From Servitude to Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Jullundur, Part X-A & B

,CENSUS 1971 PARTS X-A" II VILLAGE & TOWN SERIES 17 DIRECTORY PUNJAB VILLAGE & TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENS'US ABSTRACT DISTRICT JULLUN'DUR CENSUS DISTRICT HANDBOOK P. L. SONDHI H. S. KWATRA ". OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE OF THE PfJ'NJAB CIVIL SERVIce Ex-officio Director of Census OperatiONl Deputy Director (~l Cpnsus Operations ', .. PUNJAB PUNJAB' Modf:- Julluodur - made Sports Goods For 01 ympics ·-1976 llvckey al fhe Montreal Olympics. 1976, will be played with halls manufactured in at Jullundur. Jullundur has nearly 350 sports goods 111l1nl~ractur;l1g units of various sizes. These small units eXJlort tennis and badminton rackets, shuttlecocks and several types of balls including cricket balls. Tlte nucleu.s (~( this industry was formed h,J/ skilled and semi-skilled workers who came to 1ndia a/It?r Partition. Since they could not afford 10 go far away and were lodged in the two refugee can'lps located on the outskirts of .IuJ/undur city in an underdeveloped area, the availabi lity of the sk illed work crs attracted the sport,\' goods I1zCllllljacturers especiallY.from Sialkot which ,was the centre (~f sports hJdustry heji,)re Partition. Over 2,000 people are tU preSt'nt employed in this industry. Started /roln scratch after ,Partilion, the indLlstry now exports goods worth nearly Rs. 5 crore per year to tire Asian and European ("'omnu)fzwealth countril's, the lasl being our higgest ilnporters. Alot(( by :-- 1. S. Gin 1 PUNJAB DISTRICT JULLUNDUR kflOMlTR£S 5 0 5 12_ Ie 20 , .. ,::::::;=::::::::;::::_:::.:::~r::::_ 4SN .- .., I ... 0 ~ 8 12 MtLEI "'5 H s / I 30 3~, c ! I I I I ! JULLUNOUR I (t CITY '" I :lI:'" I ,~ VI .1 ..,[-<1 j ~l~ ~, oj .'1 i ;;1 ~ "(,. -

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr Ative Detail of Repair Approval Name of Name Xen/Mobile No

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr ative Detail of Repair Approval Name of Name Xen/Mobile No. Sr. No. Distt. MC Name of Work Strengthe Premix Contractor/Agency Name of SDO/Mobile No. Length Cost Raising ning Carepet in in Km. in lacs in Km in Km Km 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 PARTAPPURA TO DERA SEN BHAGAT M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 1 Jalandhar Bilga 2.4 15.06 0 0 2.4 (16 ft wide) (1.50 km length) Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 MAO SAHIB TO DHUSI BANDH (KHERA M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 2 Jalandhar Bilga 4.24 40.31 0 2.44 4.24 BET)VIA KULIAN TEHAL SINGH Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 MAU SAHIB TO RURKA KALAN VIA M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 3 Jalandhar Bilga PARTABPURA MEHSAMPUR (13.15= 21.04 128.57 0.31 0.82 21.04 Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 16' wide) PHIRNI PIND MAOSAHIB TO MAOSAHIB M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 4 Jalandhar Bilga 0.8 7.75 0 0.435 0.8 DHUSI BAND ROAD Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 PHILLAUR RURKA KALAN TO RURKA Sh. Rakesh Kumar Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 5 Jalandhar Bilga 3.35 31.06 0 1.805 3.35 KALAN MAU SAHIB ROAD Contractor Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 PHILLAUR NURMAHAL ROAD TO Sh. Rakesh Kumar Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 6 Jalandhar Bilga 3.1 24.27 0 1.015 3.1 PRATABPURA VIA SANGATPUR Contractor Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 Sh. -

Administrative Atlas , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 PUNJAB ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS f~.·~'\"'~ " ~ ..... ~ ~ - +, ~... 1/, 0\ \ ~ PE OPLE ORIENTED DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB , The maps included in this publication are based upon SUNey of India map with the permission of the SUNeyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified. The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 03-010-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71. Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published. -

Pincode Officename Statename Minisectt Ropar S.O Thermal Plant

pincode officename districtname statename 140001 Minisectt Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Thermal Plant Colony Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Ropar H.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Morinda S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140101 Bhamnara B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Rattangarh Ii B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Saheri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Dhangrali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Tajpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Lutheri S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Rollumajra B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Kainaur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Makrauna Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Samana Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Barsalpur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Chaklan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Dumna B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140103 Kurali S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Allahpur B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Burmajra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Chintgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Dhanauri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Jhingran Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Kalewal B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Kaishanpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Mundhon Kalan B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sihon Majra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Singhpura B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sotal B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Sahauran B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140108 Mian Pur S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Pathreri Jattan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Rangilpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Sainfalpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Singh Bhagwantpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Kotla Nihang B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140108 Behrampur Zimidari B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Ballamgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Purkhali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140109 Khizrabad West S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140109 Kubaheri B.O Mohali PUNJAB -

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads - A Literature Review Anita Sharma CREATE PATHWAYS TO ACCESS Research Monograph No. 58 January 2011 University of Sussex Centre for International Education The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter- generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The lead partner of CREATE is the Centre for International Education at the University of Sussex. The partners are: -

Institute Wise Intake.Pdf

1 CONTENTS Chapter No. DESCRIPTIONS Page No. ABBREVIATIONS AND TERMS USED 1 1 POLYTECHNIC EDUCATION-AN OVERVIEW 2 2 IMPORTANT INFORMATION 3-7 ELIGIBILITY FOR ALL DIPLOMA COURSES 8-17 A ADMISSION IN DIPLOMA ENGG. 8-12 3 B ADMISSION IN DIPLOMA ENGG. LATERAL ENTRY 13-15 C ADMISSION IN DIPLOMA PHARMACY 16-17 D PHYSICAL STANDARDS FOR ALL DIPLOMA COURSES 17 4 RESERVATION OF SEATS AND SPECIAL QUOTA SEATS 18-22 PROCEDURE FOR APPLYING ONLINE FOR ALL DIPLOMA COURSES 23 A INSTRUCTIONS FOR APPLYING ONLINE 23-24 B PROCEDURE FOR ONLINE REGISTRATION 24 C INSTRUCTIONS FOR DEPOSIT OF APPLICATION FEE OR ENTRANCE TEST FEE 25 5 INSTRUCTIONS FOR VERIFICAITON & CONFIRMATION OF ONLINE FILLED APPLICATION D 25-26 FORM (For Diploma Engg., Diploma Pharmacy and Diploma Engg. Lateral Entry) E ADMIT CARD FOR ONLINE LATERAL ENTRY DIPLOMA ENTRANCE TEST i.e. DET (L)-2019 26 F INSTRUCTIONS FOR DET (L)-2019 26 G RESULT OF DET (L)-2019 26 6 COUNSELING PROCEDURE FOR ALL DIPLOMA COURSES 27-30 7 REPORTING OF THE CANDIDATE AT ALLOTTED INSTITUTE 31-33 8 VARIOUS FINANCIAL SUPPORTS AND MOTIVATIONAL SCHEMES 34-35 9 INFORMATION REGARDING FEE AND REFUND OF FEE 36 10 POST ADMISSION INSTRUCTIONS & RULES 37-39 APPENDIX I TO IX I KEY DATES (Admission Schedule of Diploma Courses for the session 2019-20) 40-43 II LIST OF DESIGNATED CENTERS FOR VERIFICAITON OF ONLINE FILLED APPLICATION FORMS 44-45 III LIST OF EXAMINATION CENTERS FOR CONDUCT OF ON-LINE DET (L)-2019 46 IV INSTITUTIONS LIST ALONG WITH DISCIPLINE & SANCTIONED INTAKE FOR THE SESSION 2019-20 47-54 V INSTITUTE WISE FEE STRUCTURE 55-66 VI INSTITUTE WISE RESULT FOR MAY-JUNE 2018 67-72 VII ATTENDANCE AND LEAVE RULES 73 ANNEXURES I TO XX 74-95 2 ABBREVIATIONS AND TERMS USED i. -

Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 16 December 2019

United Nations E/CN.6/2020/NGO/201 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 16 December 2019 English only Commission on the Status of Women Sixty-fourth session 9–20 March 2020 Follow-up to the Fourth World Conference on Women and to the twenty-third special session of the General Assembly entitled “Women 2000: gender equality, development and peace for the twenty-first century” Statement submitted by The Sant Nirankari Mandal, Delhi, a non-governmental organization in consultative status with the Economic and Social Council* The Secretary-General has received the following statement, which is being circulated in accordance with paragraphs 36 and 37 of Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. * The present statement is issued without formal editing. 19-21767 (E) 171219 *1921767* E/CN.6/2020/NGO/201 Statement Spiritual awakening rules out gender discrimination Sant Nirankari Mandal, Delhi heartily thanks the NGO Committee on the Status of Women for a friendly mail, seeking a written statement on the thematic issues considered by the Commission on the Status of Women in accordance with Security Council Resolutions 1996/31. Decidedly, the United Nations Economic and Social Council is earnestly paying the attention that this matter deserves. It is worthwhile mentioning that Sant Nirankari Mandal, Delhi was granted special consultative status by the United Nations in 2012 and considering its performance, the status was reclassified as general consultative status in 2018. Ever since, we have been submitting written statements on the given subjects and getting opportunities for our delegates to participate every year at the United Nations Headquarters, New York. -

Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CASTE, KINSHIP AND SEX RATIOS IN INDIA Tanika Chakraborty Sukkoo Kim Working Paper 13828 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13828 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2008 We thank Bob Pollak, Karen Norberg, David Rudner and seminar participants at the Work, Family and Public Policy workshop at Washington University for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Lauren Matsunaga and Michael Scarpati for research assistance and Cassie Adcock and the staff of the South Asia Library at the University of Chicago for their generous assistance in data collection. We are also grateful to the Weidenbaum Center and Washington University (Faculty Research Grant) for research support. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim NBER Working Paper No. 13828 March 2008 JEL No. J12,N35,O17 ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between kinship institutions and sex ratios in India at the turn of the twentieth century. Since kinship rules varied by caste, language, religion and region, we construct sex-ratios by these categories at the district-level using data from the 1901 Census of India for Punjab (North), Bengal (East) and Madras (South). -

Changing Caste Relations and Emerging Contestations in Punjab

CHANGING CASTE RELATIONS AND EMERGING CONTESTATIONS IN PUNJAB PARAMJIT S. JUDGE When scholars and political leaders characterised Indian society as unity in diversity, there were simultaneous efforts in imagining India as a civilisational unity also. The consequences of this ‘imagination’ are before us in the form of the emergence of religious nationalism that ultimately culminated into the partition of the country. Why have I started my discussion with the issue of religious nationalism and partition? The reason is simple. Once we assume that a society like India could be characterised in terms of one caste hierarchical system, we are essentially constructing the discourse of dominant Hindu civilisational unity. Unlike class and gender hierarchies which are exist on economic and sexual bases respectively, all castes cannot be aggregated and arranged in hierarchy along one axis. Any attempt at doing so would amount to the construction of India as essentially the Hindu India. Added to this issue is the second dimension of hierarchy, which could be seen by separating Varna from caste. Srinivas (1977) points out that Varna is fixed, whereas caste is dynamic. Numerous castes comprise each Varna, the exception to which is the Brahmin caste whose caste differences remain within the caste and are unknown to others. We hardly know how to distinguish among different castes of Brahmins, because there is complete absence of knowledge about various castes among them. On the other hand, there is detailed information available about all the scheduled castes and backward classes. In other words, knowledge about castes and their place in the stratification system is pre- determined by the enumerating agency. -

Page11local.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU MONDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2016 (PAGE 11) BJP-PDP losing in their Manhas inaugurates medical camp Khajuria inaugurates bathrooms Excelsior Correspondent Organization. The camp was innagurated constituencies: Bhalla JAMMU, Feb 28: by Member of Parliament Rajya in Mouni Maharaj Ashram Highlighting various Health Excelsior Correspondent strong disapproval of the ‘agen- Sabha, Shamsher Singh Manhas Excelsior Correspondent which themselves are the sym- Schemes for people of India, alongwith MLA Bali Bhagat, bols of civilization, culture and da of alliance’ which offered JAMMU, Feb 28: Former JAMMU, Feb 28: Former Member Parliament (Rajya WWAO National Advisor Veena communal harmony. nothing to the people except a State president BJP & MLC minister and senior Congress Sabha) Shamsher Singh Manhas Handa renowned educationalist He expressed hope that the power sharing formula to the Ashok Khajuria, along with leader Raman Bhalla today said said healthy people will make and Social Activist were also Ashram Management will keep coalition partners. Mouni Maharaj Ashram that both BJP and PDP are los- India strong to become powerful present on the occasion. these bathrooms and toilets He said that the people of Management President Neeraj ing their ground in their respec- nation of world. After the completion of pro- Jammu region were feeling While inaugurating medical tive constituencies and now gramme Sarla Kohli presented cheated and betrayed as none of camp at Paloura, Manhas said stand exposed before the people. memento to the MLA Bali the pre-poll pledges by the BJP NDA Government led by Prime Bhagat and Veena Handa pre- MLA Sat Sharma during birthday celebration of Shri Guru Minister Narendra Modi is com- Ravi Dass Ji. -

2. Pseudo Gurus in Sikhism

Pseudo Gurus in Sikhism with their living and non-living gurus. Present living Sikh religion right from its guru of this sect is Baba Udai Singh with their head inception is facing threat from self quarter at Bhaini Sahib, at Ludhiana Punjab. Very proclaimed gods and gurus. rarely or occasionally, Namdharis go to the Sikh Dissensions in the early Sikh Panth Gurdwaras, as they have built their own. Also, perhaps took the shape of several minor or Ram Singh has prescribed a standardised code major sects during the16th and the 17th centuries. Incidently, (Rahitnama) for them with Namdhari version of Ardas these first and the most serious early challenges to the (prayer). Although believing in the tenets of Guru newly evolving Sikh faith and its identity were posed by Granth Sahib, Akal Takhat has declared them non- the progeny or the direct descendants of the Sikh Sikhs. Gurus. These persons asserted their claims in the form Another sect which has harmed Sikh religion of a dissent to grab the fundamental institutions of most is Pseudo (Sant) Nirankaris of Delhi. This mission Guruship and the bani or the Adi-Granth, sacred bifurcated from Nirankaris, who originated in scripture of the Sikhs. B h a iW Jithasw theant riseSin ghof Kthesehalra peripheral or centrifugal forces, the Mughal state felt Rawalpindi in the northwest of the Punjab (Now encouraged to enhance its opposition in more ways Pakistan). The sect was founded by a Sahajdhari Sikh than one. Conservative Hindu elements did not lag Baba Dyal (1785-1855), a bullion merchant. This behind to play their role. -

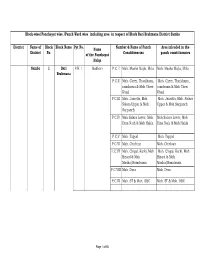

Block-Wise/Panchayat Wise /Panch Ward Wise Including Area in Respect of Block Bari Brahmana District Samba

Block-wise/Panchayat wise /Panch Ward wise including area in respect of Block Bari Brahmana District Samba District Name of Block Block Name Pyt No. Name Number & Name of Panch Area inlcuded in the District No. of the Panchayat Constituencies panch constituencies Halqa Samba 1 Bari P.H. 1 Badhori P.C. I Moh. Masha Majla, Mela Moh. Masha Majla, Mela Brahmana P.C.II Moh. Cheer, Tharkhana, Moh. Cheer, Tharkhana, ramdassia & Moh Cheer ramdassia & Moh Cheer Khad Khad P.C.III Moh. Jasrotia, Moh. Moh. Jasrotia, Moh. Salara Salara Upper & Moh Upper & Moh Sarpanch Sarpanch P.C.IV Moh Salara Lower, Moh. Moh Salara Lower, Moh. Dina Nath & Moh Hakla Dina Nath & Moh Hakla P.C.V Moh. Tapyal Moh. Tapyal P.C.VI Moh. Chichian Moh. Chichian P.C.VII Moh. Chigal, Karki, Moh Moh. Chigal, Karki, Moh Bizard & Moh. Bizard & Moh. Masha/Ramdassia Masha/Ramdassia P.C.VIII Moh. Dera Moh. Dera P.C.IX Moh. ST & Moh. OBC Moh. ST & Moh. OBC Page 1 of 58 District Name of Block Block Name Pyt No. Name Number & Name of Panch Area inlcuded in the District No. of the Panchayat Constituencies panch constituencies Halqa P.C. I Khiddia Khiddia P.C.II Moh. Masha & Moh. Baj Moh. Masha & Moh. Baj Singh Singh P.C.III Moh Khatana, Moh. Moh Khatana, Moh. Hakla , Hakla , Moh Masha & Moh Masha & Moh. Moh. Bhagata Bhagata P.C.IV Moh. Khepar. Bilal, Moh. Khepar. Bilal, Chichian Chichian P.C.V Moh. Chard Moh. Chard P.H. 2 Bari P.C.VI Moh. Maj.