UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Theorizing Pō: Embodied Cosmogony and Polynesian National Narratives a Dissertation Submi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pablo Neruda - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Pablo Neruda - poems - Publication Date: 2011 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Pablo Neruda(12 July 1904 – 23 September 1973) Pablo Neruda was the pen name and, later, legal name of the Chilean poet and politician Neftalí Ricardo Reyes Basoalto. He chose his pen name after Czech poet Jan Neruda. Neruda wrote in a variety of styles such as erotically charged love poems as in his collection Twenty Poems of Love and a Song of Despair, surrealist poems, historical epics, and overtly political manifestos. In 1971 Neruda won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez once called him "the greatest poet of the 20th century in any language." Neruda always wrote in green ink as it was his personal color of hope. On July 15, 1945, at Pacaembu Stadium in São Paulo, Brazil, he read to 100,000 people in honor of Communist revolutionary leader Luís Carlos Prestes. During his lifetime, Neruda occupied many diplomatic positions and served a stint as a senator for the Chilean Communist Party. When Conservative Chilean President González Videla outlawed communism in Chile in 1948, a warrant was issued for Neruda's arrest. Friends hid him for months in a house basement in the Chilean port of Valparaíso. Later, Neruda escaped into exile through a mountain pass near Maihue Lake into Argentina. Years later, Neruda was a close collaborator to socialist President Salvador Allende. When Neruda returned to Chile after his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Allende invited him to read at the Estadio Nacional before 70,000 people. -

Arista Meeting: 2:00 - 2:50 MWF Office : Room : H 102 Office Hours: Phone

Instructor: Noelani Arista Meeting: 2:00 - 2:50 MWF Office : Room : H 102 Office Hours: Phone: Syllabus Religion 250 Hawaiian Religion AIMS OF THIS _COURSE l. TO COMMUNICATE THE COMPLEXITY AND DIVERSITY OF HAWAIIAN RELIGIOUS BELIEF AND PRACTICE. 2. TO ENCOURAGE STUDENTS TO CONTINUE TO READ, WRITE AND THINK CRITICALLY ABOUT HAWAIIAN CULTURE AND RELIGION. 3. TO PROVIDE AN INTRODUCTION TO THE WORLD VIEW, MYTH, AND RITUAL OF KA POT KAHWO'THE PEOPLE OF OLD HAWAII. 4. TO INSTILL A FEELING OF THE HARMONY AND RICHNESS OF HAWAIIAN RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS AND ITS ENHANCEMENT OF LIFE. 5. TO EXAMINE THE VALUES OF THE PEOPLE OF OLD HAWAII AND THE RELATIONSHIP OF THESE VALUES TO THE PRESENT DAY. Grades : Grading is based on a scale of 350 points, 2 papers worth 50 points each, 2 exams worth 100 points each and 1 oral presentation worth 50 points. 315 points and up A 280-314 B 245-279 C 210-244 D 209 points and under F Your Responsibilities (Course Requirements) 1 . H `ike : There will be two ho`ike (examinations) ; multiple choice, matching, short answer and essay format, based upon the assigned reading, lecture and classroom discussion. 2. Na pepa: (papers) : Each student will write two (4-6 page, typed, double spaced) papers. Topics will be chosen in consultation with the instructor. These papers should be both interesting and true and show research and reflection. My policy is that late papers will only be accepted if you notify me in person and in advance that your paper will not be on time. -

Lāhui Naʻauao: Contemporary Implications of Kanaka Maoli Agency and Educational Advocacy During the Kingdom Period

LĀHUI NAʻAUAO: CONTEMPORARY IMPLICATIONS OF KANAKA MAOLI AGENCY AND EDUCATIONAL ADVOCACY DURING THE KINGDOM PERIOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN EDUCATION MAY 2013 By Kalani Makekau-Whittaker Dissertation Committee: Margaret Maaka, Chairperson Julie Kaʻomea Kerry Laiana Wong Sam L. Noʻeau Warner Katrina-Ann Kapā Oliveira UMI Number: 3572441 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3572441 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS E ke kini akua, nā ʻaumākua, a me nā kiaʻi mai ka pō mai, ke aloha nui iā ʻoukou. Mahalo ʻia kā ʻoukou alakaʻi ʻana mai iaʻu ma kēia ala aʻu e hele nei. He ala ia i maʻa i ka hele ʻia e oʻu mau mākua. This academic and spiritual journey has been a humbling experience. I am fortunate to have become so intimately connected with the kūpuna and their work through my research. The inspiration they have provided me has grown exponentially throughout the journey. -

Pacific Islands Program

/ '", ... it PACIFIC ISLANDS PROGRAM ! University of Hawaii j Miscellaneous Work Papers 1974:1 . BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE MATERIALS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII, MANOA CAMPUS Second Printing, 1979 Photocopy, Summer 1986 ,i ~ Foreword Each year the Pacific Islands Program plans to duplicate inexpensively a few work papers whose contents appear to justify a wider distribution than that of classroom contact or intra-University circulation. For the most part, they will consist of student papers submitted in academic courses and which, in their respective ways, represent a contribution to existing knowledge of the Pacific. Their subjects will be as varied as is the multi-disciplinary interests of the Program and the wealth of cooperation received from the many Pacific-interested members of the University faculty and the cooperating com munity. Pacific Islands Program Room 5, George Hall Annex 8 University of Hawaii • PRELIMINARY / BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE MATERIALS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII, MANOA CAMPUS Compiled by Nancy Jane Morris Verna H. F. Young Kehau Kahapea Velda Yamanaka , . • Revised 1974 Second Printing, 1979 PREFACE The Hawaiian Collection of the University of Hawaii Library is perhaps the world's largest, numbering more than 50,000 volumes. As students of the Hawaiian language, we have a particular interest in the Hawaiian language texts in the Collection. Up to now, however, there has been no single master list or file through which to gain access to all the Hawaiian language materials. This is an attempt to provide such list. We culled the bibliographical information from the Hawaiian Collection Catalog and the Library she1flists. We attempted to gather together all available materials in the Hawaiian language, on all subjects, whether imprinted on paper or microfilm, on tape or phonodisc. -

Indigenous New Zealand Literature in European Translation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Journal Systems at the Victoria University of Wellington Library A History of Indigenous New Zealand Books in European Translation OLIVER HAAG Abstract This article is concerned with the European translations of Indigenous New Zealand literature. It presents a statistical evaluation of a bibliography of translated books and provides an overview of publishing this literature in Europe. The bibliography highlights some of the trends in publishing, including the distribution of languages and genres. This study offers an analysis of publishers involved in the dissemination of the translations and retraces the reasons for the proliferation of translated Indigenous books since the mid-1980s. It identifies Indigenous films, literary prizes and festivals as well as broader international events as central causes for the increase in translations. The popular appeal of Indigenous literature of Aotearoa/New Zealand has increased significantly over the last three decades. The translation of Indigenous books and their subsequent emergence in continental European markets are evidence of a perceptible change from a once predominantly local market to a now increasingly globally read and published body of literature. Despite the increase in the number of translations, however, little scholarship has been devoted to the history of translated Indigenous New Zealand literature.1 This study addresses that lack of scholarship by retracing the history of European translations of this body of literature and presenting extensive reference data to facilitate follow-up research. Its objective is to present a bibliography of translated books and book chapters and a statistical evaluation based on that bibliography. -

The Mythology of the Ara Pacis Augustae: Iconography and Symbolism of the Western Side

Acta Ant. Hung. 55, 2015, 17–43 DOI: 10.1556/068.2015.55.1–4.2 DAN-TUDOR IONESCU THE MYTHOLOGY OF THE ARA PACIS AUGUSTAE: ICONOGRAPHY AND SYMBOLISM OF THE WESTERN SIDE Summary: The guiding idea of my article is to see the mythical and political ideology conveyed by the western side of the Ara Pacis Augustae in a (hopefully) new light. The Augustan ideology of power is in the modest opinion of the author intimately intertwined with the myths and legends concerning the Pri- mordia Romae. Augustus strove very hard to be seen by his contemporaries as the Novus Romulus and as the providential leader (fatalis dux, an expression loved by Augustan poetry) under the protection of the traditional Roman gods and especially of Apollo, the Greek god who has been early on adopted (and adapted) by Roman mythology and religion. Key words: Apollo, Ara, Augustus, Pax Augusta, Roma Aeterna, Saeculum Augustum, Victoria The aim of my communication is to describe and interpret the human figures that ap- pear on the external western upper frieze (e.g., on the two sides of the staircase) of the Ara Pacis Augustae, especially from a mythological and ideological (i.e., defined in the terms of Augustan political ideology) point of view. I have deliberately chosen to omit from my presentation the procession or gathering of human figures on both the Northern and on the Southern upper frieze of the outer wall of the Ara Pacis, since their relationship with the iconography of the Western and of the Eastern outer-upper friezes of this famous monument is indirect, although essential, at least in my humble opinion. -

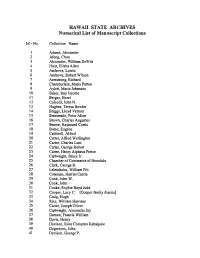

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections M-No. Collection Name 1 Adams, Alexander 2 Afong, Chun 3 Alexander, WilliamDe Witt 4 Hunt, Elisha Allen 5 Andrews, Lorrin 6 Andrews, Robert Wilson 7 Armstrong,Richard 8 Chamberlain, MariaPatton 9 Aylett, Marie Johannes 10 Baker, Ray Jerome 11 Berger, Henri 12 Colcord, John N. 13 Hughes, Teresa Bowler 14 Briggs, Lloyd Vernon 15 Brinsmade, Peter Allen 16 Brown, CharlesAugustus 17 Brown, Raymond Curtis 18 Burns, Eugene 19 Caldwell, Alfred 20 Carter, AlfredWellington 21 Carter,Charles Lunt 22 Carter, George Robert 23 Carter, Henry Alpheus Pierce 24 Cartwright, Bruce Jr. 25 Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu 26 Clark, George R. 27 Leleiohoku, William Pitt 28 Coleman, HarrietCastle 29 Cook, John W. 30 Cook, John 31 Cooke, Sophie Boyd Judd 32 Cooper, Lucy C. [Cooper family diaries] 33 Craig, Hugh 34 Rice, William Harrison 35 Carter,Joseph Oliver 36 Cartwright,Alexander Joy 37 Damon, Francis William 38 Davis, Henry 39 Davison, Rose Compton Kahaipule 40 Degreaves, John 41 Denison, George P. HAWAIi STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript collections M-No. Collection Name 42 Dimond, Henry 43 Dole, Sanford Ballard 44 Dutton, Joseph (Ira Barnes) 45 Emma, Queen 46 Ford, Seth Porter, M.D. 47 Frasher, Charles E. 48 Gibson, Walter Murray 49 Giffard, Walter Le Montais 50 Whitney, HenryM. 51 Goodale, William Whitmore 52 Green, Mary 53 Gulick, Charles Thomas 54 Hamblet, Nicholas 55 Harding, George 56 Hartwell,Alfred Stedman 57 Hasslocher, Eugen 58 Hatch, FrancisMarch 59 Hawaiian Chiefs 60 Coan, Titus 61 Heuck, Theodor Christopher 62 Hitchcock, Edward Griffin 63 Hoffinan, Theodore 64 Honolulu Fire Department 65 Holt, John Dominis 66 Holmes, Oliver 67 Houston, Pinao G. -

1 Revised Aug. 29, 2019

1 Revised Aug. 29, 2019 Upheaval & Reconstruction | October 17 – 20, 2019 | MSATORONTO2019.ORG 2 Table of Contents IntroDuction from the Local Hosting Committee ...................................................................................................... 3 Sponsors ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 MSA Toronto 2019 at a Glance ................................................................................................................................. 5 Plenary Sessions ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Social anD Cultural Events ......................................................................................................................................... 7 LanD AcknowleDgement ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Note on Accessibility ................................................................................................................................................. 9 ThursDay, October 17 ............................................................................................................................................. 10 FriDay, October 18 ................................................................................................................................................. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

The Semantics of Chaos in Tjutčev

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 171 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Sarah Pratt The Semantics of Chaos in Tjutčev Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH.Sarah Pratt - 9783954791286 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:00:10AM via free access S l a v is t ic h e B eiträg e BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON JOHANNES HOLTHUSEN ■ HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER • JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 171 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN Sarah Pratt - 9783954791286 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:00:10AM via free access 00050432 SARAH PRATT THE SEMANTICS OF CHAOS IN TJUTCEV VERLAG OTTO SAGNER • MÜNCHEN 1983 Sarah Pratt - 9783954791286 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:00:10AM via free access This work constitutes a portion of a larger work by the author entitled Alternatives in Russian Romanticism: The Poetry of Tiutchev and Baratynskii, © 1983 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior Uni- versity. It has been published by permission of Stanford University Press. All rights reserved. Bayerische ļ ו i-Miothek I'־ļ Staats ISBN 3-87690-261 -4 © Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1983 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, München Druck: Gräbner, Altendorf Sarah Pratt - 9783954791286 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:00:10AM via free access 00050432 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For inspiration and guidance in this endeavor I owe a debt of gratitude to Professor Richard Gustafson of Barnard College, who introduced me to Russian poetry and, most specially, to the poetry of Tjutčev. -

Sharks Upon the Land Seth Archer Index More Information Www

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17456-6 — Sharks upon the Land Seth Archer Index More Information Index ABCFM (American Board of ‘anā‘anā (sorcery), 109–10, 171, 172, 220 Commissioners for Foreign Missions), Andrews, Seth, 218 148, 152, 179, 187, 196, 210, 224 animal diseases, 28, 58–60 abortion, 220 annexation by US, 231, 233–34 adoption (hānai), 141, 181, 234 Aotearoa. See New Zealand adultery, 223 Arago, Jacques, 137 afterlife, 170, 200 Armstrong, Clarissa, 210 ahulau (epidemic), 101 Armstrong, Rev. Richard, 197, 207, 209, ‘aiea, 98–99 216, 220, 227 ‘Aikanaka, 187, 211 Auna, 153, 155 aikāne (male attendants), 49–50 ‘awa (kava), 28–29, 80, 81–82, 96, 97, ‘ai kapu (eating taboo), 31, 98–99, 124, 135, 139, 186 127, 129, 139–40, 141, 142, 143 bacterial diseases, 46–47 Albert, Prince, 232 Baldwin, Dwight, 216, 221, 228 alcohol consumption, 115–16, baptism, 131–33, 139, 147, 153, 162, 121, 122, 124, 135, 180, 186, 177–78, 183, 226 189, 228–29 Bayly, William, 44 Alexander I, Tsar of Russia, 95, 124 Beale, William, 195–96 ali‘i (chiefs) Beechey, Capt. Richard, 177 aikāne attendants, 49–50 Bell, Edward, 71, 72–73, 74 consumption, 122–24 Beresford, William, 56, 81 divine kingship, 27, 35 Bible, 167, 168 fatalism, 181, 182–83 Bingham, Hiram, 149, 150, 175, 177, 195 genealogy, 23, 26 Bingham, Sybil, 155, 195 kapu system, 64, 125–26 birth defects, 52 medicine and healing, 109 birth rate, 206, 217, 225, 233 mortality rates, 221 Bishop, Rev. Artemas, 198, 206, 208 relations with Britons, 40, 64 Bishop, Elizabeth Edwards, 159 sexual politics, 87 Blaisdell, Richard Kekuni, 109 Vancouver accounts, 70, 84 Blatchley, Abraham, 196 venereal disease, 49 Blonde (ship), 176 women’s role, 211 Boelen, Capt. -

Docuitnresune

DOCUitnRESUNE ED 1.18 513 SO 008 920 AUTHOR Jelinek, James John TITLE Principles and Values in School and SoCiety: The Fourth Yearbook of-the Arizona Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. ySTITUTION Arizona Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. PUB DATE 76 NOTE 192p.; For a related document, see SO*008 919 AVAILABLE FROM Dr. James John Jelinek, Editor of Yearbooks, Arizona Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, C011 ge of Education, Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona 85281 ($15300 paper) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 PlusPoste,HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS' *Curriculum Development; Educational Needs; Educational Philosophy; Elementary Secondary Education; Foundations of Education; Higher Education; Humanistic Education; *Moral Development; Moral VaIties; Problem Solving; *Social Sciences; *Values; Yearbooks e .ABST.11,,g2 This yearbook records some basic ideas on values education which the author previously presented to lay and professional audiences. The first part of the doiFument focuses on the formulation of problems\and principles. A principle is defined as ,a solution to a problem. Seventy principles are identified and listed. Zor example, one principle is an attitude--if conflict among forms of behavior rages within the individual, then attitudes emerge. The second part examines values-and the nature of human values, andlists 797 values in school and society. The last part of the document places the 70 principles and 797 values into the contexts of materials on the formation of problems and solutions, theidentifying and learning of human values, leatning, objectives, creativity, criteria for the evaluation of schools, criteria of philosophy and objectives of schools and the school and community for use in the accreditation of schools,'outcomes of training as contrasted 111-1.11 teaching, and processes of humanization/dehumanization in the schools.