Code Switching As a Poetic Device: Examples from Rai Lyrics Q

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Mort Du Raï ? Sans Blague ? Il Est Trop Heureux D'épouser Les Formes

La mort du Raï ? Sans blague ? Il est trop heureux d'épouser les formes nouvelles, comme il l'a fait avec la funk, le chaâbi égyptien ou la musique de Bollywood tout en plongeant ses racines si profond dans la croûte terrestre oranaise, fécondée par les bédouins qui trafiquent du son de l'Ethiopie au Mali, par les réfugiés d'Al-Andalus dont les écoles de Nouba rayonnent toujours, la poésie des chioukh, le phaser des gasbas. Sofiane Saidi est un rescapé de la vague World Music des années 90. Ou plutôt un vainqueur comme on dit pour les navigateurs, un gars qui malgré les tempêtes et les escroqueries de l'armateur qui a menti sur la qualité du bois utilisé pour la coque du bateau, continue la traversée et arrive à bon port. Il vient du fief des frères Zergui qu'il trace de mariage en mariage, le nez au vent de Sidi Bel Abbes pour savoir où ça joue, en se rapprochant chaque soir du podium pour écouter mieux et finalement prendre le micro. A 15 ans, il chante dans les clubs mythiques d'Oran : les Andalouses, le Dauphin, où se produisent les stars Benchenet, Hasni, Fethi, Marsaoui. Fuyant le FIS et la terreur en Algérie, Sofiane a 17 ans quand il arrive à Paris. Après 2 ans de galère, sans chanter, sans musique, il retrouve le milieu raï des cabarets. C'est le même qu'en Algérie : prostituées, musiciens, dealers, fêtards, travestis, escrocs, en plus dangereux, en moins naïf. C'est aussi la diaspora intellectuelle et artistique qui se retrouve en France pendant qu'en Algérie, on tue Cheb Hasni, Rachid Baba Ahmed, Cheikh Zouaoui. -

1 Nasser Al-Taee University of Tennessee, Knoxvi

Echo: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) Nasser Al-Taee University of Tennessee, Knoxville “In rai, there are always enemies, always problems.” Dijillai, an Algerian fan (Shade-Poulsen 124) 1. It is no coincidence that rai surged onto the Algerian popular music landscape during the 1980s, a time in which Islamic reformists brought about new challenges to the political, cultural, and artistic scenes in the developing country. [Listen to an example of rai.] Caught between tradition and modernization, and reacting to the failure of socialism and its inability to appeal to the majority of the Algerian masses, the country sank into a brutal civil war between the military- backed regime and Islamic conservatives demanding a fair democratic election. Algerian rai artists responded by expressing disenchantment with their country’s situation through a modernized genre largely based on its traditional, folk-based, sacred ancestor. In Arabic rai means “opinion,” a word reflecting the desire for freedom of speech and expression, values that have been subjected to extreme censorship by non-democratic Arab governments. Currently, rai is associated with an emerging youth culture and the new connotations ascribed to the genre reflect 1 Echo: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) tenets of liberalism that depart from the past. In its newly adopted form, rai represents an alternative mode of protest and liberation. 2. When new rai began to achieve popularity in Algeria and Europe in the late 70s and early 80s, rai artists and the conservative factions were at odds with each other because of their conflicting ideological positions. -

Oran Is the New Black Algeria’S Second City Is Unique for Its Sights, Coastline and Fusion Flavours with Berber, Arab and European Influences

ART & LIFE 3 TRAVEL ALGERIA The building of the now extinct Disco Maghreb label is a shrine for Raï fans Oran is the new black Algeria’s second city is unique for its sights, coastline and fusion flavours with Berber, Arab and European influences. Pack your swimmers and comfortable shoes and make the most of 48 hours in this West Coast Mediterranean hub, taking in the shops, the sounds and the sea PHOTOGRAPHER tart your day with a freshly cinema and plenty of florists. Pick up At seafood restaurant Le Corsaire, squeezed orange juice, a good some Algerian pastries from L’Algéroise dive into the catch of the day or their S café au lait (kahwa halib) and – perhaps some griwech, a sweet local famous paella, a reminder of the Spanish a croissant, either on the terrace of the pastry with honey, the dry biscuit torno influences on the region. End the day Four Points hotel – while gazing out or ghoriba shortbread. Raï fans will def- by climbing up to Santa Cruz, to the across the magnificent sea and inhaling initely want to pay homage at the Disco chapel built in the 16th-century during the fresh Mediterranean air – or, if you Maghreb building; the legendary label the Spanish colonisation. Here you can prefer it strong and to the point, and and record store has now closed down- marvel at the town and sea from above. dirt cheap, at the counter of any café. but you can grab some Cheb Khaled, Next day, with your new playlist on First stop is the Musée National Cheb Hasni and Raina Raï from stores the go, drive along the coastline past Ahmed Zabana, named after the in- in Les Arcades. -

Various La Nuit Du Raï Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various La Nuit Du Raï mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: La Nuit Du Raï Country: France Released: 2011 Style: Raï MP3 version RAR size: 1613 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1496 mb WMA version RAR size: 1741 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 364 Other Formats: MP3 AC3 MPC MOD AHX AIFF MP4 Tracklist Hide Credits CD1 Raï RnB 1 –El Matador Featuring Amar* Allez Allez 3:31 2 –Cheb Amar Sakina 3:24 3 –Dj Idsa Featuring Big Ali & Cheb Akil Hit The Raï Floor 3:44 4 –Dj Idsa Featuring Jacky Brown* & Akil* Chicoter 4:02 5 –Swen Featuring Najim Emmène Moi 3:44 6 –Shyneze* Featuring Mohamed Lamine All Raï On Me 3:25 –Elephant Man Featuring Mokobé Du 113* & 7 Bullit 3:22 Sheryne 8 –L'Algérino Marseille By Night 3:41 9 –L'Algérino Featuring Reda Taliani M'Zia 3:56 10 –Reyno Featuring Nabil Hommage 5:19 11 –Hass'n Racks* Wati By Raï 2:50 12 –Hanini Featuring Zahouania* Salaman 5:21 –DJ Mams* Featuring Doukali* Featuring 13 Hella Décalé (Version Radio Edit) 3:16 Jahman On Va Danser 14 –Cheb Fouzi Featuring Alibi Montana 2:56 Remix – Soley Danceflor 15 –Cheb Rayan El Babour Kalae Mel Port 3:46 16 –Redouane Bily El Achra 4:04 17 –Fouaz la Classe Poupouna 4:38 18 –Cheb Didine C Le Mouve One Two Three 4:03 19 –Youness Dépassite Les Limites 3:40 20 –Cheb Hassen Featuring Singuila Perle Rare 3:26 CD2 Cœur Du Raï 1 –Cheba Zahouania* & Cheb Sahraoui Rouhou Liha 2 –Cheba Zahouania* Achkha Maladie 3 –Bilal* Saragossa 4 –Abdou* Balak Balak 5 –Abdou* Apple Masqué 6 –Bilal* Tequiero 7 –Bilal* Un Milliard 8 –Khaled Didi 9 –Sahraoui* & Fadela* -

Les Múltiples Identitats Del Raï

LES MÚLTIPLES IDENTITATS DEL RAÏ Josep Vicent Frechina Dels bordells i cafés d’Orà als su- La caracterització del raï no és nories: jueus, espanyols, etc.; des- burbis de París, de la veu subversi- gens fàcil perquè, d’una banda, és prés, l’enorme impacte de la seua 23 va de les cheikhas 1 a les vendes mi- un fenomen social que transcen- comercialització a través dels mer- lionàries dels cantants beurs , de la deix llargament el fet estrictament cats de cintes de casset; més tard, el parada itinerant de cintes de casset musical –Schade-Poulsen (1999:5) contacte entre els immigrants als macrofestivals de les «músiques en dirà un «fet social total»–; i, algerians a París i la cultura occi- Caramella ètniques», el raï ha fet un llarg d’una altra, perquè es tracta, com dental; i, finalment, la tremenda viatge en molt poc temps i, pel ja hem subratllar, d’un estil dotat intervenció de la indústria de la 119 camí, ha anat canviant parcialment d’una gran heterogeneïtat on con- world music per conferir a l’estil un la seua fesomia i el seu significat vergeixen trets musicals de molt discurs occidental, és a dir, per fins arribar al complex, heterogeni diversa procedència: ritmes magri- configurar i modelar, en base a un i ambivalent gènere musical que bins, instruments occidentals, ele- imaginari àrab ben bé de disseny, coneixem avui. Un gènere que, ments de música disco, melodies un nou estil musical susceptible de com tan certerament va assenyalar aràbiques, etc. Això es deu, en bo- competir en el mercat de consum l’arabista Gabriele Marranci na mesura, a la seua naturalesa globalitzat amb uns trets que (2003:101), ostenta a més una al·luvial i a les successives dinà- exhibesquen una cert exotisme VEU AMB ALTRA duplicitat de rols contradictòria miques de transculturació i mer- però que no espanten l’oient amb perquè si, d’una banda, és un cantilització a què ha estat sotmés: la seua crua autenticitat. -

The Lives, Deaths and Legacies of Cheb Hasni and Lounès Matoub

“In Our Culture, Poets Have More Power than Politicians”: The Lives, Deaths and Legacies of Cheb Hasni and Lounès Matoub Stephen Wilford City University London [email protected] Abstract This article examines the lives, deaths and legacies of two of the most popular Algerian musicians of the 1990s: “Cheb” Hasni Chakroun and Lounès Matoub. Both were killed at the height of their fame, as a result of the violence produced by the socio-political unrest and civil war in their country. Here, the ways in which these musicians engaged with political discourses are addressed, as well as the controversies that surrounded their subsequent killings. Furthermore, there is a consideration of their ensuing mythologization and place within collective memories of 1990s Algeria, as respected popular musicians, as cultural martyrs and as victims of circumstance. Finally, an assessment is made of their legacies within enduring discourses of political conspiracy, showing how the suspicions of Algerians with regards to their killings enable engagement with contemporary Algerian politics. KEYWORDS: Algeria, Kabylia, Cheb Hasni, Lounès Matoub, memory, conspiracy theories Introduction On 22 June 1961, at the height of the Algerian war of independence, the revered singer “cheikh” Raymond Leiris was shot and killed in the market of Constantine, a city in the east of Algeria. Whilst his killers were never brought to justice, his death illustrated both the violence of this period of Algerian history and the IASPM@Journal vol.5 no.2 (2015) Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music ISSN 2079-3871 | DOI 10.5429/2079-3871(2015)v5i2.4en | www.iaspmjournal.net 42 Stephen Wilford dangers faced by the country’s well-known musicians. -

Rhythms and Rhymes of Life: Music and Identification Processes of Dutch-Moroccan Youth Gazzah, Miriam

www.ssoar.info Rhythms and rhymes of life: music and identification processes of Dutch-Moroccan youth Gazzah, Miriam Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / phd thesis Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Gazzah, M. (2008). Rhythms and rhymes of life: music and identification processes of Dutch-Moroccan youth. (ISIM Dissertations). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-271792 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de RHYTHMSRHYMES AND RHYTHMS AND RHYMES OF LIFE Rhythms and Rhymes of Life: Music and Identification Processes of Dutch- Moroccan Youth is a comprehensive anthropological study of the social significance of music among Dutch-Moroccan youth. In the Netherlands, a Dutch-Moroccan music scene has emerged, including events and websites. Dutch-Moroccan youth are often pioneers in the Dutch hip- OF hop scene, using music as a tool to identify with or distance themselves from others. They (re)present and position themselves in society through LIFE music and musical activities. The chapters deal with the development of the Dutch-Moroccan music scene, the construction of Dutch-Moroccan identity, the impact of Islam on female artists and the way Dutch- Moroccan rappers react to stereotypes about Moroccans. -

L'aventure Du Raï. Musique Et Société

L'aventure du raï L'aventure du raï Musique et société Éditions du Seuil COLLECTION DIRIGÉE PAR NICOLE VIMARD ISBN 2-02-025587-1 © Éditions du Seuil, janvier 1996 Le Code de la propriété intellectuelle interdit les copies ou reproductions destinées à une utilisation collective. Toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle faite par quelque procédé que ce soit, sans le consentement de l'auteur ou de ses ayants cause, est illi- cite et constitue une contrefaçon sanctionnée par les articles L. 335-2 et suivants du Code de la propriété intellectuelle. À Hasni et Rachid, in memoriam. Remerciements Nous remercions pour leurs témoignages, aides et réflexions : Mmes Djamila Benkirane, Zoubida Hagani, Marie Virolle. MM. Nidam Abdi, Bouziane Ahmed-Khodja, Fethi Baba-Ahmed, Bruno Barré, Bayon, Houari Blaoui, Mohamed Chadly-Bengasmia, Philippe Conrath, Adda Hadj-Brahim, Brahim Hadj-Slimane, Noureddine Gafaïti, Mark Kidel, Michel Lévy, Mohamed Maghni, Martin Meissonnier, Rabah Mézouane, Mekki Nouna, Ahmed Ourak dit Djilali, feu El-Hadj Saïm, Marc Schade-Poulsen, Yves Thibord, feu Ahmed Wahby, et tous les artistes cités dans cet ouvrage. Introduction Le 29 septembre 1994, cheb Hasni, un des chanteurs les plus populaires de la chanson raï est assassiné dans son quartier natal à Oran. Ce meurtre, qui s'ajoute aux milliers d'assassinats d'hommes de culture, de journalistes, d'uni- versitaires et d'autres citoyens, paraphe dans le sang l'his- toire, pourtant suffisamment tumultueuse, d'un genre musical populaire et moderne né dans l'Ouest algérien et qui a souvent occupé les devants de l'actualité sociale et culturelle de l'Algérie durant ces quinze dernières années. -

P01 Mise En Page 1

Découverte de 2 casemates contenant des munitions à Djelfa Page 24 PLAINTE DE LA DIRECTION LE JEUNE N° 5887 - DIMANCHE 24 SEPTEMBRE 2017 AGGRAVÉE PAR LA HAUSSE DE L’ÉDUCATION D’ALGER-EST DES PRIX DES PRODUITS 55 directeurs, censeurs AGRICOLES et surveillants généraux INDEPENDANT L’inflation annuelle de lycée à la barre grimpe à 5,9% Page 5 www.jeune-independant.net [email protected] Page 2 Finance islamique dans nos banques publiques ALTERNATIVE HALAL OU PRODUIT MIRACLE ? Le gouvernement prépare déjà l’introduction, pour la première fois en Algérie, de chèques islamiques dans le Trésor de l’Etat. Les rédacteurs du projet de la loi de finances 2018 l’ont prévu dans un des dispositifs qui sera soumis dans une semaine au conseil du gouvernement pour examen et adoption. Mais sommes-nous bien rodés à cette finance ? Avons-nous les compétences pour nous lancer dans ce modèle ? La Banque centrale pourra-t-elle assurer les contrôles de conformité et mettre les garde-fous pour protéger les citoyens et les entreprises? Selon des experts et des universitaires, l’Algérie n’a pas formé une main-d’œuvre spécialisée et compétente dans ce domaine. Il faudra alors dès maintenant se préparer à changer la législation, notamment des dispositifs importants dans la loi sur le crédit et la monnaie, que le gouvernement s’attelle à réviser pour la présenter pour adoption à la mi-octobre à l’APN. Page 3 DR UNE SAISON ESTIVALE SANS RÉPIT POUR LA GENDARMERIE NATIONALE HAUSSE DE 10% DU CRIME ORGANISÉ DURANT L’ÉTÉ DERNIER L’été passé a été particulièrement chaud sur le plan de la criminalité organisée avec des hausses allant jusqu’à 350% dans certains fléaux de trafic. -

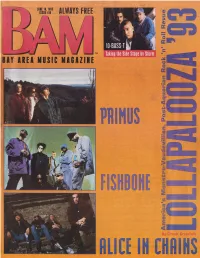

BAM Summer 93 Coverage

One World Beat By Jonathan E. Conjunto Ckspedesbe- gan at a family reunion in Oakland in August, In 1970, in a magazine called Crawdaddy, he described a kind I 1981and becameprorni- music that no one else had heard of, let alone tried to describe. nent players in the mid- He named this music heavy metal. Courtney Pine (alto and soprano saxophone, flute). '80s surge of interest in Songstresses NrDea Davenport of Brand New Heav- world beat in the Bay In 1972, he assembled, named, wrote far, ies and Carlene Anderson take this LP over the top Area. They released a with some penetrating vocals. Songs like 'When produced and managed great album, Guira con rite to Jonathan E., c/o Sound You're Near," 'Trust Me," and "Sights of the City" Son, on their own dl,54 29th St., Richmond, CA the first avowed heavy metal band, Blue Oyster Cult. are absolutely brilliant. Caldero label in 1984. 804, or email to: ieue @ For many young people, jazz is a lofty and unat- only to disappear from well'sf'ca'Â¥'s In 1975, before Rotten, before the Ramones, tainable music from the past. However, Jazzmatazz regular view. Over the past couple of years there have he discovered, fought for, succeeds in bringing generationstogether. At a recent been scattered sightings, but with the release of their recorded and forced Epic to release the first punk record, show at the DNA Lounge, the players got an over- magnificent new album, Una Sola Casa (Green Lin- whelming reception as Ayers got busy on the vibes The Dictators Go Girl Crazy. -

Faudel Retrouve Le Bled» Propos Recueillis Par Rabah Mezouane

http://www.myspace.com/faudelofficiel Nouvel Album « Bled Memory » Sortie le 18 janvier 2010 Tour : PYRPROD • 32 bd Carnot - 21000 DIJON • www.pyrprod.fr Audrey GALAS • 03 80 661 065 • [email protected] Promo tournée : Séverine MENCARELLI • 03 80 667 674 • [email protected] Thierry BINOCHE • 03 80 667 666 • [email protected] «Faudel retrouve le bled» Propos recueillis par Rabah Mezouane Faudel retrouve le bled... Dans Mon pays, un de ses titres les plus célèbres, Faudel qui dit ne pas bien connaître « ce soleil qui brûle les dunes sans fin », et pas vraiment « ce parfum de menthe et de sable brûlant », évoque tout de même la possibilité qu’il « traverse le désert pour aller voir d’où vient sa vie, dans quelles rues jouait son père ». De l’Algérie, terre d’origine de ses parents, il n’en a gardé que quelques images fulgurantes, probablement fugaces, mais ô combien enrichissantes et marquantes, en particulier les échos d’une musicalité typique à la région Ouest, captés lors d’une basta, soirée à l’oranaise, ou d’une fête de mariage. Ce patrimoine et aussi d’autres répertoires rythmant la vie à Alger, Tunis, Tlemcen, Sidi-Bel-Abbès, Le Caire ou Casablanca, n’a jamais cessé de le hanter. Trop jeune à ses débuts, il s’était contenté d’en rêver. Voilà qu’il le fait à travers un opus où émergent même des morceaux jusqu’ici enfouis dans les replis les plus intimes de sa mémoire. Non, Bled Memory ne cède pas à une pulsion dictée par un quelconque effet de mode, c’est une envie réelle de renouer avec les racines tout en restant fidèle à sa patrie de naissance et d’accueil. -

ACOUSTIC Spécial « Les 30 Ans Du Raï » Avec RACHID TAHA Samedi 30 Janvier À 16H35*

C O M M U N I Q U É D E P R E S S E 7 j a n v i e r 2 0 1 6 ACOUSTIC spécial « Les 30 ans du Raï » avec RACHID TAHA Samedi 30 janvier à 16h35* Chaque semaine, Sébastien Folin reçoit le meilleur de la création musicale francophone dans toute la diversité de ses accents, de ses rythmes et de ses visages. Référence en matière d’émission musicale, « Acoustic » ouvre les portes du célèbre studio Guillaume Tell autant aux artistes reconnus qu’aux chanteurs et groupes francophones en devenir. Depuis 13 ans, le programme musical de TV5MONDE s’est imposé comme une marque incontournable de la chaîne. A l’occasion des 30 ans du Raï, « Acoustic » recevra Rachid Taha. Il interprètera 3 titres dont deux en duo avec la chanteuse algérienne Chaba Fadela et Youness, le prince marocain du raï. Avant de s’internationaliser, le Raï a d'abord été l'expression d'un comportement social et une façon d'être Depuis, cette musique festive a sacré plusieurs stars comme Rachid Taha, Khaled, Cheb Mami, Faudel, et connut son apogée en 1996 lors de l’événement «1,2,3 soleils». Pour fêter cet anniversaire et la sortie d’un coffret 5 CD, un concert événement réunissant plus de 50 artistes aura lieu le vendredi 29 janvier 2016 au Zenith de Paris de 19h à minuit, en partenariat avec TV5MONDE. Parmi les artistes présents : Raina Rai, Cheb Hamid, Chaba Fadela, Rachid Taha, Zahouania , Cheb Bilal, Cheb Rayan , Reda Taliani , Chaba Maria , Cheb Khalass, Kamel Oujdi , RIM K (113), Algerino, Mister You, DJ Hamida, DJ Sem, DJ Kim… Avec des hommages à : Cheikha Rimitti, Cheb Hasni, Cheb Akil, Rachid Baba Ahmed.