A Data Analysis Tool for the Corpus of Russian Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

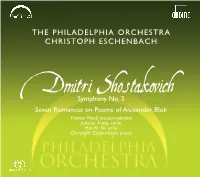

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

Russian Poets and the October Revolution: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin and Others

Sylaiev, O., Razumenko, I., Tararak, O., Vorozhbit-Horbatiuk, V., Prokopchuk, I. / Volume 9 - Issue 27: 436-444 / March, 2020 436 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.34069/AI/2020.27.03.48 Russian Poets and the October Revolution: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin and Others Русские поэты и Октябрьская революция: Александр Блок, Сергей Есенин, Михаил Кузьмин и другие Poetas rusos y la revolución de octubre: Alexander Blok, Sergey Yesenin, Mikhail Kuzmin y otros Received: January 22, 2020 Accepted: March 21, 2020 Written by: Oleksandr Sylaiev151 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-2388-5951 Iryna Razumenko152 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-3221-4340 Oleksandr Tararak153 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-9740-0750 Viktoriia Vorozhbit-Horbatiuk154 ORCID ID: 0000-0002-5138-9226 Inna Prokopchuk155 ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9353-2169 Abstract Аннотация The article considers the question of the В статье рассматривается вопрос об идейно- ideological and creative evolution of famous творческой эволюции известных русских Russian poets at a turning point in the history of поэтов на переломном этапе истории ХХ the twentieth century - during the years of the столетия – в годы активного формирования active formation of a totalitarian state system тоталитарного государственного устройства и and its aesthetic socialist-realist doctrine. его эстетической соцреалистической Revolutionary maximalism, the idea of a доктрины. Революционный максимализм, идея complete renewal of all being, came not only полного обновления всего бытия шла не только from Marxism and the Bolsheviks, but was also от марксизма и большевиков, но prepared by literature, long before the подготавливалась и литературой, задолго до revolution, it had already “artistically matured” революции уже «вызрела» художественно в in the poetry of Alexander Blok, Sergey поэзии Александра Блока, Сергея Есенина, Yesenin, Osip Mandelstam, Vladimir Осипа Мандельштама, Владимира Mayakovsky and many others. -

Construction and Tradition: the Making of 'First Wave' Russian

Construction and Tradition: The Making of ‘First Wave’ Russian Émigré Identity A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of History from The College of William and Mary by Mary Catherine French Accepted for ____Highest Honors_______________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Frederick C. Corney, Director ________________________________________ Tuska E. Benes ________________________________________ Alexander Prokhorov Williamsburg, VA May 3, 2007 ii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Part One: Looking Outward 13 Part Two: Looking Inward 46 Conclusion 66 Bibliography 69 iii Preface There are many people to acknowledge for their support over the course of this process. First, I would like to thank all members of my examining committee. First, my endless gratitude to Fred Corney for his encouragement, sharp editing, and perceptive questions. Sasha Prokhorov and Tuska Benes were generous enough to serve as additional readers and to share their time and comments. I also thank Laurie Koloski for her suggestions on Romantic Messianism, and her lessons over the years on writing and thinking historically. Tony Anemone provided helpful editorial comments in the very early stages of the project. Finally, I come to those people who sustained me through the emotionally and intellectually draining aspects of this project. My parents have been unstinting in their encouragement and love. I cannot express here how much I owe Erin Alpert— I could not ask for a better sounding board, or a better friend. And to Dan Burke, for his love and his support of my love for history. 1 Introduction: Setting the Stage for Exile The history of communities in exile and their efforts to maintain national identity without belonging to a recognized nation-state is a recurring theme not only in general histories of Europe, but also a significant trend in Russian history. -

Appendix! Fyodor Dostoevsky and Vladimir Solovyov*

Appendix! Fyodor Dostoevsky and Vladimir Solovyov* (In memory of Dr Nicolas M. Zernov, 1898-1980) The volume and scope of critical and commentarial literature devoted to Dostoevsky's thought in the century since his death is clear evidence of the richness and complexity encountered in his works. In the figure of Vladimir Solovyov - both in his person and his writings - we also encounter a high degree of complexity. Tracing the patterns of his thought, we find certain tensions and a number of striking incongruities. Here was - a man who was, at heart, a monarchist, but aroused the anger and suspicions of the Tsar and Holy Synod through his advocacy of theocratic government; a man who embraced so much that was characteristic of the Slavophiles, and yet was a staunch supporter of their arch-enemy, Peter the Great; a man so seemingly keen to reaffirm the worth of contemplative spirituality, but who personally resisted the decision to join a monastery, a step that he at one time regarded as 'flight' from the world. Those who knew Solovyov at first hand stressed what they regarded either as his sanctity or his eccentricity (his chudachestvo ). Accounts of the excitement generated by his university lectures on philosophy certainly show that he commanded a surprising degree of authority and respect. On the other hand, Solovyov had to contend with numerous uncharitable gibes and with accusations to the effect that he had set himself up as a 'prophet'. Perhaps his best response to adverse criticism of this kind was to deflate his *A Paper delivered at the VI Symposium of the International Dostoevsky Society, 9-16 August 1986, University of Nottingham. -

Poetry and Psychiatry

POETRY AND PSYCHIATRY Essays on Early Twentieth-Century Russian Symbolist Culture S t u d i e S i n S l av i c a n d R u ss i a n l i t e R at u R e S , c u lt u R e S , a n d H i S to Ry Series Editor: Lazar FLeishman (Stanford University) POETRY a n d PSYCHIATRY Essays on Early Twentieth-Century Russian Symbolist Culture Magnus L junggren Translated by Charles rougle Boston / 2014 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A bibliographic record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2014 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-61811-350-4 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61811-361-0 (electronic) ISBN 978-1-61811-369-6 (paper) Book design by Ivan Grave On the cover: Sergey Solovyov and Andrey Bely, 1904. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2014 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. -

Vyacheslav Ivanov and C.M. Bowra: a Correspondence from Two Corners on Humanism

BIRMINGHAM SLAVONIC MONOGRAPHS No. 36 Pamela Davidson VYACHESLAV IVANOV AND C.M. BOWRA: A CORRESPONDENCE FROM TWO CORNERS ON HUMANISM 1 In memoriam Dimitrii Vyacheslavovich Ivanov (1912-2003) Sergei Sergeevich Averintsev (1937-2004) 2 Дорогой друг мой, мы пребываем в одной культурной среде, как обитаем в одной комнате, где есть у каждого свой угол, но широкое окно одно, и одна дверь. [My dear friend, we inhabit one cultural world, just as we live in one room, where there is a corner for each person but one wide window and one door.] V.I. Ivanov to M.O. Gershenzon, June 1920 (from A Correspondence from Two Corners) He was a great man, of a kind very uncommon at any time and especially now. He really represented a great tradition and kept it alive by his great candour and sincerity and passion. I am very proud to have known him. C.M. Bowra to D.V. Ivanov, August 1949 3 CONTENTS Illustrations Acknowledgements Transcription and Transliteration Abbreviations Introduction Chapter One Ivanov and the ‘Good Humanistic Tradition’ Chapter Two Bowra as a Classical Scholar and Literary Critic Chapter Three Bowra’s Translations of Ivanov Chapter Four The Relationship and Meetings of Ivanov and Bowra Chapter Five The Letters of Ivanov and Bowra (1946-48) Conclusion Select Bibliography Index of Names and Works 4 Illustrations Photograph of V.I. Ivanov in Rome (courtesy of Rome Archive of Ivanov). Photograph of C.M. Bowra in Oxford (courtesy of the Oxford Mail). Facsimile of letter from C.M. Bowra to V.I. Ivanov of 3 November 1946 (Rome Archive of Ivanov). -

Mandelstam, Blok, and the Boundaries of Mythopoetic Symbolism Myopoetic Symbolism Mandelstam, Blok, and the Boundaries of Mythopoetic Symbolism

MANDELSTAM, BLOK, AND THE BOUNDARIES OF MYTHOPOETIC SYMBOLISM MYOPOETIC SYMBOLISM MANDELSTAM, BLOK, AND THE BOUNDARIES OF MYTHOPOETIC SYMBOLISM STUART GOLDBERG THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS | COLUMBUS Copyright © 2011 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Goldberg, Stuart, 1971– Mandelstam, Blok, and the boundaries of mythopoetic symbolism / Stuart Goldberg. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1159-5 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9260-0 (cd) 1. Russian poetry—20th century—History and criticism. 2. Symbolism in literature. 3. Mandel’shtam, Osip, 1891–1938—Criticism and interpretation. 4. Blok, Aleksandr Alek- sandrovich, 1880–1921—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PG3065.S8G65 2011 891.71'3—dc22 2011013260 Cover design by James A. Baumann Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Диночке с любовью CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii PART I Chapter 1 Introduction 3 Immediacy and Distance 3 “The living and dangerous Blok . .” 6 Symbolism and Acmeism: An Overview 8 The Curtain and the Onionskin 15 Chapter 2 Prescient Evasions of Bloom 21 PART II Chapter 3 Departure 35 Chapter 4 The Pendulum at the Heart of Stone 49 Chapter 5 Struggling with the Faith -

Solovyov Studies

IVANOVO STATE POWER UNIVERSITY SOLOVYOV STUDIES Issue 3(67) 2020 Solovyov Studies. Issue 3(67) 2020 Founder: Federal State-Financed Educational Institution of Higher Education «Ivanovo State Power Engineering University named after V.I. Lenin» The Journal has been published since 2001 ISSN 2076-9210 Editorial Board: М.V. Maksimov (Chief Editor), Doctor of Philosophy, Ivanovo, Russia I.I. Evlampiev (Deputy Chief editor), Doctor of Philosophy, St. Petersburg, Russia, I.A. Edoshina (Deputy Chief editor), Doctor of Cultural Studies, Kostroma, Russia S.D. Titarenko (Deputy Chief editor), Doctor of Philology, St. Petersburg, Russia, L.М. Маksimova (responsible secretary), Candidate of Philosophy, Ivanovo, Russia, Е.М. Amelina, Doctor of Philosophy, Moscow, Russia, I.V. Borisova, Research Scientist, Moscow, Russia, K.U. Burmistrov, Candidate of Philosophy, Moscow, Russia, A.U. Gacheva, Doctor of Philology, Moscow, Russia, N.U. Gryakalova, Doctor of Philology, St. Petersburg, Russia, K.V. Zenkin, Doctor of Art History, Moscow, Russia, N.V. Kotrelev, Senior Research Scientist, Moscow, Russia, N.N. Letina, Doctor of Cultural Studies, Yaroslavl, Russia, M.V. Medovarov, Doctor of History, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, B.V. Mezhuev, Candidate of Philosophy, Moscow, Russia, V.I. Moiseev, Doctor of Philosophy, Moscow, Russia, S.B. Rotsinskiy, Doctor of Philosophy, Moscow, Russia, V.V. Serbinenko, Doctor of Philosophy, Moscow, Russia, Е.А. Takho-Godi, Doctor of Philology, St. Petersburg, Russia, O.L. Fetisenko, Doctor of Philology, St. Petersburg, Russia, D.L. Shukurov, Doctor of Philology, Ivanovo, Russia, M.U. Edelstein, Candidate of Philology, Moscow, Russia. International Editorial Board: G.E. Aliaiev, Doctor of Philosophy, Poltava, Ukraine, R. Goldt, Doctor of Philology, Mainz, Germany, N.I. -

Three Long Poems

The Word That Causes Death’s Defeat ANNA AKHMATOVA The Word That Causes Death’s Defeat Poems of Memory g Translated, with an introductory biography, critical essays, and commentary, by Nancy K. Anderson Yale University Press New Haven & London Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College. Copyright ∫ 2004 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by James J. Johnson and set in Nofret Roman type by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Akhmatova, Anna Andreevna, 1889–1966. [Poems. English. Selections] The word that causes death’s defeat : poems of memory / Anna Akhmatova ; translated, with an introductory biography, critical essays, and commentary, by Nancy K. Anderson.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-300-10377-8 (alk. paper) 1. Akhmatova, Anna Andreevna, 1889–1966—Translations into English. 2. Akhmatova, Anna Andreevna, 1889–1966. I. Anderson, Nancy K., 1956– II. Title. PG3476.A217 2004 891.71%42—dc22 2004006295 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 Contents ggg Preface vii A Note on Style xiii PART I. -

The Culture of the Silver Age

Russian Culture Center for Democratic Culture 2012 The Intelligentsia without Revolution: The Culture of the Silver Age Andrei Ariev Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture Part of the Asian History Commons, European History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Political History Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Repository Citation Ariev, A. (2012). The Intelligentsia without Revolution: The Culture of the Silver Age. In Dmitri N. Shalin, 1-27. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture/14 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Article in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Culture by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Intelligentsia without Revolution: The Culture of the Silver Age Andrei Ariev The most effective definition of "the intelligentsia" might read: “Russian intellectuals who are generally opposed to the government.” But even Russia’s traditionally powerful government has collapsed at times, leaving a vacuum of authority. This was precisely the historical situation at the beginning of the twentieth century. -

Russia's Silver Age in Today's Russia

Document generated on 09/28/2021 11:21 a.m. Surfaces RUSSIA’S SILVER AGE IN TODAY’S RUSSIA Konstantin Azadovski TROISIÈME CONGRÈS INTERNATIONAL SUR LE DISCOURS Article abstract HUMANISTE. LA RÉSISTANCE HUMANISTE AU DOGMATISME The culture of Russia’s Silver Age (1890-1917) has taken its place in the history AUJOURD’HUI ET À LA FIN DU MOYEN ÂGE of the arts of the country after having been forbidden under the Soviet regime. THIRD INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON HUMANISTIC With a relative "thaw" under Khrushchev, the works of Sergei Esenin, Ivan DISCOURSE. HUMANISTIC RESISTANCE TO DOGMATISM TODAY Bunin and some of Marina Tsvetaeva’s works became available. Today, after AND AT THE END OF THE MIDDLE AGES the fall of the Soviet regime, what used to be forbidden is now widely Volume 9, 2001 published often in cheap editions. What used to be elite culture has become mass culture. However, it unclear how the culture of the Silver Age can address the problems of today's extremely politicized Russia. A similar problematic URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065062ar faces the new wave of interest for other cultural trends, which have also DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1065062ar garnered the particular interest of Russian society: the culture and literature of Russian emigration and the literature of the Underground. See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal ISSN 1188-2492 (print) 1200-5320 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Azadovski, K. (2001). RUSSIA’S SILVER AGE IN TODAY’S RUSSIA. Surfaces, 9. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065062ar Copyright © Konstantin Azadovski, 2001 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Booklet LONDON Ok.Indd 1 14.03.2011 23:51:14 INSTITUTE of RUSSIAN LITERATURE (PUSHKINSKIJ DOM) RUSSIAN ACADEMY of SCIENCES Makarova Emb

1 45 6 2 3 1. View of Pushkin House from the Neva River. The building was constructed in 1832; Giovanni (Ivan Frantsevich) Lucchini, architect 2. Grand Duke Constantine Constantinovich, cousin of Tsar Nicholas II and a founder of Pushkin House, 1910 (photograph) 3. Main staircase, Pushkin House 4. Academician Dmitry Likhachev (1906–1999) 5. Academician Alexander Panchenko (1937–2002) 6. Alexander Pushkin, Self-Portrait, 1828 23 The Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkinskij Dom — Pushkin House), Russian Academy of Pushkin House’s audio holdings are especially valuable because they include extremely rare re- Sci ences, dates its founding to December 15 (28), 1905, the day a state commission made the cordings of the folklore of the ethnic groups and tribes who inhabited the lands of the former decision to create the “House of Pushkin,” a special museum that would collect everything Russian Empire. Some of this material is in the now-dead languages of the people of the Rus- 7 connected with Russia’s preeminent literary artists. Grand Duke Constantine Constantinovich, sian North and Eastern Siberia, where, for example, recordings of a real shamanic ritual were president of the Imperial Academy of Sciences and cousin of Tsar Nicholas II, headed the com- made. The Phonogram Archive strives to make this audio material available to the public. In mission. Since that day more than a hundred years ago, Pushkin House has become a unique particular, it has begun releasing CDs in two series entitled “Russian Folk Traditions and Non- complex known around the world as the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House), Rus- Russian Traditions”.