Papers in Western Austronesian Linguistics No. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded From

J. Sneddon H. Tadjuddin Usup Shared sound changes in the Gorontalic language group; Implications for subgrouping In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 142 (1986), no: 4, Leiden, 407-426 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 03:48:08PM via free access J. N. SNEDDON and HUNGGU TADJUDDIN USUP SHARED SOUND CHANGES IN THE GORONTALIC LANGU AGE GROUP: IMPLICATIONS FOR SUBGROUPING 1. INTRODUCTION This paper describes sound changes which have occurred within the Gorontalic linguisticgroupof North Sulawesi, Indonesia.1 There are two reasons why such a study is of interest. First, no comparative study of these languages has yet been carried out and information on some of the languages is extremely limited. Secondly, a considerable number of shared sound changes have occurred among the Gorontalic languages which might appear at first to offer good evidence . for subgrouping. However, closer examination shows a rather random distribution of shared changes among the languages such that the evi- dence for subgrouping offered by some innovations conflicts with the equally impressive evidence of other innovations. Further, some lan- guages participated in a number of shared changes while not undergoing chronologically earlier changes. Thus many shared innovations must be the result of areal diffusion among the languages rather than common inheritance. The conflicting evidence for subgrouping presented by the large number of sound changes within the group means that phono- logical changes alone offer no reliable evidence for subgrouping. The Gorontalic languages provide an excellent case of areal spread of sound changes among languages which were once, but in some cases are no longer, geographically contiguous. -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15Th ICAL 2021 WELCOME

15TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON AUSTRONESIAN LINGUISTICS BOOK OF ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15th ICAL 2021 WELCOME The Austronesian languages are a family of languages widely dispersed throughout the islands of The name Austronesian comes from Latin auster ICAL The 15-ICAL wan, Philippines 15th ICAL 2021 ORGANIZERS Department of Asian Studies Sinophone Borderlands CONTACTS: [email protected] [email protected] 15th ICAL 2021 PROGRAMME Monday, June 28 8:30–9:00 WELCOME 9:00–10:00 EARLY CAREER PLENARY | Victoria Chen et al | CHANNEL 1 Is Malayo-Polynesian a primary branch of Austronesian? A view from morphosyntax 10:00–10:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL 2 S2: S1: 10:30-11:00 Owen Edwards and Charles Grimes Yoshimi Miyake A preliminary description of Belitung Malay languages of eastern Indonesia and Timor-Leste Atsuko Kanda Utsumi and Sri Budi Lestari 11:00-11:30 Luis Ximenes Santos Language Use and Language Attitude of Kemak dialects in Timor-Leste Ethnic groups in Indonesia 11:30-11:30 Yunus Sulistyono Kristina Gallego Linking oral history and historical linguistics: Reconstructing population dynamics, The case of Alorese in east Indonesia agentivity, and dominance: 150 years of language contact and change in Babuyan Claro, Philippines 12:00–12:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 12:30–13:30 PLENARY | Olinda Lucas and Catharina Williams-van Klinken | CHANNEL 1 Modern poetry in Tetun Dili CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL -

Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo

Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 1 A’ou [aou] Iouo China 2 Abai Sungai [abf] Iouo Malaysia 3 Abaza [abq] Iouo Russia, Turkey 4 Abinomn [bsa] Iouo Indonesia 5 Abkhaz [abk] Iouo Georgia, Turkey 6 Abui [abz] Iouo Indonesia 7 Abun [kgr] Iouo Indonesia 8 Aceh [ace] Iouo Indonesia 9 Achang [acn] Iouo China, Myanmar 10 Ache [yif] Iouo China 11 Adabe [adb] Iouo East Timor 12 Adang [adn] Iouo Indonesia 13 Adasen [tiu] Iouo Philippines 14 Adi [adi] Iouo India 15 Adi, Galo [adl] Iouo India 16 Adonara [adr] Iouo Indonesia Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Russia, Syria, 17 Adyghe [ady] Iouo Turkey 18 Aer [aeq] Iouo Pakistan 19 Agariya [agi] Iouo India 20 Aghu [ahh] Iouo Indonesia 21 Aghul [agx] Iouo Russia 22 Agta, Alabat Island [dul] Iouo Philippines 23 Agta, Casiguran Dumagat [dgc] Iouo Philippines 24 Agta, Central Cagayan [agt] Iouo Philippines 25 Agta, Dupaninan [duo] Iouo Philippines 26 Agta, Isarog [agk] Iouo Philippines 27 Agta, Mt. Iraya [atl] Iouo Philippines 28 Agta, Mt. Iriga [agz] Iouo Philippines 29 Agta, Pahanan [apf] Iouo Philippines 30 Agta, Umiray Dumaget [due] Iouo Philippines 31 Agutaynen [agn] Iouo Philippines 32 Aheu [thm] Iouo Laos, Thailand 33 Ahirani [ahr] Iouo India 34 Ahom [aho] Iouo India 35 Ai-Cham [aih] Iouo China 36 Aimaq [aiq] Iouo Afghanistan, Iran 37 Aimol [aim] Iouo India 38 Ainu [aib] Iouo China 39 Ainu [ain] Iouo Japan 40 Airoran [air] Iouo Indonesia 1 Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 41 Aiton [aio] Iouo India 42 Akeu [aeu] Iouo China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, -

Research Note

Research Note The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: A Work in Progress Robert Blust and Stephen Trussel UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA AND TRUSSEL SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT The Austronesian comparative dictionary (ACD) is an open-access online resource that currently (June 2013) includes 4,837 sets of reconstructions for nine hierarchically ordered protolanguages. Of these, 3,805 sets consist of single bases, and the remaining 1,032 sets contain 1,032 bases plus 1,781 derivatives, including affixed forms, reduplications, and compounds. His- torical inferences are based on material drawn from more than 700 attested languages, some of which are cited only sparingly, while others appear in over 1,500 entries. In addition to its main features, the ACD contains sup- plementary sections on widely distributed loanwords that could potentially lead to erroneous protoforms, submorphemic “roots,” and “noise” (in the information-theoretic sense of random lexical similarity that arises from historically independent processes). Although the matter is difficult to judge, the ACD, which prints out to somewhat over 3,000 single-spaced pages, now appears to be about half complete. 1. INTRODUCTION. 1 The December 2011 issue of this journal carried a Research Note that described the history and present status of POLLEX, the Polynesian Lexicon project initiated by the late Bruce Biggs in 1965, which over time has grown into one of the premier comparative dictionaries available for any language family or major subgroup (Greenhill and Clark 2011). A theme that runs through this piece is the remark- able growth over the 46 years of its life (at that time), not just in the content of the dictio- nary, but in the technological medium in which the material is embedded. -

Holle Lists: Vocabularies in Languages of Indonesia, Vol. I: Introductory Volume

PACIFIC L1NGUISTICS Se�ie� V - No. 17 HOLLE LISTS: VOCABULARIES IN LANGUAGES OF INDONESIA VOL. 1: INTRODUCTORY VOLUME (MATERIALS IN LANGUAGES OF INDONESIAJ No.1) W.A.L. Stokhof, ed., in cooperation with Lia Saleh-Bronkhorst Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Stokhof, W.A.L. editor. Holle lists: Vocabularies in languages of Indonesia, Vol. I: Introductory volume. D-17, vi + 154 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1980. DOI:10.15144/PL-D17.cover ©1980 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Ling ui�tic Ci�cle 06 Canbe��a and consists of four series: SERIES A - OCCASIONA L PAPERS SERIES B - MONOGRAPHS SERIES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS EDITOR: S.A. Wurm. ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton. EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B. Bender, University of Hawaii J. Lynch, University of Papua New D. Bradley, University of Melbourne Guinea A. Capell, University of Sydney K.A. McElhanon, University of Texas S. Elbert, University of Hawaii H. McKaughan, University of Hawaii K. Franklin, Summer Institute of P. MUhlh�usler, Linacre College, Oxford Linguistics G.N. O'Grady, University of Victoria, W.W. Glover, Summer Institute of B.C. Linguistics A.K. Pawley, University of Hawaii G. Grace, University of Hawaii K. Pike, University of Michigan; Summer M.A.K. Halliday, University of Institute of Linguistics Sydney E.C. Polome, University of Texas A. -

THE STUDY of LINGUISTIC on MINAHASA ETHNIC VOCAL MUSIC Maikel B.G

THE STUDY OF LINGUISTIC ON MINAHASA ETHNIC VOCAL MUSIC Maikel B.G. Sanger Abstrack Some research agree that music is a language, both of which use sound media. The rhythm of language also allows the same rhythm of music for a particular culture language. The Minahasa ethnic group has a diverse array of cultural traditions such as language and culture. This ethnic has a series of language types with each accent or a distinctive intonation that is said to be unique. On the other hand, its distinctive singing tradition is also very united with the people who live in it. If a typical accent is part of the Minahasa language language and the distinctive singing tradition is part of the Minahasa culture, can both be linked? Is the Minahasa way of singing influenced by the accent of the language? By looking at these problems, the researcher wanted to give an idea of how the language relation by way of singing of Minahasa people through the title of Linguistic Review on Minahasa Vocal Music. To answer the problem, the researcher uses the C. Dalhaus method of formal analysis: explains the structure of a work in terms of function and relationship between sections and elements, energetic interpretation: relates to the phase of movement or stretch of the tension, gestalt analysis: view the work as overall, hermeneutics: the interpretation of music in the context of an emotional statement or an external meaning. The research titled Linguistic Review of Minahasa Ethnic Vocal Music is a multi-disciplinary research because it will discuss two different disciplines of language discipline and music science. -

The Minahasan Languages = De Minahasische Talen

The Minahasan languages by Nicolaus Adriani translated by David Mead 2020 Sulang Language Data and Working Papers: Translations from the Dutch, no. 24 Sulawesi Language Alliance http://sulang.org/ SulangTrans024-v1 LANGUAGES Subject language : Tombulu, Tondano, Tonsea, Tonsawang, Tontemboan Language of materials : English DESCRIPTION The author begins this paper with an enumeration of the ten languages spoken within the geographical boundaries of the Minahasan Residency located at the northern tip of Celebes (Sulawesi). Thereafter he concentrates on the five Minahasan languages proper, discussing the basis first for their inclusion in a Philippine language group, and second for their internal division into two groups, one comprising Tombulu’, Tonsea’ and Tondano, the other Tontemboan and Tonsawang. This is followed by a lengthy review of Tontemboan literature, including synopses of a number of folktales. The author considered all five Minahasan languages to be threatened, and closes with an appeal for similar work to be carried out in the other languages. A bibliography comprehensively lists previously published works concerning the Minahasan languages. SOURCE Adriani, N. 1925. De Minahasische talen. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië 81:134–164. Original pagination is indicated by including the page number in square brackets, e.g. [p. 134]. VERSION HISTORY Version 1 [25 September 2020] © 2020 by David Mead All Rights Reserved [p. 134] FROM AND ABOUT THE MINAHASA. III. THE MINAHASAN LANGUAGES. BY DR. N. ADRIANI The Minahasa as a whole, with the islands that belong to it, is not occupied exclusively by the Minahasan languages. Although its territory is already not extensive, it further yields a small part to five non-Minahasan languages: Sangir, Bentenan, Bantik, Ponosakan and Bajo. -

PART I: NAME SEQUENCE Name Sequence

Name Sequence PART I: NAME SEQUENCE A-ch‘ang Abor USE Achang Assigned collective code [sit] Aba (Sino-Tibetan (Other)) USE Chiriguano UF Adi Abaknon Miri Assigned collective code [phi] Miśing (Philippine (Other)) Aborlan Tagbanwa UF Capul USE Tagbanua Inabaknon Abua Kapul Assigned collective code [nic] Sama Abaknon (Niger-Kordofanian (Other)) Abau Abujhmaria Assigned collective code [paa] Assigned collective code [dra] (Papuan (Other)) (Dravidian (Other)) UF Green River Abulas Abaw Assigned collective code [paa] USE Abo (Cameroon) (Papuan (Other)) Abazin UF Ambulas Assigned collective code [cau] Maprik (Caucasian (Other)) Acadian (Louisiana) Abenaki USE Cajun French Assigned collective code [alg] Acateco (Algonquian (Other)) USE Akatek UF Abnaki Achangua Abia Assigned collective code [sai] USE Aneme Wake (South American (Other)) Abidji Achang Assigned collective code [nic] Assigned collective code [sit] (Niger-Kordofanian (Other)) (Sino-Tibetan (Other)) UF Adidji UF A-ch‘ang Ari (Côte d'Ivoire) Atsang Abigar Ache USE Nuer USE Guayaki Abkhaz [abk] Achi Abnaki Assigned collective code [myn] USE Abenaki (Mayan languages) Abo (Cameroon) UF Cubulco Achi Assigned collective code [bnt] Rabinal Achi (Bantu (Other)) Achinese [ace] UF Abaw UF Atjeh Bo Cameroon Acholi Bon (Cameroon) USE Acoli Abo (Sudan) Achuale USE Toposa USE Achuar MARC Code List for Languages October 2007 page 11 Name Sequence Achuar Afar [aar] Assigned collective code [sai] UF Adaiel (South American Indian Danakil (Other)) Afenmai UF Achuale USE Etsako Achuara Jivaro Afghan -

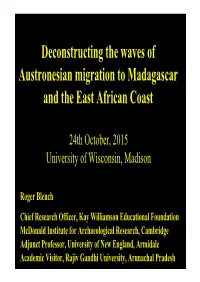

Deconstructing the Waves of Austronesian Migration to Madagascar and the East African Coast

Deconstructing the waves of Austronesian migration to Madagascar and the East African Coast 24th October, 2015 University of Wisconsin, Madison Roger Blench Chief Research Officer, Kay Williamson Educational Foundation McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge Adjunct Professor, University of New England, Armidale Academic Visitor, Rajiv Gandhi University, Arunachal Pradesh What’s the issue I? It has long been accepted (since the 17th century) that Malagasy is an Austronesian language Since Dahl (1960) it has been accepted that the nearest relatives within Austronesian are the Barito languages of SE Borneo However, as we know more about both Malagasy and Bornean languages, it has become increasingly clear the story isn’t as simple as that. Sander Adelaar pointed out some time ago that wind names and many terms to do with seafaring are direct borrowings from Malay Blench (and others) point to the borrowing of natural world terms (especially animal names) from coastal Bantu What’s the issue II? Robert Blust (Austronesian Comparative Dictionary) points out that some Malagasy roots are not attested in Borneo languages Beaujard (in his Tanala dictionary and subsequent papers) identifies a number of roots from Sulawesi languages which are not attested in general Austronesian but which are reconstructed by Mills (1975) All of this points to a specific Sulawesi component Less clear is a Philippines component; Malagasy has a few words which appear to be borrowed from Philippines languages It is also possible these are the result of Iberian trans- Indian Ocean traffic, post 16th century Models for the settlement of Madagascar I The settlement of Madagascar remains problematic, for lack of archaeological sites which clearly point to Austronesian heritage The earliest sites are around 5th century AD and the dating is hardly secure. -

Languages of Indonesia (Sulawesi)

Ethnologue report for Indonesia (Sulawesi) Page 1 of 27 Languages of Indonesia (Sulawesi) See language map. Indonesia (Sulawesi). 14,111,444 (2000 census). 4 provinces. Information mainly from T. Sebeok 1971; J. C. Anceaux 1978; S. Kaseng 1978, ms. (1983); B. H. Bhurhanuddin ms. (1979); J. N. Sneddon 1983, 1989, 1993; C. E. and B. D. Grimes 1987; T. Friberg 1987; T. Friberg and T. Laskowske 1988; R. van den Berg 1988, 1996; M. Martens 1989; N. P. Himmelmann 1990; R. Blust 1991; Noorduyn 1991a; D. E. Mead 1998. The number of languages listed for Indonesia (Sulawesi) is 114. Of those, all are living languages. Living languages Andio [bzb] 1,700 (1991 SIL). Central Sulawesi, Banggai District, Lamala Subdistrict, eastern peninsula, Taugi and Tangeban villages. Alternate names: Masama, Andio'o, Imbao'o. Dialects: Related to Balantak, Saluan. Lexical similarity 44% with Bobongko, 62% with Coastal Saluan, 66% with Balantak. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Sulawesi, Saluan-Banggai, Western More information. Aralle- [atq] 12,000 (1984 SIL). South Sulawesi, Tabulahan Mambi Subdistrict, between Mandar and Kalumpang. Dialects: Aralle, Tabulahan, Mambi. Aralle has 84% to 89% lexical similarity with other dialects listed, 75% to 80% with dialects of Pitu Ulunna Salu, Pannei, Ulumandak. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, Northern, Pitu Ulunna Salu More information. Bada [bhz] 10,000 (1991 SIL). South central portion of central Sulawesi, in 14 villages of Lore Selatan Subdistrict, two mixed villages of Pamona Selatan Subdistrict, four mixed villages of Poso Pesisir Subdistrict, part of Lemusa village in Parigi Subdistrict, and Ampibabo Subdistrict. Ako village is in northern Mamuju District, Pasangkayu Subdistrict. -

Maintaining Minahasan Languages Through Oral Tradition

MAINTAINING MINAHASAN LANGUAGES THROUGH ORAL TRADITION Kevin Yeremia Robot [email protected] Pascasarjana Program Studi Linguistik Universitas Sam Ratulangi Abstract According to Ethnologue, Minahasan languages, such as Tontemboan, Tombulu, Tonsea, Tolour, Tonsawang, Ratahan, Ponosakan, and Bantik are categorized as threatened and even shifting. It means that if there are no actual measures to rejuvenate the languages, it could be foreseen that Minahasan languages will be left with no native speakers. Mainly treated as vernaculars, and with the internalization of Manado Malay as the lingua franca in Minahasa and Indonesian language as the sole official language in Indonesia, both factors gave impact to the condition of Minahasan languages. That being said, in general, Minahasan languages have less prestige than Manado Malay and Indonesian in daily communication in Minahasa. Therefore, in this paper, I would like to argue the importance of language maintenance, especially for endangered languages in Minahasa that such languages should be learned and used by people in Minahasa according to their areas. Moreover, I would explain what are considered to be oral tradition and the previous examples of documented oral tradition in Minahasan languages, then the reason of the importance of oral tradition in language maintenance and language learning. Keywords: Oral Tradition, Minahasan Languages, Language Maintenance INTRODUCTION According to Ethnologue, it is revealed that Minahasan languages, namely Tombulu, Tonsea, Toulour, Tontemboan, Tonsawang, Bantik and Ponosakan, are categorized as level 6b to 8a based on Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (EGIDS). Also, it is said that languages that are included in level 6b and 7 are considered as endangered languages, and in level 8a through 9 are considered as dying languages. -

Malaysia, Ipomoea. Belong with Exceptions Buitenzorg

The Convolvulaceae of Malaysia, III by S.J. van Ooststroom (Rijksherbarium, Leiden) (Issued March 1st, 1940). The genus Ipomoea. subdivided Hallier ²) the Convolvulaceae into two groups, viz. the Psiloconiae, with smooth pollen grains, and the Echinoconiae with spinose Psiloconiae in have been ones. The genera of the occurring Malaysia dealt with in parts I and II of the present paper, with exception of which shall be treated in the genus Erycibe, a special monograph. of Echinoconiae contains viz. 1. The group two tribes, Ipomoeeae in The and 2. Argyreieae, both represented Malaysia. genus Ipomoea belongs to the Ipomoeeae. The materials examined belong with a few exceptions to the herbaria of Buitenzorg (B), Leiden (L), Pasoeroean (Pa), Utrecht (U) and Wageningen (W). It seemed better not to ask for the loan of foreign collections broken of the 1939. during the war, out in the course year XVI. IPOMOEA L. L., Spec. PI. ed. 1 (1753) p. 159; BLUME, Bydr. (1825) p. 708; CHOKY in Mem. Soc. Geneve VI id. in Mem. Soc. Phys. (1833) p. 444; Geneve VIII id. in Prodr. IX Phys. (1838) p. 52; DC., (1845) p. 348; PI. Ned. Ind. PI. IV MIQ., II (1857) p. 601; BENTH., Austr. (1869) p. 412; BENTH. & HOOK., Gen. Plant. II (1876) p. 870; CLARKE in PI. Brit. Ind. IV Hist. PI. X IIOOK., (1883) p. 196; BAILLON, (1891) Pfl. p. 321; PETER in ENGL. & PRANTL, Nat. fam. IV, 3a (1891) p. 28; II in Blumea ') Part I in Blumea III, 1 (1938) p. 62—94; part III, 2 (1939) p. 267—371.