Image of the Region in Eurasian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communists and the Labour Party

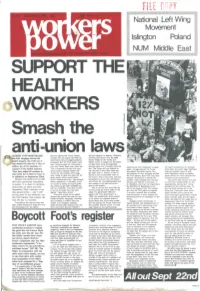

FILE , I cnpv National ~ Left·Wing Movement Islington Poland NUM Middle East ::.;:~:;:;:;:;::::::::::::::::::::::::::~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:;:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~::::::::;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:;:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:;:;~~~~~: THE HEALTH Smash,the anti-union laws. Al.-MOST FIVE MONTHS after workers against the Tories. Miners, Bill 't~e designed to destroy. Effective he firSt stoppage during the dockers and, of cour,se, tile Fleet St. working class action is ,to be made totally illegal by the Tories. Suc ealth dispute, the TUC has at electricians, hBve. all '$taged solidarity stoppages. But the TUC leaders have cessful action in support of the health last named the date for a Day of been running scared of a showdown workers must bring the organised Action, by all its ~embers, in with the Tories. Even now, when the working class into a collision with the battle could have threatened to spear the health workers and on strength support of the health workers. TUC is eventually forced into supp law. The Tories will not hesitate to head a struggle against the Tories ening their anti-union legal machinery They have asked all workers to orti ng action, because neither the use that law if they think they can throughout the public sector. But with yet another round of anti- get away with it. Victory in this in stop work for at least an hour in Tories nor the workers will budge, the prospect of such struggles terrifies union legislation aimed at making they refuse to issue any clear call for stance is sure to embolden them in the TUC leaders. Each time they have secret ballots for union officials and in solidarity on Septemller 22nd. -

British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 William Styles Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge September 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy William Styles British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 This thesis is concerned with an analysis of British governmental attitudes and responses to communism in the United Kingdom during the early years of the Cold War, from the election of the Attlee government in July 1945 up until the election of the Wilson government in October 1964. Until recently the topic has been difficult to assess accurately, due to the scarcity of available original source material. However, as a result of multiple declassifications of both Cabinet Office and Security Service files over the past five years it is now possible to analyse the subject in greater depth and detail than had been previously feasible. The work is predominantly concerned with four key areas: firstly, why domestic communism continued to be viewed as a significant threat by successive governments – even despite both the ideology’s relatively limited popular support amongst the general public and Whitehall’s realisation that the Communist Party of Great Britain presented little by way of a direct challenge to British political stability. Secondly, how Whitehall’s understanding of the nature and severity of the threat posed by British communism developed between the late 1940s and early ‘60s, from a problem considered mainly of importance only to civil service security practices to one which directly impacted upon the conduct of educational policy and labour relations. -

India's Relations with Russia : 1992-2002 Political

INDIA'S RELATIONS WITH RUSSIA : 1992-2002 ABSTRACT THESIS . SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD GREE OF irfar of 3fflliliJ!50pl{g O POLITICAL SCIENCE I u Mi^ BY BDUL AZEEM Under the Supervision of Prof. Ms. Iqbal Khanam DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ^^^ ^ ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2006 ABSTRACT India's friendly stance towards the USSR has greatly been exaggerated, misunderstood and misinterpreted in India and abroad. An examination of the subject appeared necessary in order to explain the nature, extent, direction and implications of India's relations with the USSR. An attempt has been made here to analyze India's policy towards the USSR and place it in proper perspective. The ever growing friendly relations between the two neighbours are the result of many factors such as the complementarily of their national interests and the constantly changing national and international situations. The Soviet Union's huge size, its vast potentialities and the geo-political situation compelled Indian leaders, Jawaharlal Nehru in particular, to realize, even before India attained independence, the need to develop close and friendly relations with the Soviet Union. India's attitude towards the USSR has been derived from its overall foreign policy objectives. In understanding and evaluating this attitude, it is therefore, indispensable to keep in view two important considerations: first, the assumptions, motivations, style, basic goals and the principles of India's foreign policy which governed her relations with other States in general; second, the specific goals which India sought to achieve in her relations with the USSR. It is the inter-relationship between the general and the particular objectives and the degree of their combination as well as contradiction that give us an idea of the various phases of India's relations with the USSR. -

Aleksandra Khokhlova

Aleksandra Khokhlova Also Known As: Aleksandra Sergeevna Khokhlova, Aleksandra Botkina Lived: November 4, 1897 - August 22, 1985 Worked as: acting teacher, assistant director, co-director, directing teacher, director, film actress, writer Worked In: Russia by Ana Olenina Today Aleksandra Khokhlova is remembered as the star actress in films directed by Lev Kuleshov in the 1920s and 1930s. Indeed, at the peak of her career she was at the epicenter of the Soviet avant-garde, an icon of the experimental acting that matched the style of revolutionary montage cinema. Looking back at his life, Kuleshov wrote: “Nearly all that I have done in film directing, in teaching, and in life is connected to her [Khokhlova] in terms of ideas and art practice” (1946, 162). Yet, Khokhlova was much more than Kuleshov’s wife and muse as in her own right she was a talented author, actress, and film director, an artist in formation long before she met Kuleshov. Growing up in an affluent intellectual family, Aleksandra would have had many inspiring artistic encounters. Her maternal grandfather, the merchant Pavel Tretyakov, founder of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, was a philanthropist and patron who purchased and exhibited masterpieces of Russian Romanticism, Realism, and Symbolism. Aleksandra’s parents’ St. Petersburg home was a prestigious art salon and significant painters, actors, and musicians were family friends. Portraits of Aleksandra as a young girl were painted by such eminent artists as Valentin Serov and Filipp Maliavin. Aleksandra’s father, the doctor Sergei Botkin, an art connoisseur and collector, cultivated ties to the World of Arts circle–the creators of the Ballets Russes. -

WORLD FILM LOCATIONS MOSCOW Edited by Birgit Beumers

WORLD FILM LOCATIONS MOSCOW Edited by Birgit Beumers WORLD FILM LOCATIONS MOSCOW Edited by Birgit Beumers First Published in the UK in 2014 by All rights reserved. No part of this Intellect Books, The Mill, Parnall Road, publication may be reproduced, stored Fishponds, Bristol, BS16 3JG, UK in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, First Published in the USA in 2014 mechanical, photocopying, recording, by Intellect Books, The University of or otherwise, without written consent. Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA A Catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright ©2014 Intellect Ltd World Film Locations Series Cover photo: Night Watch (2004) ISSN: 2045-9009 Bazelevs Production / Channel One eISSN: 2045-9017 Russia / The Kobal Collection World Film Locations Copy Editor: Emma Rhys ISBN: 978-1-78320-196-9 Typesetting: Jo Amner ePDF ISBN: 978-1-78320-267-6 ePub ISBN: 978-1-78320-268-3 Printed and bound by Bell & Bain Limited, Glasgow WORLD FILM LOCATIONS MOSCOW editor Birgit Beumers series editor & design Gabriel Solomons contributors José Alaniz Erin Alpert Nadja Berkovich Vincent Bohlinger Rad Borislavov Vitaly Chernetsky Frederick Corney Chip Crane Sergey Dobrynin Greg Dolgopolov Joshua First Rimma Garn Ian Garner Tim Harte Jamie Miller Jeremy Morris Stephen M. Norris Sasha Razor John A. Riley Sasha Rindisbacher Tom Roberts Peter Rollberg Larissa Rudova Emily Schuckman Matthews Sasha Senderovich Giuliano Vivaldi location photography Birgit Beumers -

Lyubov Orlova: Stalinism’S Shining Star,’ Senses of Cinema, Issue 23: the Female Actor, December 2002

Dina Iordanova, ‘Lyubov Orlova: Stalinism’s Shining Star,’ Senses of Cinema, Issue 23: The Female Actor, December 2002. Available: https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2002/the-female-actor/orlova/ Lyubov Orlova: Stalinism’s Shining Star Dina Iordanova Issue 23 A Lyubov Orlova filmography appears at the bottom of this article. A misguided assumption about Soviet cinema, which still persists, is that it’s a national cinema mostly comprised of depressing war dramas in which popular genres were neglected and even suppressed. This is certainly not the picture of Soviet cinema I remember when, 1 growing up in 1960s Bulgaria, I could enjoy a fair share of popular films, like the Soviet action-adventure Neulovimyye mstiteli/The Elusive Avengers (1966) or Yuri Nikulin’s superb comedies, all playing in theatres alongside the comedies of Louis de Funès or Raj Kapoor’s ever-popular weepy Awara/The Vagabond (1951). A highlight was Eldar Ryazanov’s musical, Karnavalnaya noch/Carnival Night (1956), with Lyudmila Gurchenko’s unforgettable dancing and singing. Made several years before I was even born, Carnival Night was so popular that by the time I started watching movies it was still regularly playing in theatres as well as being shown on television. Here, a buoyant and beautiful Lydmila Gurchenko leads a group of amateur actors to undermine the plans of the Culture Ministry and its boring leadership in order to turn a New Year’s Eve celebration into an exciting vibrant extravaganza, with confetti, sparklers and crackers. It was only later, in my teenage years when I started visiting the Sofia Cinémathèque, that I realized how Carnival Night in many aspects replicated Grigoriy Aleksandrov’s musical extravaganzas of the 1930s. -

Women and Martyrdom in Soviet War Cinema of the Stalin Era

Women and Martyrdom in Soviet War Cinema of the Stalin Era A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Mozhgan Samadi School of Arts, Languages and Cultures CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES 5 ABSTRACT 6 DECLARATION 7 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT 7 A NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION 8 ACKNOWLEGEMENTS 9 THE AUTHOR 10 Introduction: Background and Aims 12 Thesis Rationale: Female Role Models and Soviet Identity-Building 15 Literature Review: Existing Scholarship on Women and Martyrdom in Stalinist War Cinema 20 Aims, Objectives and Research Questions of the Thesis 26 Original Contribution to Knowledge 28 Structure of the Thesis 29 Chapter One: Historical and Ideological Context 1.1 Introduction 32 1.2 Russian Orthodox Political Culture 33 1.2.1 Russian Orthodoxy and the Values of Suffering and Martyrdom 33 1.2.2 Orthodox Princes: The Role Models of Sacrificing the Self for Faith and the ‘Holy’ Lands of Rus’ 35 1.3 The Ideas of ‘Holy’ Rus’ and Russian Messianism and the Adoption of the Russian Orthodox Traditions of Suffering and Martyrdom in the 19th Century 38 1.4 Soviet Reinterpretation of Russian Orthodox Values of Suffering and Martyrdom 44 1.4.1 Resurrection of the Idea of Russian Messianism under the Name of 2 Soviet Messianism 44 1.4.2 The Myth of the Great Soviet Family 51 1.5 Conclusion 54 Chapter Two: Theory and Methodology 2.1 Introduction 57 2.2 Women and Martyrdom in Russia and the Soviet Union 57 2.2.1 The Russian Orthodox Valorisation of Suffering and Female Believers 57 -

Turkey's Return to the Muslim Balkans by Kerem Öktem

New Islamic actors after the Wahhabi intermezzo: Turkey’s return to the Muslim Balkans By Kerem Öktem European Studies Centre, University of Oxford December 2010 New Islamic actors after the Wahhabi intermezzo: Turkey’s return to the Muslim Balkans | Kerem Öktem |Oxford| 2010 New Islamic actors after the Wahhabi intermezzo: Turkey’s return to the Muslim Balkans1 By Kerem Öktem St Antony's College, University of Oxford [email protected] Introduction The horrific events of 9/11 solidified Western popular interest in Islamic radicalism2, empow- ered particular discourses on religion as an all-encompassing identity (cf. Sen 2006) and cre- ated new bodies of research. International organizations, governments, academic institutions and independent research centres became keen on supporting a wide range of scholarly explor- ations of interfaith understanding—issues of identity and Muslim minority politics. Thus, a great many journal articles and edited volumes on Islam in Australia (e.g. Dunn 2004, 2005), Europe (e.g. Nielsen 2004; Hunter 2002), Canada (e.g. Isin and Semiatiki 2002) and the United States (Metcalf 1996) were published mainly by experts on the Middle East, theologians, po- litical scientists, human geographers and anthropologists. Simultaneously, security analysts and think-tankers produced numerous studies on the threat of Islamic terrorism, focusing on the activities of Osama Bin Laden and Al-Qaida. It was in this context that a new body of neocon- 1 Paper first presented at the international workshop ‘After the Wahabi Mirage: Islam, politics and international networks in the Balkans’ at the European Studies Centre, University of Oxford in June 2010. -

Soviet Cinema

Soviet Cinema: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942 Where to Order BRILL AND P.O. Box 9000 2300 PA Leiden The Netherlands RUSSIA T +31 (0)71-53 53 500 F +31 (0)71-53 17 532 BRILL IN 153 Milk Street, Sixth Floor Boston, MA 02109 USA T 1-617-263-2323 CULTURE F 1-617-263-2324 For pricing information, please contact [email protected] MASS www.brill.nl www.idc.nl “SOVIET CINemA: Film Periodicals, 1918-1942” collections of unique material about various continues the new IDC series Mass Culture and forms of popular culture and entertainment ENTERTAINMENT Entertainment in Russia. This series comprises industry in Tsarist and Soviet Russia. The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment in Russia The IDC series Mass Culture & Entertainment diachronic dimension. It includes the highly in Russia comprises collections of extremely successful collection Gazety-Kopeiki, as well rare, and often unique, materials that as lifestyle magazines and children’s journals offer a stunning insight into the dynamics from various periods. The fifth sub-series of cultural and daily life in Imperial and – “Everyday Life” – focuses on the hardship Soviet Russia. The series is organized along of life under Stalin and his somewhat more six thematic lines that together cover the liberal successors. Finally, the sixth – “High full spectrum of nineteenth- and twentieth Culture/Art” – provides an exhaustive century Russian culture, ranging from the overview of the historic avant-garde in Russia, penny press and high-brow art journals Ukraine, and Central Europe, which despite in pre-Revolutionary Russia, to children’s its elitist nature pretended to cater to a mass magazines and publications on constructivist audience. -

Leto (2018) 7.30Pm Cine Lumière by Kirill Serebrennikov

31 January 2020 Melodia! Discovering Musicals 31 January Leto (2018) 7.30pm Cine Lumière by Kirill Serebrennikov Kirill Serebrennikov’s Leto deals with history that has a vital The soundtrack includes songs by both men, as well as some place in contemporary Russia’s sense of itself and its brilliant evocations of what might have happened in the relationship to the Soviet past. From the mid-1960s onwards, characters’ heads when they hummed songs by T. Rex, Talking the Soviet Union thronged with fans of western rock music. In Heads or Lou Reed. Tsoi’s songs are somewhat better known the cities, over what turned out to be the last two-and-a-bit than Mike’s, but, as the film tells us, Mike was a huge influence decades of Soviet rule, lively music scenes developed. These on the development of rock in Russian. To his fellow musicians scenes encompassed bands that mainly wrote and performed he, more than anyone else in Leningrad, seemed the their own songs and that were denied opportunities to make embodiment of a kind of primeval essence of rock and roll – records or publicise their music via state media, until the though aside from instinct this was something at which he advent of Gorbachev and perestroika. By the late 1970s, the studied hard: he sought out records, listened widely, he paradox of the obvious popularity some bands had transcribed and translated lyrics, read everything he could get nonetheless achieved and the haphazard circumstances in his hands on (as a result, his English was extremely good). -

The Russian Cinematic Culture

Russian Culture Center for Democratic Culture 2012 The Russian Cinematic Culture Oksana Bulgakova Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Repository Citation Bulgakova, O. (2012). The Russian Cinematic Culture. In Dmitri N. Shalin, 1-37. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture/22 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Article in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Culture by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Russian Cinematic Culture Oksana Bulgakova The cinema has always been subject to keen scrutiny by Russia's rulers. As early as the beginning of this century Russia's last czar, Nikolai Romanov, attempted to nationalize this new and, in his view, threatening medium: "I have always insisted that these cinema-booths are dangerous institutions. Any number of bandits could commit God knows what crimes there, yet they say the people go in droves to watch all kinds of rubbish; I don't know what to do about these places." [1] The plan for a government monopoly over cinema, which would ensure control of production and consumption and thereby protect the Russian people from moral ruin, was passed along to the Duma not long before the February revolution of 1917. -

Soviet Science Fiction Movies in the Mirror of Film Criticism and Viewers’ Opinions

Alexander Fedorov Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions Moscow, 2021 Fedorov A.V. Soviet science fiction movies in the mirror of film criticism and viewers’ opinions. Moscow: Information for all, 2021. 162 p. The monograph provides a wide panorama of the opinions of film critics and viewers about Soviet movies of the fantastic genre of different years. For university students, graduate students, teachers, teachers, a wide audience interested in science fiction. Reviewer: Professor M.P. Tselysh. © Alexander Fedorov, 2021. 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 1. Soviet science fiction in the mirror of the opinions of film critics and viewers ………………………… 4 2. "The Mystery of Two Oceans": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………….. 117 3. "Amphibian Man": a novel and its adaptation ………………………………………………………………….. 122 3. "Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin": a novel and its adaptation …………………………………………….. 126 4. Soviet science fiction at the turn of the 1950s — 1960s and its American screen transformations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 130 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 136 Filmography (Soviet fiction Sc-Fi films: 1919—1991) ……………………………………………………………. 138 About the author …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 150 References……………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………….. 155 2 Introduction This monograph attempts to provide a broad panorama of Soviet science fiction films (including television ones) in the mirror of