S Early Years in Satsuma*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Saint Francis Xavier and the Shimazu Family

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal López-Gay, Jesús Saint Francis Xavier and the Shimazu family Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, núm. 6, june, 2003, pp. 93-106 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36100605 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2003, 6, 93-106 SAINT FRANCIS XAVIER AND THE SHIMAZU FAMILY Jesús López-Gay, S.J. Gregorian Pontifical University, Rome Introduction Exactly 450 years ago, more precisely on the 15th of August 1549, Xavier set foot on the coast of Southern Japan, arriving at the city of Kagoshima situated in the kingdom of Satsuma. At that point in time Japan was politically divided. National unity under an Emperor did not exist. The great families of the daimyos, or “feudal lords” held sway in the main regions. The Shimazu family dominated the region of Kyúshú, the large island in Southern Japan where Xavier disembarked. Xavier was accompa- nied by Anjiró, a Japanese native of this region whom he had met in Malacca in 1547. Once a fervent Buddhist, Anjiró was now a Christian, and had accompanied Xavier to Goa where he was baptised and took the name Paulo de Santa Fé. Anjiró’s family, his friends etc. helped Xavier and the two missionaries who accompanied him (Father Cosme de Torres and Brother Juan Fernández) to instantly feel at home in the city of Kagoshima. -

A New Interpretation of the Bakufu's Refusal to Open the Ryukyus To

Volume 16 | Issue 17 | Number 3 | Article ID 5196 | Sep 01, 2018 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus A New Interpretation of the Bakufu’s Refusal to Open the Ryukyus to Commodore Perry Marco Tinello Abstract The Ryukyu Islands are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to In this article I seek to show that, while the Taiwan. The former Kingdom of Ryukyu was Ryukyu shobun refers to the process by which formally incorporated into the Japanese state the Meiji government annexed the Ryukyu as Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. Kingdom between 1872 and 1879, it can best be understood by investigating its antecedents in the Bakumatsu era and by viewing it in the wider context of East Asian and world history. I show that, following negotiations with Commodore Perry, the bakufu recognized the importance of claiming Japanese control over the Ryukyus. This study clarifies the changing nature of Japanese diplomacy regarding the Ryukyus from Bakumatsu in the late 1840s to early Meiji. Keywords Tokugawa bakufu, Bakumatsu, Ryukyu shobun, Commodore Perry, Japan From the end of the fourteenth century until the mid-sixteenth century, the Ryukyu kingdom was a center of trade relations between Japan, China, Korea, and other East Asian partners. According to his journal, when Commodore Matthew C. Perry demanded that the Ryukyu Islands be opened to his fleet in 1854, the Tokugawa shogunate replied that the Ryukyu Kingdom “is a very distant country, and the opening of its harbor cannot be discussed by us.”2 The few English-language studies3 of this encounter interpret this reply as evidence that 1 16 | 17 | 3 APJ | JF the bakufu was reluctant to become involved in and American sources relating to the discussions about the international status of negotiations between Perry and the bakufu in the Ryukyus; no further work has been done to 1854, I show that Abe did not draft his guide investigate the bakufu’s foreign policy toward immediately before, but rather after the Ryukyus between 1854 and the early Meiji negotiations were held at Uraga in 1854/2. -

Spring Summer Autumn Winter

Rent-A-Car und Kagoshi area aro ma airpo Recommended Seasonal Events The rt 092-282-1200 099-261-6706 Kokura Kokura-Higashi I.C. Private Taxi Hakata A wide array of tour courses to choose from. Spring Summer Dazaifu I.C. Jumbo taxi caters to a group of up to maximum 9 passengers available. Shin-Tosu Usa I.C. Tosu Jct. Hatsu-uma Festival Saga-Yamato Hiji Jct. Enquiries Kagoshima Taxi Association 099-222-3255 Spider Fight I.C. Oita The Sunday after the 18th day of the Third Sunday of Jun first month of the lunar calendar Kurume I.C. Kagoshima Jingu (Kirishima City) Kajiki Welfare Centre (Aira City) Spider Fight Sasebo Saga Port I.C. Sightseeing Bus Ryoma Honeymoon Walk Kirishima International Music Festival Mid-Mar Saiki I.C. Hatsu-uma Festival Late Jul Early Aug Makizono / Hayato / Miyama Conseru (Kirishima City) Tokyo Kagoshima Kirishima (Kirishima City) Osaka (Itami) Kagoshima Kumamoto Kumamoto I.C. Kirishima Sightseeing Bus Tenson Korin Kirishima Nagasaki Seoul Kagoshima Festival Nagasaki I.C. The “Kirishima Sightseeing Bus” tours Late Mar Early Apr Late Aug Shanghai Kagoshima Nobeoka I.C. Routes Nobeoka Jct. M O the significant sights of Kirishima City Tadamoto Park (Isa City) (Kirishima City) Taipei Kagoshima Shinyatsushiro from key trans portation hubs. Yatsushiro Jct. Fuji Matsuri Hong Kong Kagoshima Kokubu Station (Start 9:00) Kagoshima Airport The bus is decorated with a compelling Fruit Picking Kirishima International Tanoura I.C. (Start 10:20) design that depicts the natural surroundings (Japanese Wisteria Festival) Music Festival Mid-Apr Early May Fuji (Japanese Wisteria) Grape / Pear harvesting (Kirishima City); Ashikita I.C. -

Chapter 1. Meiji Revolution: Start of Full-Scale Modernization

Seven Chapters on Japanese Modernization Chapter 1. Meiji Revolution: Start of Full-Scale Modernization Contents Section 1: Significance of Meiji Revolution Section 2: Legacies of the Edo Period Section 3: From the Opening of Japan to the Downfall of Bakufu, the Tokugawa Government Section 4: New Meiji Government Section 5: Iwakura Mission, Political Crisis of 1873 and the Civil War Section 6: Liberal Democratic Movement and the Constitution Section 7: End of the Meiji Revolution It’s a great pleasure to be with you and speak about Japan’s modernization. Japan was the first country and still is one of the very few countries that have modernized from a non-Western background to establish a free, democratic, prosperous, and peace- loving nation based on the rule of law, without losing much of its tradition and identity. I firmly believe that there are quite a few aspects of Japan’s experience that can be shared with developing countries today. Section 1: Significance of Meiji Revolution In January 1868, in the palace in Kyoto, it was declared that the Tokugawa Shogunate was over, and a new government was established under Emperor, based on the ancient system. This was why this political change was called as the Meiji Restoration. The downfall of a government that lasted more than 260 years was a tremendous upheaval, indeed. It also brought an end to the epoch of rule by “samurai,” “bushi” or Japanese traditional warriors that began as early as in the 12th century and lasted for about 700 years. Note: This lecture transcript is subject to copyright protection. -

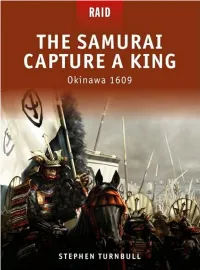

Raid 06, the Samurai Capture a King

THE SAMURAI CAPTURE A KING Okinawa 1609 STEPHEN TURNBULL First published in 2009 by Osprey Publishing THE WOODLAND TRUST Midland House, West Way, Botley, Oxford OX2 0PH, UK 443 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016, USA Osprey Publishing are supporting the Woodland Trust, the UK's leading E-mail: [email protected] woodland conservation charity, by funding the dedication of trees. © 2009 Osprey Publishing Limited ARTIST’S NOTE All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private Readers may care to note that the original paintings from which the study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, colour plates of the figures, the ships and the battlescene in this book Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be were prepared are available for private sale. All reproduction copyright reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by whatsoever is retained by the Publishers. All enquiries should be any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, addressed to: photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers. Scorpio Gallery, PO Box 475, Hailsham, East Sussex, BN27 2SL, UK Print ISBN: 978 1 84603 442 8 The Publishers regret that they can enter into no correspondence upon PDF e-book ISBN: 978 1 84908 131 3 this matter. Page layout by: Bounford.com, Cambridge, UK Index by Peter Finn AUTHOR’S DEDICATION Typeset in Sabon Maps by Bounford.com To my two good friends and fellow scholars, Anthony Jenkins and Till Originated by PPS Grasmere Ltd, Leeds, UK Weber, without whose knowledge and support this book could not have Printed in China through Worldprint been written. -

Chapter 4: Modern Japan and the World (Part 1) – from the Final Years of the Edo Shogunate to the End of the Meiji Period

| 200 Chapter 4: Modern Japan and the World (Part 1) – From the Final Years of the Edo Shogunate to the End of the Meiji Period Section 1 – The encroachment of the Western powers in Asia Topic 47 – Industrial and people's revolutions | 201 What events led to the birth of Europe's modern nations? People's revolutions The one hundred years between the late-seventeenth and late-eighteenth centuries saw the transformation of Europe's political landscape. In Great Britain, the king and the parliament had long squabbled over political and religious issues. When conflict over religious policies intensified in 1688, parliament invited a new king from the Netherlands to take the throne. The new king took power without bloodshed and sent the old king into exile. This event, known as the Glorious Revolution, consolidated the parliamentary system and turned Britain into a constitutional monarchy.1 *1=In a constitutional monarchy, the powers of the monarch are limited by the constitution and representatives chosen by the citizens run the country's government. Great Britain's American colonies increasingly resisted the political repression and heavy taxation imposed by their king, and finally launched an armed rebellion to achieve independence. The rebels released the Declaration of Independence in 1776, and later enacted the Constitution of the United States, establishing a new nation with a political system based on a separation of powers.2 *2=Under a separation of powers, the powers of the government are split into three independent branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. In 1789, an angry mob of Parisian citizens, who groaned under oppressively heavy taxes, stormed the Bastille Prison, an incident that sparked numerous rural and urban revolts throughout France against the king and the aristocracy. -

Anglo-Satsuma

CHAPTER THREE ESTABLISHMENT AND GROWTH OF HOLME, RINGER & CO. The ‘Anglo-Satsuma War’ of 1863 was a brief but bloody clash between the British government and the Satsuma domain (present-day Kagoshima Prefecture) over the murder of Charles L. Richardson, a Shanghai mer- chant who had interfered with the train of the daimyo of Satsuma on a country road near Yokohama and suffered a gory death at the hands of the daimyo’s retainers the previous year. The Tokugawa Shogunate, anxious to avoid a confrontation, submitted a formal apology and offered an indem- nity of 10,000 pounds. The Satsuma domain, however, refused to either apologise or pay an indemnity, insisting that Richardson had been at fault by failing to pay proper respect. The British rebutted by pointing to the guarantee of extraterritoriality embedded in the Ansei Treaty, which they said exonerated Richardson of any wrongdoing. The suspense rose to a climax in August 1863 when the British despatched seven warships to Kagoshima and submitted a set of demands directly to the leaders of the domain. The Satsuma shore batteries opened fire, and the British warships promptly retaliated, destroying three steamships anchored in the harbour and inflicting damage on the city. The gunfire from the Japanese mean- while resulted in the death of several British personnel, including the commander of one of the warships. Satsuma was one of the wealthiest and most powerful domains in Japan, its territories sprawling over a large section of southern Kyūshū and its influence extending to the Ryūkyū Islands (present-day Okinawa Prefecture) to the southwest. -

Winds Over Ryukyu. a Narrative on the 17Th Century Ryukyu Kingdom

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository Mikołaj Melanowicz Winds over Ryukyu . A Narrative on the 17th Century Ryukyu Kingdom Introduction A historical drama ( taiga dorama 大河ドラマ), broadcast by Japanese public television NHK about the Ryukyu Kingdom – the present Okinawa prefecture – was an important event which brought back to life things that many Japanese would prefer to remain concealed. The story concerns the history of the Ryukyu Kingdom’s subjugation by the Japanese in the seventeenth century. Before that time, the Ryukyu Kingdom had maintained trade relations with China, the Philippines, Japan and even South-East Asia. It was a period of prosperity stretching over the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the time when the kingdom was united and strengthen. The TV series was based on the novel Ryūkyū no kaze (Winds over Ryukyu, 1992), by Chin Shunshin, a well-known writer of Chinese origin. The novel is 900 pages long and divided into three volumes: Dotō no maki ( 怒涛の巻: ’the book of angry waves’), Shippū no maki ( 疾風の 巻 雷雨の巻 : ‘the book of the violent1 wind’), and Raiu no maki ( : ‘the book of the thunderstorm’) . These titles reflect the increasing danger faced by the heroes of the novel and the 100,000 inhabitants of the archipelago. The danger comes from the north, from the Japanese island of Kyushu, the south-eastern part of which was governed by a clan from Satsuma ( 薩摩, present Kagoshima 鹿児島). The Characters of Winds over Ryukyu The heroes of the novel are two fictional brothers: Keitai, who pursues a political career, and Keizan, who devotes himself to the art of dance in its native form; and their girlfriends, future wives, Aki and Ugi. -

SATSUMA STUDENTS DISPATCH PROJECT: Simultaneously

SATSUMA STUDENTS DISPATCH PROJECT: Kagoshima Prefecture Simultaneously promoting “Global Human Resources Training for Young People”, “Cultivation of a Love of Hometown”, and “International Exchange with the UK” using the great achievements of our predecessors as a springboard Background to the Project with local young people, thereby vicariously Global human resources training coming experiencing the efforts and achievements of out of Kagoshima, the region that built the their predecessors. foundation for modern Japan 1. Dispatch Destination: UK (Camden Borough Kagoshima Prefecture is the home of Saigo in London, Manchester, etc.) Takamori and Okubo Toshimichi, statesmen 2. No. of Tour Participants: 19 (15 high school who made great achievements in the students and 4 chaperones) establishment of the Meiji Restoration—the 3. Dispatch Period: 28th July (Sat) – 6th August foundation of modern Japan. With 2018 (Mon), 2018 marking the 150th anniversary of the Meiji 4. Programme Details Restoration, to strengthen initiatives such as (1) Visits to University College London relaying Kagoshima’s appeal to the world and (UCL)2 and other sites training human resources who will become (2) Local activities (following the footsteps future leaders, Kagoshima Prefecture, of the Satsuma Students, courtesy calls tourism industry related enterprises, and to Camden Council Office and other economic organisations have joined together related organisations, tours of cutting- to establish the “Meiji Restoration 150th edge fields led by the UK, exchange Anniversary -

Creating Heresy: (Mis)Representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-Ryū

Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Takuya Hino All rights reserved ABSTRACT Creating Heresy: (Mis)representation, Fabrication, and the Tachikawa-ryū Takuya Hino In this dissertation I provide a detailed analysis of the role played by the Tachikawa-ryū in the development of Japanese esoteric Buddhist doctrine during the medieval period (900-1200). In doing so, I seek to challenge currently held, inaccurate views of the role played by this tradition in the history of Japanese esoteric Buddhism and Japanese religion more generally. The Tachikawa-ryū, which has yet to receive sustained attention in English-language scholarship, began in the twelfth century and later came to be denounced as heretical by mainstream Buddhist institutions. The project will be divided into four sections: three of these will each focus on a different chronological stage in the development of the Tachikawa-ryū, while the introduction will address the portrayal of this tradition in twentieth-century scholarship. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………………...ii Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………….………..vi Preface…………………………………………………………………………………………...vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…………….1 Chapter 1: Genealogy of a Divination Transmission……………………………………….……40 Chapter -

Sino-Japanese Relations in the Edo Period •

• Period Edo Sino-Japanese the in Relations C)ba • )'•. Osamu • University Kansai Fogel by A. Joshua Translated Sino-Japanese Contacts Forgotten One. Part general historical The Research. Knowledge Historical and General Historical nearly history for teaching suspicious. knowledge highly have been is I now possess we frequently settle cold in break I it but when think back I 30 I sweat. out on a years, a over knowledge general of points topic of doubt in research when locate I my own some discussing theme proudly Right of in middle history begin the them. and a to pursue surface. the rise suddenly doubts shudder office, clearly understood in I which I to as my Seinan of the War end time of the example, about the hundred For ago years was one Michinaga Fujiwara •-• N roughly 2 of the time thousand (1877), and years ago was one •}[ • • IN (1827-77) and )• •,• -•: N Saig6 Takamori that (966-1027). know We really do but clearly from different Fujiwara Michinaga from own, we our ages were men Michinaga? In and Takamori between good of of difference 900 have the years a sense remain holes Kagoshima, bullet the private school in of walls of the ruins the the stone • Yorimichi -•4• •: Michinaga's by complex By6d6in temple built fresh. The son, via these mind these beauty. call When with I still the its two two to great arrests men eye longer strikes Takamori the relics, from historical the hundred present to as me years one Michinaga. Takamori and intervening between the than 900 years :f• • [Hebei], unearthed Mancheng though, tombs token, the the By Han at same Changxin Palace the look B.C.E., but when built around 1968, in 112 at you were being from the •' of site, has the dug burial it the which Lantern appearance at up was problems ,• • though there Yayoi Japan's Even of earthenware are era. -

The Catholic Church in Japan

• Tht CATHOLIC CHURCHin JAPAN The CATHOLIC Here, with all of its colorful pagentry, its HUllCHin JAPAN bloody martyrdoms, its heart-breaking failures and its propitious successes, is the history of the fust Christian Missionaries in Japan. Johannes Laures, the well-known Jesuit au thority on the Catholic Mission in Japan, has here re-created in all of its splendor the long, bitter and bloody battle of this first Christian Church. From its beginnings to its present eminence Father Laures has traced this. hitherto confusing history, pausing now and again to create for the reader the personality of a great Christian leader or a notable Japanese daimyo. This work, scholarly without being dull, fast reading without being light, is a history of the History greatest importance to all tho_se interested in Japan. More, it is the inspiring story of the triumph of the Christian faith. by Charles E. TuttleCo .. Publishtrs .," ..,, "'z a: 0 Ianm d, JiUfRcgMn t a/.r , f<•.m,,;,,/iufc., ta. tft f,'d,sc ltf,f/«,, lu.bo ',t lrtdw(l'r,a _;,�rvrw"1 ..1• 1 R,I Oildat, ' �V m .. , ... c�. 1„n„ Cllf•,iu,,w ,, ,., : """'"""'n.t,,,r 1-iub u.tSv-,e /1.lk vd ,,.(.,(enrnb• U, CnlJ i;, fo, Rt l,nr -,.,n,tNS,U cf'iomI r. 1 6f Sem,n„ 'm I ri Xf� 1rtodOrt ID!t:S oppeta, .. t, ,., ------' . ,.,, Th� O�tho:tilc Chürch i!n Jap1arr .., The Catholic Church in Japan A Short History by Johannes Laures, S. J. CHARLES E. TUTTLE COMPANY Rutland, Vermont Tokyo, Japan Saint Frands Preacbing to the Japanese an imaginary portrait Published by the Charles E.