the Blood. Painting on the ceiling shrine and is still visible today near the shrine in the monumental Basilica of Santa Maria in Vado. Detail of the ceiling vault stained with Blood Shrine that encloses the Holy Ceiling Vault (1594). The ceiling vault stained with Blood Right side of the cross n March 28, 1171, the prior of the Canons was rebuilt and expanded on the orders of Duke Miraculous Blood.” Even today, on the 28th day Regular Portuensi, Father Pietro da Verona, Ercole d’Este beginning in 1495. of every month in the basilica, which is currently was celebrating Easter Mass with three under the care of Saint Gaspare del Bufalo’s confreres (Bono, Leonardo and Aimone). At the regarding Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood, moment of the breaking of the consecrated Host, thisThere miracle. are Among many the mostsources important is the Eucharistic Adoration is celebrated in memory of It sprung forth a gush of Blood that threw large Bull of Pope Eugene IV (March 30, 1442), the miracle. -

Borso D'este, Venice, and Pope Paul II

I quaderni del m.æ.s. – XVIII / 2020 «Bon fiol di questo stado» Borso d’Este, Venice, and pope Paul II: explaining success in Renaissance Italian politics Richard M. Tristano Abstract: Despite Giuseppe Pardi’s judgment that Borso d’Este lacked the ability to connect single parts of statecraft into a stable foundation, this study suggests that Borso conducted a coherent and successful foreign policy of peace, heightened prestige, and greater freedom to dispose. As a result, he was an active participant in the Quattrocento state system (Grande Politico Quadro) solidified by the Peace of Lodi (1454), and one of the most successful rulers of a smaller principality among stronger competitive states. He conducted his foreign policy based on four foundational principles. The first was stability. Borso anchored his statecraft by aligning Ferrara with Venice and the papacy. The second was display or the politics of splendor. The third was development of stored knowledge, based on the reputation and antiquity of Estense rule, both worldly and religious. The fourth was the politics of personality, based on Borso’s affability, popularity, and other virtues. The culmination of Borso’s successful statecraft was his investiture as Duke of Ferrara by Pope Paul II. His success contrasted with the disaster of the War of Ferrara, when Ercole I abandoned Borso’s formula for rule. Ultimately, the memory of Borso’s successful reputation was preserved for more than a century. Borso d’Este; Ferrara; Foreign policy; Venice; Pope Paul II ISSN 2533-2325 doi: 10.6092/issn.2533-2325/11827 I quaderni del m.æ.s. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Benedetto Reguardati of Nursia (1398-1469)

BENEDETTO REGUARDATI OF NURSIA (1398-1469) by JULIANA HILL COTTON BENEDETrO REGUARDATI was a physician and a diplomat.' His medical skill, shared by his younger son, Dionisio, was an inherited calling, for he came from the stock of the Norcini, medicine men, renowned throughout the ages for traditional skill in magic and healing. In his own lifetime Reguardati is said to have 'greatly increased the glory of his family' acquired in the past by his ancestors in the city of Nursia' (ac domus sue splendorem quem in Nurisina civitate vetustis temporibus comparatum a suis maioribus, ipse plurimum auxit, Cicco Simonetta, 1 September 1464). He himself bore the proud name ofhis more famous compaesano, St. Benedict ofNursia (480-543), whose mother had been Abbondanza Reguardati. Reguardati's diplomatic career deserves consideration in any detailed study of Renaissance diplomacy, a neglected field to which the late Garrett Mattingly has drawn attention. To the Reguardati family this also was a traditional vocation. Benedetto's brother, Marino, his son Carlo, both lawyers, became Roman Senators. Carlo served the court of Milan at Urbino (M.A.P. IX, 276, 14 March 1462)2 and at Pesaro. He was at Florence when Benedetto died there in 1469. Another diplomat, Giovanni Reguardati, described by Professor Babinger as 'Venetian' ambassador to Ladislaus, King of Hungary in 1444,3 was probably a kinsman, one of the many Norcini in the pay of Venice. Francesco Filelfo (1398-1481) in a letter to Niccolo Ceba, dated 26 February 1450, recalls that Benedetto Reguardati -

Ferrara Venice Milan Mantua Cremona Pavia Verona Padua

Milan Verona Venice Cremona Padua Pavia Mantua Genoa Ferrara Bologna Florence Urbino Rome Naples Map of Italy indicating, in light type, cities mentioned in the exhibition. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust Court Artists Artists at court were frequently kept on retainer by their patrons, receiving a regular salary in return for undertaking a variety of projects. Their privileged position eliminated the need to actively seek customers, granting them time and artistic freedom to experiment with new materials and techniques, subject matter, and styles. Court artists could be held in high regard not only for their talents as painters or illuminators but also for their learning, wit, and manners. Some artists maintained their elevated positions for decades. Their frequent movements among the Italian courts could depend on summons from wealthier patrons or dismissals if their style was outmoded. Consequently their innovations— among the most significant in the history of Renaissance art—spread quickly throughout the peninsula. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust Court Patrons Social standing, religious rank, piety, wealth, and artistic taste were factors that influenced the ability and desire of patrons to commission art for themselves and for others. Frequently a patron’s portrait, coat of arms, or personal emblems were prominently displayed in illuminated manuscripts, which could include prayer books, manuals concerning moral conduct, humanist texts for scholarly learning, and liturgical manuscripts for Christian worship. Patrons sometimes worked closely with artists to determine the visual content of a manuscript commission and to ensure the refinement and beauty of the overall decorative scheme. -

Levitsky Dissertation

The Song from the Singer: Personification, Embodiment, and Anthropomorphization in Troubadour Lyric Anne Levitsky Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Anne Levitsky All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Song from the Singer: Personification, Embodiment, and Anthropomorphization in Troubadour Lyric Anne Levitsky This dissertation explores the relationship of the act of singing to being a human in the lyric poetry of the troubadours, traveling poet-musicians who frequented the courts of contemporary southern France in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. In my dissertation, I demonstrate that the troubadours surpass traditionally-held perceptions of their corpus as one entirely engaged with themes of courtly romance and society, and argue that their lyric poetry instead both displays the influence of philosophical conceptions of sound, and critiques notions of personhood and sexuality privileged by grammarians, philosophers, and theologians. I examine a poetic device within troubadour songs that I term ‘personified song’—an occurrence in the lyric tradition where a performer turns toward the song he/she is about to finish singing and directly addresses it. This act lends the song the human capabilities of speech, motion, and agency. It is through the lens of the ‘personified song’ that I analyze this understudied facet of troubadour song. Chapter One argues that the location of personification in the poetic text interacts with the song’s melodic structure to affect the type of personification the song undergoes, while exploring the ways in which singing facilitates the creation of a body for the song. -

On the Art of Fighting: a Humanist Translation of Fiore Dei Liberi's

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Scholarly section, articles 99 On the Art of Fighting: A Humanist Translation of Fiore dei Liberi’s Flower of Battle Owned by Leonello D’Este Ken Mondschein Anna Maria College / Goodwin College / Massachussets historical swordmanship Abstract – The author presents a study of Bibliothèque National de France MS Latin 11269, a manuscript that he argues was associated with the court of Leonello d’Este and which represents an attempt to “fix” or “canonize” a vernacular work on a practical subject in erudite Latin poetry. The author reviews the life of Fiore dei Liberi and Leonello d’Este and discusses the author’s intentions in writing, how the manuscript shows clear signs of Estense associations, and examines the manuscript both in light of its codicological context and in light of humanist activity at the Estense court. He also presents the evidence for the book having been in the Estense library. Finally, he examines the place of the manuscript in the context of the later Italian tradition of fencing books. A complete concordance is presented in the appendix. Keywords – Leonello d’Este, humanism, Fiore dei Liberi, Latin literature, Renaissance humanism, translation I. INTRODUCTION The Flower of Battle (Flos Duellatorum in Latin or Fior di Battaglia in Italian) of Fiore dei Liberi (c. 1350—before 1425) comes down to us in four manuscripts: Getty MS Ludwig XV 13; Morgan Library M.383; a copy privately held by the Pisani-Dossi family; and Bibliothèque National de France MS Latin 11269.1 Another Fiore manuscript attested in 1 The Pisani-Dossi was published by Novati as Flos duellatorum: Il Fior di battaglia di maestro Fiore dei Liberi da Premariacco, and republished by Nostini in 1982 and Rapisardi as Flos Duellatorum in armis, sine armis, equester et pedester. -

Le Signorie Dei Rossi Di Parma Tra XIV E XVI Secolo

Le signorie dei Rossi di Parma tra XIV e XVI secolo a cura di Letizia Arcangeli e Marco Gentile Firenze University Press 2007 Le signorie dei Rossi di Parma tra XIV e XVI secolo / a cura di Letizia Arcangeli e Marco Gentile. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2007. (Reti medievali E-book. Quaderni ; 6) ISBN (print) 978-88-8453- 683-9 ISBN (online) 978-88-8453- 684-6 945.44 © 2007 Firenze University Press Università degli Studi di Firenze Firenze University Press Borgo Albizi, 28 50122 Firenze, Italy http://epress.unifi.it/ Printed in Italy Indice Letizia Arcangeli e Marco Gentile, Premessa 7 Abbreviazioni 13 Gabriele Nori, «Nei ripostigli delle scanzie». L’archivio dei Rossi di San Secondo 15 Marco Gentile, La formazione del dominio dei Rossi tra XIV e XV secolo 23 Nadia Covini, Le condotte dei Rossi di Parma. Tra conflitti interstatali e «picciole guerre» locali (1447-1482) 57 Gianluca Battioni, Aspetti della politica ecclesiastica di Pier Maria Rossi 101 Francesco Somaini, Una storia spezzata: la carriera ecclesiastica di Bernardo Rossi tra il «piccolo Stato», la corte sforzesca, la curia romana e il «sistema degli Stati italiani» 109 Giuseppa Z. Zanichelli, La committenza dei Rossi: immagini di potere fra sacro e profano 187 Antonia Tissoni Benvenuti, Libri e letterati nelle piccole corti padane del Rinascimento. La corte di Pietro Maria Rossi 213 Letizia Arcangeli, Principi, homines e «partesani» nel ritorno dei Rossi 231 Indice onomastico e toponomastico 307 L. Arcangeli, M. Gentile (a cura di), Le signorie dei Rossi di Parma tra XIV e XVI secolo, ISBN (print) 978-88-8453- 683-9, ISBN (online) 978-88-8453- 684-6, © 2007 Firenze University Press. -

Franca Leverotti

Franca Leverotti Gli officiali del ducato sforzesco [A stampa in “Annali della Classe di Lettere e Filosofia della Scuola Normale Superiore”, serie IV, Quaderni I (1997), pp. 17-77 – Distribuito in formato digitale da “Reti Medievali”] Una breve risposta al questionario Modi di nomina degli officiali È il duca che decide in ultima istanza i nomi degli officiali, anche se la scelta è teoricamente condizionata dall’approvazione della maggioranza dei consiglieri segreti e di giustizia allo scopo – così esplicitato “adeo quod officiis de personis idoneis provideatur, non autem personis de officiis” – di avere personale competente e idoneo. La scelta dei sindacatori e degli officiali periferici (podestà, capitani...) in particolare rimane per tutto il periodo sforzesco di competenza del Consiglio Segreto, così come nel caso di uffici venduti, o, più esattamente, di uffici concessi dietro un prestito (prestito che veniva restituito alla fine del mandato, non dal duca, ma dall’ufficiale che subentrava); prerequisito per la nomina in questi casi era infatti non soltanto il versamento della somma alle magistrature finanziarie, ma la valutazione del curriculum da parte del Consiglio Segreto, oltre all’attestazione che era stato assolto dai sindacatori per i precedenti incarichi. Nel caso di “novus officialis “ il Consiglio, prima di procedere alla nomina, doveva richiedere il parere di tre persone note, in genere esponenti di spicco della società milanese, cortigiani o burocrati, che vengono nominati nella nota di trasmissione al primo segretario Cicco Simonetta, il cui benestare era essenziale per perfezionare l’iter della pratica. Carriere Non c’è commistione tra uffici centrali e periferici. Si tratta di circuiti ben distinti che non hanno interferenze tra loro tranne poche eccezioni: i vicari promossi sindacatori generali hanno alle spalle una carriera di vicari di podestà cittadini e di podestà, mentre i referendari delle città possono diventare maestri delle entrate. -

Antonio Pistoia: the Poetic World of a Customs Collector

Valentina Olivastri ANTONIO PISTOIA: THE POETIC WORLD OF A CUSTOMS COLLECTOR A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London, University of London Supervisors of Research: Anna Laura Lepschy, Giovanni Aquilecchia September 1999 ProQuest Number: U641904 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U641904 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract The object of the present study is Antonio Pistoia (1436?- 1502); a jocular poet and customs collector who worked mainly in Northern Italy. Although his reputation as a notable literary figure has suffered from neglect in recent times, his work was appreciated by and known to his contemporaries including Pietro Aretino, Ludovico Ariosto, Matteo Bandello, Francesco Berni and Baldesar Castiglione. Research on his life and work came to a halt at the beginning of this century and since then he has failed to attract significant attention. The present study attempts to review and re-examine both the man and his work with a view to putting Antonio Pistoia back on the literary map.