Borso D'este, Venice, and Pope Paul II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

Staff Working Paper No. 845 Eight Centuries of Global Real Interest Rates, R-G, and the ‘Suprasecular’ Decline, 1311–2018 Paul Schmelzing

CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 -

Jews on Trial: the Papal Inquisition in Modena

1 Jews, Papal Inquisitors and the Estense dukes In 1598, the year that Duke Cesare d’Este (1562–1628) lost Ferrara to Papal forces and moved the capital of his duchy to Modena, the Papal Inquisition in Modena was elevated from vicariate to full Inquisitorial status. Despite initial clashes with the Duke, the Inquisition began to prosecute not only heretics and blasphemers, but also professing Jews. Such a policy towards infidels by an organization appointed to enquire into heresy (inquisitio haereticae pravitatis) was unusual. In order to understand this process this chapter studies the political situation in Modena, the socio-religious predicament of Modenese Jews, how the Roman Inquisition in Modena was established despite ducal restrictions and finally the steps taken by the Holy Office to gain jurisdiction over professing Jews. It argues that in Modena, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Holy Office, directly empowered by popes to try Jews who violated canons, was taking unprecedented judicial actions against them. Modena, a small city on the south side of the Po Valley, seventy miles west of Ferrara in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, originated as the Roman town of Mutina, but after centuries of destruction and renewal it evolved as a market town and as a busy commercial centre of a fertile countryside. It was built around a Romanesque cathedral and the Ghirlandina tower, intersected by canals and cut through by the Via Aemilia, the ancient Roman highway from Piacenza to Rimini. It was part of the duchy ruled by the Este family, who origi- nated in Este, to the south of the Euganean hills, and the territories it ruled at their greatest extent stretched from the Adriatic coast across the Po Valley and up into the Apennines beyond Modena and Reggio, as well as north of the Po into the Polesine region. -

Charles V, Monarchia Universalis and the Law of Nations (1515-1530)

+(,121/,1( Citation: 71 Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis 79 2003 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Mon Jan 30 03:58:51 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information CHARLES V, MONARCHIA UNIVERSALIS AND THE LAW OF NATIONS (1515-1530) by RANDALL LESAFFER (Tilburg and Leuven)* Introduction Nowadays most international legal historians agree that the first half of the sixteenth century - coinciding with the life of the emperor Charles V (1500- 1558) - marked the collapse of the medieval European order and the very first origins of the modem state system'. Though it took to the end of the seven- teenth century for the modem law of nations, based on the idea of state sover- eignty, to be formed, the roots of many of its concepts and institutions can be situated in this period2 . While all this might be true in retrospect, it would be by far overstretching the point to state that the victory of the emerging sovereign state over the medieval system was a foregone conclusion for the politicians and lawyers of * I am greatly indebted to professor James Crawford (Cambridge), professor Karl- Heinz Ziegler (Hamburg) and Mrs. Norah Engmann-Gallagher for their comments and suggestions, as well as to the board and staff of the Lauterpacht Research Centre for Inter- national Law at the University of Cambridge for their hospitality during the period I worked there on this article. -

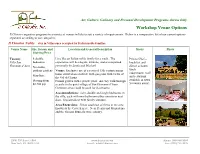

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171

EuFERRARcharistic MiraAcle of ITALY, 1171 This Eucharistic miracle took place in Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171. While celebrating Easter Mass, Father Pietro John Paul II pauses before the ceiling vault in Ferrara da Verona, the prior of the basilica, reached the moment of breaking the consecrated Church of Saint Mary in Vado, Ferrara Host when he saw blood gush from it and stain the ceiling Interior of the basilica vault above the altar with droplets. In 1595 the vault was enclosed within a small Bodini, The Miracle of the Blood. Painting on the ceiling shrine and is still visible today near the shrine in the monumental Basilica of Santa Maria in Vado. Detail of the ceiling vault stained with Blood Shrine that encloses the Holy Ceiling Vault (1594). The ceiling vault stained with Blood Right side of the cross n March 28, 1171, the prior of the Canons was rebuilt and expanded on the orders of Duke Miraculous Blood.” Even today, on the 28th day Regular Portuensi, Father Pietro da Verona, Ercole d’Este beginning in 1495. of every month in the basilica, which is currently was celebrating Easter Mass with three under the care of Saint Gaspare del Bufalo’s confreres (Bono, Leonardo and Aimone). At the regarding Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood, moment of the breaking of the consecrated Host, thisThere miracle. are Among many the mostsources important is the Eucharistic Adoration is celebrated in memory of It sprung forth a gush of Blood that threw large Bull of Pope Eugene IV (March 30, 1442), the miracle. -

Fra Sabba Da Castiglione: the Self-Fashioning of a Renaissance Knight Hospitaller”

“Fra Sabba da Castiglione: The Self-Fashioning of a Renaissance Knight Hospitaller” by Ranieri Moore Cavaceppi B.A., University of Pennsylvania 1988 M.A., University of North Carolina 1996 Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Italian Studies at Brown University May 2011 © Copyright 2011 by Ranieri Moore Cavaceppi This dissertation by Ranieri Moore Cavaceppi is accepted in its present form by the Department of Italian Studies as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Ronald L. Martinez, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date Evelyn Lincoln, Reader Date Ennio Rao, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date Peter M. Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Ranieri Moore Cavaceppi was born in Rome, Italy on October 11, 1965, and moved to Washington, DC at the age of ten. A Fulbright Fellow and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Ranieri received an M.A. in Italian literature from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1996, whereupon he began his doctoral studies at Brown University with an emphasis on medieval and Renaissance Italian literature. Returning home to Washington in the fall of 2000, Ranieri became the father of three children, commenced his dissertation research on Knights Hospitaller, and was appointed the primary full-time instructor at American University, acting as language coordinator for the Italian program. iv PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I deeply appreciate the generous help that I received from each member of my dissertation committee: my advisor Ronald Martinez took a keen interest in this project since its inception in 2004 and suggested many of its leading insights; my readers Evelyn Lincoln and Ennio Rao contributed numerous observations and suggestions. -

11 the Ciompi Revolt of 1378

The Ciompi Revolt of 1378: Socio-Political Constraints and Economic Demands of Workers in Renaissance Florence Alex Kitchel I. Introduction In June of 1378, political tensions between the Parte Guelpha (supporters of the Papacy) and the Ghibellines (supporters of the Holy Roman Emperor) were on the rise in Italy. These tensions stemmed from the Parte Guelpha’s use of proscriptions (either a death sentence or banishment/exile) and admonitions (denying one’s eligibility for magisterial office) to rid Ghibellines (and whomever else they wanted for whatever reasons) from participation in the government. However, the Guelphs had been unable to prevent their Ghibelline adversary, Salvestro de’ Medici, from obtaining the position of Gonfaloniere (“Standard-Bearer of Justice”), the most powerful position in the commune. By proposing an ultimately unsuccessful renewal of the anti-magnate Law of Ordinances, he was able to win the support of the popolo minuto (“little people”), who, at his bidding, ran around the city, burning and looting the houses of the Guelphs. By targeting specific families and also by allying themselves with the minor guilds, these “working poor” hoped to force negotiations for socio-economic and political reform upon the major-guildsmen. Instead, however, this forced the creation of a balìa (an oligarchic ruling committee of patricians), charged with suppressing the rioting throughout the city. With the city still high-strung, yet more rioting broke out in the following month. The few days before July 21, 1378 were shrouded in conspiracy and plotting. Fearing that the popolo minuto were holding secret meetings all throughout the city, the government arrested some of their leaders, and, under torture, these “little people” confessed to plans of creating three new guilds and eliminating forced loan policies. -

Fortune and Romance : Boiardo in America / Edited by Jo Ann Cavallo & Charles S

Fortune and Romance: Boiardo in America xexTS & STuOies Volume 183 Fortune and Romance Boiardo in America edited b)' Jo Ann Cavallo & Charles Ross cr)eC>iev2iL & ReMAissAMce tgxts & STuDies Tempe, Arizona 1998 The three plates that appear following page 60 are reproduced by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library. The map of Georgia that appears on page 95 is reprinted from David Braund's Georgia in Antiquity (Oxford University Press, 1994), by permission of Oxford University Press. Figures 8, 10 and 11 are reprinted courtesy of Alinari/Art Resource, New York. Figure 9 is reprinted courtesy of Scala, Art Resource, New York. ©Copyright 1998 The Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America at Columbia University Library of Congress Cataloging'in'Publication Data Fortune and romance : Boiardo in America / edited by Jo Ann Cavallo & Charles S. Ross p. cm. — (Medieval & Renaissance texts & studies ; 183) Most of the essays in this volume stem from the American Boiardo Quincentennial Conference, "Boiardo 1994 in America," held in Butler Library, Columbia University, Oct. 7-9, 1994, sponsored by the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-86698-225-6 (alk. paper) 1. Boiardo, Matteo Maria, 1440 or 41-1494 — Criticism and interpreta- tion — Congresses. 1. Cavallo, Jo Ann. II. Ross, Charles Stanley. III. American Boiardo Quincentennial Conference "Boairdo 1994 in America" (1994 : Butler Library, Columbia University) IV. Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America. V. Series. PQ4614.F67 1998 85r.2— dc21 98-11569 CIP @ This book is made to last. It is set in Goudy, smyth-sewn, and printed on acid-free paper to library specifications. -

9. Chapter 2 Negotiation the Wedding in Naples 96–137 DB2622012

Chapter 2 Negotiation: The Wedding in Naples On 1 November 1472, at the Castelnuovo in Naples, the contract for the marriage per verba de presenti of Eleonora d’Aragona and Ercole d’Este was signed on their behalf by Ferrante and Ugolotto Facino.1 The bride and groom’s agreement to the marriage had already been received by the bishop of Aversa, Ferrante’s chaplain, Pietro Brusca, and discussions had also begun to determine the size of the bride’s dowry and the provisions for her new household in Ferrara, although these arrangements would only be finalised when Ercole’s brother, Sigismondo, arrived in Naples for the proxy marriage on 16 May 1473. In this chapter I will use a collection of diplomatic documents in the Estense archive in Modena to follow the progress of the marriage negotiations in Naples, from the arrival of Facino in August 1472 with a mandate from Ercole to arrange a marriage with Eleonora, until the moment when Sigismondo d’Este slipped his brother’s ring onto the bride’s finger. Among these documents are Facino’s reports of his tortuous dealings with Ferrante’s team of negotiators and the acrimonious letters in which Diomede Carafa, acting on Ferrante’s behalf, demanded certain minimum standards for Eleonora’s household in Ferrara. It is an added bonus that these letters, together with a small collection of what may only loosely be referred to as love letters from Ercole to his bride, give occasional glimpses of Eleonora as a real person, by no means a 1 A marriage per verba de presenti implied that the couple were actually man and wife from that time on. -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. -

A COMPARATIVE APPROACH to the CITY-STATE Michael Paul Martoccio Ideal Types and Negotiated Identities: a Comparative Approach to the City-State

Journal of Interdisciplinary History, xlv:2 (Autumn, 2014), 187–200. A COMPARATIVE APPROACH TO THE CITY-STATE Michael Paul Martoccio Ideal Types and Negotiated Identities: A Comparative Approach to the City-State The City-State in Europe, 1000–1600: Hinterland, Territory, Region. By Tom Scott (New York, Oxford University Press, 2012) 382 pp. $65.00 The Italian Renaissance State. Edited by Andrea Gamberini and Isabella Lazzarini (New York, Cambridge University Press, 2012) 634 pp. $166.00 City-states hold a special place in the political history of medieval and early modern Europe. The urban belt—the populated core of premodern Europe, which included the central and northern Ital- ian communes; the Alpine cantons; the southern and eastern Franconian, Swabian, and Rhenish cities; and the urban centers of the Low Countries along the Rhine—followed a backward route to the modern state. Flush with capital, the urban belt failed to pro- duce consolidated states, instead forming a series of incomplete, federal, or half-made modern states. Yet cities were more than just “islands of capital” in a sea of territorial lords; they also were politi- cal innovators, achieving robust representative institutions and such ªscal advances as public credit. Central to the study of the European city-states is how to address these polities comparatively—how to explain the rise and decline of certain city-states and the survival and persistence of others and to relate a wide-range of public institutions within many different urban areas. Notwithstanding their historical im- portance, however, the comparative study of premodern European city-states has often been more a subject for political scientists and sociologists than for historians.