Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Note

Research Note The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: A Work in Progress Robert Blust and Stephen Trussel UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA AND TRUSSEL SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT The Austronesian comparative dictionary (ACD) is an open-access online resource that currently (June 2013) includes 4,837 sets of reconstructions for nine hierarchically ordered protolanguages. Of these, 3,805 sets consist of single bases, and the remaining 1,032 sets contain 1,032 bases plus 1,781 derivatives, including affixed forms, reduplications, and compounds. His- torical inferences are based on material drawn from more than 700 attested languages, some of which are cited only sparingly, while others appear in over 1,500 entries. In addition to its main features, the ACD contains sup- plementary sections on widely distributed loanwords that could potentially lead to erroneous protoforms, submorphemic “roots,” and “noise” (in the information-theoretic sense of random lexical similarity that arises from historically independent processes). Although the matter is difficult to judge, the ACD, which prints out to somewhat over 3,000 single-spaced pages, now appears to be about half complete. 1. INTRODUCTION. 1 The December 2011 issue of this journal carried a Research Note that described the history and present status of POLLEX, the Polynesian Lexicon project initiated by the late Bruce Biggs in 1965, which over time has grown into one of the premier comparative dictionaries available for any language family or major subgroup (Greenhill and Clark 2011). A theme that runs through this piece is the remark- able growth over the 46 years of its life (at that time), not just in the content of the dictio- nary, but in the technological medium in which the material is embedded. -

Holle Lists: Vocabularies in Languages of Indonesia, Vol. I: Introductory Volume

PACIFIC L1NGUISTICS Se�ie� V - No. 17 HOLLE LISTS: VOCABULARIES IN LANGUAGES OF INDONESIA VOL. 1: INTRODUCTORY VOLUME (MATERIALS IN LANGUAGES OF INDONESIAJ No.1) W.A.L. Stokhof, ed., in cooperation with Lia Saleh-Bronkhorst Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Stokhof, W.A.L. editor. Holle lists: Vocabularies in languages of Indonesia, Vol. I: Introductory volume. D-17, vi + 154 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1980. DOI:10.15144/PL-D17.cover ©1980 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Ling ui�tic Ci�cle 06 Canbe��a and consists of four series: SERIES A - OCCASIONA L PAPERS SERIES B - MONOGRAPHS SERIES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS EDITOR: S.A. Wurm. ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton. EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B. Bender, University of Hawaii J. Lynch, University of Papua New D. Bradley, University of Melbourne Guinea A. Capell, University of Sydney K.A. McElhanon, University of Texas S. Elbert, University of Hawaii H. McKaughan, University of Hawaii K. Franklin, Summer Institute of P. MUhlh�usler, Linacre College, Oxford Linguistics G.N. O'Grady, University of Victoria, W.W. Glover, Summer Institute of B.C. Linguistics A.K. Pawley, University of Hawaii G. Grace, University of Hawaii K. Pike, University of Michigan; Summer M.A.K. Halliday, University of Institute of Linguistics Sydney E.C. Polome, University of Texas A. -

Deconstructing the Waves of Austronesian Migration to Madagascar and the East African Coast

Deconstructing the waves of Austronesian migration to Madagascar and the East African Coast 24th October, 2015 University of Wisconsin, Madison Roger Blench Chief Research Officer, Kay Williamson Educational Foundation McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge Adjunct Professor, University of New England, Armidale Academic Visitor, Rajiv Gandhi University, Arunachal Pradesh What’s the issue I? It has long been accepted (since the 17th century) that Malagasy is an Austronesian language Since Dahl (1960) it has been accepted that the nearest relatives within Austronesian are the Barito languages of SE Borneo However, as we know more about both Malagasy and Bornean languages, it has become increasingly clear the story isn’t as simple as that. Sander Adelaar pointed out some time ago that wind names and many terms to do with seafaring are direct borrowings from Malay Blench (and others) point to the borrowing of natural world terms (especially animal names) from coastal Bantu What’s the issue II? Robert Blust (Austronesian Comparative Dictionary) points out that some Malagasy roots are not attested in Borneo languages Beaujard (in his Tanala dictionary and subsequent papers) identifies a number of roots from Sulawesi languages which are not attested in general Austronesian but which are reconstructed by Mills (1975) All of this points to a specific Sulawesi component Less clear is a Philippines component; Malagasy has a few words which appear to be borrowed from Philippines languages It is also possible these are the result of Iberian trans- Indian Ocean traffic, post 16th century Models for the settlement of Madagascar I The settlement of Madagascar remains problematic, for lack of archaeological sites which clearly point to Austronesian heritage The earliest sites are around 5th century AD and the dating is hardly secure. -

Languages of Indonesia (Sulawesi)

Ethnologue report for Indonesia (Sulawesi) Page 1 of 27 Languages of Indonesia (Sulawesi) See language map. Indonesia (Sulawesi). 14,111,444 (2000 census). 4 provinces. Information mainly from T. Sebeok 1971; J. C. Anceaux 1978; S. Kaseng 1978, ms. (1983); B. H. Bhurhanuddin ms. (1979); J. N. Sneddon 1983, 1989, 1993; C. E. and B. D. Grimes 1987; T. Friberg 1987; T. Friberg and T. Laskowske 1988; R. van den Berg 1988, 1996; M. Martens 1989; N. P. Himmelmann 1990; R. Blust 1991; Noorduyn 1991a; D. E. Mead 1998. The number of languages listed for Indonesia (Sulawesi) is 114. Of those, all are living languages. Living languages Andio [bzb] 1,700 (1991 SIL). Central Sulawesi, Banggai District, Lamala Subdistrict, eastern peninsula, Taugi and Tangeban villages. Alternate names: Masama, Andio'o, Imbao'o. Dialects: Related to Balantak, Saluan. Lexical similarity 44% with Bobongko, 62% with Coastal Saluan, 66% with Balantak. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Sulawesi, Saluan-Banggai, Western More information. Aralle- [atq] 12,000 (1984 SIL). South Sulawesi, Tabulahan Mambi Subdistrict, between Mandar and Kalumpang. Dialects: Aralle, Tabulahan, Mambi. Aralle has 84% to 89% lexical similarity with other dialects listed, 75% to 80% with dialects of Pitu Ulunna Salu, Pannei, Ulumandak. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, Northern, Pitu Ulunna Salu More information. Bada [bhz] 10,000 (1991 SIL). South central portion of central Sulawesi, in 14 villages of Lore Selatan Subdistrict, two mixed villages of Pamona Selatan Subdistrict, four mixed villages of Poso Pesisir Subdistrict, part of Lemusa village in Parigi Subdistrict, and Ampibabo Subdistrict. Ako village is in northern Mamuju District, Pasangkayu Subdistrict. -

(LDPC) of Sulawesi, Indonesia

Noorduyn, J., with René van den Berg. 1993. A language description progress chart (LDPC) of Sulawesi, Indonesia. Unpublished typescript, 15 pp. This unpublished paper is incomplete in places, and should be used accordingly. After the publication of J. Noorduyn’s 1991 A Critical Survey of Studies on the Languages of Sulawesi (Leiden: KITLV Press), the following year René van den Berg sketched out an idea for measuring progress in describing Sulawesi languages, and sent his notes to Noorduyn. Noorduyn enthusiastically adopted the idea, and in 1993 drafted the paper which here follows. Plans to develop the paper toward joint publication, however, were precluded by Noorduyn’s passing in April 1994. 1 A LANGUAGE DESCRIPTION PROGRESS CHART (LDPC) OF SULAWESI, INDONESIA 1. Introduction The vast territorial spread and huge number of the Austronesian languages demands an extraordinary effort of professional linguists to record and describe them exhaustively and suffi- ciently. The size of the task has perceptibly been recognized. The post WWII decades have witnessed a steady increase in specialists engaged in Austronesian language studies, carrying out primary research in the field or in-depth and comparative work in university centres. At the same time the professional understanding of language and the methods of linguistic re- search have vastly increased, and the possibilities for pu- blishing results of linguistic research have grown consider- ably. Accordingly, the number of publications concerning both well-known and newly discovered languages, micro- and macro- subgroups, and specific phenomena in this field of linguistic enterprise have also noticeably increased. The situation here briefly sketched requires that from time to time a stock-taking and evaluation take place of what has been achieved as well as what still remains undone. -

Papers in Western Austronesian Linguistics No. 2

r--------------------.------------------ PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Se�ie� A - No. 33 PAPERS IN 'BORNEO AND WESTERN AUSTRONESIAN LINGUISTICS No.2 by C. Court R.A. Blust F.S. Watuseke Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Court, C., Blust, R. and Watuseke, F. editors. Papers in Western Austronesian Linguistics No. 2. A-33, vi + 138 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1977. DOI:10.15144/PL-A33.cover ©1977 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACI FIC LINGUISTICS is published through the Lingui� �ie Ci4eie 06 Canbe44a and consists of four series: SERIES A - OCCASIONA L PAPERS SERIES B - MONOGRAPHS SERIES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PUB LICATIONS EDITOR: S.A. Wurm. ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton. EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B. Bender, University of Hawaii A. Healey, Summer Institute of Linguistics, New Guinea A. Capell, University of Sydney N.D . Liem, University of Hawaii S. Elbert, University of Hawaii H. McKaughan, University of Hawaii K. Franklin, Summer Institute of Linguistics G.N. O'Grady, University of Victoria, B.C. W.W. Glover, Summer Institute of K. Pike, University of Michigan; Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics G. Grace, University of Hawaii E. Uhlenbeck, University of Leiden ALL CORRESPONDENCE concerning PACIFI C LINGUISTICS, including orders and subscriptions, should be addressed to: The Secretary , PACIFIC LINGUISTICS, Department of·Linguistics , School of Pacific Studies , The Australian National University, Canberra , A.C.T. 26 00 . -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & LR-Upgs of Asia-Pacific

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Least-Reached-UPGs of Asia-Pacific AGWM ed. Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net I give credit & thanks to Asia Harvest & Create International for permission to use their people group photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs of Asia-Pacific (China = separate region & DPG) ASIA-PACIFIC SUMMARY: 3,523 total PG; 830 FR & LR-UPG = Frontier & Least Reached-Unreached People Groups Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net = August, 2020 LR-UPG defin: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commands us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

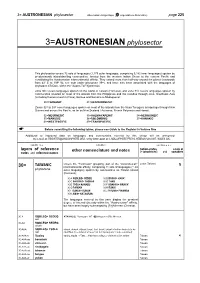

3= AUSTRONESIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 225 3=AUSTRONESIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector covers 72 sets of languages (1,179 outer languages, comprising 3,182 inner languages) spoken by predominantly island-dwelling communities, located from the western Indian Ocean to the eastern Pacific and constituting the Austronesian intercontinental affinity. They extend more than half-way around the planet (eastwards from 43º E to 109º W; see note under phylozone 39=), and have also been associated with the languages of phylozone 47=Daic, within the "Austro-Tai" hypothesis. Zone 30= covers languages spoken on the island of Taiwan (Formosa), and zone 31= covers languages spoken by communities situated on most of the islands from the Philippines and the Celebes through Java, Southeast Asia (including Hainan island in China), Borneo and Sumatra to Madagascar: 30=TAIWANIC 31=HESPERONESIC Zones 32= to 39= cover languages spoken on most of the islands from the Nusa Tenggera archipelago through New Guinea and across the Pacific, as far as New Zealand / Aotearoa, French Polynesia and Hawaii: 32=MESONESIC 33=HALMAYAPENIC 34=NEOGUINEIC 35=MANUSIC 36=SOLOMONIC 37=KANAKIC 38=WESTPACIFIC 39=TRANSPACIFIC Before consulting the following tables, please see Guide to the Register in Volume One Les données supplémentaires -

3=AUSTRONESIAN Phylosector

3= AUSTRONESIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 225 3=AUSTRONESIAN phylosector This phylosector covers 72 sets of languages (1,179 outer languages, comprising 3,182 inner languages) spoken by predominantly island-dwelling communities, located from the western Indian Ocean to the eastern Pacific and constituting the Austronesian intercontinental affinity. They extend more than half-way around the planet (eastwards from 43º E to 109º W; see note under phylozone 39=), and have also been associated with the languages of phylozone 47=Daic, within the "Austro-Tai" hypothesis. Zone 30= covers languages spoken on the island of Taiwan (Formosa), and zone 31= covers languages spoken by communities situated on most of the islands from the Philippines and the Celebes through Java, Southeast Asia (including Hainan island in China), Borneo and Sumatra to Madagascar: 30=TAIWANIC 31=HESPERONESIC Zones 32= to 39= cover languages spoken on most of the islands from the Nusa Tenggera archipelago through New Guinea and across the Pacific, as far as New Zealand / Aotearoa, French Polynesia and Hawaii: 32=MESONESIC 33=HALMAYAPENIC 34=NEOGUINEIC 35=MANUSIC 36=SOLOMONIC 37=KANAKIC 38=WESTPACIFIC 39=TRANSPACIFIC ☛ Before consulting the following tables, please see Guide to the Register in Volume One Additional or improved data on languages and communities covered by this sector will be welcomed by e-mail at: [email protected], or by letter-post at: LINGUASPHERE PRESS, HEBRON SA34 0XT, WALES (UK). COLUMN 1 & 2 COLUMN 3 -

LCSH Section I

I(f) inhibitors I-225 (Colo.) Germany, 1947-1948 USE If inhibitors USE Interstate 225 (Colo.) Subsequent proceedings, Nuremberg War I & M Canal National Heritage Corridor (Ill.) I-244 (Tulsa, Okla.) Crime Trials, case no. 6 USE Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage USE Interstate 244 (Tulsa, Okla.) BT Nuremberg War Crime Trials, Nuremberg, Corridor (Ill.) I-255 (Ill. and Mo.) Germany, 1946-1949 I & M Canal State Trail (Ill.) USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-H-3 (Hawaii) USE Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail (Ill.) I-270 (Ill. and Mo. : Proposed) USE Interstate H-3 (Hawaii) I-5 USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-hadja (African people) USE Interstate 5 I-270 (Md.) USE Kasanga (African people) I-8 (Ariz. and Calif.) USE Interstate 270 (Md.) I Ho Yüan (Beijing, China) USE Interstate 8 (Ariz. and Calif.) I-278 (N.J. and N.Y.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-10 USE Interstate 278 (N.J. and N.Y.) I Ho Yüan (Peking, China) USE Interstate 10 I-291 (Conn.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-15 USE Interstate 291 (Conn.) I-hsing ware USE Interstate 15 I-394 (Minn.) USE Yixing ware I-15 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 394 (Minn.) I-K'a-wan Hsi (Taiwan) USE Polikarpov I-15 (Fighter plane) I-395 (Baltimore, Md.) USE Qijiawan River (Taiwan) I-16 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 395 (Baltimore, Md.) I-Kiribati (May Subd Geog) USE Polikarpov I-16 (Fighter plane) I-405 (Wash.) UF Gilbertese I-17 USE Interstate 405 (Wash.) BT Ethnology—Kiribati USE Interstate 17 I-470 (Ohio and W. -

ISBN 978-602-60218-1-6 1 Kearifan Nusantara

ISBN 978-602-60218-1-6 ANALISIS STRUKTURALISME LEVI-STRAUSS, MITOS, SIMBOL DAN FUNGSI LEGENDA GOA NGERONG DI KECAMATAN RENGEL KABUPATEN TUBAN BAGI MASYARAKAT SEKITARNYA (KAJIAN FOLKLOR) Kiki Astrea Universitas Islam Darul Ulum Lamongan [email protected] Abstract Oral literature is of folklore, a culture, spread by word of mouth. This study attempts to examine the folklore of Ngerong Cave legend located at Rengel, Tuban. This study will describe structure, myth, symbol, and function in the Ngerong Cave legend in a descriptive qualitative approach. The source of data is the society‘s recording around Ngerong Cave, while the data is the written story based on the recording attained from the society around Ngerong Cave. The data collection is obtained through determining the object and doing a recording. Besides, the data analysis techniques gained by processing, collecting the data based on the result of recording, then making a note and presenting the data. The result shows that an emerged myth is the people should not eat the fish obtained from Ngerong Cave because it is considered as a holy fish, whereas the visitors of the cave believe that when they got a fish from the cave, they would get a fortune. Keywords: Strukturalisme Levi-Strauss. Mitos. Simbol. Fungsi. Legenda. Goa Ngerong. Rengel. Tuban. Kajian Folklor. PENDAHULUAN Masyarakat Indonesia mempunyai beragam kebudayaan yang merupakan warisan leluhur dan dilaksanakan secara turun temurun. Salah satu kebudayaan yang masih dilaksanakan sampai saat ini adalah ―adat- istiadat‖ (Purwadi, 2007:12). Adat-istiadat adalah suatu kebiasaan yang dilaksanakan suatu masyarakat. Kebiasaan ini terjadi karena adanya warisan leluhur yang dilaksanakan secara turun-temurun. -

Talaud Verbs: Paradigm of Basic Verbs

Tokyo University Linguistic Papers (TULIP) 33 (2013) 319-361 Talaud Verbs: Paradigm of Basic Verbs Atsuko Utsumi Keywords: Talaud language, Morphology, Verb Paradigm, Sangiric languages, Austronesian languages Abstract The Talaud language is an Austronesian language spoken in North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Talaud verbs are divided into basic verbs which do not take derivational affixes and derivational verbs that take a derivational affix. This paper focuses on paradigm of Talaud basic verbs. Talaud verbs can take up to three grammatical voices, but the number of voice(s) which they can take is determined lexically. Accordingly, Talaud verbs are categorized into single-voiced, double-voiced and triple-voiced verbs. Each category of verb show distinctive semantic features. Paradigm and semantic features of each category of verb are described in detail. 1. Introduction This study examines the paradigm of basic verbs in the Talaud language that belongs to the Sangiric micro-group within the Philippine language group of the Western Malayo-Polynesian languages. The Talaud language is spoken in the Talaud Islands located approximately 200 kms north of Sulawesi Island in Indonesia. Unfortunately, this language is in danger of extinction because people younger than 40 years of age rarely speak the language. The Talaud language has a rich morphology in which affixes attached to the verbs are abundant. In this study, verbs are divided into overall two groups: basic and derivational verbs. Basic verbs are those that do not take derivational affixes, and derivational verbs are those that do take such affixes. Because derivational affixes attached to Talaud verb bases can total seven or more, the paradigm of basic verbs is primarily referred to in this study for simplicity.