Whites W/O College Degrees in SS Presidential Policy Spills Over And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Months to Go: Where the Presidential Contest Stands As the General Election Begins

May 10, 2012 Six Months To Go: Where the Presidential Contest Stands as the General Election Begins William A. Galston Table of Contents Summary 1 Where We Are Now and How We Got There 1 The Mood of the Country 3 The Issues 5 Ideology 7 What Kind of Election Will 2012 Be? 9 Referendum or Choice? 9 Persuasion or Mobilization? 13 It’s the Electoral College, Stupid 16 Conclusion: The Known Unknowns 22 Endnotes 23 SUMMARY arack Obama’s standing with the American people hit bottom in the late Bsummer and early fall of 2011. Since then, the president has recovered the political ground he lost during the debt ceiling fiasco and now enjoys a narrow edge over Mitt Romney, the presumptive Republican nominee. The standard political and economic indicators suggest that the 2012 election will be close. And the historic level of partisan polarization ensures that it will be hard-fought and divisive. William A. Galston is the Ezra K. Zilkha Since Vietnam and the Iranian hostage crisis, Republicans have effectively used the Chair in Governance issue of national security against Democrats. Barring unforeseen events, Romney Studies and senior will not be able to do so this year. Nor will a focus on hot-button social issues yield fellow at Brookings. significant gains for the challenger. Instead, to an extent that Americans have not seen for at least two decades, the election of 2012 will revolve around a single defining issue—the condition of the economy. In 2008, Barack Obama defeated John McCain in large measure because the people saw him as more able to manage the economy at a moment of frightening crisis. -

President Trump and America's 2020 Presidential Election

President Trump And America’s 2020 Presidential Election: An Analytical Framework March 6, 2019 © 2019 Beacon Policy Advisors LLC Trump 2020 Meets Trump 2016 ___________________________________________________________ Trump 2020 Is A Stronger Candidate Than Trump 2016… • Looking purely at Trump’s personal standing in 2016 vs. 2020, he is no worse for wear, with the greatest change in his ratings coming from the consolidation of support among Republicans after two years of providing wins for his GOP base (e.g., deregulation, conservative judges) and currently having a strong economy and jobs market …But Trump 2016 Was A Weak Candidate (Who Happened To Face Another Weak Candidate) • Trump vs. Clinton 2016 matchup had the two most unfavorable candidates in a 60-year span • According to the 2016 exit polls, 18 percent of voters who had an unfavorable view of both Clinton and Trump voted for Trump by a 17- point margin – those margins were even higher in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Florida • Trump was the “change” candidate, winning voters who wanted change by a 68-point margin • Still, Trump only garnered 46.1 percent of the popular vote © 2019 Beacon Policy Advisors LLC 1 Trump’s Base Not Enough To Win ___________________________________________________________ Trump Is A Strong Weak Incumbent Heading Into 2020 Election • Trump’s political base of support – “America First” nationalists, rural farmers, and evangelical Christians – was necessary but insufficient to win in 2016 – will still be insufficient to win in 2020 • Trump’s -

Texas and Ohio: the End of the Beginning, but Not the Beginning of the End John C

The End of the Beginning, But Not the Beginning of the End DGAPstandpunkt Washington Briefing Prof. Dr. Eberhard Sandschneider (Hrsg.) März 2008 N° 4 Otto Wolff-Direktor des Forschungsinstituts der DGAP e. V. ISSN 1864-3477 Texas and Ohio: The End of the Beginning, But Not the Beginning of the End John C. Hulsman Hillary Clinton hat sich mit den Vorwahlsiegen in Ohio und Texas einen Namen als Harry Houdini im ame- rikanischen Wahlkampf gemacht. Die scheinbar unaufhaltbare Nominierung von Barack Obama durch die Demokraten nach elf siegreichen Vorwahlen in Folge ist gestoppt. Für dieses Zauberkunststück hat Clinton sich nicht gescheut, eine Negativkampagne gegen den Konkurrenten aus dem eigenen Lager zu starten: Obama wird dabei immer wieder als unzuverlässiges Leichtgewicht in Fragen der nationalen Sicherheit hingestellt. Das fortge- setzte Kopf-an-Kopf-Rennen macht es für beide Kandidaten schwierig, die notwendige Anzahl von Delegierten für die Nominierung zu erringen. Diese Unentschiedenheit schadet den Demokraten enorm und spielt direkt in die Hände der Republikaner. Following supposedly pivotal Super Tuesday in early more often than Dracula). Stories appeared about the February, something rather surprising happened in disarray in her campaign, how they had blown through this roller-coaster of an election campaign: the Demo- $120 million dollars with precious little to show for it. crats seemed, at long last, to have decisively moved Why these folks had not even thought about a post- toward one of the party’s candidates. Barack Obama Super Tuesday strategy, so confident were they that won 11 straight contests, often by decisive margins. Hillary would lock up the nomination by then. -

2008 Democratic National Convention Brainroom Briefing Book

2008 Democratic National Convention Brainroom Briefing Book 1 Table of Contents CONVENTION BASICS ........................................................................................................................................... 3 National Party Conventions .................................................................................................................................. 3 The Call................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Convention Scheduling......................................................................................................................................... 3 What Happens at the Convention......................................................................................................................... 3 DEMOCRATIC CONVENTIONS, 1832-2004........................................................................................................... 5 CONVENTION - DAY BY DAY................................................................................................................................. 6 DAY ONE (August 25) .......................................................................................................................................... 6 DAY TWO (August 26).......................................................................................................................................... 7 The Keynote Address....................................................................................................................................... -

PS 202 Summer 18 Week 5

PolS 202: Intro to American Politics Stephanie Stanley Week 5: Elections Agenda • Primary Election • Party Nominations • General Election/ Electoral College • Money in Elections • Citizens United and SuperPACS Pre-Gaming • “Green Primary” – Look for donors and sponsors – Party Insiders • File paperwork • Establish campaign – Hire personnel – Work out initial strategies – Announce candidacy It’s a Numbers Game Super-delegates: Democratic party, 716 unpledged delegates, made up of elected officials and party leaders Primaries and Caucuses • 2 ways to get delegates – Primary: direct, statewide process of selecting candidates; voters cast secret ballots for candidates; run by the state • Open Primaries: all registered voters may participate • Closed Primaries: voters may only vote for candidates from the party with which they are registered – Caucus: allows participants to support candidates openly, typically by hand raising or breaking out into groups, run by the party Super Tuesday • About ½ of the GOP delegates and about a 1/3 of the Democratic delegates are up for grabs • Primaries – Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, and Virginia • Caucuses – Colorado, Minnesota, Alaska (GOP only), Wyoming (GOP only), American Samoa (Dems only) Winning Delegates • Proportional – Most states will award delegates proportionally • Winner take all – Some states give all their delegates to the winner • Bounded/pledged delegates – At least during the first round of voting at the party convention, these delegates -

Swing States, the Winner-Take-All Electoral College, and Fiscal Federalism

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Swing States, The Winner-Take-All Electoral College, and Fiscal Federalism Duquette, Christopher and Mixon, Franklin and Cebula, Richard The MITRE Corporation, Columbus State University, Jaclsonville University 9 February 2013 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/55423/ MPRA Paper No. 55423, posted 27 Apr 2014 01:16 UTC Swing States, the Winner-Take-All Electoral College, and Fiscal Federalism by Christopher M. Duquettea, Franklin G. Mixon, Jr.b, and Richard J. Cebulac a The MITRE Corporation, McLean, VA 22102 – USA; b D. Abbott Turner College of Business, Columbus State University, Columbus, GA 31907 – USA; c Davis College of Business, Jacksonville University, Jacksonville, FL 32211 – U.SA. Corresponding Author: Richard J. Cebula, Davis College of Business, Jacksonville University, Jacksonville, FGL 32211 – USA. PH: 912-656-2997; FAX: 904-256-7467. E-mail: dr.richardcebula@gmailcom Abstract. There is a debate regarding the impact of swing or independent voters in American politics. While some argue that swing voters either do not swing or have a marginal impact on campaigns, the decline in voter partisan identification and the rise of independents means that they have a potential impact on elections, making them a desirable commodity to candidates. Additionally, presidential elections represent a unique case for swing voters. A robust literature notes that during the presidential primary and caucus process, voters in states such as Iowa or New Hampshire effectively have a greater voice in the election than those in other states. This is due to the number of voters in these states, and the strategic importance of having their primaries and caucuses positioned at the beginning of the presidential selection process. -

Download Article (PDF)

INTERMISSION ENDS The Rhodes Cook Letter February 2012 The Rhodes Cook Letter FEBRUARY 2012 / VOL. 13, NO. 1 (ISSN 1552-8189) Contents Intermission Ends ............................... .3 Chart & Map: 2012 Republican Primary, Caucus Results . 4 Chart & Map: The Road Ahead: The Remaining 2012 GOP Primary, Caucus Calendar . 5 Chart: Aggregate 2012 Republican Vote. 6 Chart & Line Graph: 2012 Republican Delegate Count. 7 Chart & Line Graph: Cumulative 2012 Republican Primary Vote . 8 Chart: The 2012 GOP ‘Medal’ Count. 8 Chart: The Dwindling GOP Field. 9 Results of Early Events ......................... 10 The Santorum Surge: ‘He Cares Enough to Come’. 10 Chart & Map: Iowa Republican Precinct Caucuses . 10 Chart & Map: New Hampshire Republican Primary. 11 Chart & Map: South Carolina Republican Primary. 12 Chart & Map: Florida Republican Primary. 13 Caucus Problems: The Iowa Reversal . 13 Chart & Map: 2012 Republican Primary, Caucus Turnout: A Mixed Bag. 14 Chart & Bar Graph: The Second Time Around: Romney and Paul . 15 On the Democratic Side ........................ 16 Chart & Bar Graph: ‘Unopposed’ Presidents in the New Hampshire Primary. 16 Chart: 2012 Democratic Primary, Caucus Results . 17 Chart & Bar Graph: How Obama Compares to Recent Presidents: The Economy and the Polls . 18 For the Record ............................. 19 Chart: 2012 Congressional Primary Calendar . 19 Chart: The Changing Composition of the 112th Congress . 20 Chart & Maps: What’s Up in 2012 . 21 Subscription Page .............................. .23 To reach Rhodes Cook: Office Phone: 703-658-8818 / E-mail: [email protected] / Web: www.rhodescook.com “The Rhodes Cook Letter” is published on a bimonthly basis. An individual subscription for six issues is $99. Make check payable to “The Rhodes Cook Letter” and mail it, along with your e-mail address, to P.O. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Swing State by Steve Milton

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Swing State by Steve Milton Which Swing States Will Decide the Election? The 2020 presidential race is a seemingly inexhaustible source of emotional turmoil. But how much actual electoral turmoil is going on? The polling has made it clear that most of the contest is not really in doubt: Joe Biden is going to hold onto most of Hillary Clinton’s share of the map from 2016, and Donald Trump is going to hold onto the majority of the states he won. So the Slate Swing State Tracker is here to look at the smaller part of the big picture: How many of the genuinely contested states would each candidate have to win to hit 270 electoral votes, and what does this week’s polling say about their chances? For the purposes of this analysis, we’re assuming there are already 228 electoral votes locked into Biden’s column, and 163 in Trump’s. We’re setting aside the two single electoral votes up for grabs under Nebraska and Maine’s district system. That leaves 10 all-or-nothing battleground states in play. Where do the two campaigns stand? You only need a couple of good polls for Trump in a week to terrify every Democrat in the country. And so there were, exactly, a couple. Battleground polls from ABC News/The Washington Post showed Trump leading Biden by four points in Florida, which has tightened over the last month, and by one point in Arizona, the first lead Trump has posted in a nonpartisan poll of the state in months. -

Election Outcomes You’Re Not Watching

ACCESS A BROADER MARKET PERSPECTIVE ELECTION OUTCOMES YOU’RE NOT WATCHING BY DANIEL TENENGAUZER AND JOHN VELIS HIGHLY DIVIDED ELECTORATE AND WIDE POLICY DIVERSION between Republicans/Democrats, as well as within the Democrats themselves MARKETS ARE PRICING IN A TRUMP OR BIDEN WIN, but Biden may not get the nomination easily or early enough POSSIBILITY OF A BROKERED CONVENTION IN JULY if no Democrat has sufficient delegates THE EARLY PRIMARIES ARE KEY: first few races in the past have predicted the ultimate winner The next administration of either party could be A SOURCE OF POLICY RISK Divided government is NO GUARANTEE OF MARKET- FRIENDLY POLICIES COVER ILLUSTRATION: ROB DOBI INVESTOR CONFIDENCE IS HIGH AHEAD OF THIS NOVEMBER’S PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION. BUT WITH A HIGHLY DIVIDED ELECTORATE AND PLENTY OF ROOM FOR AN UPSET, MARKETS SHOULD BE WARY OF COMPLACENCY BY DANIEL TENENGAUZER AND JOHN VELIS, BNY MELLON MARKETS ith the 2020 US These moves reflect solid US funda- Many of the Democratic policy plans primary election mentals, particularly compared with are meant to help address the income season soon upon the rest of the world; an elongation of gap and Trump as well is more populist W us, investors are the US economic recovery, in part due than previous Republican presidents. faced with potentially market-moving to Trump’s corporate tax cuts; and a This sets up the potential for a larger outcomes in the next 12 months. rebooted and accelerated US labor US deficit, the fallout from which could One thing is clear: despite Donald market. affect market confidence. -

Swing State/Battleground State: in Presidential Elections, States That Do Not Consistently Vote for Either the Democratic Or Republican Presidential Candidate

20th/Raffel The Electoral College (as of the 2010 Census) # # # STATE VOTES STATE VOTES STATE VOTES Alabama 9 Kentucky 8 North Dakota 3 Alaska 3 Louisiana 8 Ohio* 18 Arizona 11 Maine 4 Oklahoma 7 Arkansas 6 Maryland 10 Oregon 7 California 55 Massachusetts 11 Pennsylvania 20 Colorado* 9 Michigan 16 Rhode Island 4 Connecticut 7 Minnesota 10 South Carolina 9 Delaware 3 Mississippi 6 South Dakota 3 District of 3 Missouri 10 Tennessee 11 Columbia Florida* 29 Montana 3 Texas 38 Georgia 16 Nebraska 5 Utah 6 Hawaii 4 Nevada* 6 Vermont 3 Idaho 4 New 4 Virginia* 13 Hampshire* Illinois 20 New Jersey 14 Washington 12 Indiana* 11 New Mexico 5 West Virginia 5 Iowa* 6 New York 29 Wisconsin* 10 Kansas 6 North 15 Wyoming 3 Carolina* From the Chart: 1. Which state has the most electoral votes? How many? 2. Identify the states that have just three votes. 3. How many votes does Massachusetts have? From the Reading (use a separate sheet of paper): 4. What is the difference between the popular vote and the electoral vote? 5. How do most states award their electoral votes? 6. What is a major potential problem with the Electoral College? Swing State/Battleground State: In Presidential elections, states that do not consistently vote for either the Democratic or Republican Presidential candidate. In the 2012 election, likely swing states are noted in bold italic with an *. Florida Votes in 2000: • Gore: 2,912,253 votes; Bush: 2,912,790 votes • Bush wins Florida’s 27 electoral votes (and the Presidency), even though Gore had more than 540,000 popular votes. -

White Backlash in a Brown Country

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 50 Number 1 Fall 2015 pp.89-132 Fall 2015 White Backlash in a Brown Country Terry Smith DePaul University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Terry Smith, White Backlash in a Brown Country, 50 Val. U. L. Rev. 89 (2015). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol50/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Smith: White Backlash in a Brown Country Lecture WHITE BACKLASH IN A BROWN COUNTRY Terry Smith I would like to honestly say to you that the white backlash is merely a new name for an old phenomenon . It may well be that shouts of Black Power and riots in Watts and the Harlems and the other areas, are the consequences of the white backlash rather than the cause of them.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 90 II. PRIVILEGE AS ADDICTION, DEMOGRAPHY AS THREAT: EXPLAINING THE ETIOLOGY OF BACKLASH ........................................................................... 94 III. BACKLASH AND THE REVIVIFICATION OF CLASSICAL RACISM ............... 105 A. A Creeping “New White Nationalism?” .................................................. 106 B. The Othering of a President ...................................................................... 113 IV. WHITE BACKLASH AT THE BALLOT BOX: THE FIRE NEXT TIME ............ 117 A. From Inevitability to Backlash: Fallacies, Fears, and Suppression .......... 118 1. (Mis)Counting on Latinos .................................................................... -

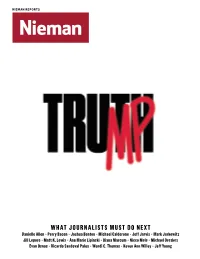

WHAT JOURNALISTS MUST DO NEXT Danielle Allen • Perry Bacon • Joshua Benton • Michael Calderone • Jeff Jarvis • Mark Jurkowitz Jill Lepore • Matt K

NIEMAN REPORTS WHAT JOURNALISTS MUST DO NEXT Danielle Allen • Perry Bacon • Joshua Benton • Michael Calderone • Jeff Jarvis • Mark Jurkowitz Jill Lepore • Matt K. Lewis • Ann Marie Lipinski • Diana Marcum • Nicco Mele • Michael Oreskes Evan Osnos • Ricardo Sandoval Palos • Wendi C. Thomas • Keven Ann Willey • Jeff Young Contributors The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University www.niemanreports.org Keith O’Brien (page 6) is a former reporter for The Boston Globe, a correspondent for National Public Radio, and author. He has written for The New York Times Magazine, Politico, and Slate, among other publications. Gabe Bullard (page 12) is the senior publisher producer, digital and strategy, for 1A, a new Ann Marie Lipinski public radio show launching in 2017 on editor stations across the country. A 2015 Nieman James Geary Fellow, he is the former deputy director of senior editor digital news at National Geographic. Jan Gardner editorial assistant Carla Power (page 20) is the author of the Eryn M. Carlson 2016 Pulitzer finalist “If the Oceans Were design Ink: An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to Pentagram the Heart of the Quran,” about her studies Donald Trump’s rise to the presidency is being viewed by journalists and historians as an important time to reflect on the best way to move forward editorial offices with a traditional Islamic scholar. She is a One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, former correspondent for Newsweek. MA 02138-2098, 617-496-6308, Contents Fall 2016 / Vol. 70 / No. 4 [email protected] Naomi Darom (page 26), a 2016 Nieman Copyright 2016 by the President and Features Departments Fellows of Harvard College.