Michael C. Coleman University of Jyvaskyla. Finland William Mandel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXT1ENSIONS of RE.MARKS THOUGHTFULNESS ACROSS PARTY This Doesn't Mean the End of the Two

September 11, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 25183 EXT1ENSIONS OF RE.MARKS THOUGHTFULNESS ACROSS PARTY This doesn't mean the end of the two-. firmly concludes that employer has not LINES party system in America, of course, but it was satisfied its burden of proof," established a nice thing for Mr. and Mrs. Nixon, Repub in licans, to do for Mr. and Mrs. Johnson, by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Democrats. Weeks v. Southern Bell Telephone and HON. CHARLOTTE T. REID Telegraph Co., 408 F. 2d 228 0969): OF ILLINOIS Good manners and thoughtfulness indeed can cross party lines. namely, that the employer must have "a IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES factual basis for believing, that all or Thursday, September 11, 1969 substantially all women would be unable to perform safely and efficiently the Mrs. REID of Illinois. Mr. Speaker, A SIGNIFICANT COURT DECISION duties of the job involved." recently the Nation witnessed a signifi AGAINST SEX DISCRIMINATION Most significant is Judge Johnson's ob cant display of national unity, tran IN EMPLOYMENT servation that the employer oughrt "to scending partisan political lines, in the determine on an individual basis gracious meeting between President and whether a person is qualified for the posi Mrs. Nixon and former President and HON. MARTHA W. GRIFFITHS tion," rather than using a "class distinc Mrs. Johnson. OF MICHIGAN tion" which "deprives some women of Editorials pointing out the merits of IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES what they regard as a lucrative and this symbolic joining of hands appeared Thursday, September 11, 1969 otherwise desirable position." in the Christian Science Monitor on Certainly, I commend Judge Johnson August 25 and the Atlanta Constitution Mrs. -

1968 Sep 4 to 17 Numbering Goes Awry

........ '-. A vacation gone to South Bend with Tom, lying in a strange attic without an alarm clock to tell me the time to get up and go to the station. The cat wakes up first and pushes her nose in my face letting me know she's hungry. Yowling downstairs to flowers out the ..window', in the neighbor's yard. Long haired people moving into quiet streets and antique houses. The cops just chew gum and a non-frenetic, middle-aged, female real estate agent is anxious to make an artists' colony out of South Bend--a new La Conner. It looks like a good place to live. Tom ( last night) volunteers to be KRAB's Publicity Director creating minor explosions of confusion and inconsistency to lighten the load of those poor people who have to get out a dull newspaper everyday. And ~ plans for benefits, experimental environments; Snow White & the Seven Dwarfs with an 'appropriate; cast. The , station. This first night away was a series of im pulses to turn on the radio that went away with sleep and came back in the morning. Hitchhiking on the road to Portland. Overcast skies, walking by the ocean, a pack on my back; no one stopping, SUSP1Cl0US looks from people in campers and Pontiacs. They're gone without anger, slamming by with allY right to be alone, not knowing me, long hair in the wind. Later at an intersection, after one ride, a light metallic-blue new Chrysler with a Texas license plate slows for me. A well dressed softly fat lawyer in the Northwest looking for a resort or hotel to buy and move away from Texas with. -

Other Minds Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8wq0984 Online items available Guide to the Other Minds Records Alix Norton, Jay Arms, Madison Heying, Jon Myers, and Kate Dundon University of California, Santa Cruz 2018 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Guide to the Other Minds Records MS.414 1 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Other Minds records Creator: Other Minds (Organization) Identifier/Call Number: MS.414 Physical Description: 399.75 Linear Feet (404 boxes, 15 framed and oversized items) Physical Description: 0.17 GB (3,565 digital files, approximately 550 unprocessed CDs, and approximately 10 unprocessed DVDs) Date (inclusive): 1918-2018 Date (bulk): 1981-2015 Language of Material: English https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f1zk5ftt Access Collection is open for research. Audiovisual media is unavailable until reformatted. Digital files are available in the UCSC Special Collections and Archives reading room. Some files may require reformatting before they can be accessed. Technical limitations may hinder the Library's ability to provide access to some digital files. Access to digital files on original carriers is prohibited; users must request to view access copies. Contact Special Collections and Archives in advance to request access to audiovisual media and digital files. Publication Rights Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. -

" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> Smash Apartheid-For Workers Revolution I" =~ ~ !:F Jj;, ..!!!L'" Ii ..Ill Iii ~ • I JUNE 20-The Cold-Blooded Slaughter ',>

..:.. -~ ~ #. c.l ~ Of> "" -~ ~ ~4- WfJRNERS ,,IN'II,IR' 25¢ iJj ':~))c.523 25 June 1976 ;" No. 115 lit I •ill Smash Apartheid-For Workers Revolution I" =~ ~ !:f jj;, ..!!!l'" Ii ..ill iii ~ • I JUNE 20-The cold-blooded slaughter ',>-. of school children in Soweto has caused '%~ the smoldering discontent of South i Africa's urban black masses to flare into open rebellion. For a few days this week I the "African townships" on the Witwa tersrand, the mining and industrial I heartland surrounding Johannesburg, I saw thousands-strong crowds of work ers and youth hurl themselves against I the symbols of oppression with torches, I knives, stones and bare hands. This plebeian revolt illuminates the seething unrest of the subjugated non-white = population of the apartheid police state. Only hours after issuing orders to "maintain law and order at all costs," South African prime minister Balthazar " Vorster embarked for West Germany where he will confer with U.S. secretary I of state Henry Kissinger. Their hands stained with the blood of Indochinese, 4 black Americans. Angolans and South t'- Africans, these tWO statesmen of irr:peri - uPI d a\ist butchery and white supremacist South African students protesting minority rule were brutally attacked by police in Soweto iast week. ~ barbarism will no doubt find a great - deal in common. Both have an interest ........ starvation in Chile, has joined Reagan The police aimed their weapons and - in ballyhooing the sham "indepen in criticizing Kissinger's recent trip fired without warning. One teenage dence" of the Transkei, so-called "tribal through black Africa and has even student fell dead with a slug in his chest. -

Guide to the American Women Making History and Culture: 1963-1982 Collection PRA.RS.001

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c83f4v6g Online items available Guide to the American Women Making History and Culture: 1963-1982 Collection PRA.RS.001 Jolene M. Beiser, MA, MLIS, Archivist Pacifica Radio Archives This finding aid was produced thanks to a matching grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission at the National Archives and Records Administration. Pacifica Radio Archives April 12, 2016 3729 Cahuenga Blvd., West North Hollywood, CA 91604 jolene at pacificaradioarchives dot org URL: http://pacificaradioarchives.org/ Guide to the American Women Making PRA.RS.001 1 History and Culture: 1963-1982 Collection PRA.RS.001 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Pacifica Radio Archives Title: Guide to the American Women Making History and Culture: 1963-1982 Collection creator: KPFA (Radio station : Berkeley, Calif.) creator: KPFK (Radio station : Los Angeles, Calif.) creator: KPFT-FM (Radio station : Houston, Tex.) creator: Pacifica Radio Archives creator: WBAI Radio (New York, N.Y.) creator: WPFW (Radio station : Washington, D.C.) Identifier/Call Number: PRA.RS.001 Physical Description: 2024 Reels Physical Description: 2.39 Terabytes Physical Description: 156 Linear Feet Date (bulk): 1963-1982 Date (inclusive): 1944-1994 Abstract: The American Women Making History and Culture: 1963-1982 collection includes 2,024 reel-to-reel tapes and 2,024 WAV files preserved as part of the Pacifica Radio Archives’ 2013-2016 “American Women Making History and Culture: 1963-1982” (“American Women”) preservation project. The recordings were selected as an “artificial collection” to document the Women’s movement and second-wave feminism as it was broadcast on the Pacifica network. -

Extensions of Re.Marks

August 3, 1976 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 25373 the purpose of continuing such research. H.R. 14749. July 20, 1976. Judiciary. Re Mammal Protection Act of 1972 to prohibit Authorizes, under the Public Health Serv quires that persons convicted of specified the issuance of permits thereunder which ice Act, the appropriation of specified sums terrorist activities receive a sentence addi authorize the taking of marine mammals in for the purposes of making gra.nts to centers tional to that provided for the offense com connection with commercial fishing. for research and training in diabetic re mitted. Directs that the death sentence be Amends such Act to grant the Secretary lated disorders. imposed if the death of any person occurs of the Interior exclusive jurisdiction over H.R. 14744. July 20, 1976. Interstate and during the commission or attempted com such Act. Foreign Commerce. Amends the Public mission of such an offense. Permits reduction H.R. 14756. July 20, 1976. Banking, Cur Health Service Act to direct the Secretary of of the death sentence to an additional term rency and Housing. Establishes a National Health, Education, and Welfare to indemnify of imprisonment if the required sentencing Commission on Neighborhoods to consist of · physicians, health care personnel, and health hearing results in a finding that specified Members of Congress and Presidential ap facilities providing nonprofit professional mitigating factors exist. pointees. States the duties of such Commis services in connection with the national in H.R. 14750. July 20, 1976. International sion, including studying the factors neces fluenza immunization program against civil Relations; Interstate and Foreign Commerce. -

People's World Photograph Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pz5fz6 No online items Finding Aid to the People's World Photograph Collection Finding aid prepared by Labor Archives staff. Labor Archives and Research Center 2012, Revised 2017 San Francisco State University 1630 Holloway Ave San Francisco 94132-1722 [email protected] URL: http://www.library.sfsu.edu/larc Finding Aid to the People's World larc.pho.00091986/073, 1990/013, 1992/003, 1992/049, 1 Photograph Collection 1994/037, 2011/015 Title: People's World Photograph Collection Date (inclusive): 1856-1992 Date (bulk): 1930-1990 Creator: People's World. (San Francisco, Calif.). Extent: 22 cubic ft. (45 boxes) Call number: larc.pho.0009 Accession numbers: 1986/073, 1990/013, 1992/003, 1992/049, 1994/037, 2011/015 Contributing Institution: Labor Archives and Research Center J. Paul Leonard Library, Room 460 San Francisco State University 1630 Holloway Ave San Francisco, CA 94132-1722 (415) 405-5571 [email protected] Abstract: The People's World Photograph Collection consists of approximately 6,000 photographs used in People's World, a grassroots publication affiliated with the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA). The photographs, along with a small selection of cartoons and artwork, highlight social and political issues and events of the 20th century, with the views of the newspaper aligning with the CPUSA's policies on topics such as civil rights, labor, immigration, the peace movement, poverty, and unemployment. The photographs, the bulk of which span the years 1930 to 1990, comprise predominantly black and white prints gathered from a variety of sources including government agencies, photographic studios, individual photographers, stock image companies, and news agencies, while many of the cartoons and artwork were created by People's World editor and artist Pele deLappe. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS April, 7, 1970 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

10658 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS April, 7, 1970 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CLAUDE BERNARD SCIENCE JOUR United States will accept for publication any for understanding. I am sick of the total ir NALISM AWARDS manuscript containing data derived from rationality of the campus "rebel," whose animal experiments if the editors have reason bearded visage, dirty hair, body odor and to believe, or even suspect, that the animals "tactics" are childish but brutal, naive but: HON. PAUL J. FANNIN in question were mishandled in any way. dangerous, and the essence of arrogant tyr OF ARIZONA Further, Morse, had he Wished to do so, anny-the tyranny of spoiled brats. could have discovered that positively no fed IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES eral research grants are awarded to any scien SOFT TOUCH Tuesday, April 7, 1970 tist or institution Without an on-site inspec I am terribly disturbed that I may be in tion of laboratory and animal facilities and cubating more of the same. Our household Mr. FANNIN. Mr. President, the Na methods, plus a careful screening of the is permissive, our approach to discipline is tional Society for Medical Research has scientists themselves. an apology and a retreat from standards honored an Arizona writer for "respon Federal laws governing animal research are usually accompanied by a gift in cash or sible science reporting which has made extremely rigid and detailed, and are strictly kind. a significant contribution to public un enforced. It's time to call a halt; time to live in an Another indication of the author's lack of adult world where we belong and time to derstanding of basic research in the life scientific knowledge is shown in his sugges put these people in their places. -

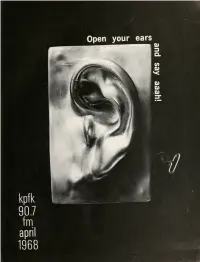

KPFK Folio Is Published Month- Ly by KPFK-Ftvl, a Non-Protit

Open your ears — IN MEMORIAM: SASHA SHOR (October 2, 1890 — February 17, 1968) In search for the words which would best express a fitting tribute to the memory of Sasha Shor I concluded that Sasha's own words about himself would serve better than anything I could say. After listening to 32 sessions on Cuisine Bourgeoise and attending some of his classes, I would add that only Sasha could introduce a recipe Coq au Vin or Mousse Chocolat and proceed to reveal the man and his philosophy for living. Among his epigrammatic instructions one heard, "You dont cook to impress your friends, you cook to please them." He believed that "in order to cook well, one must have plenty of love.* And that "a little more or less* was no crime. His concept of the truth was not an intellectual one, but rather an emotional experience to be shared at the very moment of its happening; so that, to come into contact with Sasha, however briefly, was to find oneself encom- passed by hiscameraderie, goodhumor, concern but without fear, and above all, hope. He took issue with our Declaration of Independence on its "unalienable right . to the pursuit of happiness." He felt that "happiness* is the moment that isi "How can you PURSUE happiness?" he would ask. The word "happy* seemed to be one of the most frequently used in Sasha's vocabulary. Shrimp are cooked just right when they blush pink with happiness. A good wine is one that brings "smiles in the mouth." The taste of one of culinary delights can be "amusing." The only kind of garlic to us is "happy gloves" (cloves). -

Media Moralities, Comedic Inversions, and the First Amendment Anna Lisa

"Pigs Ate My Roses": Media moralities, comedic inversions, and the First Amendment Anna Lisa Candido Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University Montreal, Quebec March 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies. © Anna Candido, 2018 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the politics of morality that structured the moral development of mass and niche media forms in America between the 1930s and late 1970s. In order to understand how media became entangled in moral struggles, this work begins by tracing the rise of moral regulation in film and broadcasting in the 1930s and 40s, and the ways that live performance, narrowcast recording, and listener-sponsored radio enabled forms of expression around gender, sexuality, race, crime, and vice that had been unconstitutionally prohibited in mass media. To do this, this dissertation examines a number of critical moments at which community and religious groups charged performers or media players with the loosely-defined concepts of “obscenity” or “indecency” as a way of establishing moral boundaries in mediated culture. By charging Mae West, Lenny Bruce, George Carlin, and listener-sponsored radio stations with obscenity or indecency, groups like the Legion of Decency and Morality in Media (in concert with other state and industry players) exerted significant control over forms of expression that may have otherwise circulated freely under the protection of the First Amendment. Although these groups succeeded in producing discursive and representational limits in film and broadcasting between the 1930s and 1970s, the semi-hiddenness of live performance spaces, niche recordings, and listener-sponsored radio partially or temporarily sheltered controversial performers and allowed like-minded people to convene over unorthodox expressions that more adequately reflected the depth and complexity of their affective states, experiences, or social positions. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS April 6, 1970 Black

10432 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS April 6, 1970 Black. and nothing comparable to the any been presented subsequent to the before the unfinished business is laid be brilliant public service of Senator Byrnes hearings. fore the Senate. that preceded his brief service on the I hope I am mistaken in my assess Supreme Court. ment of Judge Carswell. The demands Comparisons are also inevitable with upon the Court during the remainder of ADJOURNMENT TO 10 A.M. two southerners who have been denied this century will be great. It is quite pos TOMORROW a place on the Court in this century sible that this nominee, if confirmed, Mr. BYRD of West Virginia. Mr. Presi Judge John J. Parker of North Carolina might well serve for most of the balance dent, if there be no further business to and Judge Clement Haynsworth of South of this century. This has been a difficult come before the Senate, I move in ac Carolina. decision and I have come to have regrets cordance with the previous order, that Dean Pollak, of the Yale Law School. about a system that has subjected three the Senate stand in adjournment until when pressed for such a comparison of of the last four nominees to the type of 10 o'clock tomorrow morning. the nominee with Judge Parker said as national debate that has resulted. Never The motion was agreed to; and Cat 2 follows: theless, for me there remain unanswered o'clock and 55 minutes p.m.> the Senate Senator, Judge Parker has been very much questions about the nominee. -

American Intellectuals in the American-Soviet Friendship Movement

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Alone Together: American Intellectuals in the American-Soviet Friendship Movement A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by David Byron Wagner June 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Brian D. Lloyd, Chairperson Dr. Molly McGarry Dr. Kiril Tomoff Copyright by David Byron Wagner 2016 The Dissertation of David Byron Wagner is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Above all, I am indebted to Brian Lloyd, my dissertation advisor, who was so important in helping me to clarify my intentions and arguments in this work. Brian has been an inspired editor, collaborator, and critic. I am enormously grateful and hope he is pleased with the result. I also appreciate the hard work and insightful suggestions of my additional readers Molly McGarry and Kiril Tomoff. Thanks also to Catherine Gudis and John Ganim, who served on my PhD oral exam committee. You are all fantastic. Most of the research for this project was conducted at the Tamiment Library at New York University, which has my thanks for providing access to several collections necessary for this project. I did further research at San Diego State University, the Motion Picture Association of America’s Mary Pickford Center, and Columbia University. I am appreciative of all of the help offered me by archivists in all of these institutions. Special thanks goes to Tamiment archivist Bonnie Gordon, who pointed me toward Morford’s biographical manuscripts in the Abbott Simon Papers, which more or less tied all of the rest of the evidence together.