Value for Money Analysis I-595 Corridor Roadway Improvements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storm Data Publication

FEBRUARY 2008 VOLUME 50 SSTORMTORM DDATAATA NUMBER 2 AND UNUSUAL WEATHER PHENOMENA WITH LATE REPORTS AND CORRECTIONS NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION noaa NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SATELLITE, DATA AND INFORMATION SERVICE NATIONAL CLIMATIC DATA CENTER, ASHEVILLE, NC Cover: This cover represents a few weather conditions such as snow, hurricanes, tornadoes, heavy rain and flooding that may occur in any given location any month of the year. (Photos courtesy of NCDC) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Outstanding Storm of the Month …..…………….….........……..…………..…….…..…..... 4 Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena ....…….…....…………...…...........…............ 5 Reference Notes .............……...........................……….........…..….…............................................ 278 STORM DATA (ISSN 0039-1972) National Climatic Data Center Editor: William Angel Assistant Editors: Stuart Hinson and Rhonda Herndon STORM DATA is prepared, and distributed by the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena narratives and Hurricane/Tropical Storm summaries are prepared by the National Weather Service. Monthly and annual statistics and summaries of tornado and lightning events re- sulting in deaths, injuries, and damage are compiled by the National Climatic Data Center and the National Weather Service’s (NWS) Storm Prediction Center. STORM DATA contains all confi rmed information on storms available to our staff at the time of publication. Late reports and corrections will be printed in each edition. Except for limited editing to correct grammatical errors, the data in Storm Data are published as received. Note: “None Reported” means that no severe weather occurred and “Not Received” means that no reports were received for this region at the time of printing. -

Service Patrol Handbook

FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION SERVICE PATROL HANDBOOK November 2008 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the department of transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade and manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the object of the document. i Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-HOP-08-031 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Service Patrol Handbook November 2008 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Nancy Houston, Craig Baldwin, Andrea Vann Easton, Steve Cyra, P.E., P.T.O.E., Marc Hustad, P.E., Katie Belmore, EIT 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Booz Allen Hamilton HNTB Corporation 8283 Greensboro Drive 11414 West Park Place, Suite 300 McLean, Virginia 22102 Milwaukee, WI 53224 11. Contract or Grant No. 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Federal Highway Administration, HOTO-1 Final Report U. S. Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, D. C. 20590 HOTO, FHWA 15. Supplementary Notes Paul Sullivan, FHWA Office of Operations, Office of Transportation Operations, Contracting Officer’s Technical Representative (COTR). Handbook development was performed under contract to Booz Allen Hamilton. 16. Abstract This Handbook provides an overview of the Full-Function Service Patrol (FFSP) and describes desired program characteristics from the viewpoint of an agency that is responsible for funding, managing, and operating the services. -

Key Performance Indicators in Public-Private Partnerships: a State-Of-The-Practice Report

Key Performance Indicators in Public-Private Partnerships A State-of-the-Practice Report AUSTRALIA BRITISH COLUMBIA NEW ZEALAND UNITED KINGDOM UNITED STATES Sponsored by: In cooperation with: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials National Cooperative Highway Research Program March 2011 International Technology Scanning Program NOTICE The Federal Highway Administration provides high-quality information to serve Government, industry, and the public in a manner that pro- motes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-PL-10-029 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Key Performance Indicators in March 2011 Public-Private Partnerships 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Michael Garvin, Keith Molenaar, Desiderio Navarro, Gordon Proctor 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) American Trade Initiatives 11. Contract or Grant No. P.O. Box 8228 Alexandria, VA 22306-8228 DTFH61-99-C-005 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Office of International Programs Federal Highway Administration 14. Sponsoring Agency Code U.S. Department of Transportation American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials 15. Supplementary Notes FHWA COTR: Hana Maier, Office of International Programs 16. Abstract This report provides a state-of-the-practice description of domestic and international practices for key performance indicators (KPIs) in public-private partnerships (PPPs). -

I N V E S T I N G

INVESTING IN Program Highlights | 2016 1 INVESTING IN The SIS n 2003, the Florida Legislature and Governor established the Strategic Intermodal System (SIS) to enhance Florida’s transportation mobility and Ieconomic competitiveness. The SIS is a statewide network of high-priority transportation facilities, including the State’s largest and most significant WHAT IS THE airports, spaceports, deep-water seaports, freight rail terminals, passenger rail and intercity bus terminals, rail corridors, waterways and highways. These facilities represent the state’s primary means for moving people and freight between Florida’s diverse regions, as well as between Florida and other states STRATEGIC and nations. SIS Facilities are designated through the use of objective criteria and thresholds based on quantitative measures of transportation and economic activity. These facilities meet high levels of people and goods movement and INTERMODAL generally support major flows of interregional, interstate, and international travel and commerce. Facilities that do not yet meet the established criteria and thresholds for SIS designation, but are expected to in the future are referred to as Emerging SIS. These facilities experience lower levels of people SYSTEM? and goods movement but demonstrate strong potential for future growth and development. The designated SIS and Emerging SIS includes 17 commercial service airports, two spaceports, 12 public seaports, over 2,300 miles of rail corridors, over 2,200 miles of waterways, 34 passenger terminals, seven rail freight terminals, and over 4,600 miles of highways. These hubs, corridors and connectors are the fundamental structure which satisfies the transportation needs of travelers and visitors, supports the movement of freight, and provides transportation links to external markets. -

Availability Payment Or Revenue-Risk P3 Concessions? Pros and Cons for Highway Infrastructure

Reason Foundation Policy Study No. 458 November 2017 Availability Payment or Revenue-Risk P3 Concessions? Pros and Cons for Highway Infrastructure by Robert W. Poole, Jr. Reason Foundation Reason Foundation’s mission is to advance a free society by developing, applying and promoting libertarian principles, including individual liberty, free markets and the rule of law. We use journalism and public policy research to influence the frame- works and actions of policymakers, journalists and opinion leaders. Reason Foundation’s nonpartisan public policy research promotes choice, compe- tition and a dynamic market economy as the foundation for human dignity and progress. Reason produces rigorous, peer-reviewed research and directly engages the policy process, seeking strategies that emphasize cooperation, flexibility, local knowl- edge and results. Through practical and innovative approaches to complex problems, Reason seeks to change the way people think about issues, and promote policies that allow and encourage individuals and voluntary institutions to flourish. Reason Foundation is a tax-exempt research and education organization as defined under IRS code 501(c)(3). Reason Foundation is supported by voluntary contribu- tions from individuals, foundations and corporations. The views are those of the author, not necessarily those of Reason Foundation or its trustees. Photo credit: © Lev Kropotov | Dreamstime Copyright © 2017, Reason Foundation. All rights reserved. Reason Foundation Availability Payment or Revenue-Risk P3 Concessions? Pros and Cons for Highway Infrastructure by Robert W. Poole, Jr. Executive Summary Over the past two decades, the U.S. highway sector has seen the introduction and use of a new method of procurement: the long-term public-private partnership. -

DIRECTIONS to OUR MIAMI OFFICE 777 Brickell Avenue, Suite 1370 Miami, FL 33131 Phone: 786-725-4120 Fax: 786-725-4121

DIRECTIONS TO OUR MIAMI OFFICE 777 Brickell Avenue, Suite 1370 Miami, FL 33131 Phone: 786-725-4120 Fax: 786-725-4121 Via Public Transit 777 Brickell Avenue can be reached from Miami International Airport and many locations via the Miami-Dade Transit Metrorail System. The Metrorail system is a 25-mile dual track, elevated rapid transit system that provides service to Miami International Airport (MIA) and runs from Kendall through South Miami, Coral Gables, and downtown Miami; to the Civic Center/Jackson Memorial Hospital area; and to Brownsville, Liberty City, Hialeah, and Medley in northwest Miami-Dade, with connections to Broward and Palm Beach counties at the Tri-Rail/Metrorail transfer station. The 23 accessible Metrorail stations are about one mile apart, providing easy access for bus riders, pedestrians, and passengers who are dropped off and picked up. From the Airport via Metrorail o Take the MIA Mover from the airport to the Miami-Dade Metrorail. o Once you arrive at the Metrorail take the Orange Line, southbound, to the Brickell stop. o Cross SW 1st Avenue and proceed down SW 10th Street for 3 blocks, continuing past Brickell Plaza to Brickell Avenue. o Once you arrive at Brickell, cross the intersection to the opposite side of the street and take a right. o 777 Brickell is approximately 1 – 2 blocks on your right hand side. o The building is on the corner of Brickell Avenue and SE 8 St. (Tamiami Trail) Via Metrorail in General o Take the Miami-Dade Metrorail (orange line or green line) to the Brickell stop. -

Public–Private Partnership Concessions for Highway Projects: a Primer Quality Assurance Statement

Public–Private Partnership Concessions for Highway Projects: A Primer Quality Assurance Statement The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provides high quality information to serve Government, industry, and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. Contents Chapter 1: Introduction 3 Chapter 2: How Does A P3 Concession Work? 4 Concession Goals—Public Perspective 4 Why Do Public Agencies Enter into P3 Concessions? 4 Increase Up-Front Financing Through Private Equity 5 Make Greater Total Debt Capacity Available Through Private Structure 5 Share Revenue and Risks with the Private Sector 5 Provide Incentives for Better Asset Management and On-Time and On-Budget Delivery 6 Concession Goals—Private Perspective 6 Concession Compensation—Basic Options 6 Toll and Project Revenues (from Project to Private Sector) 6 Availability Payments and Performance Payments (from Public to Private Sector) 7 Shadow Tolls (from Public to Private Sector) 7 Up-Front Payment (Private to Public Sector—for a Toll-Based Concession on an Existing Facility) 8 Concession Term—Basic Options 8 Fixed 8 Dynamic 8 Extendable 9 Chapter 3: Who Are the Primary Participants in a P3 Concession, and What Are Their Roles? 10 Primary Public Participants 10 State Legislatures 10 Governors 10 Public Sector Project Sponsor 10 -

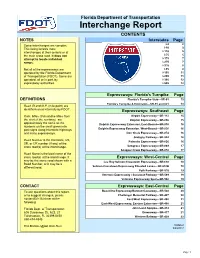

Interchange Report CONTENTS NOTES Interstates Page Some Interchanges Are Complex

Florida Department of Transportation Interchange Report CONTENTS NOTES Interstates Page Some interchanges are complex. I-4 2 This listing locates most I-10 3 interchanges at their centers or at I-110 5 the main cross road. It does not I-75 5 attempt to locate individual I-175 7 ramps. I-275 7 I-375 8 Not all of the expressways are I-95 8 operated by the Florida Department I-195 11 of Transportation (FDOT). Some are I-295 11 operated, all or in part, by I-395 12 expressway authorities. I-595 12 Expressways: Florida's Turnpike Page DEFINITIONS Florida's Turnpike Stub—SR-91 13 Florida's Turnpike & Extension—SR-91 and 821 13 Road ID and M.P. (mile point) are identifiers used internally by FDOT. Expressways: Southeast Page Cum. Miles (Cumulative Miles from Airport Expressway—SR-112 15 the start of the roadway) are Dolphin Expressway—SR-836 15 approximately the same as the Dolphin Expressway Extension, East-Bound—SR-836 16 numbers on the small green mile post signs along Interstate highways Dolphin Expressway Extension, West-Bound—SR-836 16 and many expressways. Don Shula Expressway—SR-874 16 Gratigny Parkway—SR-924 16 Road Number is the Interstate, US, Palmetto Expressway—SR-826 16 SR, or CR number (if any) of the cross road(s) at the interchange. Sawgrass Expressway—SR-869 17 Snapper Creek Expressway—SR-878 17 Road Name is the local name of the cross road(s) at the interchange. It Expressways: West-Central Page may be the same road shown with a Lee Roy Selmon-Crosstown Expressway—SR-618 18 Road Number, or it may be a different road. -

Southeast Florida Regional Transportation Plan FINAL.Indd

Final Documentation PALM BEACH MPO • BROWARD MPO • MIAMI-DADE MPO Contents Introduction . 6 Development of the Plan . 8 Plan Components Our Region and Trends . 12 Governance Data and Analysis . 14 Development and Review of 2035 Model Inputs Data and Analysis . 16 Travel Patterns and Commuting 2005 Transit Characteristics 2005 Automobile Characteristics 2005–2035 Air/Sea Characteristics Regional Transportation Network . 18 Plan Context . 22 Federal Context State Context Regional Context Local Context 2 Regional Goals . 26 Finances . 30 Financial Snapshot: Funded Projects . 36 Project Highlights Statistics Unfunded Projects . 58 Project Highlights Statistics Freight System . 66 Goals, Objectives, and Policies Identifi cation and Prioritization of Freight Projects Transit . 76 Public Involvement . 78 Public Involvement Conclusion . 80 3 Participants Palm Beach Metropolitan Planning Organization 2300 N. Jog Road, 4th Floor West Palm Beach, Florida 33411-2749 Broward Metropolitan Planning Organization 100 West Cypress Creek Road, Suite 850 Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33309 Miami-Dade Metropolitan Planning Organization 111 N.W. First Street , Suite 910 Miami, Florida 33128-1999 4 Funding Partners Legal Information and Project Team and Contact Information The three Southeast Florida MPO’s provided funding for this The preparation of this report has been fi nanced in part fi rst Regional Long Range Transportation Plan: the Palm through grants from the Federal Highway Administration and Beach MPO, the Broward MPO, and the Miami-Dade MPO. Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transporta- tion, under the State Planning and Research Program, Section Other regional partners who particpated in the development 505 [or Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f)] of Title of this plan include: 23, U.S. -

Pond Apple Slough Preliminary Assessment & Rehydration Test

Pond Apple Slough Preliminary Assessment and Rehydration Test Technical Publication WS-10 Cynthia J. Gefvert and Steve L. Krupa, P.G. December 2001 South Florida Water Management District 3301 Gun Club Road West Palm Beach, FL 33306 (561) 686-8800 www.sfwmd.gov Pond Apple Slough Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Pond Apple Slough is a 112-acre urban wetland in eastern Broward County. The unique characteristics of Pond Apple Slough can be attributed to the fact that it is part of the forested drainageway formed near the New River break in the coastal ridge, along the edge of the remnant Everglades. Most wetlands in eastern Broward County are man-made excavated systems, generally less than five acres in size. The health of Pond Apple Slough was impaired when its natural overland flow of fresh water was greatly diminished due to years of development and construction of Interstate 595 (I-595), the Broward County Resource Recovery Center, and the I-595/State Road 441 interchange. The South Florida Water Management District (District), along with Broward County and other interested parties, has been a participant in the Pond Apple Slough Working Group, an association created in 1991, dedicated to restoration of the slough. The work of the PAS Working Group was funded by mitigation funds made available to Broward County in a 1991 agreement with the Homart Development Corporation. This work included a baseline study to determine the health and needs of the slough, removal of exotics from the area, and development of a long-term management plan to maintain a healthy, freshwater ecosystem. -

Statewide Road Ranger Survey for Incident Responders

Statewide Road Ranger Survey for Incident Responders Table of Contents Road Ranger Background………………………………. 3 Purpose of Survey……………………………………….. 4 Survey Methodology…………………………………….. 5 Survey Distribution………………………………………. 6 Survey Data Collection………………………………….. 7 Measurement Methodology…………………………….. 7 Survey Results…………………………………………… 8 Conclusion………………………………………………… 17 Appendix A – Original Survey…………………………... 20 Appendix B – Additional Data Questions 6-15………... 25 Appendix C – Survey Comments………………………. 33 Road Ranger District Contacts…………………………. 41 This document was developed and produced by the Florida Department of Transportation, Traffic Engineering and Operations Office, Traffic Incident Management2 and Commercial Vehicle Operations Program. If you would like to use or reprint any of the content in this document, please contact Shawn Kinney at (850) 410-5600, or email: [email protected]. Statewide Road Ranger Survey for Incident Responders Road Ranger Background Florida’s Road Ranger service patrol program (Road Rangers) is a free service offered by the Florida Department of Transportation (Department) and other transportation agency partners. The Department initially used the program to manage vehicle incidents in construction zones and has since expanded to all types of incident responses, becoming one of the most effective elements of the Department's Traffic Incident Management (TIM) Program. Road Rangers provide a “We love these people. They are our safety net and guardian when we are on the Highway.” direct service to motorists by quickly clearing minor incidents from travel lanes in Quote taken from the 2015/16 survey close coordination with the Florida Highway Patrol (FHP) and other law enforcement agencies. They also assist stranded motorists with basic services, such as furnishing a limited amount of fuel, assisting with tire changes, and helping with other types of minor vehicle repairs. -

2035 Broward Transformation Long Range Transportaiton Plan

FINAL REPORT BROWARD MPO Commissioner Daniel J. Stermer Chair, District 5, City of Weston Mayor Rae Carole Armstrong Vice Chair, District 3, City of Plantation Gregory Stuart Executive Director Michael Ronskavitz Deputy Executive Director District 1 Commissioner Roy Gold City of Coral Springs Commissioner Harry Dressler City of Tamarac Commissioner Joseph Varsallone Alternate, City of Margate Commissioner Gary Frankel Alternate, City of North Lauderdale Commissioner David Rosenof Alternate, City of Parkland District 2 Commissioner George Brummer City of Pompano Beach Commissioner Bill Ganz City of Deerfi eld Beach Mayor Marilyn Gerber Alternate, City of Coconut Creek Commissioner Sandy Johnson Alternate, City of Lighthouse Point Commissioner Birute Ann Clottey Alternate, Town of Lauderdale-by-the-Sea Vice Mayor Dan Dodge Alternate, Town of Hillsboro Beach District 3 Vice Mayor Charlotte Rodstrom City of Fort Lauderdale Vice Mayor Bruce Roberts City of Fort Lauderdale Mayor Richard J. Kaplan City of Lauderhill Commissioner Lawrence A. Sofi eld City of Sunrise Commissioner David W. Shomers Alternate, City of Lauderdale Lakes Commissioner Allegra Webb Murphy Alternate, City of Oakland Park Commissioner Tom Green Alternate, City of Wilton Manors Commissioner Douglas Hodgson Alternate, Village of Sea Ranch Lakes District 4 Commissioner Richard Blattner City of Hollywood Mayor Joy Cooper Alternate, City of Hallandale Mayor Anne Castro Alternate, City of Dania Beach District 5 Councilmember Bryan Caletka Town of Davie Commissioner Troy Samuels City of Miramar Mayor Frank C. Ortis City of Pembroke Pines Commissioner John Sims Alternate, City of Cooper City Commissioner Freddy Fisikelli Alternate, Town of Southwest Ranches Vice Mayor Ashira Mohammed Alternate, Town of Pembroke Park Mayor Eric H.