Martial Races' and War Time Unit Deployment in the Indian Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life-Members

Life Members SUPREME COURT BAR ASSOCIATION Name & Address Name & Address 1 Abdul Mashkoor Khan 4 Adhimoolam,Venkataraman Membership no: A-00248 Membership no: A-00456 Res: Apartment No.202, Tower No.4,, SCBA Noida Res: "Prashanth", D-17, G.K. Enclave-I, New Delhi Project Complex, Sector - 99,, Noida 201303 110048 Tel: 09810857589 Tel: 011-26241780,41630065 Res: 328,Khan Medical Complex,Khair Nagar Fax: 41630065 Gate,Meerut,250002 Off: D-17, G.K. Enclave-I, New Delhi 110048 Tel: 0120-2423711 Tel: 011-26241780,41630065 Off: Apartment No.202, Tower No.4,, SCBA Noida Ch: 104,Lawyers Chamber, A.K.Sen Block, Supreme Project Complex, Sector - 99,, Noida 201303 Court of India, New Delhi 110001 Tel: 09810857589 Mobile: 9958922622 Mobile: 09412831926 Email: [email protected] 2 Abhay Kumar 5 Aditya Kumar Membership no: A-00530 Membership no: A-00412 Res: H.No.1/12, III Floor,, Roop Nagar,, Delhi Res: C-180,, Defence Colony, New Delhi 110024 110007 Off: C-13, LGF, Jungpura, New Delhi 110014 Tel: 24330307,24330308 41552772,65056036 Tel: 011-24372882 Tel: 095,Lawyers Chamber, Supreme Court of India, Ch: 104, Lawyers Chamber, Supreme Court of India, Ch: New Delhi 110001 New Delhi 110001 23782257 Mobile: 09810254016,09310254016 Tel: Mobile: 9911260001 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 3 Abhigya 6 Aganpal,Pooja (Mrs.) Membership no: A-00448 Membership no: A-00422 Res: D-228, Nirman Vihar, Vikas Marg, Delhi 110092 Res: 4/401, Aganpal Chowk, Mehrauli, New Delhi Tel: 22432839 110030 Off: 704,Lawyers Chamber, Western Wing, Tis Hazari -

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

1: Scope and Important of Urdu: Urdu Is a Standardized Register of the Hindustani Language It Is the National Language and Ling

1: Scope And Important Of Urdu: Urdu Is A Standardized Register Of The Hindustani Language It Is The National Language And Lingua Franca Of Pakistan, And An Official Language Of Six States Of India. It Is Also One Of The 22 Official Languages Recognized In The Constitution Of India. Urdu Is Historically Associated With The Muslims Of The Northern Indian Subcontinent. Apart From Specialized Vocabulary, Urdu Is Mutually Intelligible With Standard Hindi, Another Recognized Register Of Hindustani. The Urdu Variant Received Recognition And Patronage Under British Rule When The British Replaced The Persian And Local Official Languages With The Urdu And English Languages In The North Indian Regions Of Jammu and Kashmir In 1846 And Punjab In 1849. Urdu, Like Hindi, Is A Form Of Hindustani. It Evolved From The Medieval (6th To 13th Century) Apabhraṃśa Register Of The Preceding Shauraseni Language, A Middle Indo-Aryan Language That Is Also The Ancestor Of Other Modern Languages, Including The Punjabi Dialects. Urdu Developed Under The Influence Of The Persian And Arabic Languages, Both Of Which Have Contributed A Significant Amount Of Vocabulary To Formal Speech around 99% Of Urdu Verbs Have Their Roots In Sanskrit And Prakrit. Although The Word Urdu Itself Is Derived From The Turkic Word Ordu Or Orda, From Which English Horde Is Also Derived, Turkic Borrowings In Urdu Are Minimal And Urdu Is Not Genetically Related To The Turkic Languages. Urdu Words Originating From Chagatai And Arabic Were Borrowed Through Persian And Hence Are Personalized Versions Of The Original Words. For Instance, The Arabic Ta' Marbuta Changes To He Or Te . -

ON DOCTORS and BOMBS Supermarkets Being Brought in to Colonise ESSAY As We Take a Step Back from the Events of the Primary Care

BaTHcE k Pages Contents Viewpoint 840 ON DOCTORS AND BOMBS supermarkets being brought in to colonise ESSAY As we take a step back from the events of the primary care. Management speak dominates The 21st century GP: summer, perhaps now it is possible to look the discourse, divide-and-rule is the modus physician and priest? Jim Pink, Lionel Jacobson rationally at the effects of the alleged terrorist operandi and drug company research rules and Mike Pritchard attacks in Glasgow and London on the the roost. League tables and other punitive medical profession in this country. measures are manifestations of the 842 Firstly, we need to recognise that the issues pathological culture of bullying and EDO Michael Lasserson are those of criminality and global politics and intimidation that defines transnational are in no way medico-legal or related to capitalist structures. Many diseases of 843 overseas recruitment procedures. We must affluence are actually diseases of ESSAY not succumb to the blind panic that overtook corporatism. From a non-patient’s perspective government and regulatory bodies following A few weeks ago, a colleague of mine in Peter Tomson the Shipman revelations. As a consequence Glasgow was stabbed in the middle of her of this ethos, a lawyer specialising in medical morning surgery. Are we now going to 844 negligence was put in charge of the suspect all patients and install CCTV in our REPORTAGE investigation and with stunning intellectual waiting and consulting-rooms? No, of course The 61st Edinburgh International Film Festival laziness, promptly succeeded in conflating not. Bad eggs do bad things, whether they David Watson criminality with competence issues. -

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

GIPE-010149.Pdf

THE PRINCES OF INDIA [By permission of the Jlidor;a f- Albert 1lluseum THE CORONAT I O); OF AN Ii:\DI AN SOVE R E I G:\f From the :\janta Frescoes THE PRINCES OF INDIA WITH A CHAPTER ON NEPAL By SIR \VILLIAM BAR TON K.C.I.E., C.S.I. With an Introduction by VISCOUNT HAL IF AX K.G., G.C.S.l. LONDON NISBET & CO. LTD. 11 BER!'\ERS STllEET, 'W.I TO ~IY '\'!FE JJ!l.il ul Prir.:d i11 Grt~ Eri:Jill liy E11.u::, Wa:.:ctl 6- riney, W., L~ ad A>:esbury Firs! p.,.;::isilll ;,. 1;34 INTRODUCTION ITHOUT of necessity subscribing to everything that this book contains, I W am very glad to accept Sir William Barton's invitation to write a foreword to this con .. tribution to our knowledge of a subject at present occupying so large a share of the political stage. Opinion differs widely upon many of the issues raised, and upon the best way of dealing with them. But there will be no unwillingness in any quarter to admit that in the months to come the future of India will present to the people of this country the most difficult task in practical statesmanship with which thet 1hive ever been confronted. If the decision is to be a wise one it must rest upon a sound conception of the problem itself, and in that problem the place that is to be taken in the new India by the Indian States is an essential factor. Should they join the rest of India in a Federation ? Would they bring strength to a Federal Government, or weakness? Are their interests compatible with adhesion to an All-India v Vl INTRODUCTION Federation? What should be the range of the Federal Government's jurisdiction over them? These are some of the questions upon which keen debate will shortly arise. -

Divide and Conquer

ISSN 1936-5349 (print) ISSN 1936-5357 (online) HARVARD JOHN M. OLIN CENTER FOR LAW, ECONOMICS, AND BUSINESS DIVIDE AND CONQUER Eric A. Posner, Kathryn Spier, & Adrian Vermeule Discussion Paper No. 639 5/2009 Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 This paper can be downloaded without charge from: The Harvard John M. Olin Discussion Paper Series: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/ The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1349971 Divide and Conquer Eric A. Posner,* Kathryn Spier,** & Adrian Vermeule*** Abstract: The maxim “divide and conquer” (divide et impera) is invoked frequently in law, history, and politics, but often in a loose or undertheorized way. We suggest that the maxim is a placeholder for a complex of ideas related by a family resemblance, but differing in their details, mechanisms and implications. We provide an analytic taxonomy of divide and conquer mechanisms in the settings of a Stag Hunt Game and an indefinitely-repeated Prisoners’ Dilemma. A number of applications are considered, including labor law, bankruptcy, constitutional design and the separation of powers, imperialism and race relations, international law, litigation and settlement, and antitrust law. Conditions under which divide and conquer strategies reduce or enhance social welfare, and techniques that policy makers can use to combat divide and conquer tactics, are also discussed. JEL: K0 * University of Chicago Law School. ** Harvard Law School. *** Harvard Law School. Thanks to Adam Badawi, Anu Bradford, Jim Dana, Mary Anne Franks, Aziz Huq, Claudia Landeo, Jonathan Masur, Madhavi Sunder, Lior Strahilevitz, and an audience at the University of Chicago Law School for valuable comments, and Paul Mysliwiec and Colleen Roh for helpful research assistance. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

Pakistan S Strategic Blunder at Kargil, by Brig Gurmeet

Pakistan’s Strategic Blunder at Kargil Gurmeet Kanwal Cause of Conflict: Failure of 10 Years of Proxy War India’s territorial integrity had not been threatened seriously since the 1971 War as it was threatened by Pakistan’s ill-conceived military adventure across the Line of Control (LoC) into the Kargil district of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) in the summer months of 1999. By infiltrating its army soldiers in civilian clothes across the LoC, to physically occupy ground on the Indian side, Pakistan added a new dimension to its 10-year-old ‘proxy war’ against India. Pakistan’s provocative action compelled India to launch a firm but measured and restrained military operation to clear the intruders. Operation ‘Vijay’, finely calibrated to limit military action to the Indian side of the LoC, included air strikes from fighter-ground attack (FGA) aircraft and attack helicopters. Even as the Indian Army and the Indian Air Force (IAF) employed their synergised combat potential to eliminate the intruders and regain the territory occupied by them, the government kept all channels of communication open with Pakistan to ensure that the intrusions were vacated quickly and Pakistan’s military adventurism was not allowed to escalate into a larger conflict. On July 26, 1999, the last of the Pakistani intruders was successfully evicted. Why did Pakistan undertake a military operation that was foredoomed to failure? Clearly, the Pakistani military establishment was becoming increasingly frustrated with India’s success in containing the militancy in J&K to within manageable limits and saw in the Kashmiri people’s open expression of their preference for returning to normal life, the evaporation of all their hopes and desires to bleed India through a strategy of “a thousand cuts”. -

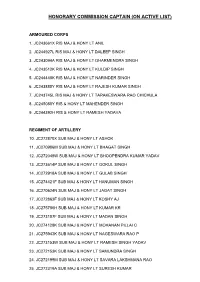

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

The Gurkhas', 1857-2009

"Bravest of the Brave": The making and re-making of 'the Gurkhas', 1857-2009 Gavin Rand University of Greenwich Thanks: Matthew, audience… Many of you, I am sure, will be familiar with the image of the ‘martial Gurkha’. The image dates from nineteenth century India, and though the suggestion that the Nepalese are inherently martial appears dubious, images of ‘warlike Gurkhas’ continue to circulate in contemporary discourse. Only last week, Dipprasad Pun, of the Royal Gurkha Rifles, was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross for single-handedly fighting off up to 30 Taliban insurgents. In 2010, reports surfaced that an (unnamed) Gurkha had been reprimanded for using his ‘traditional’ kukri knife to behead a Taliban insurgent, an act which prompted the Daily Mail to exclaim ‘Thank god they’re on our side!) Thus, the bravery and the brutality of the Gurkhas – two staple elements of nineteenth century representations – continue to be replayed. Such images have also been mobilised in other contexts. On 4 November 2008, Chief Superintendent Kevin Hurley, of the Metropolitan Police, told the Commons’ Home Affairs Select Committee, that Gurkhas would make excellent ‘recruits’ to the capital’s police service. Describing the British Army’s Nepalese veterans as loyal, disciplined, hardworking and brave, Hurley reported that the Met’s senior commanders believed that ex-Gurkhas could provide a valuable resource to London’s police. Many Gurkhas, it was noted, were multilingual (in subcontinental languages, useful for policing the capital’s diverse population), fearless (and therefore unlikely to be intimidated by the apparently rising tide of knife and gun crime) and, Hurley noted, the recruiting of these ‘loyal’, ‘brave’ and ‘disciplined’ Nepalese would also provide an excellent (and, one is tempted to add, convenient) means of diversifying the workforce. -

“Othering” Oneself: European Civilian Casualties and Representations of Gendered, Religious, and Racial Ideology During the Indian Rebellion of 1857

“OTHERING” ONESELF: EUROPEAN CIVILIAN CASUALTIES AND REPRESENTATIONS OF GENDERED, RELIGIOUS, AND RACIAL IDEOLOGY DURING THE INDIAN REBELLION OF 1857 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences Florida Gulf Coast University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree of Masters of Arts in History By Stefanie A. Babb 2014 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in History ________________________________________ Stefanie A. Babb Approved: April 2014 _________________________________________ Eric A. Strahorn, Ph.D. Committee Chair / Advisor __________________________________________ Frances Davey, Ph.D __________________________________________ Habtamu Tegegne, Ph.D. The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Copyright © 2014 by Stefanie Babb All rights reserved One must claim the right and the duty of imagining the future, instead of accepting it. —Eduardo Galeano iv CONTENTS PREFACE v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE HISTORIOGRAPHY 12 CHAPTER TWO LET THE “OTHERING” BEGIN 35 Modes of Isolation 39 Colonial Thought 40 Racialization 45 Social Reforms 51 Political Policies 61 Conclusion 65 CHAPTER THREE LINES DRAWN 70 Outbreak at Meerut and the Siege on Delhi 70 The Cawnpore Massacres 78 Changeable Realities 93 Conclusion 100 CONCLUSION 102 APPENDIX A MAPS 108 APPENDIX B TIMELINE OF INDIAN REBELLION 112 BIBLIOGRAPHY 114 v Preface This thesis began as a seminar paper that was written in conjunction with the International Civilians in Warfare Conference hosted by Florida Gulf Coast University, February, 2012.