Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rock Stratigraphy of the Silurian System in Northeastern and Northwestern Illinois

2UJ?. *& "1 479 S 14.GS: CIR479 STATE OF ILLINOIS c. 1 DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION Rock Stratigraphy of the Silurian System in Northeastern and Northwestern Illinois H. B. Willman GEOLOGICAL ILLINOIS ""SURVEY * 10RM* APR 3H986 ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY John C. Frye, Chief Urbano, IL 61801 CIRCULAR 479 1973 CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Time-stratigraphic classification 3 Alexandrian Series 5 Niagaran Series 5 Cayugan Series 6 Regional correlations 6 Northeastern Illinois 6 Development of the classification 9 Wilhelmi Formation 12 Schweizer Member 13 Birds Member 13 Elwood Formation 14 Kankakee Formation 15 Drummond Member 17 Offerman Member 17 Troutman Member 18 Plaines Member 18 Joliet Formation 19 Brandon Bridge Member 20 Markgraf Member 21 Romeo Member 22 Sugar Run Formation . „ 22 Racine Formation 24 Northwestern Illinois 26 Development of the classification 29 Mosalem Formation 31 Tete des Morts Formation 33 Blanding Formation 35 Sweeney Formation 36 Marcus Formation 3 7 Racine Formation 39 References 40 GEOLOGIC SECTIONS Northeastern Illinois 45 Northwestern Illinois 52 FIGURES Figure 1 - Distribution of Silurian rocks in Illinois 2 2 - Classification of Silurian rocks in northeastern and northwestern Illinois 4 3 - Correlation of the Silurian formations in Illinois and adjacent states 7 - CM 4 Distribution of Silurian rocks in northeastern Illinois (modified from State Geologic Map) 8 - lis. 5 Silurian strata in northeastern Illinois 10 ^- 6 - Development of the classification of the Silurian System in |§ northeastern Illinois 11 7 - Distribution of Silurian rocks in northwestern Illinois (modified ;0 from State Geologic Map) 2 7 8 - Silurian strata in northwestern Illinois 28 o 9 - Development of the classification of the Silurian System in CO northwestern Illinois 30 10 - Index to stratigraphic units described in the geologic sections • • 46 ROCK STRATIGRAPHY OF THE SILURIAN SYSTEM IN NORTHEASTERN AND NORTHWESTERN ILLINOIS H. -

Columnals (PDF)

2248 22482 2 4 V. INDEX OF COLUMNALS 8 Remarks: In this section the stratigraphic range given under the genus is the compiled range of all named species based solely on columnals assigned to the genus. It should be noted that this range may and often differs considerably from the range given under the same genus in Section I, because that range is based on species identified on cups or crowns. All other abbreviations and format follow that of Section I. Generic names followed by the type species are based on columnals. Genera, not followed by the type species, are based on cups and crowns as given in Section I. There are a number of unlisted columnal taxa from the literature that are indexed as genera recognized on cups and crowns. Bassler and Moodey (1943) did not index columnal taxa that were not new names or identified genera with the species unnamed. I have included some of the omissions of Bassler and Moodey, but have not made a search of the extensive literature specifically for the omitted citations because of time constraints. Many of these unlisted taxa are illustrated in the early state surveys of the eastern and central United States. Many of the columnal species assigned to genera based on cups or crowns are incorrect assignments. An uncertain, but significant, number of the columnal genera are synonyms of other columnal genera as they are based on different parts of the stem of a single taxon. Also a number of the columnal genera are synonyms of genera based on cups and crowns as they come from more distal parts of the stem not currently known to be associated with the cup or crown. -

Further Paleomagnetic Evidence for Oroclinal Rotation in the Central Folded Appalachians from the Bloomsburg and the Mauch Chunk Formations

TECTONICS, VOL. 7, NO. 4, PAGES 749-759, AUGUST 1988 FURTHER PALEOMAGNETIC EVIDENCE FOR OROCLINAL ROTATION IN THE CENTRAL FOLDED APPALACHIANS FROM THE BLOOMSBURG AND THE MAUCH CHUNK FORMATIONS Dennis V. Kent Lamont-DohertyGeological Observatory and Departmentof GeologicalSciences ColumbiaUniversity, Palisades, New York Abstract.Renewed paleomagnetic investigations of red fromthe Bloomsburg, Mauch Chunk, and revised results bedsof theUpper Silurian Bloomsburg and the Lower recentlyreported for theUpper Devonian Catskill Formation Carboniferous Mauch Chunk Formations were undertaken togetherindicate 22.8•>+_11.9 oof relativerotation, accounting with theobjective of obtainingevidence regarding the for approximatelyhalf thepresent change in structuraltrend possibilityof oroclinalbending as contributing to thearcuate aroundthe Pennsylvania salient. The oroclinalrotation can be structuraltrend of thePennsylvania salient. These formations regardedas a tightenS.*'.3 o/'a lessarcuate depositional package cropout on both limbs of thesalient and earlier, but less thatdeveloped across a basementreentrant, to achievea definitivepaleomagnetic studies on these units indicate that curvaturecloser to that of the earlierzigzag continental margin earlyacquired magnetizations can be recovered. Oriented outline. sampleswere obtained from nine sites on the southern limb of thesalient and eight sites from the northern limb in the INTRODUCTION Bloomsburg.The naturalremanent magnetizations are multivectorial,dominated by a component(B) with a A testof the oroclinehypothesis -

Paleomagnetism of the Upper Ordovician Juniata Formation of the Central Appalachians Revisited Again

JOURNALOF GEOPHYSICALRESEARCH, VOL. 94, NO. B2, PAGES1843-1849, FEBRUARY10, 1989 PALEOMAGNETISM OF THE UPPER ORDOVICIAN JUNIATA FORMATION OF THE CENTRAL APPALACHIANS REVISITED AGAIN JohnD. Miller1 andDennis V. Kent Lamont-DohertyGeological Observatol 3, and Department of GeologicalSciences, ColumbiaUniversity, Palisades, New York Abstract.Two componentsof magnetizationwere isolated demagnetizationin thestudy of red beds.During this time in theUpper Ordovician Juniata Formation sampled in the area periodall of themajor Appalachian red beds were studied or of the Pennsylvaniasalient. The thermallydistributed, restudiedusing modem paleomagnetic techniques. The revised reversedpolarity B componentwas most likely acquired resultsfrom the Juniatawere reported by Van der Voo and duringAlleghenian deformation, and although it is poorly French[ 1977], andwere incorporatedinto the analysisof grouped,it is similarto otherAppalachian synfolding Schwartzand Van der Voo [ 1983], which concludedthat there magnetizations.The pre-Alleghenianage C magnetizationis was no oroclinal rotation involved in the formation of the entirelyof normalpolarity and showsa differencein Pennsylvaniasalient, a majorstructural feature of thecentral declinationsbetween the meanmagnetizations isolated on the Appalachians. northern and southern limbs of the salient of 24 ø _+23 ø. This Recentcontroversy regarding the Paleozoic reference poles anomalyis consistentwith the senseand magnitude of for North Americaand their tectonic implications [Kent and declinationanomalies observed -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science

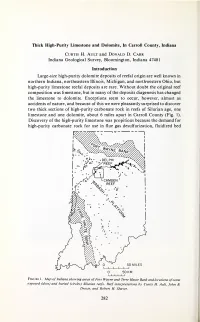

Thick High-Purity Limestone and Dolomite, In Carroll County, Indiana Curtis H. Ault and Donald D. Carr Indiana Geological Survey, Bloomington, Indiana 47401 Introduction Large -size high-purity dolomite deposits of reefal origin are well known in northern Indiana, northeastern Illinois, Michigan, and northwestern Ohio, but high-purity limestone reefal deposits are rare. Without doubt the original reef composition was limestone, but in many of the deposits diagenesis has changed the limestone to dolomite. Exceptions seem to occur, however, almost as accidents of nature, and because of this we were pleasantly surprised to discover two thick sections of high-purity carbonate rock in reefs of Silurian age, one limestone and one dolomite, about 6 miles apart in Carroll County (Fig. 1). Discovery of the high-purity limestone was propitious because the demand for high-purity carbonate rock for use in flue gas desulfurization, fluidized bed 50 MILES Figure 1 Indiana . Map of showing areas of Fort Wayne and Terre Haute Bank and locations ofsome exposed (dots) and buried (circles) Silurian reefs. Reef interpretations by Curtis H. Ault, John B. Droste, and Robert H. Shaver. 282 Geography and Geology 283 combustion, lime, glass raw materials, and chemical products has been increasing. The dolomite is currently being exploited for aggregate, but the limestone awaits commercial development. Background In 1973 the Indiana Geological Survey drilled a core hole (SDH 244) in the center of the Delphi reef as part of a study of reefs in northern Indiana by Curtis H. Ault and Robert H. Shaver. The reef was found to be 398 feet thick; this is the thickest continuous section of high-magnesium dolomite in Indiana ever analyzed by the Survey. -

Bedrock Geology of the Southern Half of the Knox 30

Bedrock Geology of the Southern Half of the TODD A. THOMPSON, STATE GEOLOGIST Knox 30- X 60-Minute Quadrangle, Indiana By Patrick I. McLaughlin, Alyssa M. Bancroft, and Matthew R. Johnson Bloomington, Indiana 2021 -86°0'00" -86°15'00" 5 000 -86°7'30" 5 000 580000E 5 000 -86°22'30" 5 000 5 000 565000E 70 E 75 E -87°0'00" -86°52'30" -86°45'00" 5 000 5 000 -86°37'30" 5 000 5 000 -86°30'00" 545000E 50 E 55 E 60 E 505 515000E 520 25 E 30 E 35 E 40 E 146859 520 10 Summit Chapel 159301 Rutland Winona 17 Y 560 Argos T Da Houghton Y Lake 158174 Da 144404 N T Da 600 Round 560 4565000N U N 4565000N O U Lake 146860 Dt C 600 162469 O E 500 S C Da 10 10 Dunns ER 162054 Bass ORT Lake 143696 Old Tip Bridge P PER 39 Town Da AS S 400 E J 162049 Da 31 W 560 143695 0 North 0 0 520 146870 1 159302 W 600 S Judson Culver MUCKSHAW RD MUCKSHAW S 10 10 146864 Tippecanoe Dt Dt Maxinkuckee Lake COUNTY MARSHALL Dt Maxinkuckee Dt COUNTY KOSCIUSKO STARKE COUNTY STARKE 560 Aldine MARSHALL COUNTY Tefft San Pierre Lost 19 Da Lena Park Lake 146875 4560000N 35 4560 Da Bass 331 560 Station 117 Da Da Hartz Da Lake 600 560 Walnut 140912 Da Mentone 421 159300 CR 800 N 25 Ora MARSHALL COUNTY STARKE COUNTY 600 STARKE COUNTY 110 110 141955 PULASKI COUNTY Langenbahn FULTON COUNTY 158173 158082 PULASKI COUNTY Lake 560 17 Dt Da Radioville Dt 520 Richland Monterey Tiosa Talma Center 136071 39 Denham 560 31 136072 45 000 45 000 55 N Dt 141952 55 N 600 Zink 141951 141959 136070 Lake Beardstown Delong 140891 Clarks 144534 Dt 560 136073 Dt 520 Sevastopol Da 140894 144535 Dt 41°7'30" Dt -

Download Download

The Backbone Limestone (Lower Devonian), a Potential Reservoir in Southern Indiana John A. Rupp Petroleum Section, Indiana Geological Survey Bloomington, Indiana 47405 Introduction Evaluation of Lower Devonian rocks (New Harmony Group), which are present only in the subsurface of southwestern Indiana, indicates that conditions exist for the presence of hydrocarbon bearing reservoirs. Moderate depths and multiplicity of possible trap configurations make this group of rocks an economically favorable exploration target. Because the units are present only in the subsurface, limited data are available for use in making paleoenvironmental reconstructions, evaluating sedimentary struc- tures, and interpreting the diagenetic history. Detailed knowledge about the distribu- tion and the composition of these Early Devonian sediments is still lacking, but renewed interest in the group is producing data that will help better define the physical and chemical characteristics of these rocks. Early in the drilling history of the Illinois Basin, rocks found along the eastern margin of the Illinois Basin below the Middle Devonian carbonate sediments (Muscatatuck Group) were interpreted to be Silurian in age. Following the work of Freeman (11) and Collinson and others (7) a clearer understanding of this wedge of carbonate and siliceous dolomitic sediments emerged. Following the recognition of Lower Devonian faunal assemblages in a core from White County, Illinois, Becker (3) defined and mapped the extent and internal stratigraphy of Lower Devonian rocks in southwestern Indiana. Through the work of Becker (3) and Becker and Droste (5) the regional distribution of the major lithostratigraphic units within the group (Grassy Knob Chert, Backbone Limestone, and Clear Creek Chert) was recognized. -

Caledonian-Appalachian Orogen Palaeomagnetic Constraints on The

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ at Columbia University on January 17, 2012 Geological Society, London, Special Publications Palaeomagnetic constraints on the evolution of the Caledonian-Appalachian orogen J. C. Briden, D. V. Kent, P. L. Lapointe, J. L. Roy, R. A. Livermore, A. G. Smith, M. K. Seguin, R. Van der Voo and D. R. Watts Geological Society, London, Special Publications 1988, v.38; p35-48. doi: 10.1144/GSL.SP.1988.038.01.03 Email alerting click here to receive free e-mail alerts when service new articles cite this article Permission click here to seek permission to re-use all or request part of this article Subscribe click here to subscribe to Geological Society, London, Special Publications or the Lyell Collection Notes © The Geological Society of London 2012 Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ at Columbia University on January 17, 2012 Palaeomagnetic constraints on the evolution of the Caledonian- Appalachian orogen J. C. Briden, D. V. Kent, P. L. Lapointe, R. A. Livermore, J. L. Roy, M. K. Seguin, A. G. Smith, R. Van der Voo & D. R. Watts SUMMARY: Late Proterozoic and Palaeozoic (pre-Permian) palaeomagnetic data from all regions involved in, or adjacent to, the Caledonian-Appalachian orogenic belt are reviewed. Between about 1100 and about 800 Ma the Laurentian and Baltic shields were close together, prior to the opening phase of the Caledonian-Appalachian Wilson cycle. The problems of tectonic interpretation of Palaeozoic palaeomagnetic data from within and around the belt derive mostly from differences of typically 10°-20° between the pole positions. These can variously be interpreted in terms of (i) relative displacements between different continents or terranes, (ii) differences in ages of remanence and (iii) aberrations due to inadequacy of data or geomagnetic complexity, and it is not always easy to discriminate between these alternatives. -

Environmental Setting and Natural Factors and Human Influences Affecting Water Quality in the White River Basin, Indiana

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Environmental Setting and Natural Factors and Human Influences Affecting Water Quality in the White River Basin, Indiana Water-Resources Investigations Report 97-4260 White River Basin National Water-Quality Assessment Study Unit National Water-Quality Assessment Program science foruses a changing world U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Environmental Setting and Natural Factors and Human Influences Affecting Water Quality in the White River Basin, Indiana By Douglas J. Schnoebelen, Joseph M. Fenelon, Nancy I Baker, Jeffrey D. Martin, E. Randall Bayless, David V. Jacques, and Charles G. Crawford National Water-Quality Assessment Program Water-Resources Investigations Report 97-4260 Indianapolis, Indiana 1999 U.S. Department of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director The use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. For additional information, write to: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey Water Resources Division 5957 Lakeside Boulevard Indianapolis, IN 46278-1996 Copies of this report can be purchased from: U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Box 25286 Federal Center Denver, CO 80225-0286 Information regarding the National Water-Quality Assessment (NAWQA) Program is available on the Internet via the World Wide Web. You can connect to the NAWQA Home Page using the Universal Resource Locator (URL) at: <URL:http://wwwrvares.er.usgs.gov/nawqa/nawqa_home.html> Foreword The mission of the U.S. Geological Survey Describe how water quality is changing over (USGS) is to assess the quantity and quality of the time. -

Ground-Water Resources in the White and West Fork White River Basin, Indiana

GROUND-WATER RESOURCES IN THE WHITE AND WEST FORK WHITE RIVER BASIN, INDIANA STATE OF INDIANA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WATER 2002 GROUND-WATER RESOURCES IN THE WHITE AND WEST FORK WHITE RIVER BASIN, INDIANA STATE OF INDIANA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WATER Water Resource Assessment 2002-6 Printed By Authority of the State of Indiana Indianapolis, Indiana: 2002 STATE OF INDIANA Frank O'Bannon, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES John Goss, Director DIVISION OF WATER Michael W. Neyer, Director Project Manager: Judith E. Beaty Editor: Judith E. Beaty This report was prepared by the Basin Studies Section Greg Schrader and Ralph Spaeth And The Ground Water Section Bill Herring, Glenn Grove, and Randy Meier For sale by Division of Water, Indianapolis, Indiana CONTENTS page INTRODUCTION . .1 Purpose and scope . .1 Previous investigations . .1 Acknowledgements . .3 GEOLOGY . .4 Sources of geologic data . .4 Regional physiography . .4 Overview of glacial history and deposits . .5 Summary of major Quaternary deposits . .9 Glacial terrains . .10 Bedrock geology . .12 Bedrock physiography . .13 Bedrock stratigraphy and lithology . .14 GROUND-WATER HYDROLOGY . .19 Ground-water resources . .19 Ground-water levels . .19 Potentiometric surface maps . .21 Aquifer systems . .21 Unconsolidated aquifer systems . .21 Tipton Till Plain Aquifer System . .24 Tipton Till Plain Aquifer Subsystem . .27 Dissected Till and Residuum Aquifer System . .29 White River and Tributaries Outwash Aquifer System . .29 White River and Tributaries Outwash Aquifer Subsystem . .29 Buried Valley Aquifer System . .30 Lacustrine and Backwater Deposits Aquifer System . .30 Bedrock aquifer systems . .30 Ordovician/Maquoketa Group . .31 Silurian and Devonian Carbonates . .32 Devonian and Mississippian/ New Albany Shale . -

Development of a Procedure to Identify Aggregate for Bituminous Surfaces in Indiana

Final Report FHW A/IN/JTRP-2000/28 DEVELOPMENT OF A PROCEDURE TO IDENTIFY AGGREGATES FOR BITUMINOUS SURFACES IN INDIANA Terry R. West Professor Principal Investigator and Kyu H. Cho Research Assistant Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Purdue University Joint Transportation Research Program Project No. C-36-6RR File No. 2-4-44 SPR-2206 Prepared in cooperation with the Indiana Department of Transportation and the U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Indiana Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration at the time of publication. This report does not constitute a standard, specificationor regulation. Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana September 2001 TECHNICAL REPORT STANDARD TITLE PAGE 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHW A/IN/JTRP-2000/28 4. Title and Snbtllle S. Report Date September 2001 Development of a Procedure to Identify Aggregate for Bituminous Surfaces in Indiana 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8, Performing Organization Report No. Terry R. West and Kyu H. Cho FHWA/IN/JTRP-2000/28 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Joint Transportation Research Program 1284 Civil Engineering Building Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-1284 11. Contract or Grant No. SPR-2206 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Indiana Department of Transportation State Office Building Final Report 100 North Senate Avenue Indianaoolis. -

Geology and Structure of the Rough Creek Area, Western Kentucky William D. Johnson Jr. U.S. Geological Survey, Emeritus and Howa

Kentucky Geological Survey James C. Cobb, State Geologist and Director University of Kentucky, Lexington Geology and Structure of the Rough Creek Area, Western Kentucky William D. Johnson Jr. U.S. Geological Survey, Emeritus and Howard R. Schwalb Kentucky Geological Survey and Illinois State Geological Survey, Retired Nomenclature and structure contours do not necessarily conform to current U.S. Geological Survey or Kentucky Geological Survey usage. This work was originally prepared in the late 1990’s and is published here with only editorial improvements. Bulletin 1 Series XII, 2010 Our Mission Our mission is to increase knowledge and understanding of the mineral, energy, and water resources, geologic hazards, and geology of Kentucky for the benefit of the Commonwealth and Nation. © 2006 University of Kentucky Earth Resources—OurFor further information Common contact: Wealth Technology Transfer Officer Kentucky Geological Survey 228 Mining and Mineral Resources Building University of Kentucky Lexington, KY 40506-0107 www.uky.edu/kgs ISSN 0075-5591 Technical Level Technical Level General Intermediate Technical General Intermediate Technical ISSN 0075-5559 Contents Abstract .........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................7 Geologic Setting.........................................................................................................................................10