John in MEMORY of Sendy PAUSTOVSKY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

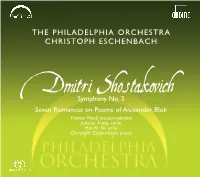

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

Ogonek Digital Archive

Ogonek Digital Archive The most important publication on Soviet culture and everyday life Ogonek was one of the oldest weekly magazines in Russia, having been in continuous publication since 1923. Ogonek had rather inauspicious beginnings. Unlike Pravda or Izvestiia, born, as they were, in the cauldrons of the Russian Revolution, Ogonek, soon after its birth in 1923, came to serve one grand purpose only – to fulfill the task of cultural validation and legitimation of the Soviet system. Ogonek would serve its mission with certain aplomb and sophistication. Lacking the crudeness and the bombast of the main organs of Communist Party propaganda, Ogonek was able to become one of the most influential shapers and reflectors of the public character of the Soviet culture. Every self-respecting Soviet intellectual was expected to read Ogonek if they were to stay informed about the cultural world in which they lived and moved. The importance of Ogonek as a primary source for research into the Soviet Union and bolshevization of its cultural and social landscapes cannot be overestimated. Because of its mass circulation and popularity, it was able to unite Soviet Union’s geographically and culturally diverse population through culturally important and imposing narratives. If in the West, and especially in the United States, cultural trends were the result of complex negotiations between market research, supply, and demand, in the Soviet Union cultural trends were more or less state approved top-down affairs. Ogonek was an important vehicle for the conveyance of the Soviet cultural idiom to the reading public. Key Stats Access over 90 years of Soviet and Russian Archive: 1923-2020 culture Language: Russian The Ogonek digital archive contains all obtainable published issues from 1923 on. -

A Data Analysis Tool for the Corpus of Russian Poetry

Olga Lyashevskaya, Kristina Litvintseva, Ekaterina Vlasova, Eugenia Sechina A DATA ANALYSIS TOOL FOR THE CORPUS OF RUSSIAN POETRY BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: LINGUISTICS WP BRP 77/LNG/2018 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE. SERIES: LINGUISTICS Olga Lyashevskaya1, Kristina Litvintseva2, Ekaterina Vlasova3, Eugenia Sechina4 A Data Analysis Tool for the Corpus of Russian Poetry5 A data analysis tool of the Corpus of Russian Poetry (a part of the Russian National Corpus) is designed for quantitative research in various areas of versology and linguistics aspects of the poetic texts. The core part, a frequency database of the corpus, includes annotation at the level of texts, verses, words as well as patterns of words, letters, and stress. The tool allows a user to study certain properties (e. g. rhyming patterns, lexical co-occurrence) taken alone and in their interaction, both in the whole corpus and in subcorpora. Besides that, it facilitates the contrastive studies of two chosen subcorpora. The paper reports a few case studies demonstrating applicable descriptive and exploratory methods and potential for further research in the field of the digital literary studies. JEL Classification: Z. Keywords: poetic corpora, quantitative linguistics, lexical markers, lexical diversity, rhyme, linguistic poetics, versology, Russian language, Russian National Corpus 1. Introduction Russian versology has always heavily relied on statistics data as the basis for predictions and generalizations on meter, rhyme, and other formal and linguistic features of poetic language (see Gasparov 2005, Taranovsky 2010, Jakobson et al. -

Friday, November 20, 2015 Registration Desk Hours: 7:00 A.M

This version of the program was last updated on June 8, 2015 For the most up-to-date program, see http://convention2.allacademic.com/one/aseees/aseees15/ Friday, November 20, 2015 Registration Desk Hours: 7:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. Registration Desk 1 and Grand Ballroom Prefunction Area - 5th Floor Cyber Café Hours: 7:00 a.m. - 6:45 p.m. – Franklin Hall Prefunction Area Exhibit Hall Hours: 9:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. Franklin Hall B Session 4 – Friday – 8:00-9:45 am Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession - Conference Suite 3 Bulgarian Studies Association - Meeting Room 309 Committee on Libraries and Information Resources Subcommittee on Collection Development - Conference Suite 2 International Association for the Humanities - Meeting Room 303 Soyuz-The Research Network for Post-Socialist Studies - Meeting Room 310 4-01 Vlast', Power, and Revolution: the Fundamental Political Conflicts of 1917 - Franklin Hall A Room 1 Chair: Rex A. Wade, George Mason U Papers: Semion Lyandres, U of Notre Dame "Opposition Politics on the Eve the February Uprising: Prerevolutionary Conspiracies and the Question of the First Provisional Government's Leadership" Lars Thomas Lih, Independent Scholar "Soglashatelstvo ('Agreementism'): The Fundamental Political Conflict of 1917" Ian Thatcher, U of Ulster (UK) "The First Provisional Government, March-May 1917" Disc.: Michael C. Hickey, Bloomsburg U 4-02 New Developments in Central and East European Politics - (Roundtable) - Franklin Hall A Room 2 Chair: Jane Leftwich Curry, Santa Clara U Federigo Argentieri, John Cabot U, Temple U - Rome (Italy) Taras Kuzio, U of Alberta (Canada) Paula M. -

Russian Poets and the October Revolution: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin and Others

Sylaiev, O., Razumenko, I., Tararak, O., Vorozhbit-Horbatiuk, V., Prokopchuk, I. / Volume 9 - Issue 27: 436-444 / March, 2020 436 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.34069/AI/2020.27.03.48 Russian Poets and the October Revolution: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin and Others Русские поэты и Октябрьская революция: Александр Блок, Сергей Есенин, Михаил Кузьмин и другие Poetas rusos y la revolución de octubre: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin y otros Received: January 22, 2020 Accepted: March 21, 2020 Written by: Oleksandr Sylaiev151 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-2388-5951 Iryna Razumenko152 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-3221-4340 Oleksandr Tararak153 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-9740-0750 Viktoriia Vorozhbit-Horbatiuk154 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5138-9226 Inna Prokopchuk155 ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9353-2169 Abstract Аннотация The article considers the question of the В статье рассматривается вопрос об идейно- ideological and creative evolution of famous творческой эволюции известных русских Russian poets at a turning point in the history of поэтов на переломном этапе истории ХХ the twentieth century - during the years of the столетия – в годы активного формирования active formation of a totalitarian state system тоталитарного государственного устройства и and its aesthetic socialist-realist doctrine. его эстетической соцреалистической Revolutionary maximalism, the idea of a доктрины. Революционный максимализм, идея complete renewal of all being, came not only полного обновления всего бытия шла не только from Marxism and the Bolsheviks, but was also от марксизма и большевиков, но prepared by literature, long before the подготавливалась и литературой, задолго до revolution, it had already “artistically matured” революции уже «вызрела» художественно в in the poetry of Alexander Blok, Sergey поэзии Александра Блока, Сергея Есенина, Yesenin, Osip Mandelstam, Vladimir Осипа Мандельштама, Владимира Mayakovsky and many others. -

Babel' in Context a Study in Cultural Identity B O R D E R L I N E S : R U S S I a N А N D E a S T E U R O P E a N J E W I S H S T U D I E S

Babel' in Context A Study in Cultural Identity B o r d e r l i n e s : r u s s i a n а n d e a s t e u r o p e a n J e w i s h s t u d i e s Series Editor: Harriet Murav—University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Editorial board: Mikhail KrutiKov—University of Michigan alice NakhiMovsKy—Colgate University David Shneer—University of Colorado, Boulder anna ShterNsHis—University of Toronto Babel' in Context A Study in Cultural Identity Ef r a i m Sic hEr BOSTON / 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2012 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved Effective July 29, 2016, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. ISBN 978-1-936235-95-7 Cloth ISBN 978-1-61811-145-6 Electronic Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2012 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com C o n t e n t s Note on References and Translations 8 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction 11 1 / Isaak Babelʹ: A Brief Life 29 2 / Reference and Interference 85 3 / Babelʹ, Bialik, and Others 108 4 / Midrash and History: A Key to the Babelesque Imagination 129 5 / A Russian Maupassant 151 6 / Babelʹ’s Civil War 170 7 / A Voyeur on a Collective Farm 208 Bibliography of Works by Babelʹ and Recommended Reading 228 Notes 252 Index 289 Illustrations Babelʹ with his father, Nikolaev 1904 32 Babelʹ with his schoolmates 33 Benia Krik (still from the film, Benia Krik, 1926) 37 S. -

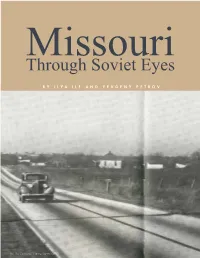

Missouri Through Soviet Eyes | the Confluence

ThroughMissouri Soviet Eyes BY ILYA ILF AND YEVGENY PETROV 48 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2012 Good travel writing can be powerful. Few things offer new insights quite like having familiar surroundings seen through fresh eyes. When that new perspective comes from a very different cultural context, the results can be even more startling. Such is the case with Soviet satirists Evgeny Ilf (1897-1937) and Yevgeny Petrov (1903- 1942), who were immensely popular writers in the Soviet Union in the late 1920s and 1930s. While working as special correspondents for Pravda (the Communist Party newspaper in the USSR) in 1935, the two came to the United States to embark on a two-month road trip across the country and back. They bought a Ford in New York in late October, teamed up with Solomon Trone (a retired engineer who had worked in the USSR for General Electric) Ilf and Petrov made this journey along national highways and his wife, Florence, whom they met there, and drove and state routes, which traveled through small towns to California and back. In April, Ogonek magazine and the countryside. They made a habit of picking up published the first of a series of photo essays based on the hitchhikers frequently, since it gave them a way to interview pictures Ilf took along the way. A year later, in 1937, an “real” Americans. They arrived in Hannibal after spending account of their journey and a selection of the photos were time in Chicago, where they complained about the bitter published in both the Soviet Union and the United States cold. -

Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial Board T

GUIDE Odessa 2017 UDC 069:801 (477.74) О417 Editorial board T. Liptuga, G. Zakipnaya, G. Semykina, A. Yavorskaya Authors A. Yavorskaya, G. Semykina, Y. Karakina, G. Zakipnaya, L. Melnichenko, A. Bozhko, L. Liputa, M. Kotelnikova, I. Savrasova English translation O. Voronina Photo Georgiy Isayev, Leonid Sidorsky, Andrei Rafael О417 Одеський літературний музей : Путівник / О. Яворська та ін. Ред. кол. : Т. Ліптуга та ін., – Фото Г. Ісаєва та ін. – Одеса, 2017. – 160 с.: іл. ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 Odessa Literary Museum: Guide / A.Yavorskaya and others. Editorial: T. Liptuga and others, - Photo by G.Isayev and others. – Odessa, 2017. — 160 p.: Illustrated Guide to the Odessa Literary Museum is a journey of more than two centuries, from the first years of the city’s existence to our days. You will be guided by the writers who were born or lived in Odessa for a while. They created a literary legend about an amazing and unique city that came to life in the exposition of the Odessa Literary Museum UDC 069:801 (477.74) Англійською мовою ISBN 978-617-7613-04-5 © OLM, 2017 INTRODUCTION The creators of the museum considered it their goal The open-air exposition "The Garden of Sculptures" to fill the cultural lacuna artificially created by the ideo- with the adjoining "Odessa Courtyard" was a successful logical policy of the Soviet era. Despite the thirty years continuation of the main exposition of the Odessa Literary since the opening day, the exposition as a whole is quite Museum. The idea and its further implementation belongs he foundation of the Odessa Literary Museum was museum of books and local book printing and the history modern. -

Construction and Tradition: the Making of 'First Wave' Russian

Construction and Tradition: The Making of ‘First Wave’ Russian Émigré Identity A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of History from The College of William and Mary by Mary Catherine French Accepted for ____Highest Honors_______________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Frederick C. Corney, Director ________________________________________ Tuska E. Benes ________________________________________ Alexander Prokhorov Williamsburg, VA May 3, 2007 ii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Part One: Looking Outward 13 Part Two: Looking Inward 46 Conclusion 66 Bibliography 69 iii Preface There are many people to acknowledge for their support over the course of this process. First, I would like to thank all members of my examining committee. First, my endless gratitude to Fred Corney for his encouragement, sharp editing, and perceptive questions. Sasha Prokhorov and Tuska Benes were generous enough to serve as additional readers and to share their time and comments. I also thank Laurie Koloski for her suggestions on Romantic Messianism, and her lessons over the years on writing and thinking historically. Tony Anemone provided helpful editorial comments in the very early stages of the project. Finally, I come to those people who sustained me through the emotionally and intellectually draining aspects of this project. My parents have been unstinting in their encouragement and love. I cannot express here how much I owe Erin Alpert— I could not ask for a better sounding board, or a better friend. And to Dan Burke, for his love and his support of my love for history. 1 Introduction: Setting the Stage for Exile The history of communities in exile and their efforts to maintain national identity without belonging to a recognized nation-state is a recurring theme not only in general histories of Europe, but also a significant trend in Russian history. -

Slavic Lang M98T GE Form

General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Slavic Languages/Jewish Studies M98T Crisis and War: the Jewish Experience in the Soviet Course Title ‘Promised Land’ 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis X • Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. The course fulfills both the Social Analysis and the Literary and Cultural Analysis prerequisites. The course provides the basic means to explore and appreciate cultural diversity through literature, film, art, and song. The course, likewise, focuses on a particular historical and social experience. That experience forces us to ask questions pertinent not only to the field of history and social sciences, but also to further investigate our current role(s) in the multifaceted and multicultural world. 3. List faculty member(s) and teaching fellow who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Naya Lekht, teaching fellow and David MacFadyen, faculty mentor 4. Indicate what quarter you plan to teach this course: 2011-2011 Winter____X______ Spring__________ 5. GE Course units _____5______ 6. Please present concise arguments for the GE principles applicable to this course. General Knowledge The course introduces students not only to historical facts, but more importantly, to current working models of minority cultures as well as several leading methodologies in history, literature, and anthropology. -

Newsletter of the Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies

ISSN 1536-4003 University of California, Berkeley Newsletter of the Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies Spring 2005 Volume 22, Number 1 Notes from the Director In this issue: Welcome to the spring semester! I hope you all had a good holiday. We at the Institute are looking forward to a very rich program of lectures and Notes from the Director ................... 1 conferences. I will outline only some of them here. On Thursday, Febru- Campus Visitors .............................. 2 ary 3, we will hold the XXth Annual Colin Miller Memorial Lecture. This Spring Courses ............................... 3 year, our speaker is Istvan Deak, Seth Low Professor Emeritus at Colum- In Memoriam ................................... 4 bia University, a prominent historian of Central and Eastern Europe, and a Jarrod Tanny regular contributor to the New York Review of Books. Professor Deak’s Yids from the Hood: The Image of the topic is “The Post-World War II Political Purges in Europe.” We hope to Jewish Gangster from Odessa .......... 5 see many of you at the lecture in the Alumni House at 4 p.m. Kathryn D. Schild A Dialogue with Dostoevsky: Some of the giants in the field of Slavic and East European studies Orhan Pamuk's The Black Book ........ 9 are our own Berkeley colleagues. It gives me very special pleasure to Berkeley-Stanford Conference....... 11 announce a roundtable, “The Early Years of Slavic Studies at UC Berke- Bear Trek to St. Petersburg .......... 20 ley,” to be held on Thursday, February 17, at 2 p.m. in the Heyns Room of Degrees Awarded ......................... 21 the Faculty Club.