Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dissertation Entitled Yoshimoto Taka'aki's Karl Marx

A Dissertation Entitled Yoshimoto Taka’aki’s Karl Marx: Translation and Commentary By Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy in History ________________________ Adviser: Dr. Peter Linebaugh ________________________ Dr. Alfred Cave ________________________ Dr. Harry Cleaver ________________________ Dr. Michael Jakobson ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo August 2008 An Abstract of Yoshimoto Taka’aki’s Karl Marx: Translation and Commentary Manuel Yang Submitted as partial fulfillment for the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of Toledo August 2008 In 1966 the Japanese New Left thinker Yoshimoto Taka’aki published his seminal book on Karl Marx. The originality of this overview of Marx’s ideas and life lay in Yoshimoto’s stress on the young Marx’s theory of alienation as an outgrowth of a unique philosophy of nature, whose roots went back to the latter’s doctoral dissertation. It echoed Yoshimoto’s own reformulation of “alienation” (and Marx’s labor theory of value) as key concept in his theory of literary language (What is Beauty in Language), which he had just completed in 1965, and extended his argument -- ongoing from the mid-1950s -- with Japanese Marxism over questions of literature, politics, and culture. His extraction of the theme of “communal illusion” from the early Marx foregrounds his second major theoretical work of the decade, Communal Illusion, which he started to serialize in 1966 and completed in 1968, and outlines an important theoretical closure to the existential, political, and intellectual struggles he had waged since the end of the ii Pacific War. -

Jenny Marx Du Même Auteur

Jenny Marx Du même auteur Ouvrages divers de Jérôme Fehrenbach Un député picard de Varennes à Waterloo : Louvet de la Somme (1757‑1818), Encrage, 2006 Une famille de la petite bourgeoisie parisienne de Louis XIV à Louis XVIII : les Gaugé et leurs alliances à travers les archives (1680‑1820), L’Harmattan, 2007 Le Général Legrand, d’Austerlitz à la Bérézina, Éditions Soteca, 2012 Les Fehrenbach, 1270‑1970, auto-édition, Copy Média, 2015 La Princesse Palatine, l’égérie de la Fronde, Éditions du Cerf, 2016 Von Galen, un évêque contre Hitler, Éditions du Cerf, 2018 Ouvrages de Jérôme Fehrenbach en collaboration Un cœur allemand – Karl von Wendt (1911‑1942), un catholique d’une guerre à l’autre, avec Florence Fehrenbach, Éditions Privat, 2006 Nous voulions tuer Hitler, avec Philipp von Boeselager, Éditions Perrin, 2008 Les Boca, avec Olivier Boca, auto-édition, Copy Média, 2018 Ballons montés – Correspondance et tendresse conjugale pendant l’année terrible (septembre 1870‑mai1871), avec Pierre Allorant, Éditions du Cerf, 2019 Jérôme Fehrenbach Jenny Marx LA TENTATION BOURGEOISE ISBN : 978-2-3793-3486-3 Dépôt légal – 1re édition : mars, 2021 © Passés composés / Humensis, 2021 170 bis, boulevard du Montparnasse, 75680 Paris cedex 14 Le code de la propriété intellectuelle n’autorise que « les copies ou reproductions strictement réser- vées à l’usage privé du copiste et non destinées à une utilisation collective » (article L 122-5) ; il auto- rise également les courtes citations effectuées pour un but d’exemple ou d’illustration. En revanche, « toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayants cause, est illicite » (article L 122-4). -

Ernst-Bloch-On-Karl-Marx.Pdf

ON KARL MARX ERNST BLOCH AN AZIMUTH BOOK HERDER AND HERDER Azimuth defines direction by generating an arc between a fixed point and a variable, between the determined truths of the past and the unknown data of the future. 197 1 HERDER AND HERDER NEW YORK 232 Madison Avenue, New York 100 16 Original edition: Uber Karl Marx, © 1968 by Suhrkamp Verlag; from Das Prinzip Hoffnung, 3 vols. (passim), © 1959, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main. Translated by John Maxwell. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-87750 English translation © 1971 by Herder and Herder, Inc. Manufactured in the United States "._ CONTENTS Marx as a Student 9 Karl Marx and Humanity: The Material of Hope 16 Man and Citizen in Marx 46 Changing the WorId: Marx's Theses on Feuerbach 54 Marx and the Dialectics of Idealism 106 The University, Marxism, and Philosophy 118 The Marxist Concept of Science 141 Epicurus and Karl Marx 153 Upright Carriage, Concrete Utopia 159 MARX AS A STUDENT True growth is always open and youthful, and youth implies growth. Youth, like growth, is restless; growth, like youth, would lay the future open in the present. Apathy is their common enemy, and they are allies in the fight for that which has never been but is now coming into its own. Now is its day; and its day is as young and as vital as those who proclaim it and keep faith with it. If we look back to the very dawn of our daytime, we look back to the young Marx in his first years of intellectual ferment. -

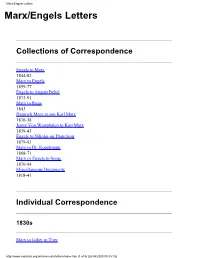

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters Collections of Correspondence Engels to Marx 1844-82 Marx to Engels 1859-77 Engels to August Bebel 1873-91 Marx to Ruge 1843 Heinrich Marx to son Karl Marx 1836-38 Jenny Von Westphalen to Karl Marx 1839-43 Engels to Nikolai-on Danielson 1879-93 Marx to Dr. Kugelmann 1868-71 Marx or Engels to Sorge 1870-94 Miscellaneous Documents 1818-41 Individual Correspondence 1830s Marx to father in Trier http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (1 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters November 10, 1837 1840s Marx to Carl Friedrich Bachman April 6, 1841 Marx to Oscar Ludwig Bernhard Wolf April 7, 1841 Marx to Dagobert Oppenheim August 25, 1841 Marx To Ludwig Feuerbach Oct 3, 1843 Marx To Julius Fröbel Nov 21, 1843 Marx and Arnold Ruge to the editor of the Démocratie Pacifique Dec 12, 1843 Marx to the editor of the Allegemeine Zeitung (Augsburg) Apr 14, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Bornstein Dec 30, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Heine Feb 02, 1845 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Sep 19, 1846 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Oct 23, 1846 Marx to Pavel Annenkov Dec 28, 1846 1850s Marx to J. Weydemeyer in New York (Abstract) March 5, 1852 1860s http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (2 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters Marx to Lasalle January 16, 1861 Marx to S. Meyer April 30, 1867 Marx to Schweitzer On Lassalleanism October 13, 1868 1870s Marx to Beesly On Lyons October 19, 1870 Marx to Leo Frankel and Louis Varlin On the Paris Commune May 13, 1871 Marx to Beesly On the Commune June 12, 1871 Marx to Bolte On struggles witht sects in The International November 23, 1871 Engels to Theodore Cuno On Bakunin and The International January 24, 1872 Marx to Bracke On the Critique to the Gotha Programme written by Marx and Engels May 5, 1875 Engels to P. -

Memória, Resistência E Intelectualidade Em Jenny Marx

Memória, Resistência e Intelectualidade em Jenny Marx THAIS DOMINGOS DOS SANTOS RODRIGUES* Resumo: Este artigo tem por objetivo elucidar a potência de resistência e intelectualidade de Jenny von Westphalen, colocando em debate o papel da mulher na produção de conhecimento e seus atrofiamentos numa sociedade patriarcal. Utilizamos como metodologia a análise de produções recentes e mais antigas como a biografia de Mary Gabriel – Amor e Capital: A Saga Familiar de Karl Marx e o Nascimento de Uma Revolução (2013), o filme O jovem Karl Marx (2017) de Raoul Peck e a biografia de Françoise Giroud: Jenny Marx ou a Mulher do Diabo (1996). A partir dessas obras procuramos elucidar uma Jenny que vai além da esposa, da mãe de sete filhos, da “bela prussiana”, mas com toda sua complexidade de uma grande revolucionária e peça fundamental para a elaboração da teoria marxiana, ou seja, com base nessas três linguagens oriundas de locais diferentes e em conjunto com a revisão bibliográfica analisamos as memórias de Jenny Marx enquanto mulher, comunista e intelectual. Encarando que a memória e o discurso estão sempre em disputa, trazemos o debate da historiografia feminina e a invisibilidade das mulheres na história apontando como meio de possibilidade de emergência de novas narrativas a utilização da história oral. Palavras-chave: Jenny Marx; Mulheres; História. Abstract: This article has as objective clarify the potency of resistance and intellectuality of Jenny von Westphalen, setting in debate the woman role in the production of knowledge and their atrophy in a patriarchal society. We resort as methodology the analysis of recent productions and oldest ones like the biography by Mary Gabiel - Love and Capital: Karl and Janny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution(2013), the movie The Young Karl Marx (2017) by Raoul Peck and the biography by Françoise Giroud: Jenny Marx or la femme du diable(1996). -

An All Too Human Communism

chapter 5 An All Too Human Communism 1 A Generalised Inversion When Marx left the editorship of the Rheinische Zeitung on 17 March 1843, the fate of the Cologne paper was inexorably sealed. Due to the radical nature of the liberalism that inspired the paper under Marx’s editorship, the Prussian government had for some time already effectively decided upon its suppres- sion. However, officially, it was only a ministerial order of 21 January 1843 that stated that the Rheinische Zeitung would cease publication by 31 March of the same year. This accordingly took place, despite Marx’s efforts to obtain a revoc- ation of the government decision and the petitions submitted by the citizens of Cologne and other Rhineland cities, as well an appeal on the part of the paper’s shareholders to the Prussian sovereign.1 The closure of the Rheinische Zeitung resulted in a determining change in both the public and private spheres of the young intellectual’s life. He was now 25 years old. Weighty issues, both practical and theoretical, loomed on the horizon for him. The previous year, after the death of his brother Hermann,2 difficulties arose with his mother, Henriette, who, wanting to see him take up a secure and advantageous profession, had already refused both any finan- cial assistance and access to his paternal inheritance. On the other hand, his engagement to Jenny von Westphalen had existed since the autumn of 1836 1 During the discussion on this of the General Meeting of the Shareholders of the Rheinische Zeitung, Jung, one of the directors, declared that ‘the newspaper has prospered in its present form, it has gained a surprising number of readers with astonishing rapidity’ (mecw 1, p. -

Marx, Engels, and the Abolition of the Family - Richard Weikart*

History of European Ideas, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 657-672, 1994 0191-6599 (93) E0194-6 _ . Copyright c 1994 Elseyier Science Ltd Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved 0191-6599/94 $7.00+ 0.00 MARX, ENGELS, AND THE ABOLITION OF THE FAMILY - RICHARD WEIKART* 'It is a peculiar fact' stated Engels a few months after Marx died, 'that with every great revolutionary movement the question of 'free love' comes to the foreground'.' By the mid- to late-nineteenth century it was clear to advocates and opponents alike that many socialists shared a propensity to reject the institution of the family in favour of 'free love', if not in practice, at least as an ideal. The Prussian and German Reich governments tried to muzzle the socialist threat to the family by drafting legislation in 1849,1874,1876 and 1894, outlawing, among other things, assaults on the family.2 However, the Anti-Socialist Law that Bismarck managed to pass in 1878 contained no mention of the family. The Utopian Socialists Charles Fourier and Robert Owen had preceded Marx and Engels in their rejection of traditional family relationships, and many nineteenth-century leftists followed their cue. The most famous political leader of the German socialists, August Bebel—though he was a staunch Marxist— wrote his immensely popular book, Die Frau und der Sozialismus, under the influence of Fourier's ideas. However, not all socialists in the nineteenth century were anti-family. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who wielded great influence in French socialist and anarchist circles, wanted to retain the family institution, which he loved and revered. -

Cronologia Della Vita E Dell'opera Di Karl Marx 1818-1883 (Pdf 556

CRONOLOGIA DELLA VITA E DELL’OPERA DI KARL MARX 1818-1883* 1818 5 maggio: Karl Marx nasce a Treviri, antica città medievale della Prussia renana e capoluogo del dipartimento francese della Sarre durante la domina- zione francese (1794-1814), centro di concerie e di fabbriche tessili situato in una regione vinicola caratterizzata dalla piccola proprietà contadina. L’indu- stria manufatturiera vi è poco sviluppata rispetto alle parti settentrionali della Renania, ove si trovano i centri metallurgici e cotonieri. Karl è il secondo- * La presente cronologia è basata su quella redatta da Maximilien Rubel per il vol. I delle Œuvres marxiane da lui curate per la “Bibliothèque de la Pléiade” di Gallimard. Laddove ci è parso opportuno, ne abbiamo integrato le informazioni. I titoli in corsivo, all’inizio di ogni anno, sono relativi ai principali scritti di Marx. I numeri tra parentesi quadre dopo ogni titolo rinviano a M. Rubel, Bibliographie des œuvres de Karl Marx, cit., e al relativo Supplément…, cit. La lettera P dopo il numero designa uno scritto postumo ed è seguìta dalla data di pubblicazione. Principali fonti utilizzate da Rubel: opere e corrispondenza di Marx ed Engels nelle loro diverse edizioni collettive; Fondo Marx-Engels dell’Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis (Amsterdam). Per i documenti assenti dalle edizioni collettive: Karl Marx. Chronik seines Lebens in Einzelndaten, a cura di Vladimir V. Adoratskij, cit.; B. Nicolaevsky – O. Maenchen-Helfen, Karl Marx. Eine Biographie, cit. Per ampliare la “Chronologie” di Rubel abbiamo usato: D. Riazanov (a cura di), Carlo Marx: uomo, pensatore, rivoluzionario, Fasani, Milano, 1946; Aa. Vv., Ricordi su Marx, cit.; K. -

Powerful Women Around Karl Marx—Examined Using the Figure of the Continuum

Sociology Study, Jan.-Feb. 2021, Vol. 11, No. 1, 17-32 doi: 10.17265/2159-5526/2021.01.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Powerful Women Around Karl Marx—Examined Using the Figure of the Continuum Christel Baltes-Löhr University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg Based on the treatise by Gerhard Bungert and Marlene Grund published in 1983, titled Karl Marx, Lenchen Demuth and the Saar, author Gisela Hoffmann, who lives in St. Wendel in the Saarland, Germany, which is the birthplace of Helena Demuth, wrote the play “Powerful Women Around Karl Marx”. It has been performed multiple times, the latest of which is on the occasion of International Women’s Day on March 8, 2018 in Trier, Germany. Along with presenting research on Helena Demuth as a historical person, this article will examine how Helena Demuth, as a historical and literary figure, can be said to embody a dynamic between exitus and new beginnings, changes and interferences. The article also examines how the figure of the Continuum, with the four dimensions physical (body), psychological (emotion), social (behavior), and sexual (desire), can be used to illuminate the person of Helena Demuth in all her facets, not the least of which are her connections to Jenny and Karl Marx. Keywords: gender relations, female figures, Helena Demuth, breaking points, Continuum Biographical Turning Point A look at the numerous publications on the occasion of Karl Marx’s 200th birthday on May 8, 2018 reveals a change of the discourses around Karl Marx, which can be understood as a biographical turning point and which, in connection with new insights into the historical context of Karl Marx’s life and work, changes the classification of its impact. -

Marx/Engels Biography Marx/Engels Biographical Archive

Marx/Engels Biography Marx/Engels Biographical Archive Karl Marx: Biographical overview (until 1869) by F. Engels (1869) Karl Marx by V.I. Lenin (1914) On the love between Jenny and Karl Marx by Eleanor Marx (his daughter; 1897-98) The Death of Karl Marx by F. Engels, various articles (1883) Fredrick Engels: Biographical Article by V. I. Lenin (1895) Encyclopedia Article Handwörterbuch der Staatswissenschaften (1892) Encyclopedia Article Brockhaus' Konversations-Lexikon (1893) Collections: Various media Interviews on both Engels and Marx (1871 - 1893) Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: An Intro A book by David Riazanov (1927) Recollections on Marx and Engels by Mikhail Bakunin (1871) Family of Marx and Engels: Jenny von Westphalen, (Jenny Marx) -- wife of Karl Marx Edgar von Westphalen Brother of Jenny Jenny Marx Daughter -- Various Articles by her Laura Marx Daughter Elenaor Marx Daughter http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/bio/index.htm (1 of 2) [26/08/2000 00:19:48] Marx/Engels Biography Charles Longuet Husband of Jenny Marx Paul Lafargue Husband of Laura Marx Edward Aveling Husband of Elanor Marx Helene Demuth Family friend and maid Works | Biography | Letters | Images | Contact Marx/Engels Internet Archive http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/bio/index.htm (2 of 2) [26/08/2000 00:19:48] Karl Marx Biography KARL MARX by Frederick Engels Short bio based on Engels' version written at the end of July 1868 for the German literary newspaper Die Gartenlaube -- whose editors decided against using it. Engels rewrote it around July 28, 1869 and it was published in Die Zukunft, No. 185, August 11, 1869 Translated by Joan and Trevor Walmsley Transcribed for the Internet by Zodiac [...] Karl Marx was born on May 5, 1818 in Trier, where he received a classical education. -

Know the Truth and the Truth Shall Set You Free

know the truth and the truth shall set you free How little we know of the scale of eternity. How dare we challenge the might and enormity of such wisdom and creation. A million worlds could exist in the heavens... beyond our site. Each with living beings, looking at the sky in wonder at the never ending universe. They may also think that no other intelligence exists... apart from themselves. But perhaps they do not share the arrogance of the human race. Perhaps they possess the intelligence to realize that all things are possible in the vastness of forever... Is it conceivable, that this earth of ours, which is but a speck of dust against the scale of reality, is not only being visited by other life forms but is being controlled by them. Let us not be blinded by our arrogance as to what is possible and what is not. Because we are children at the dawn of our creation with the universe as our classroom and intelligence beyond our imagination waiting to be tapped... when we are ready to receive it. Seek and the wonders you will see will reveal the true qualities of your universe. To the truth of your origins your hearts will go out. The beauty of your origins will surpass your belief and comprehension. And the infinite depth of your cosmic reality will remain part of your heritage in the mists of forever. The peace of understanding, is the beauty of creation. The word has been spoken and the spirit within you knows that home is eternity and existence is immortal.. -

Karl Marx: Man and Fighter

KARL MARX: MAN AND FIGHTER Boris Nicolaievsky and Otto Maenchen-Helfen ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: MARXISM KARL MARX: MAN AND FIGHTER Boris Nicolaievsky and Otto Maenchen-Helfen ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: MARXISM KARL MARX: MAN AND FIGHTER by BORIS NICOLAIEVSK Y and OTTO MAENCHEN-HELFEN Translated by Gwenda David and Eric Mosbacher METHUEN & CO. LTD. LONDON 36 Essex Street W. C .2 KARL MARX, I 8 I 8-1883 A Drawing from Life First published in any language in 1936 FOREWORD STRIFE has raged about Karl Marx fo r decades, and never has it been so embittered as at the present day. He has impressed his image on the time as no other man has done. To some he is a fiend, the arch-enemy of human civilisation, and the prince of chaos, while to others he is a far-seeing and beloved leader, guiding the human race towards a brighter fu ture. In Russia his teachings are the official doctrines of the state, while Fascist countries wish them exterminated. In the areas under the sway of the Chinese Soviets Marx's portrait · appears upon the bank-notes, while in Germany they have burned his books. Practically all the parties of the Socialist Workers' International, and the Communist parties in all countries, acknowledge Marxism, the eradication of which is the sole purpose of innumerable political leagues, associations and coalitions. The French Proudhonists of the sixties, the followers of Lassalle in Germany of the seventies, the Fabians in England before the War produced their own brand of Socialism which they opposed to that of Marx.