The Revered Heiau of Pu'ukohola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dread Taboo, Human Sacrifice, and Pearl Harbor

The Dread Taboo, Human Sacrifice, and Pearl Harbor RDKHennan The word taboo, or tabu, is well known to everyone, but it is especially interesting that it is one of but two or possibly three words from the Polynesian language to have been adopted by the English-speaking world. While the original meaning of the taboo was "Sacred" or "Set apart," usage has given it a decidedly secular meaning, and it has become a part of everyday speech all over the world. In the Hawaiian lan guage the word is "kapu," and in Honolulu we often see a sign on a newly planted lawn or in a park that reads, not, "Keep off the Grass," but, "Kapu." And to understand the history and character of the Hawaiian people, and be able to interpret many things in our modern life in these islands, one must have some knowledge of the story of the taboo in Hawaii. ANTOINETTE WITHINGTON, "The Dread Taboo," in Hawaiian Tapestry Captain Cook's arrival in the Hawaiian Islands signaled more than just the arrival of western geographical and scientific order; it was the arrival of British social and political order, of British law and order as well. From Cook onward, westerners coming to the islands used their own social civil codes as a basis to judge, interpret, describe, and almost uniformly condemn Hawaiian social and civil codes. With this condemnation, west erners justified the imposition of their own order on the Hawaiians, lead ing to a justification of colonialism and the loss of land and power for the indigenous peoples. -

Visibility Analysis of Oahu Heiau

Visibility Analysis of Oahu Heiau A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN GEOGRAPHY May 2012 By Kepa Lyman Thesis Committee: Matthew McGranaghan, Chair Hong Jiang William Chapman Keywords: heiau, intervisibility, viewshed analysis Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................... III LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................... IV INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 5 CHAPTER OUTLINE ..................................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER I. HAWAIIAN HEIAU ............................................................................................................ 8 HEIAU AS SYMBOL ..................................................................................................................................... 8 HEIAU AS FORTRESS ................................................................................................................................. 12 TYPES ...................................................................................................................................................... -

The Hawaiian Political Transformation from 1770 to 1796

3 The Hawaiian Political Transformation from 1770 to 1796 No one alive in 1778 would have predicted that the Hawaiian Islands would be unified in their lifetime, or that Kamehameha would be the chief to bring it about. To understand how the potential for unification noted by scholars became a reality requires a detailed examination of political and military structural transformations that picked up momentum after 1770. Robert Hommon discusses global writings on warfare and state formation in The Ancient Hawaiian State, including the work of Charles Tilly and Robert Carneiro, and makes a strong connection between the two. Hommon concludes that warfare was a causative link but not a crucial factor in Hawaiian state formation because war was pursued by states and non-states alike. Rather, to Hommon, the key influence on Hawaiian state formation was the political innovation of ‘both holding centralised political power and delegating it’.1 This and the following chapter contest Hommon’s dichotomy by arguing that changes to the nature of political and military power in the late 18th century were interrelated. Escalating chiefly rivalries spurred military reforms and forced chiefs to delegate authority to accommodate a structure of warfare that mobilised and relied upon a greater proportion of the polities’ residents and resources. Hawaiian society became more militarised as chiefs threw off the vestiges 1 Hommon (2013), pp. 238–40. 85 TRANSFORMING Hawai‘I of sacred power that had come to constrain them, and altered their warfare to make it more efficient, even though this resulted in an erosion of chiefly status on the battlefield. -

Ad E& MAY 2 6 1967

FEBRUARY, 1966 254 &Ad e& MAY 2 6 1967 Amstrong, Richard,presents census report 145; Minister of Public Abbott, Dr. Agatin 173 Instruction 22k; 227, 233, 235, 236, Abortion 205 23 7 About A Remarkable Stranger, Story 7 Arnlstrong, Mrs. Richard 227 Adms, Capt . Alexander, loyal supporter Armstrong, Sam, son of Richard 224 of Kamehameha I 95; 96, 136 Ashford, Volney ,threatens Kalakaua 44 Adans, E.P., auctioneer 84 Ashford and Ashford 26 Adams, Romanzo, 59, 62, 110, 111, ll3, Asiatic cholera 113 Ilk, 144, 146, 148, 149, 204, 26 ---Askold, Russian corvette 105, 109 Adams Gardens 95 Astor, John Jacob 194, 195 Adams Lane 95 Astoria, fur trading post 195, 196 Adobe, use of 130 Atherton, F.C, 142 ---mc-Advertiser 84, 85 Attorney General file 38 Agriculture, Dept. of 61 Auction of Court House on Queen Street kguiar, Ernest Fa 156 85 Aiu, Maiki 173 Auhea, Chiefess-Premier 132, 133 illmeda, Mrs. Frank 169, 172 Auld, Andrew 223 Alapai-nui, Chief of Hawaii 126 Austin, James We 29 klapai Street 233 Automobile, first in islands 47 Alapa Regiment 171 ---Albert, barkentine 211 kle,xander, Xary 7 Alexander, W.D., disputes Adams 1 claim Bailey, Edward 169; oil paintings by 2s originator of flag 96 170: 171 Alexander, Rev. W.P., estimates birth mile: House, Wailuku 169, 170, 171 and death rates 110; 203 Bailey paintings 170, 171 Alexander Liholiho SEE: Kamehameha IV Baker, Ray Jerome ,photographer 80, 87, 7 rn Aliiolani Hale 1, 41 opens 84 1 (J- Allen, E.H., U.S. Consul 223, 228 Baker, T.J. -

Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui

On the Cloak of Kings: Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui By Alexander Underhill Baer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Patrick V. Kirch Professor Kent G. Lightfoot Professor Anthony R. Byrne Spring 2015 On the Cloak of Kings: Agriculture, Power, and Community in Kaupō, Maui Copyright © 2015 By Alexander Underhill Baer Table of Contents List of Figures iv List of Tables viii Acknowledgements x CHAPTER I: OPENING THE WATERS OF KAUPŌ Introduction 1 Kaupō’s Natural and Historical Settings 3 Geography and Environment 4 Regional Ethnohistory 5 Plan of the Dissertation 7 CHAPTER 2: UNDERSTANDING KAUPŌ: THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO THE STUDY OF POWER AND PRODUCTION Introduction 9 Last of the Primary States 10 Of Chiefdoms and States 12 Us Versus Them: Evolutionism Prior to 1960 14 The Evolution Revolution: Evolutionism and the New Archaeology 18 Evolution Evolves: Divergent Approaches from the 1990s Through Today 28 Agriculture and Production in the Development of Social Complexity 32 Lay of the Landscape 36 CHAPTER 3: MAPPING HISTORY: KAUPŌ IN MAPS AND THE MAHELE Introduction 39 Social and Spatial Organization in Polynesia 40 Breaking with the Past: New Forms of Social Organization and Land Distribution 42 The Great Mahele 47 Historic Maps of Hawaiʻi and Kaupō 51 Kalama Map, 1838 55 Hawaiian Government Surveys and Maps 61 Post-Mapping: Kaupō Land -

Taro As the Symbol of Postcolonial Hawaiian Identity ______

Growing resistance: Taro as the symbol of postcolonial Hawaiian identity __________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology University of Canterbury __________ In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts __________ by Charles Pipes February 2020 ii iii Abstract Taro is a root vegetable that has held important dietary, spiritual, and social roles with Native Hawaiian culture for centuries. The cultivation and management of the taro plant was a significant foundation of ancient Hawaiian society. Following the 19th century Western colonization of Hawaii, and the ensuing degradation of the indigenous culture, taro cultivation went into a steep decline as a result of land alienation, commercialization, and resources being designated for alternative, non- native crops. In the years following annexation by the United States, there was a growing Hawaiian identity and sovereignty movement. This thesis examines how taro became a potent symbol of that movement and Indigenous Hawaiian resistance to Western hegemony. The thesis will examine taro’s role as a symbol of resistance by analyzing the plant’s traditional uses and cultivation methods, as well as the manner in which Hawaiian taro was displaced by colonial influence. This resistance, modeled after the Civil Rights Movement and American Indian Movement in the United States, used environmental, spiritual, and cosmological themes to illustrate the Hawaiian movement’s objectives. Taro cultivation, encapsulating nearly every aspect of traditional Hawaiian society and environment, became a subtle form of nonviolent protest. To examine taro farming from this perspective, the plant’s socioeconomic, spiritual, and biological aspects will be explored. -

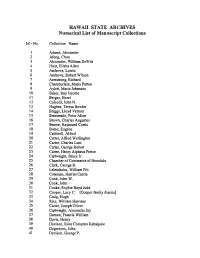

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections M-No. Collection Name 1 Adams, Alexander 2 Afong, Chun 3 Alexander, WilliamDe Witt 4 Hunt, Elisha Allen 5 Andrews, Lorrin 6 Andrews, Robert Wilson 7 Armstrong,Richard 8 Chamberlain, MariaPatton 9 Aylett, Marie Johannes 10 Baker, Ray Jerome 11 Berger, Henri 12 Colcord, John N. 13 Hughes, Teresa Bowler 14 Briggs, Lloyd Vernon 15 Brinsmade, Peter Allen 16 Brown, CharlesAugustus 17 Brown, Raymond Curtis 18 Burns, Eugene 19 Caldwell, Alfred 20 Carter, AlfredWellington 21 Carter,Charles Lunt 22 Carter, George Robert 23 Carter, Henry Alpheus Pierce 24 Cartwright, Bruce Jr. 25 Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu 26 Clark, George R. 27 Leleiohoku, William Pitt 28 Coleman, HarrietCastle 29 Cook, John W. 30 Cook, John 31 Cooke, Sophie Boyd Judd 32 Cooper, Lucy C. [Cooper family diaries] 33 Craig, Hugh 34 Rice, William Harrison 35 Carter,Joseph Oliver 36 Cartwright,Alexander Joy 37 Damon, Francis William 38 Davis, Henry 39 Davison, Rose Compton Kahaipule 40 Degreaves, John 41 Denison, George P. HAWAIi STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript collections M-No. Collection Name 42 Dimond, Henry 43 Dole, Sanford Ballard 44 Dutton, Joseph (Ira Barnes) 45 Emma, Queen 46 Ford, Seth Porter, M.D. 47 Frasher, Charles E. 48 Gibson, Walter Murray 49 Giffard, Walter Le Montais 50 Whitney, HenryM. 51 Goodale, William Whitmore 52 Green, Mary 53 Gulick, Charles Thomas 54 Hamblet, Nicholas 55 Harding, George 56 Hartwell,Alfred Stedman 57 Hasslocher, Eugen 58 Hatch, FrancisMarch 59 Hawaiian Chiefs 60 Coan, Titus 61 Heuck, Theodor Christopher 62 Hitchcock, Edward Griffin 63 Hoffinan, Theodore 64 Honolulu Fire Department 65 Holt, John Dominis 66 Holmes, Oliver 67 Houston, Pinao G. -

Heiau and Noted Places of the Makena–Keone'ö'io Region

HEIAU AND NOTED PLACES OF THE MAKENA–KEONE‘Ö‘IO REGION OF HONUA‘ULA DESCRIBED IN HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS (1870S-1930S) This section of the study presents readers with verbatim accounts of heiau and other cultural properties as described by researchers in the region of Honua‘ula—with emphasis on the ahupua‘a of Ka‘eo—since 1916. Detailed research was conducted in collections of the Bishop Museum, Maui Historical Society, Mission Children’s Society Library-Hawaiian Historical Society, and Hawaii State Archives as a part of this study. While a significant collection of references to traditional-cultural properties and historical sites was found, only limited and inconclusive documentation pertaining to the “Kalani Heiau” (Site 196) on the Garcia family property was located. Except for documentation associated with two kuleana awarded during the Mähele of 1848, no other information pertaining to sites on the property was located in the historical accounts. In regards to the “Kalani Heiau,” the earliest reference to a heiau of that name was made in 1916, though the site was not visited, or the specific location given. It was not until 1929, that a specific location for “Kalani Heiau” was recorded by W. Walker (Walker, ms. 1930-31), who conducted an archaeological survey on Maui, for the Bishop Museum. The location of Walker’s “Site No. 196” coincides with that of the “Kalani Heiau” on the Garcia property, but it also coincides with the area claimed by Mähele Awardee, Maaweiki (Helu 3676)—a portion of the claim was awarded as a house lot for Maaweiki. While only limited information of the heiau, and other sites on the property could be located, it is clear that Site No. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

Microsoftxwordx ... Gexversjonenxx20.06.07.Pdf

The Consequences of Eating With Men Hawaiian Women and the Challenges of Cultural Transformation By Paulina Natalia Dudzinska A thesis submitted for the Cand. Philol. Degree in History of Religions Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages University of Oslo Spring 2007 2 Summary Before 1819 Hawaiian society was ruled by a system of ritual laws called kapu. One of these, the aikapu (sacred eating), required men and women to eat separately. Because eating was ritual, some food items, symbolically associated with male deities, were forbidden to women. It was believed that women had a “haumia” (traditionally translated as “defiling”) effect on the male manifestations of the divine and were, as a consequence, barred from direct worship of male gods and work tasks such as agriculture and cooking. In Western history writing, Hawaiian women always presented a certain paradox. Although submitted to aikapu ideology, that was considered devaluing by Western historians, women were nevertheless always present in public affairs. They engaged in the same activities as men, often together with men. They practised sports, went to war and assumed public leadership roles competing with men for power. Ruling queens and other powerful chiefesses appear frequently in Hawaiian history, chants and myths. The Hawaiians did not seem to expect different behaviour of men and women, except perhaps in ritual contexts. Rank transcended any potential asymmetry of genders and sometimes the highest-ranking women were considered above the kapu system, even the aikapu. In 1819, after 40 years of contact with the foreigners, powerful Hawaiian queens decided to abolish the kapu system, including the aikapu. -

Sharks Upon the Land Seth Archer Index More Information Www

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17456-6 — Sharks upon the Land Seth Archer Index More Information Index ABCFM (American Board of ‘anā‘anā (sorcery), 109–10, 171, 172, 220 Commissioners for Foreign Missions), Andrews, Seth, 218 148, 152, 179, 187, 196, 210, 224 animal diseases, 28, 58–60 abortion, 220 annexation by US, 231, 233–34 adoption (hānai), 141, 181, 234 Aotearoa. See New Zealand adultery, 223 Arago, Jacques, 137 afterlife, 170, 200 Armstrong, Clarissa, 210 ahulau (epidemic), 101 Armstrong, Rev. Richard, 197, 207, 209, ‘aiea, 98–99 216, 220, 227 ‘Aikanaka, 187, 211 Auna, 153, 155 aikāne (male attendants), 49–50 ‘awa (kava), 28–29, 80, 81–82, 96, 97, ‘ai kapu (eating taboo), 31, 98–99, 124, 135, 139, 186 127, 129, 139–40, 141, 142, 143 bacterial diseases, 46–47 Albert, Prince, 232 Baldwin, Dwight, 216, 221, 228 alcohol consumption, 115–16, baptism, 131–33, 139, 147, 153, 162, 121, 122, 124, 135, 180, 186, 177–78, 183, 226 189, 228–29 Bayly, William, 44 Alexander I, Tsar of Russia, 95, 124 Beale, William, 195–96 ali‘i (chiefs) Beechey, Capt. Richard, 177 aikāne attendants, 49–50 Bell, Edward, 71, 72–73, 74 consumption, 122–24 Beresford, William, 56, 81 divine kingship, 27, 35 Bible, 167, 168 fatalism, 181, 182–83 Bingham, Hiram, 149, 150, 175, 177, 195 genealogy, 23, 26 Bingham, Sybil, 155, 195 kapu system, 64, 125–26 birth defects, 52 medicine and healing, 109 birth rate, 206, 217, 225, 233 mortality rates, 221 Bishop, Rev. Artemas, 198, 206, 208 relations with Britons, 40, 64 Bishop, Elizabeth Edwards, 159 sexual politics, 87 Blaisdell, Richard Kekuni, 109 Vancouver accounts, 70, 84 Blatchley, Abraham, 196 venereal disease, 49 Blonde (ship), 176 women’s role, 211 Boelen, Capt. -

Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6t1nb227 No online items Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Brooke M. Black. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2002 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: mssEMR 1-1323 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers Dates (inclusive): 1766-1944 Bulk dates: 1860-1915 Collection Number: mssEMR 1-1323 Creator: Emerson, Nathaniel Bright, 1839-1915. Extent: 1,887 items. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Hawaiian physician and author Nathaniel Bright Emerson (1839-1915), including a a wide range of material such as research material for his major publications about Hawaiian myths, songs, and history, manuscripts, diaries, notebooks, correspondence, and family papers. The subjects covered in this collection are: Emerson family history; the American Civil War and army hospitals; Hawaiian ethnology and culture; the Hawaiian revolutions of 1893 and 1895; Hawaiian politics; Hawaiian history; Polynesian history; Hawaiian mele; the Hawaiian hula; leprosy and the leper colony on Molokai; and Hawaiian mythology and folklore. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities.