American Intellectuals in the American-Soviet Friendship Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Processed by Dale Reed. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Dale Reed Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from Microsoft Word and MARC record by Supriya Wronkiewicz. © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Albert Glotzer papers Dates: 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Collection Size: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes (27.7 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. -

The Freeman April 1953

APRIL 20, 1953 Russians Are People Eugene Lyons Decline of the Rule of Law F. A. Hayek The Battle Against Print Flora Rheta Schreiber Red China's Secret Weapon Victor Lasky Santayana: Alien in the World Max Eastman The Reading Company at its huge coal terminal near Perth Amboy handles as much as 4,000,000 tons annually. Most of this coal is distributed to docks in New York City and Brooklyn in 10,000-ton barges. Three new tugs powered with Fairbanks-Morse Diesels and equipped throughout with F-M Generators, Pumps and Motors are setting new records for speed and economy in this important task. Fairbanks, Morse & Co., Chicago 5, Illinois FAIRBANKS·MORSE a name worth remembering when you want the best DIESEL AND DUAL FUEL ENGINES • DIESEL LOCOMOTIVES • RAIL CARS • ELECTRICAL MACHINERY PUMPS • SCALES • HOME WATER SERVICE EQUIPMENT • FARM MACHINERY • MAGNETOS THE A Fortnightly Our Contributors For VICTOR LASKY, well-known journalist and spe cialist on Communism, won national renown in Individualists 1950 as co-author of the best-selling Seeds of reeman Treason. He i's editor of Spadea Syndicates. Editor HENRY HAZLITT EUGENE LYONS is particularly equipped to know Managing Editor FLORENCE NORTON and understand the Russian people, being him self a native of Russia and having spent many years as a correspondent in Moscow. Author of a number of books about the Soviet Union, including a biography of Stalin, he is now Contents VOL. 3, NO. 15 APRIL 20, 1953 working on a book tentatively entitled "Our Secret Weapon: the Russian People." . Editorials FLORA RHETA SCHREIBER is exceptionally quali The Fortnight. -

The Arthur Garfield Hays Civil Liberties Program

THE ARTHUR GARFIELD HAYS CIVIL LIBERTIES PROGRAM ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 August 2020 New York University A private university in the public service School of Law Arthur Garfield Hays Civil Liberties Program 40 Washington Square South New York, New York10012-1099 Co-Directors Professor Emerita Sylvia A. Law Tel: (212) 998-6265 Email:[email protected] Professor Helen Hershkoff Tel: (212) 998-6285 Email: [email protected] THE ARTHUR GARFIELD HAYS CIVIL LIBERTIES PROGRAM ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability, but comes through continuous struggle. — Martin Luther King, Jr. This Report summarizes the activities of the Hays Program during AY 2019–2020.The year presented extraordinary challenges, as well as important opportunities. Above all, the Hays Program remained steadfast in its central mission: to mentor a new generation of lawyers dedicated to redressing historic inequalities, to resisting injustice, and to protecting democratic institutions. The heart of the Program remained the Fellows and their engagement with lawyers, advocates, and communities through their term-time internships and seminar discussions aimed at defending civil rights and civil liberties. The academic year began with the Trump administration’s continuing assault on the Constitution, from its treatment of immigrants, to its tacit endorsement of racist violence, fueled by the President’s explicit use of federal judicial appointments to narrow civil rights and civil liberties (at this count, an unprecedented two hundred). By March, a global pandemic had caused the Law School, like the rest of the world, to shutter, with the Hays seminar, along with all courses, taught remotely. -

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St. Petersburg to Chicago Pamphlets Explanatory Power I 6 fDK246.S2 M. Dobrov Chto takoe burzhuaziia? [What is the Bourgeoisie?] Petrograd: Petrogr. Torg. Prom. Soiuz, tip. “Kopeika,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 39 fDK246.S2 S.K. Neslukhovskii Chto takoe sotsializm? [What is Socialism?] Petrograd: K-vo “Svobodnyi put’”, [n.d.] Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 10 fDK246.S2 Aleksandra Kollontai Kto takie sotsial-demokraty i chego oni khotiat’? [Who Are the Social Democrats and What Do They Want?] Petrograd: Izdatel’stvo i sklad “Kniga,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets I 7 fDK246.S2 Vatin (V. A. Bystrianskii) Chto takoe kommuna? (What is a Commune?) Petrograd: Petrogradskogo Soveta Rabochikh i Krasnoarmeiskikh Deputatov, 1918 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 32 fDK246.S2 L. Kin Chto takoe respublika? [What is a Republic?] Petrograd: Revoliutsionnaia biblioteka, 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 31 fDK246.S2 G.K. Kryzhitskii Chto takoe federativnaia respublika? (Rossiiskaia federatsiia) [What is a Federal Republic? (The Russian Federation)] Petrograd: Znamenskaia skoropechatnaia, 1917 1 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E42 fDK246.S2 O.A. Vol’kenshtein (Ol’govich): Federalizm v Rossii [Federalism in Russia] Knigoizdatel’stvo “Luch”, [n.d.] fDK246.S2 E33 I.N. Ignatov Gosudarstvennyi stroi Severo-Amerikanskikh Soedinenykh shtatov: Respublika [The Form of Government of the United States of America: Republic] Moscow: t-vo I. D. Sytina, 1917 fDK246.S2 E34 K. Parchevskii Polozhenie prezidenta v demokraticheskoi respublike [The Position of the President in a Democratic Republic] Petrograd: Rassvet, 1917 fDK246.S2 H35 Prof. V.V. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

Tufts University the American Left And

TUFTS UNIVERSITY THE AMERICAN LEFT AND STALIN'S PURGES, 1936-38: FELLOW-TRAVELLERS AND THEIR ARGUMENTS UNDERGRADUATE HONORS THESIS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY by SUSAN T. CAULFIELD DECEMBER 1979 CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. SHOW TRIALS AND PURGES IN THE SOVIET UNION, 1936-38 7 III. TYPOLOGY OF ARGUMENTS 24 IV. EXPLANATIONS .••.•• 64 V. EPILOGUE: THE NAZI-SOVIET PACT 88 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 95 I. INTRODUCTION In 1936, George Soule, an editor of the New Republic, described in that magazine the feelings of a traveller just returned from the Soviet Union: ••• After a week or so he begins to miss something. He misses the hope, the enthusiasm, the intellectual vigor, the ferment of change. In Russia people have the sense that something new and better is going to happen next week. And it usually does. The feeling is a little like the excitement that accompanied the first few weeks of the New Deal. But the Soviet New Deal has been going on longer, is proyiding more and more tangible results, and retains its vitality ..• For Soule, interest in the "Soviet New Deal" was an expression of dis- content with his own society; while not going so far as to advocate So- viet solutions to American problems, he regarded Soviet progress as proof that there existed solutions to those problems superior to those offered by the New Deal. When he and others on the American Left in the 1930's found the Soviet Union a source of inspiration, praised what they saw there, and spoke at times as if they had found utopia, the phenomenon was not a new one. -

How Early Post Office Policy Shaped Modern First Amendment Doctrine

Hastings Law Journal Volume 58 | Issue 4 Article 1 1-2007 The rT ansformation of Statutes into Constitutional Law: How Early Post Officeolic P y Shaped Modern First Amendment Doctrine Anuj C. Desai Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anuj C. Desai, The Transformation of Statutes into Constitutional Law: How Early Post Officeo P licy Shaped Modern First Amendment Doctrine, 58 Hastings L.J. 671 (2007). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol58/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles The Transformation of Statutes into Constitutional Law: How Early Post Office Policy Shaped Modern First Amendment Doctrine ANUJ C. DESAI* INTRODUCTION One of the great urban legends on the Internet was "Bill 6o2P."' In the late 199OS it spread like wildfire, and it occasionally makes the rounds again like pleas from Nigerian officials seeking help with their Swiss bank accounts or the story of the $250 Neiman Marcus cookie recipe. The bill, supported by (no doubt soon-to-be-defeated) "Congressman Tony Schnell," would have imposed a five cent tax on each e-mail message. One would be hard put to imagine a more nefarious way for * Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School. Many people read all or large parts of this Article and provided helpful suggestions. -

The Politics of Being Mortal

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Gerontology, Family, and Life Course Sociology 1988 The Politics of Being Mortal Alfred G. Killilea University of Rhode Island Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Killilea, Alfred G., "The Politics of Being Mortal" (1988). Gerontology, Family, and Life Course. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_gerontology/3 The POLITICS of BEING MORTAL This page intentionally left blank The POLITICS of BEING MORTAL Alfred G. Killilea THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright O 1988 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0336 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-PublicationData Killilea, Alfred G., 1941- The politics of being mortal / Alfred G. Killilea. p. cm. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-813 1-5287-5 1. Death-Social aspects-United States. 2. Death-Political aspects-United States. 3. Social values. I. Title. HQ1073.5.U6K55 1988 306.9-dc19 88-9422 This book is printed on acid-free To my daughter, MARI November 2 1, 1970 - October 26,1987 You taught me pure joy in play, the diligence behind achievement, and finally the full depth of the human condition. -

Mediating Civil Liberties: Liberal and Civil Libertarian Reactions to Father Coughlin

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2008 Mediating Civil Liberties: Liberal and Civil Libertarian Reactions to Father Coughlin Margaret E. Crilly University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Crilly, Margaret E., "Mediating Civil Liberties: Liberal and Civil Libertarian Reactions to Father Coughlin" (2008). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1166 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Margaret Crilly Mediating Civil Liberties: Liberal and Civil Libertarian Reactions to Father Coughlin Marta Crilly By August 15, 1939, Magistrate Michael A. Ford had had it. Sitting at his bench in the Tombs Court of New York City, faced with a sobbing peddler of Social Justice magazine, he dressed her down with scathing language before revealing her sentence. "I think you are one of the most contemptible individuals ever brought into my court," he stated. "There is no place in this free country for any person who entertains the narrow, bigoted, intolerant ideas you have in your head. You remind me of a witch burner. You belong to the Middle Ages. You don't belong to this modem civilized day of ours .. -

House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)

Cold War PS MB 10/27/03 8:28 PM Page 146 House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) Excerpt from “One Hundred Things You Should Know About Communism in the U.S.A.” Reprinted from Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts From Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968, published in 1971 “[Question:] Why ne Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- shouldn’t I turn “O nism in the U.S.A.” was the first in a series of pam- Communist? [Answer:] phlets put out by the House Un-American Activities Commit- You know what the United tee (HUAC) to educate the American public about communism in the United States. In May 1938, U.S. represen- States is like today. If you tative Martin Dies (1900–1972) of Texas managed to get his fa- want it exactly the vorite House committee, HUAC, funded. It had been inactive opposite, you should turn since 1930. The HUAC was charged with investigation of sub- Communist. But before versive activities that posed a threat to the U.S. government. you do, remember you will lose your independence, With the HUAC revived, Dies claimed to have gath- ered knowledge that communists were in labor unions, gov- your property, and your ernment agencies, and African American groups. Without freedom of mind. You will ever knowing why they were charged, many individuals lost gain only a risky their jobs. In 1940, Congress passed the Alien Registration membership in a Act, known as the Smith Act. The act made it illegal for an conspiracy which is individual to be a member of any organization that support- ruthless, godless, and ed a violent overthrow of the U.S. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

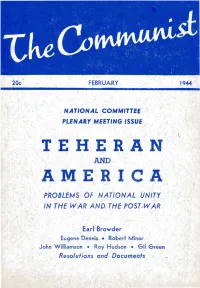

Earl Browder F I Eugene Dennis • Robert Minor John Willia-Mson • Roy · Hudson • Gil G R,Een Resolutions And.· Documents I • I R

I . - > 20c FEBRUARY 1944 ' .. NATIONAL COMMITTE~ I PLENARY MEETING ISSUE ,. - • I ' ' ' AND PROBLEMS OF NATIONAL UNIT~ ' ·- ' . IN THE WAR AND THE POST-~AR I' • Earl Browder f I Eugene Dennis • Robert Minor John Willia-mson • Roy · Hudson • Gil G r,een Resolutions and.· Documents I • I r / I ' '. ' \' I , ... I f" V. I. L~NIN: A POLITICAL, BIOGRAP,HY 1' ' 'Pre pared by' the Mc);;·Engels.Le nin 'Institute, t his vo l ' ume provides b new ana authoritative 'study of t he life • and activities of the {9under and leader of the Soviet . Union up to thf;l time of Le11i n's death. P r.~ce $ 1.90 ~· .. • , f T'f'E RED ARMY By .Prof. I. Mi111. , The history and orgon lfqtion of the ~ed Army ·.and a iJt\fO redord1of its ~<;hievem e nfs fr9 m its foundation fhe epic V1cfory ,tal Stalingrad. Pl'i ce $1.25 I SOVIET ECONOMY AND !HE WAR By Dobb ,. ' Maur fc~ • ---1· •' A fadyal record of economic developm~nts during the last .few years with sp6""cial re?erence ..to itheir bearing '/' / on th~ war potentiaJ··and· the needs of the w~r. Price ~.25 ,- ' . r . ~ / .}·1 ' SOVIET PLANNING A~ D LABOR IN PEACE AND WAR By Maurice Oobb ' ' 1 - I A sh~y of economic pl~nning, the fln~ncia l . system, ' ' ' . work , wages, the econorpic effects 6f the war, end other ' '~>pecial aspects of the So'liet economic system prior to .( and during the w ~ r , · Price ·$.35 - I ' '-' I I • .. TH E WAR OF NATIONAL Llij.E R ATIO~ (in two· parts) , By Joseph ·stalin '· A collecfion of the wa~fime addr~sses of the Soviet - ; Premier and M<~rshal of the ·Rep Army, covering two I years 'o.f -the war ~gains+ the 'Axis.