Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vashon Island News-Record

Vashon Island News-Record COUNTY, FRIDAY, MAY 28, 1926 $2.00 PER YEAR » VOL. X, NO. 32 VASHON, KING WASHINGTON. ROSE CLUB SHOW MRS KIRKLAND IS COMMENCEMERT PROGRAM GREAT SUCCESS SEVERELY INJURED COMMENCEMERT PROGRAM a competitive held In exhibit home from the under the auspices of the Vashon While returning [eights Rose Club in the Com- Vashon IHigh School Commence- BURTON HIGH SCHOOL munity Home on Saturday even- ment exercises last Wednesday VASHON HIGH SCHOOL ing about 100 were on ex- evening, during entries and a shower of Evening, May 26 Friday Evening, May 28, 1926 hibit. The winners were: Sweep- rain which made the pavement Wednesday stakes won by Mrs, Sam Kelly on wet and slippery, Mrs, B. P. Kirk- VASHON ISLAND COMMUNITY HOME an ‘‘lndian Butterfly’’ variety. land was struck by a car bemng first was won Mrs, Rhn Vashon, Washington Mapah Hiergeh The prize by driven by Louis Bailey and o Tdsiniaiiowdmsealatii Tradke vlyne =0 s Kelly on a basket of “‘The Cloth severly injured. She was walking ; Nt ... iR sHeanu Rava ret Invocation R e of Gold’ roses. She also won toward home with her daughter. st iace i s i T Alntatony e Hal ansTe osdal first on a basket of peonies. Mrs. Leah, and Mr. and Mrs. Morgan Oration, **Ambition?? Lo Yetive H.-Woody F. A. Hathaway won first prize who were driving in the same di- William Merrill Smith, Superintendent Presiding on a vase of **Cherokee’’ riection, and called to her Essay, ‘‘Roman and Greek Arvchitecture’ ... Oge F. Jensen stopped Progessional ll)svs‘ sininatd Sn sLo ie b Banaarolle A, Mrs, Lincoln won first prize on a and her child to get in and ride Sarsusie e Piano Solo .. -

Georg Friedrich Händel

GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL ~ ORATORIUM JOSHUA This live recording is part of a cycle of oratorios, masses and other grand works, performed in the basilica of Maulbronn Abbey under the direction of Jürgen Budday. The series combines authentically perfor- Die vorliegende Konzertaufnahme ist Teil eines Zyklus von Oratorien und med oratorios and masses with the optimal acoustics and atmosphere Messen, die Jürgen Budday im Rahmen der Klosterkonzerte Maulbronn über of this unique monastic church. This ideal location demands the trans- mehrere Jahre hinweg aufführte. Die Reihe verbindet Musik in historischer parency of playing and the interpretive unveiling of the rhetoric intima- Aufführungspraxis mit dem akustisch und atmosphärisch optimal geeigne- tions of the composition, which is especially aided by the historically ten Raum der einzigartigen Klosterkirche des Weltkulturerbes Kloster Maul- informed performance. The music is exclusively performed on recon- bronn. Dieser Idealort verlangt geradezu nach der Durchsichtigkeit des Mu- structed historical instruments, which are tuned to the pitch customary sizierens und der interpretatorischen Freilegung der rhetorischen Gestik der in the composer‘s lifetimes (this performance is tuned in a‘ = 415 Hz). Komposition, wie sie durch die historische Aufführungspraxis in besonderer Weise gewährleistet ist. So wird ausschließlich mit rekonstruierten histori- schen Instrumenten musiziert, die in den zu Lebzeiten der Komponisten üb- lichen Tonhöhen gestimmt sind (in dieser Aufführung a‘ = 415 Hz). FURTHER INFORMATION TO THIS PUBLICATION AND THE WHOLE CATALOGUE UNDER WWW.KUK-ART.COM Publishing Authentic Classical Concerts entails for us capturing and recording for posterity out- standing performances and concerts. The performers, audience, opus and room enter into an inti- mate dialogue that in its form and expression, its atmosphere, is unique and unrepeatable. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Ttrickrarebooks.Com Member ABAA, SLAM & ILAB B MK A G Hard Hat Area

Thinking straight . No. . No. (outside front cover). The beauty in science (title-page). No. . R I C K T T R I A c K R E M B E O C O U K R S B C 7 A 5 T A L O G Sabine Avenue Narberth, Pennsylvania Tel. -- Fax -- info @mckittrickrarebooks.com www.mckittrickrarebooks.com Member ABAA, SLAM & ILAB B MK A G Hard Hat Area . No. 1. Alberti, Leone Battista. De Re Aedificatoria . Florence, Nicolaus Lau - rentii Alamanus December . Folio ( x mm.). [ ] leaves. Roman type ( Rb), lines per page (a few leaves or ), seven-line capital spaces with printed guide letters, most quires with printed catch - words, some quire signatures printed on the last line of text. th-century Italian vellum over stiff paper boards, ms. spine title, edges sprinkled brown. See facing illustration .$ . First Edition, first state: “ ” (PMM ). This is the first exposition of the scientific theo - ries of the Renaissance on architecture, the earliest printed example of town planning, the first description in the Renaissance of the ideal church and the first printed proposals for hospital design. He discusses frescoes, marble sculpture, windows, staircases, prisons, canals, gardens, machinery, warehouses, markets, arsenals, theaters…. He advocates for hospitals with small private rooms, not long wards, and with segregated facilities for the poor, the sick, the contagious and the noninfectious. “ ” ( PMM ), as well as important restoration projects like the side aisles of Saint Peter’s in Rome. A modest copy (washed, portions of six margins and one corner supplied, three quires foxed, scattered marginal spotting, loss of a half dozen letters, a few leaves lightly stained, two effaced stamps), book - plate of Sergio Colombi with his acquisition date of .X. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

PNWA E-Notes

PNWA E-Notes http://ui.constantcontact.com/visualeditor/visual_editor_preview.jsp?agent... Having trouble viewing this email? Click here You may unsubscribe if you no longer wish to receive our emails. PACIFIC NORTHWEST WRITERS ASSOCIATION MARCH E-NOTES March E-Notes MARCH 2010 E-NOTES: PNWA News E-Notes is your monthly electronic newsletter full of the latest news about the literary world. Our newsletter is a PNWA Member Benefit. Contests/Submissions Classes/Workshops Please send us an email if you would like to place an announcement in next month's E-Notes: [email protected] Events/Speakers Miscellaneous (Announcements must be received by the 19th of the previous month to be included). PNWA NEWS: MONTHLY SPEAKER MEETING: Thursday, March 18, 2010 Chinook Middle School @ 7:00 P.M. (2001 98th Ave NE, Bellevue, WA 98004) Topic & Speaker will be announced soon on the main page of our website (www.pnwa.org). PNWA Member Peter Bacho Leaving Yesler, Pleasure Boat Studio, Softcover $16.00 (250pp) (ISBN#: 978-1-929355570) Leaving Yesler encounters seventeen year-old Bobby Vincente in the wake of his older brother's military death; faced with the challenge of caring for his aging father, this young man from urban Seattle's housing projects is forced to take control of his life and identity as he traverses a period of life-altering change marked by new interests, new challenges, and ultimately, new life. Author Peter Bacho, a two-time winner of the American Book Award, explores themes of belief/disbelief, arrival/departure, and love/violence, through which he achieves a portrait of embodied strength in his protagonist. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non- commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Katarzyna Kosior (2017) "Becoming and Queen in Early Modern Europe: East and West", University of Southampton, Faculty of the Humanities, History Department, PhD Thesis, 257 pages. University of Southampton FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Becoming a Queen in Early Modern Europe East and West KATARZYNA KOSIOR Doctor of Philosophy in History 2017 ~ 2 ~ UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES History Doctor of Philosophy BECOMING A QUEEN IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE: EAST AND WEST Katarzyna Kosior My thesis approaches sixteenth-century European queenship through an analysis of the ceremonies and rituals accompanying the marriages of Polish and French queens consort: betrothal, wedding, coronation and childbirth. The thesis explores the importance of these events for queens as both a personal and public experience, and questions the existence of distinctly Western and Eastern styles of queenship. A comparative study of ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ ceremony in the sixteenth century has never been attempted before and sixteenth- century Polish queens usually do not appear in any collective works about queenship, even those which claim to have a pan-European focus. -

Phab Gold Rose Order Form Refer to Price List and Delivery Notes on Page 4

Phab Gold Rose Price List PhabPhab GoldGold RoseRose and Delivery Charges Phab celebrates its Diamond Jubilee in 2017 We aim to promote the Charity’s wonderful work with a profusion of Bare Root Roses £9.00 each Phab Gold roses planted in private and public gardens and spaces Potted Roses £9.95 each during 2017. And to achieve this we are enlisting the help of gardeners all over Britain! Postage and Packing: Up to 10 bare root roses £6.95 Up to 3 potted roses £8.95 Each additional potted rose £2.50 UK mainline prices only For larger orders, please phone for confirmation of delivery charges. These lovely roses will be produced in limited numbers so it is important to reserve your plants well in advance. Bare root roses can be planted any time between end of October and mid March (weather permitting). ORDERS PLACED FOR BARE ROOT ROSES WILL BE DELIVERED FROM NOVEMBER TO MID MARCH. Orders for potted roses can be delivered all year round. Special delivery dates and gift cards can be arranged. Phab will benefit from a donation for each rose planted, generating vital funds for the Charity’s work with children, young people and adults with and without disabilities. You can support the work of Phab and also enjoy this wonderful scented rose by planting a single bush or maybe a whole flower-bed of Phab Gold. Charity No. 283931 Phab inspires and supports children and adults Phab inspires and supports children and adults with and without disabilities with and without disabilities to make more of life together to make more of life together Charity No. -

Los Motores Aeroespaciales, A-Z

Sponsored by L’Aeroteca - BARCELONA ISBN 978-84-608-7523-9 < aeroteca.com > Depósito Legal B 9066-2016 Título: Los Motores Aeroespaciales A-Z. © Parte/Vers: 1/12 Página: 1 Autor: Ricardo Miguel Vidal Edición 2018-V12 = Rev. 01 Los Motores Aeroespaciales, A-Z (The Aerospace En- gines, A-Z) Versión 12 2018 por Ricardo Miguel Vidal * * * -MOTOR: Máquina que transforma en movimiento la energía que recibe. (sea química, eléctrica, vapor...) Sponsored by L’Aeroteca - BARCELONA ISBN 978-84-608-7523-9 Este facsímil es < aeroteca.com > Depósito Legal B 9066-2016 ORIGINAL si la Título: Los Motores Aeroespaciales A-Z. © página anterior tiene Parte/Vers: 1/12 Página: 2 el sello con tinta Autor: Ricardo Miguel Vidal VERDE Edición: 2018-V12 = Rev. 01 Presentación de la edición 2018-V12 (Incluye todas las anteriores versiones y sus Apéndices) La edición 2003 era una publicación en partes que se archiva en Binders por el propio lector (2,3,4 anillas, etc), anchos o estrechos y del color que desease durante el acopio parcial de la edición. Se entregaba por grupos de hojas impresas a una cara (edición 2003), a incluir en los Binders (archivadores). Cada hoja era sustituíble en el futuro si aparecía una nueva misma hoja ampliada o corregida. Este sistema de anillas admitia nuevas páginas con información adicional. Una hoja con adhesivos para portada y lomo identifi caba cada volumen provisional. Las tapas defi nitivas fueron metálicas, y se entregaraban con el 4 º volumen. O con la publicación completa desde el año 2005 en adelante. -Las Publicaciones -parcial y completa- están protegidas legalmente y mediante un sello de tinta especial color VERDE se identifi can los originales. -

TURKEY APPEALS to POWERS Iiilhhn

Sf From Ban Frantlscol uood Is Wllhilmlim .. Odnb.r S One essential of a.lverllilno Tar Ben Franclseol persistency. by advertising can D merchant Hiitinliiliiti . (Ktnlnr 3 Only From Vancouver. secure wide distribution. Evening Only with wide distribution can h October II Btjbletin Mukurii For Vancouverl maintain low priets and hold the trade. 'hi In ml In OrtnberJ2 3:30 EDITION Publicity Is Purely a Matter of Business ESTABLISHED 1882. No. 5045. 22 PAGES. HONOLULU, TERRITORY OF HAWAII, SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 1911. 22 PAGES. PRICE 5 CENTS. f TURKEY APPEALS TO POWERS U. S. To AID HER ITALY'S DEADLY ROW ATTENDS OPENING OF COLLEGE BUILDING BIDS Campbell's 1 r . : IATTACK ALREADY ' Scheme Is WINNING THE WAR Beaten I tAasoclnled Press Cable.') pii m:u i;n woitK I y ) ;' TRIPOLI, Turkey, Sept. 30. Turkey hat appealed to the powers. iiilhhn 5 With Italy's twlft attack, already tending the Turkish war vettels to liillllill lln KupTlnli ihIpiiI Miiraton the bottom of the ocean, cut olf from gaining access to her land forces, tho ('iiiiIh-I- I llRiirnl II Empire appealed to tho world powers to Interfere in the fight, Ottoman has first, America has been asked to care for the Turks in Italy as a 7JU, ' " 4iMHHHMHBaanMSMsaanMaMsajsjajS I'niii.iil ei'wir tj skin and to guard them from tho Italians. ntlirrn nflrruninl fj Hoh ! nil of llii.ltli ii nil TRIPOLI, Sept. 30. The bombardment of the fort here has begun by tht S.inlliiry Coi.iiiiIhiiIiiii HRiiriHt It: Viililliiilo llrnl, Inl-li- 'l Italian squadron. COLLEGE1 EXTERIOR VIEW OF NEW OF HAWAII BUILDING, FOR WHICH BIDS WERE OPENED TODAY komuhI. -

Entityname Filenumber "D" PLATINUM CONTRACTING SERVICES, LLC L00005029984 #Becauseoffutbol L.L.C. L00005424745 #KIDSMA

EntityName FileNumber "D" PLATINUM CONTRACTING SERVICES, LLC L00005029984 #BecauseOfFutbol L.L.C. L00005424745 #KIDSMATTERTOO, INC N00005532057 #LIVEDOPE Movement N00005462346 (2nd) Second Chance for All N00004919509 (H.E.L.P) Helping Earth Loving People N00005068586 1 800 Water Damage North America, LLC L00005531281 1 city, LLC L00005556347 1 DUPONT CIRCLE, LLC L00005471609 1 HOPE LLC L00005518975 1 Missouri Avenue NW LLC L00005547423 1 P STREET NW LLC L42692 1 S Realty Trust LLC L00005451539 1 SOURCE CONSULTING Inc. 254012 1 Source L.L.C. L00005384793 1 STOP COMMERCIAL KITCHEN EQUIPMENT, LLC L00005531370 1% for the Planet, Inc. N00005463860 1,000 Days N00004983554 1,000 DREAMS FUND N00005415959 10/40 CONNECTIONS, N00005517033 100 EYE STREET ACQUISITION LLC L00004191625 100 Fathers, The Inc. N00005501097 100 Property Partners of DC LLC L00005505861 100 REPORTERS N0000000904 1000 47th Pl NE LLC L00004651772 1000 CONNECTICUT MANAGER LLC L31372 1000 NEW JERSEY AVENUE, SE LLC L30799 1000 VERMONT AVENUE SPE LLC L36900 1001 17th Street NE L.L.C. L00005524805 1001 CONNECTICUT LLC L07124 1001 PENN LLC L38675 1002 3RD STREET, SE LLC L12518 1005 17th Street NE L.L.C. L00005524812 1005 E Street SE LLC L00004979576 1005 FIRST, LLC L00005478159 1005 Rhode Island Ave NE Partners LLC L00004843873 1006 Fairmont LLC L00005343026 1006 W St NW L.L.C. L00005517860 1009 NEW HAMPSHIRE LLC L04102 101 41ST STREET, NE LLC L23216 101 5TH ST, LLC L00005025803 101 GALVESTON PLACE SW LLC L51583 101 Geneva LLC L00005387687 101 P STREET, SW LLC L18921 101 PARK AVENUE PARTNERS, Inc. C00005014890 1010 25TH STREET LLC L52266 1010 IRVING, LLC L00004181875 1010 VERMONT AVENUE SPE LLC L36899 1010 WISCONSIN LLC L00005030877 1011 NEW HAMPSHIRE AVENUE LLC L17883 1012 13th St SE LLC L00005532833 1012 INC. -

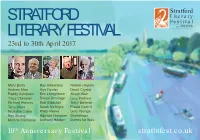

Strat-Lit-Fest-2017-Programme.Pdf

Stratford Literary STRATFORD Festival LITERARY FESTIVAL with 23rd to 30th April 2017 Mary Berry Roy Hattersley Natalie Haynes Andrew Marr Alys Fowler David Crystal Paddy Ashdown Ken Livingstone Alison Weir Tracy Chevalier Simon Armitage Lucy Parham Richard Holmes Rob Biddulph Tracy Borman Terry Waite Sarah McIntyre Planet Earth II Nicholas Crane Philip Reeve Gary Younge Roy Strong Horrible Histories Workshops Malorie Blackman Anthony Holden Events for Kids 10 th Anniversary Festival stratlitfest.co.uk BAILLIE GIFFORD LITERARY FESTIVAL SPONSORSHIP IMAGINATION, INSPIRATION AND A COMMITMENT TO THE FUTURE. Baillie Gifford is delighted to continue to sponsor some of the most renowned literary festivals throughout the UK. We believe that, much like a classic piece of literature, a great investment philosophy will stand the test of time. Baillie Gifford is one of the UK’s largest independent investment trust managers. In our daily work in investments we do our very best to emulate the imagination, insight and intelligence that successful writers bring to the creative process. In our own way we’re publishers too. Our free, award-winning Trust magazine provides you with an engaging and insightful overview of the investment world, along with details of our literary festival activity throughout AT BAILLIE GIFFORD WE the UK. BELIEVE IN THE VALUE OF GREAT LITERATURE 7RÛQGRXWPRUHRUWRWDNHRXWDIUHH AND IN LONG-STANDING subscription for Trust magazine, please call SUCCESS STORIES. us on 0800 280 2820 or visit us at www.bailliegifford.com/sponsorship Long-term investment partners Your call may be recorded for training or monitoring purposes. Baillie Gifford Savings Management Limited (BGSM) produces TrustNBHB[JOFBOEJTBOBGåMJBUFPG#BJMMJF(JGGPSE$P-JNJUFE XIJDIJTUIF manager and secretary of seven investment trusts.