Excerpt 9780801099755.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georg Friedrich Händel

GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL ~ ORATORIUM JOSHUA This live recording is part of a cycle of oratorios, masses and other grand works, performed in the basilica of Maulbronn Abbey under the direction of Jürgen Budday. The series combines authentically perfor- Die vorliegende Konzertaufnahme ist Teil eines Zyklus von Oratorien und med oratorios and masses with the optimal acoustics and atmosphere Messen, die Jürgen Budday im Rahmen der Klosterkonzerte Maulbronn über of this unique monastic church. This ideal location demands the trans- mehrere Jahre hinweg aufführte. Die Reihe verbindet Musik in historischer parency of playing and the interpretive unveiling of the rhetoric intima- Aufführungspraxis mit dem akustisch und atmosphärisch optimal geeigne- tions of the composition, which is especially aided by the historically ten Raum der einzigartigen Klosterkirche des Weltkulturerbes Kloster Maul- informed performance. The music is exclusively performed on recon- bronn. Dieser Idealort verlangt geradezu nach der Durchsichtigkeit des Mu- structed historical instruments, which are tuned to the pitch customary sizierens und der interpretatorischen Freilegung der rhetorischen Gestik der in the composer‘s lifetimes (this performance is tuned in a‘ = 415 Hz). Komposition, wie sie durch die historische Aufführungspraxis in besonderer Weise gewährleistet ist. So wird ausschließlich mit rekonstruierten histori- schen Instrumenten musiziert, die in den zu Lebzeiten der Komponisten üb- lichen Tonhöhen gestimmt sind (in dieser Aufführung a‘ = 415 Hz). FURTHER INFORMATION TO THIS PUBLICATION AND THE WHOLE CATALOGUE UNDER WWW.KUK-ART.COM Publishing Authentic Classical Concerts entails for us capturing and recording for posterity out- standing performances and concerts. The performers, audience, opus and room enter into an inti- mate dialogue that in its form and expression, its atmosphere, is unique and unrepeatable. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for Cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009

CORO CORO HANDEL: Coronation Anthems Winner of the Gramophone Award for cor16066 Best Baroque Vocal Album 2009 “Overall, this disc ranks as The Sixteen’s most exciting achievement in its impressive Handel discography.” HANDEL gramophone Choruses HANDEL: Dixit Dominus cor16076 STEFFANI: Stabat Mater The Sixteen adds to its stunning Handel collection with a new recording of Dixit Dominus set alongside a little-known treasure – Agostino Steffani’s Stabat Mater. THE HANDEL COLLECTION cor16080 Eight of The Sixteen’s celebrated Handel recordings in one stylish boxed set. The Sixteen To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit HARRY CHRISTOPHERS www.thesixteen.com cor16180 He is quite simply the master of chorus and on this compilation there is much rejoicing. Right from the outset, a chorus of Philistines revel in Awake the trumpet’s lofty sound to celebrate Dagon’s festival in Samson; the Israelites triumph in their victory over Goliath with great pageantry in How excellent Thy name from Saul and we can all feel the exuberance of I will sing unto the Lord from Israel in Egypt. There are, of course, two Handel oratorios where the choruses dominate – Messiah and Israel in Egypt – and we have given you a taster of pure majesty in the Amen chorus from Messiah as well as the Photograph: Marco Borggreve Marco Photograph: dramatic ferocity of He smote all the first-born of Egypt from Israel in Egypt. Handel is all about drama; even though he forsook opera for oratorio, his innate sense of the theatrical did not leave him. Just listen to the poignancy of the opening of Act 2 from Acis and Galatea where the chorus pronounce the gloomy prospect of the lovers and the impending appearance of the monster Polyphemus; and the torment which the Israelites create in O God, behold our sore distress when Jephtha commands them to “invoke the holy name of Israel’s God”– it’s surely one of his greatest fugal choruses. -

US Treasury Markets: Steps Toward Increased Resilience

U.S. Treasury Markets Steps Toward Increased Resilience DISCLAIMER This report is the product of the Group of Thirty’s Working Group on Treasury Market Liquidity and reflects broad agreement among its participants. This does not imply agreement with every specific observation or nuance. Members participated in their personal capacity, and their participation does not imply the support or agreement of their respective public or private institutions. The report does not represent the views of the membership of the Group of Thirty as a whole. ISBN 1-56708-184-3 How to cite this report: Group of Thirty Working Group on Treasury Market Liquidity. (2021). U.S. Treasury Markets: Steps Toward Increased Resilience. Group of Thirty. https://group30.org/publications/detail/4950. Copies of this paper are available for US$25 from: The Group of Thirty 1701 K Street, N.W., Suite 950 Washington, D.C. 20006 Telephone: (202) 331-2472 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.group30.org Twitter: @GroupofThirty U.S. Treasury Markets Steps Toward Increased Resilience Published by Group of Thirty Washington, D.C. July 2021 G30 Working Group on Treasury Market Liquidity CHAIR Timothy F. Geithner President, Warburg Pincus Former Secretary of the Treasury, United States PROJECT DIRECTOR Patrick Parkinson Senior Fellow, Bank Policy Institute PROJECT ADVISORS Darrell Duffie Jeremy Stein Adams Distinguished Professor of Management and Moise Y. Safra Professor of Economics, Professor of Finance, Stanford Graduate School of Harvard University Business WORKING GROUP MEMBERS William C. Dudley Masaaki Shirakawa Senior Research Scholar, Griswold Center for Economic Distinguished Guest Professor, Aoyama-Gakuin University Policy Studies at Princeton University Former Governor, Bank of Japan Former President, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Lawrence H. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXI, Number 3 Winter 2006 AMERICAN HANDEL SOCIETY- PRELIMINARY SCHEDULE (Paper titles and other details of program to be announced) Thursday, April 19, 2006 Check-in at Nassau Inn, Ten Palmer Square, Princeton, NJ (Check in time 3:00 PM) 6:00 PM Welcome Dinner Reception, Woolworth Center for Musical Studies Covent Garden before 1808, watercolor by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. 8:00 PM Concert: “Rule Britannia”: Richardson Auditorium in Alexander Hall SOME OVERLOOKED REFERENCES TO HANDEL Friday, April 20, 2006 In his book North Country Life in the Eighteenth Morning: Century: The North-East 1700-1750 (London: Oxford University Press, 1952), the historian Edward Hughes 8:45-9:15 AM: Breakfast, Lobby, Taplin Auditorium, quoted from the correspondence of the Ellison family of Hebburn Hall and the Cotesworth family of Gateshead Fine Hall Park1. These two families were based in Newcastle and related through the marriage of Henry Ellison (1699-1775) 9:15-12:00 AM:Paper Session 1, Taplin Auditorium, to Hannah Cotesworth in 1729. The Ellisons were also Fine Hall related to the Liddell family of Ravenscroft Castle near Durham through the marriage of Henry’s father Robert 12:00-1:30 AM: Lunch Break (restaurant list will be Ellison (1665-1726) to Elizabeth Liddell (d. 1750). Music provided) played an important role in all of these families, and since a number of the sons were trained at the Middle Temple and 12:15-1:15: Board Meeting, American Handel Society, other members of the families – including Elizabeth Liddell Prospect House Ellison in her widowhood – lived in London for various lengths of time, there are occasional references to musical Afternoon and Evening: activities in the capital. -

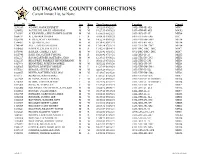

OUTAGAMIE COUNTY CORRECTIONS Current Inmate List, by Name

OUTAGAMIE COUNTY CORRECTIONS Current Inmate List, by Name InmateID Name Sex Race Time Incarcerated Location Classif 3281249 ADAMS, MARK EVERETT M B 08:32:00 09/22/21 JAIL-4TH-4E- 4E4 MIN7 3296692 AGUILLON, ANGEL ARMANDO M W 18:27:19 09/19/21 JAIL-4TH-4E- 4E5 MAX2 1739581 ALEXANDER, CHRISTOPHER JOSEPH M W 10:36:09 06/23/21 JAIL-3RD-3F- 3F MED4 1664771 ALI, ASSATA JAHINA F B 03:04:30 10/01/21 JAIL-5TH-5A- 5A6 REC 1020796 ALICEA, SCOTT ANTONIO M W 14:32:34 09/18/20 JAIL-5TH-5M- 5M8 MED4 1384437 ALQTAISHAT, ALI M W 10:19:45 09/12/21 JAIL-4TH-4A- 4A3 MED4 1749249 AULL, DAVID ANTHONY M W 15:42:24 05/21/21 JAIL-5TH-5M- 5M7 MED4 1029433 BARBER, CALVIN LEVELL M B 11:45:22 09/14/21 OUT-DRC-DRC- DRC MIN7 1070843 BASLER, GARRETT RAY M W 18:22:42 06/10/21 OUT-DRC-DRC- DRC MIN7 1036746 BASS, SYLVESTER TYRONE M B 10:20:43 07/28/21 JAIL-3RD-3I- 3I MED5 1033517 BAUMGARTNER, MATTHEW JOHN M W 13:38:18 08/06/21 JAIL-5TH-5N- 5N5 MED3 1511517 BEAUPREY, FORREST THUNDERHAWK M I 09:01:10 07/02/21 JAIL-5TH-5J- 5J6 MED4 1027811 BENAVIDEZ, RUBEN RAMIREZ M W 05:53:22 08/15/20 JAIL-3RD-3H- 3H MED4 1026305 BENTON, WINTER FORREST M I 11:27:48 01/19/21 JAIL-5TH-5M- 5M4 MED4 1575501 BESORE, STEVEN PHILLIP M W 04:08:29 08/21/21 JAIL-5TH-5J- 5J2 MED5 1029655 BEYER, MATTHEW WILLIAM M W 07:18:07 06/05/20 JAIL-5TH-5M- 5M4 MED3 117313 BIZARDIE, RAVEN MIAH F I 17:05:27 07/26/21 JAIL-5TH-5D- 5D5 MIN7 3237928 BLEVINS, ASHLEY MARIE F W 21:38:46 09/10/21 JAIL-5TH-5F- 5F DORM 1 MED4 1224808 BLOME, TAMARA MARIE F W 01:21:24 02/02/21 JAIL-5TH-5E- 5E DORM 3 MED4 1017460 BOAZ, AUTUMN -

1997 9520 00136 5511 4 Student Life

OLDEN •A1"* For Reference Not to be taken from this library CRANFORD PUBLIC LIBRARY NJ. 1997 9520 00136 5511 4 Student Life Clubs and 42 Activities 58 Academics ^Sports 70 102 People Senior 162 Portraits Cranford High School West End Place Cranford NJ, 07016 (908) 709-6272 Enrollment: 836 Volume 68 As we prepare to enter a new millennium, we dream of making a difference in the world. We imagine finding a cure for AIDS, saving the rainforests, exploring a new planet, or establishing peaceful interaction among all countries. Our goals are high; our dreams are big. Yet, we know that we possess the insight, ambition, and energy that is necessary to make the future a better and brighter place. For the time being, though, we imagine ourselves doing new and exciting things here at Cranford High School and in its surrounding community. Some of us imagine receiving an "A" on a Chemistry test, scoring a game-winning goal, earning our first paycheck, or getting our driver's license. Others imagine landing a role in the school musical, creating a beautiful piece of artwork, or voting for the first time. Whatever our interests may be, Cranford High School provides us with a vast array of classes, sports, and clubs to satisfy our quest for knowledge and our desire to be challenged. There is so much to experience at Cranford High, and with the resources for success at our fingertips, it is truly up to us to imagine the possibilities. Bv: Julie Schweitzer Above: ( HILD'S PLAY. Seniors Eric Messner, Brian Beirne, and Brent Heck are obviously young at heart. -

Rahab in the Book of Joshua and Other Texts of the Bible

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 3, Ver. II (Mar. 2014), PP 19-29 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Rahab in the Book of Joshua and other Texts of the Bible Obiorah Mary Jerome Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Abstract: Christian Sacred Scripture embodies some puzzling episodes which human minds can grasp only through similar faith that inspired its writers. The story of Rahah, presented as a prostitute in the Book of Joshua, provides such enigma. This woman rose from being a prostitute to a heroine for she was numbered among the Ancestresses of Jesus Christ. Her singular manifestation of faith in God and subsequent interpretations of this in the two parts of the Christian Bible are the focus of this paper. It is discovered that God’s ways are not our ways, for the Creator can choose anyone and at any time to accomplish his design. Keywords: Faith in God, Jericho, The Book of Joshua, Rahab, Spies I. INTRODUCTION At its face value the New Testament perspectives and interpretations of Rahab‟s story and personality as presented in the Book of Joshua appear surprising or even misapprehension of reality. She was a marginal woman with unusual character. In fact, the Hebrew version of Joshua 2 describes her as ‟iššāh zônāh – a professional secular prostitute distinct from qědēšāh – “sacred prostitute”; the latter would have been more respectful. It is instructive to observe that the texts of the New Testament and early Christian writers that appropriated the attitude of this woman towards the Israelite spies in projecting their theological thrusts preserve her Old Testament designation or identity when they still describe her as hē pornē “prostitute”. -

Handel Newsletter-2/2001 Pdf

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XV, Number 3 December 2000 MHF 2001 The 2001 Maryland Handel Festival & Conference marks the conclusion of the Festival’s twenty-year project of performing all Handel’s dramatic English oratorios in order of composition. With performances of THEODORA, May 4 and JEPHTHA, May 6 conducted by Paul Traver, we welcome back to the MHF stage soloists from previous seasons including: Linda Mabbs and Sherri Karam, soprano; Lorie Gratis and Leneida Crawford, mezzo-soprano; Derek Lee Ragin, countertenor; Charles Reid, tenor; Philip Collister, bass; with the Smithsonian Chamber Orchestra, Kenneth Slowik, Music Director; the University of Maryland Chorus, Edward Maclary, Music Director; and The Maryland Boys Choir, Joan Macfarland, director. As always, the American Handel Society and Maryland Handel Festival will join forces to present a scholarly conference, which this year brings together internationally renowned scholars from Canada, England, France, Germany, and the United States, and which will consist of four conference sessions devoted to various aspects of Handel studies today. Special events include the Howard Serwer Lecture (formerly the American Handel Society Lecture), to be presented on Saturday May 5 by the renowned HANDEL IN LONDON scholar Nicholas Temperley, the American Handel Society Dinner, later that same evening, and the pre- By 2002 there will be at least six different institutions concert lecture on Sunday May 6. in London involved with Handel: The conference and performances will take place in 1. British Library the new Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center at the University of Maryland; lodgings will once again be located at the Inn and Conference Center, University The British Library, holding the main collection of of Maryland University College, where the Society Handel autographs, is (together with the Royal dinner will also take place. -

Joshua Ronen Table of Contents • Education • Awards • Affiliations

Joshua Ronen Office: Stern School of Business New York University 44 West 4th Street New York, NY 10012 Tel: (212) 998-4144 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents • Education • Awards • Affiliations • Academic Positions • Other Positions • Books Published • Publications: Monographs • Publications: Articles • Publications: In the Professional and Popular Press • Publications: Book Review • Articles Reprinted • Public Appearances, Press Interviews, and Mentions in the Press • Other Professional Services • Special Editorial Work • Other Activities and Professional Contributions • Papers and Speeches Delivered Since 1972 • Working Papers • PhD Dissertations Supervised • Expert Testimony and Other Consulting Activities • Conferences Organized Education 1) PhD., Business Administration, Stanford University Palo Alto, California 1969. 2) Certificate, Financial Management, Stanford University (ICAME), Palo Alto, California, 1966-67. 3) M.S., Accounting, Hebrew University, Tel-Aviv, 1963. 4) B.A., Economics, Hebrew University, Tel-Aviv, 1959. Awards 1) Scholarly awards from the Hebrew University for high performance, 1958, 1964, and 1965. 2) Ford Foundation ICAME Fellowship to selected teachers of Business Management outside the U. S., 1966-67, 1967-68, and 1968-69. 3) Abacus award for the best paper in 2008, presented during the American Accounting Association Meetings on August 3, 2009. 4) Abacus award for the best manuscript in 2013, presented during the American Accounting Association Annual Conference ceremony on August 3, 2014. 5) -

A Filipino Resistance Reading of Joshua 1:1-9

International Voices in Biblical Studies A FILIPINO RESISTANCE READING OF JOSHUA 1:1–9 OF JOSHUA READING A FILIPINO RESISTANCE Lily Fetalsana-Apura uses contextual hermeneutics to offer an alternative interpretation of Joshua 1:1–9 that counters and resists historical-critical and theological readings legitimizing A Filipino Western conquests and imperialism. After outlining exegetical and hermeneutical procedures for contextual interpretation, she reads the Former Prophets in the context of four hundred years of colonial Resistance Reading of victimization and a continuing struggle against neocolonialism by marginalized and exploited communities such as those in the Philippines. She argues that Joshua 1:1–9 exhorts strength and courage against exploitation and domination by empire. Her work Joshua 1:1–9 subvert imperial ideology and that can serve as a model for other work inidentifies contextual themes hermeneutics and concepts of biblical in the texts. Deuteronomistic History that is an assistant professor in the Silliman studiesLILY FETALSANA-APURA courses. University Divinity School in the Philippines. She teaches biblical FETALSANA-APURA Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-333-8) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Lily Fetalsana-Apura A FILIPINO RESISTANCE READING OF JOSHUA 1:1–9 INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 9 A FILIPINO RESISTANCE READING OF JOSHUA 1:1–9 by Lily Fetalsana-Apura Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by Lily Fetalsana-Apura All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher.