The EU-India Partnership: Time to Go Strategic? Institute for Security Studies Security for Institute European Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[28 DEC. 1989] on the President's 202 Address](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3782/28-dec-1989-on-the-presidents-202-address-33782.webp)

[28 DEC. 1989] on the President's 202 Address

201 Motion of thanks [28 DEC. 1989] on the President's 202 Address SHRI DINESH GOSWAMI: Madam, I THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDE- also beg to lay on the Table a copy each (in PENDENT CHARGE) OF THE MINISTRY English and Hindi, ) of the following papers; OF WATER RESOURCES (SHRI MANOBHAI KOTADIA); Madam, I beg to I. (i) Thirty-first Annual Report and lay on the Table, under sub-section (1) Accounts of the Indian Law Institute, section 619A of tie Companies Act, 1956, a New Delhi, for the year 1987-88, to- copy each (in English and Hindi) of the gether with the Audit Report on the followng papers; — Accounts, (i) Twentieth Annual Report and Accounts (ii) Statement by Government accepting of the Water and Power. Consultancy the above Report. Services (India). Limited, New Delhi, for the year. 1988—89, together with the (iii) Statement giving reasons for the delay Auditor's Report on the Accounts and in laying the paper mentioned at (i) above. the comments of the Comptroller and [Placed in Library. See No. LT— 244/89 Auditor General of India thereon, for (i) to (iii)]. (ii) Review by Government on the II. A copy (in English and Hindi) of working of the Company. the Ministry of Law and Justice (Legisla [Placed in Library. See No. LT— tive Department) Notification S. O. No. 61/89]. 958(E), dated the 17th November, 1989, publishing the Conduct of Election; (Third Amendment) Rules, 1989, under section 169 of the Representation of the REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON People Act, 1951. -

Stop Mass Atrocities. Advancing EU Cooperation with Other

ISSN 2239-2122 7 The cooperation between the European Union and the United Nations, as well as other S IAI Research Papers regional organizations, is assuming an increasingly important role in the prevention of TOP The IAI Research Papers are brief monographs written by one or mass atrocities and implementation of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). The present M more authors (IAI or external experts) on current problems of inter- N. 1 European Security and the Future of Transatlantic Relations, TOP ASS TROCITIES ASS S M A report, which is the result of a joint eort between the IAI in Rome and the EUISS in national politics and international relations. The aim is to promote edited by Riccardo Alcaro and Erik Jones, 2011 A greater and more up to date knowledge of emerging issues and Paris, has been conceived as a mapping exercise of the EU's ongoing and potential TROCITIES DVANCING OOPERATION WITH N. 2 Democracy in the EU after the Lisbon Treaty, partnerships with other international organizations (namely the United Nations, the A EU C trends and help prompt public debate. edited by Raaello Matarazzo, 2011 North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in OTHER INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS Europe, the Council of Europe, the African Union, the Arab League, the Association of N. 3 The Challenges of State Sustainability in the Mediterranean, South-East Asian Nations and the Organization of American States) in these elds. The A non-prot organization, IAI was founded in 1965 by Altiero Spinelli, edited by Silvia Colombo and Nathalie Tocci, 2011 aim of the report is to assess both best practices and gaps, including areas that have not its rst director. -

Transition in Afghanistan 2012

TRANSITION IN AFGHANISTAN 2011-2014 Five Parliamentary Studies NATO Parliamentary Assembly Founded in 1955, the NATO Parliamentary Assembly (NATO PA) serves as the consultative inter-parliamentary organisation for the North Atlantic Alliance. Bringing together members of parliaments throughout the Atlantic Alliance, the NATO PA provides an essential link between NATO and the parliaments of its member nations, helping to build parliamentary and public consensus in support of Alliance policies. At the same time, it facilitates parliamentary awareness and understanding of key security issues and contributes to a greater transparency of NATO policies. Crucially, it helps maintain and strengthen the transatlantic relationship, which underpins the Atlantic Alliance. Since the end of the Cold War the Assembly has assumed a new role by integrating into its work parliamentarians from those countries in Central and Eastern Europe and beyond who seek a closer association with NATO. This integration has provided both political and practical assistance and has contributed to the strengthening of parliamentary democracy throughout the Euro-Atlantic region, thereby complementing and reinforcing NATO’s own programme of partnership and co-operation. The headquarters of the Assembly’s 30-strong International Secretariat staff members is located in central Brussels. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Declaration 392 on Supporting Transition in Afghanistan presented by Hugh Bayley 7 Governance Challenges in Afghanistan: An Update by Vitalino Canas 13 Transition in Afghanistan: Assessing the Security Effort by Sven Mikser Finding Workable Solutions in Afghanistan: the Work of the International Community in Building a Functioning Economy and Society by Jeppe Kofod 95 Afghanistan – The Regional Context by John Dyrby Paulsen 139 Countering the Afghan Insurgency: Low-Tech Threats, High-Tech Solutions by Sen. -

Arria-Formula Meetings, 1992-2019

Arria-Formula Meetings, 1992-2019 This table has been jointly compiled by Sam Daws and Loraine Sievers, as co-authors of The Procedure of the UN Security Council, and the staff of Security Council Report. The support extended by the Security Council Affairs Division in the compilation of the list is hereby recognised and greatly appreciated. ARRIA-FORMULA MEETINGS, 1992-2019 DATE SUBJECT/DOCUMENT IN WHICH INVITEE(S) ORGANISER(S) THE MEETING WAS MENTIONED Mar. 1992 Bosnia and Herzegovina; S/1999/286; Fra Jozo Zovko (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Venezuela ST/PSCA/1/Add.12 18 Dec. 1992 Persecution of Shiite ‘Marsh Arabs’ M.P. Emma Nicholson (UK) Venezuela, Hungary in Iraq 3 Mar. 1993 Bosnia and Herzegovina Alija Izetbegović, President of Bosnia and Herzegovina 24 Mar. 1993 Former Yugoslavia David Owen and Cyrus Vance, Co-Chairs of the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia 15 Apr. 1993 South Africa Richard Goldstone, Chair of the Commission of Inquiry regarding Venezuela the Prevention of Public Violence and Intimidation in South Africa 25 June 1993 Bosnia and Herzegovina Contact Group of the Organization of the Islamic Conference 12 Aug. 1993 Bosnia and Herzegovina Organization of the Islamic Conference ministerial mission 6 Sept. 1993 Bosnia and Herzegovina Alija Izetbegović, President of Bosnia and Herzegovina 28 Sept. 1993 Croatia Permanent Representative of Croatia 2 Mar. 1994 Georgia Eduard Shevardnadze, President of Georgia Czech Republic 18 Mar. 1994 Croatia Franjo Tudjman, President of Croatia 11 Apr. 1994 Bosnia and Herzegovina Vice President of Bosnia and Herzegovina 26 May 1994 Central America Alfredo Cristiani, President of El Salvador 6 July 1994 Haiti Permanent Representative of the Dominican Republic 17 Nov. -

India-Brazil Bilateral Relations Are in a State of Clearly Discernible Upswing

India-Brazil Relations Political: India-Brazil bilateral relations are in a state of clearly discernible upswing. Although the two countries are divided by geography and distance, they share common democratic values and developmental aspirations. Both are large developing countries, each an important player in its region, both stable, secular, multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, large democracies as well as trillion-dollar economies. There has been frequent exchange of VVIP, Ministerial and official-level visits in recent years resulting in strengthening of bilateral relationship in various fields. Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding for 2006 and Indira Gandhi Prize for Peace, Disarmament and Development for 2010 was conferred on President Lula. Our shared vision of the evolving global order has enabled forging of close cooperation and coordination in the multilateral arena, be in IBSA, BRICS, G-4, BASIC, G-20 or other organizations. VVIP visits from India: Vice President S. Radhakrishnan (1954), Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (1968), Prime Minister Narasimha Rao (1992 - for Earth Summit), President K.R. Narayanan (1998), Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh (2006 and April 2010) ,President Pratibha Patil (2008) and Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh (June 2012-for Rio+20 summit). Other important visits from India in recent years: Kumari Selja, Minister of State of Urban Development and Poverty Alleviation, Mr. Anand Sharma, Minister of State for External Affairs, Mr. Rao Inderjit Singh, Minister of State for Defence Production, Mr. Subodh Kant Sahai, Minister of State for Food Processing Industries, Shri Pranab Mukherjee, Minister of External Affairs (Feb 2008), Shri P. Chidambaram, Finance Minister from India (Nov 2008) and Shri S.M. -

Political Economy of India's Fiscal and Financial Reform*

Working Paper No. 105 Political Economy of India’s Fiscal and Financial Reform by John Echeverri-Gent* August 2001 Stanford University John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Building 366 Galvez Street | Stanford, CA | 94305-6015 * Associate Professor, Department of Government and Foreign Affairs, University of Virginia 1 Although economic liberalization may involve curtailing state economic intervention, it does not diminish the state’s importance in economic development. In addition to its crucial role in maintaining macroeconomic stability, the state continues to play a vital, if more subtle, role in creating incentives that shape economic activity. States create these incentives in a variety of ways including their authorization of property rights and market microstructures, their creation of regulatory agencies, and the manner in which they structure fiscal federalism. While the incentives established by the state have pervasive economic consequences, they are created and re-created through political processes, and politics is a key factor in explaining the extent to which state institutions promote efficient and equitable behavior in markets. India has experienced two important changes that fundamentally have shaped the course of its economic reform. India’s party system has been transformed from a single party dominant system into a distinctive form of coalitional politics where single-state parties play a pivotal role in making and breaking governments. At the same time economic liberalization has progressively curtailed central government dirigisme and increased the autonomy of market institutions, private sector actors, and state governments. In this essay I will analyze how these changes have shaped the politics of fiscal and financial sector reform. -

The Drivers and Dynamics of Illicit Financial Flows from India: 1948-2008

The Drivers and Dynamics of Illicit Financial Flows from India: 1948-2008 Dev Kar November 2010 The Drivers and Dynamics of Illicit Financial Flows from India: 1948-2008 Dev Kar1 November 2010 Global Financial Integrity Wishes to Thank The Ford Foundation for Supporting this Project 1 Dev Kar, formerly a Senior Economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), is Lead Economist at Global Financial Integrity (GFI) at the Center for International Policy. The author would like to thank Karly Curcio, Junior Economist at GFI, for excellent research assistance and for guiding staff interns on data sources and collection. He would also like to thank Raymond Baker and other staff at GFI for helpful comments. Finally, thanks are due to the staff of the IMF’s Statistics Department, the Reserve Bank of India, and Mr. Swapan Pradhan of the Bank for International Settlements for their assistance with data. Any errors that remain are the author’s responsibility. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of GFI or the Center for International Policy. Contents Letter from the Director . iii Abstract . v Executive Summary . vii I. Introduction . 1 II. Salient Developments in the Indian Economy Since Independence . 5 1947-1950 (Between Independence and the Creation of a Republic) . 5 1951-1965 (Phase I) . 6 1966-1981 (Phase II) . 7 1982-1988 (Phase III) . 8 1989-2008 (Phase IV) . 8 1991 Reform in the Historical Context . 10 III. The Evolution of Illicit Financial Flows . 13 Methods to Estimate Illicit Financial Flows . 13 Limitations of Economic Models . 15 Reasons for Rejecting Traditional Methods of Capital Flight . -

India's Relations with Russia : 1992-2002 Political

INDIA'S RELATIONS WITH RUSSIA : 1992-2002 ABSTRACT THESIS . SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD GREE OF irfar of 3fflliliJ!50pl{g O POLITICAL SCIENCE I u Mi^ BY BDUL AZEEM Under the Supervision of Prof. Ms. Iqbal Khanam DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ^^^ ^ ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2006 ABSTRACT India's friendly stance towards the USSR has greatly been exaggerated, misunderstood and misinterpreted in India and abroad. An examination of the subject appeared necessary in order to explain the nature, extent, direction and implications of India's relations with the USSR. An attempt has been made here to analyze India's policy towards the USSR and place it in proper perspective. The ever growing friendly relations between the two neighbours are the result of many factors such as the complementarily of their national interests and the constantly changing national and international situations. The Soviet Union's huge size, its vast potentialities and the geo-political situation compelled Indian leaders, Jawaharlal Nehru in particular, to realize, even before India attained independence, the need to develop close and friendly relations with the Soviet Union. India's attitude towards the USSR has been derived from its overall foreign policy objectives. In understanding and evaluating this attitude, it is therefore, indispensable to keep in view two important considerations: first, the assumptions, motivations, style, basic goals and the principles of India's foreign policy which governed her relations with other States in general; second, the specific goals which India sought to achieve in her relations with the USSR. It is the inter-relationship between the general and the particular objectives and the degree of their combination as well as contradiction that give us an idea of the various phases of India's relations with the USSR. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

TRAFFIC Post, India Office Newsletter (PDF)

• South Asia unites to curb illegal • India ranks highest in Tiger parts Pg 8 trade in endangered wildlife seizure over last decade • Officers from Uttar Pradesh, Pg 3 Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal sharpen skills on wildlife law enforcement • Raja and Jackie: The new ATE champions fighting wildlife Pg 3 crime • World leaders echo support to IN FOCUS ensure doubling of world's wild Pg 4 India TRAFFIC © Tiger population • Efforts augmented to ensure sustainable harvesting and trade Pg 4 TRAFFIC Alert (Latest news on of MAPs illegal wildlife trade in India): Pg 5 • TRAFFIC India's film “Don't Buy T Trouble” now available in Hindi • Guard held with zebra skin Pg 5 TRAFFIC INDIA UPD • Customs officials seize Pg 6 ornamental fish at Coimbatore Airport • Five tonnes of Red Sanders logs Pg 7 • Experts link up to combat illegal Pg 5 seized at Gujarat port wildlife trade in Sri Lanka TRAFFIC ALER • Four tonnes of Sea cucumber Pg 7 seized in Tamil Nadu • Email alerts on CITES related Pg 6 SIGNPOST: Other significant Pg 12 OUTPOST issues now available by subscription news stories to read SIGNPOST Pg 10 NEW SECTION WILD CRY : Illegal wildlife trade threatens the future of many species in the © Ola Jennersten Ola © wild. This section highlights the plight of CITES one such species in trade. UPDATE • Tiger killers will be brought to Pg 6 book, says CITES Secretary General Pangolins in peril TRAFFIC POST march 2011 South Asia unites to curb illegal trade in endangered wildlife he eight countries of South Asia—India, Nepal, Pakistan, TAfghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives and Sri Lanka— joined forces and established the South Asia Wildlife Enforcement Network (SAWEN) to collaborate and co-operate on strengthening wildlife law enforcement in the region. -

NGO Directory

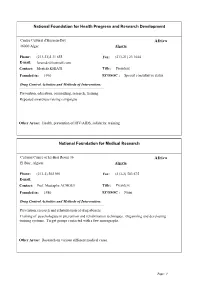

National Foundation for Health Progress and Research Development Centre Culturel d'Hussein-Day Africa 16000 Alger Algeria Phone: (213-21)2 31 655 Fax: (213-21) 23 1644 E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Mostefa KHIATI Title: President Founded in: 1990 ECOSOC : Special consultative status Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, counselling, research, training Repeated awareness raising campaigns Other Areas: Health, prevention of HIV/AIDS, solidarity, training National Foundation for Medical Research Cultural Centre of El-Biar Room 36 Africa El Biar, Algiers Algeria Phone: (213-2) 502 991 Fax: (213-2) 503 675 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Mustapha ACHOUI Title: President Founded in: 1980 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, research and rehabilitation of drug abusers. Training of psychologists in prevention and rehabilitation techniques. Organizing and developing training systems. Target groups contacted with a few monographs. Other Areas: Research on various different medical cases. Page: 1 Movimento Nacional Vida Livre M.N.V.L. Av. Comandante Valodia No. 283, 2. And.P.24. Africa C.P. 3969 Angola, Rep. Of Luanda Phone: (244-2) 443 887 Fax: E-mail: Contact: Dr. Celestino Samuel Miezi Title: National Director, Professor Founded in: 1989 ECOSOC : Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, treatment, counselling, rehabilitation, training, and criminology To combat drugs and its consequences through specialized psychotherapy and detoxification Other Areas: Health, psychotherapy, ergo therapy Maison Blanche (CERMA) 03 BP 1718 Africa Cotonou Benin Phone: (229) 300850/302816 Fax: (229) 30 04 26 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Rene Gilbert AHYI Title: President Founded in: 1988 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, treatment, training and education. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full