Final Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

Democracy in the Caribbean a Cause for Concern

DEMOCRACY IN THE CARIBBEAN A CAUSE FOR CONCERN Douglas Payne April 7, 1995 Policy Papers on the Americas Democracy in the Caribbean A Cause for Concern Douglas W. Payne Policy Papers on the Americas Volume VI Study 3 April 7, 1995 CSIS Americas Program The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), founded in 1962, is an independent, tax-exempt, public policy research institution based in Washington, DC. The mission of CSIS is to advance the understanding of emerging world issues in the areas of international economics, politics, security, and business. It does so by providing a strategic perspective to decision makers that is integrative in nature, international in scope, anticipatory in timing, and bipartisan in approach. The Center's commitment is to serve the common interests and values of the United States and other countries around the world that support representative government and the rule of law. * * * CSIS, as a public policy research institution, does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this report should be understood to be solely those of the authors. © 1995 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. This study was prepared under the aegis of the CSIS Policy Papers on the Americas series. Comments are welcome and should be directed to: Joyce Hoebing CSIS Americas Program 1800 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 Phone: (202) 775-3180 Fax: (202) 775-3199 Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................... -

1 Language Use, Language Change and Innovation In

LANGUAGE USE, LANGUAGE CHANGE AND INNOVATION IN NORTHERN BELIZE CONTACT SPANISH By OSMER EDER BALAM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support from many people, who have been instrumental since the inception of this seminal project on contact Spanish outcomes in Northern Belize. First and foremost, I am thankful to Dr. Mary Montavon and Prof. Usha Lakshmanan, who were of great inspiration to me at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. Thank you for always believing in me and motivating me to pursue a PhD. This achievement is in many ways also yours, as your educational ideologies have profoundly influenced me as a researcher and educator. I am indebted to my committee members, whose guidance and feedback were integral to this project. In particular, I am thankful to my adviser Dr. Gillian Lord, whose energy and investment in my education and research were vital for the completion of this dissertation. I am also grateful to Dr. Ana de Prada Pérez, whose assistance in the statistical analyses was invaluable to this project. I am thankful to my other committee members, Dr. Benjamin Hebblethwaite, Dr. Ratree Wayland, and Dr. Brent Henderson, for their valuable and insighful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to scholars who have directly or indirectly contributed to or inspired my work in Northern Belize. These researchers include: Usha Lakshmanan, Ad Backus, Jacqueline Toribio, Mark Sebba, Pieter Muysken, Penelope Gardner- Chloros, and Naomi Lapidus Shin. -

CONSTITUTION of BELIZE CONSTITUTIONAL CHRONOLOGY by Albert J

CONSTITUTION OF BELIZE CONSTITUTIONAL CHRONOLOGY by Albert J. Ysaguire 1978 On January 27, Premier Price rejected a proposed compromise with Guatemala whereby Belize would cede 300 square miles of mainland and 600 square miles of seabed in the south of Belize in return for Guatemala's recognition of Belize's Independence. A similar proposal by Britain for Belize to cede between 1000 an 2000 square miles of land and adjacent seabed was earlier rejected. Mr. Price announced on March 10 at a conference that Barbados, Guyana an Jamaica had agreed to take part in multilateral security arrangements that would defend the territorial integrity of an independent Belize. This agreement did not come into force since at the time Belize's Independence date could not be agreed upon. On May 18, the Gutemalan foreign minister, Señor Adolfo Molina Orantes said in a press interview that his government maintained its demand for a cession of territory by Belize. He insisted that the two governments set up a join military staff, consultations on Belize's external relations and economic integration into the Central American system. The British Permanent Representative at the U.N. announced on November 28 that a four- point proposal had been put to Guatemala to resolve the conflict with Belize. Development aid including help with construction of roads to facilitate Guatemala's access to the coast, free port in the Port of Belize and a revision of the seaward boundaries of the two countries to guarantee permanent access for Guatemala to the open sea. On December 7 the Guatemalan foreign minister, Señor Castillo Valdez announced that the British plan for the settlement of the dispute with Belize was unacceptable and that he would now deal directly with Belize. -

Water Operators' Partnership Case Study

Water Operators’ Partnership Case Study Global Water perators Partnerships Alliance Contra Costa Water District USA Belize Water Services Belize Water Operators’ Partnership Case Study BWS – Belize Water Services and CCWD – Contra Costa Water District Published in September 2016 Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) 2016 All rights reserved UN-HABITAT, P.O. Box 30030, GPO, Nairobi, 00100, KENYA Tel: +254 20 762 3120 (Central Office) www.unhabitat.org Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries regarding its economic system or degree of development. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), the United Nations and its member states. Acknowledgements The main author, Vincent Merme, is grateful to many kind people in Belize and California who helped in the preparation of this case study and provided documents. He wishes to express thanks especially to Alvan Haynes, BWS Chief Executive Officer, and Jerry Brown, CCWD General Manager. GWOPA knowledge management team and facilitators of this WOP receive special gratitude for their expert -

The Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of Southern Belize

Reports Submitted to FAMSI: Phillip J. Wanyerka The Southern Belize Epigraphic Project: The Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of Southern Belize Posted on December 1, 2003 1 The Southern Belize Epigraphic Project: The Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of Southern Belize Table of Contents Introduction The Glyphic Corpus of Lubaantún, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions The Ceramic Inscriptions The Glyphic Corpus of Nim LI Punit, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions Miscellaneous Sculpture The Glyphic Corpus of Xnaheb, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions Miscellaneous Sculpture The Glyphic Corpus of Pusilhá, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions The Sculptural Monuments Miscellaneous Texts and Sculpture The Glyphic Corpus of Uxbenka, Toledo District, Belize The Monumental Inscriptions Miscellaneous Texts Miscellaneous Sculpture Other Miscellaneous Monuments Tzimín Ché Stela 1 Caterino’s Ruin, Monument 1 Choco, Monument 1 Pearce Ruin, Phallic Monument The Pecked Monuments of Southern Belize The Lagarto Ruins Papayal The Cave Paintings Acknowledgments List of Figures References Cited Phillip J. Wanyerka Department of Anthropology Cleveland State University 2121 Euclid Avenue (CB 142) Cleveland, Ohio 44115-2214 p.wanyerka @csuohio.edu 2 The Southern Belize Epigraphic Project: The Hieroglyphic Inscriptions of Southern Belize Introduction The following report is the result of thirteen years of extensive and thorough epigraphic investigations of the hieroglyphic inscriptions of the Maya Mountains region of southern Belize. The carved monuments of the Toledo and Stann Creek Districts of southern Belize are perhaps one of the least understood corpuses in the entire Maya Lowlands and are best known today because of their unusual style of hieroglyphic syntax and iconographic themes. Recent archaeological and epigraphic evidence now suggests that this region may have played a critical role in the overall development, expansion, and decline of Classic Maya civilization (see Dunham et al. -

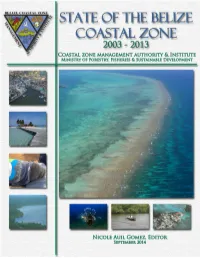

State of the Belize Coastal Zone Report 2003–2013

Cite as: Coastal Zone Management Authority & Institute (CZMAI). 2014. State of the Belize Coastal Zone Report 2003–2013. Cover Photo: Copyright Tony Rath / www.tonyrath.com All Rights Reserved Watermark Photos: Nicole Auil Gomez The reproduction of the publication for educational and sourcing purposes is authorized, with the recognition of intellectual property rights of the authors. Reproduction for commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. State of the Belize Coastal Zone 2003–2013 2 Coastal Zone Management Authority & Institute, 2014 Table of Contents Foreword by Honourable Lisel Alamilla, Minister of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 Foreword by Mr. Vincent Gillett, CEO, CZMAI ............................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................................. 7 Contributors ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Belize Election Law Marty Casado Mon, Dec 1, 2014 Government 0 8520

Belize Election Law Marty Casado Mon, Dec 1, 2014 Government 0 8520 Elections in Belize are the duly held elections held at various levels of government in the nation of Belize. Dissolving elected bodies is broken down in the following order:- The Legislature: Dissolving the National Assembly of Belize is the prerogative of the Governor General of Belize, currently Sir Colville Young. Under sections 84 and 85 of the Constitution, the Governor General can at any time dissolve or prorogue the Assembly under the advice of the Prime Minister of Belize, with the caveat that a general election must be called within three months of such dissolution, unless the Governor General sees no reason to do so. City and town councils: City and town councils dissolve on the last Sunday of February in every third year, with the election called for the first Wednesday in March in every third year. General elections: Belize elects on national level a legislature. The National Assembly has two chambers. The House of Representatives has 31 members, elected for a five-year term in single-seat constituencies as of 2008. The Senate has 12 members appointed for a five-year term. Belize has a two-party system, which means that there are two dominant political parties, with extreme difficulty for anybody to achieve electoral success under the banner of any other party. Only once in the most recent general elections did an independent candidate receive more votes than a party candidate. Wilfred Elrington, running independently in 2003, received twice as many votes as the UDP candidate but failed to win. -

Big Game, Small Town Clientelism and Democracy in the Modern Politics of Belize (1954 to 2011)

Big Game, Small Town Clientelism and Democracy in the Modern Politics of Belize (1954 to 2011) Dylan Gregory Vernon A thesis submitted to University College London in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Caribbean and Latin American Politics from the Institute of the Americas, University College London 2013 Declaration I, Dylan Gregory Vernon, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in my thesis. Dylan Gregory Vernon 2 Abstract Presenting Belize as an illustrative and critical case of clientelist democracy in the Commonwealth Caribbean, this thesis explores the origins of clientelist politics alongside the pre-independence birth of political parties, analyses its rapid expansion after independence in 1981 and assesses its implications for democratic governance. Based on qualitative research, including interviews with major political leaders, the thesis contends that, despite Belize’s positive post- colonial reputation for consolidating formal democracy, the concurrent expansion of clientelism, as both an electoral strategy and a mode of participation, ranks high among the worrying challenges affecting the quality of its democracy. Although intense party competition in a context of persistent poverty is central to explaining the trajectory of clientelism in Belize, the Westminster model of governance, the disappearance of substantive policy distinctions among parties and the embrace of neoliberal economic policies fuelled its expansion. Small- state size and multi-ethnicity have also been contributing factors. Even though the thousands of monthly dyadic transactions in constituencies are largely rational individual choices with short-term distributive benefits, the thesis concludes that, collectively, these practices lead to irrational governance behaviour and damaging macro-political consequences. -

The What and How of Boundary Redistricting 2004

THE WHAT AND HOW OF BOUNDARY REDISTRICTING 2004 By Myrtle Palacio What Is Boundary Redistricting? Boundary Redistricting and Boundary Delimitation are terminologies used interchangeably for the process of fixing, drawing, altering and/or increasing electoral boundaries. It is done to decrease substantial differences in the population ratio between electoral divisions. A new Electoral List compiled after Re-registration in 1998, demonstrated a difference in population ratio between the largest and smallest electoral divisions of 3.5 to 1. By September 2003, the gap widened to 4.4 to 1. The growth of the Electoral Roll at September 2003 is evidence that ten Electoral Divisions have grown by 25% or more. Five of these Electoral Divisions are in the Belize District namely, Lake Independence, Queen's Square, Belize Rural South, Pickstock and Port Loyola, in descending order. Of the remaining five, one is the Orange Walk South Division, and all four Electoral Divisions in the Cayo District. Boundary Redistricting is most commonly associated with majority electoral systems as ours. Success at the polls in the First Past the Post Electoral System (FPP) relies on garnering a majority number of single member constituencies. Did This Happen Before? The last Boundary Redistricting exercise was conducted in 2002. Then, all communities located in the Stann Creek District that were placed in the Toledo East Electoral Division in 1997, were transferred to the Stann Creek West Electoral Division. The ultimate effect was the redrawing or adjusting of the boundaries of 2 Electoral Divisions — Toledo East and Stann Creek West. The communities affected included the villages of Independence and Placencia. -

Giuseppe Troccoli Phd Thesis

BUILDING BELIZE CITY: AUTONOMY, SKILL AND MOBILITY AMONGST BELIZEAN AND CENTRAL AMERICAN CONSTRUCTION WORKERS Giuseppe Troccoli A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2019 Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this thesis: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/17441 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Giuseppe Troccoli This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. 2 Candidate's declaration I, Giuseppe Troccoli, do hereby certify that this thesis, submitted for the degree of PhD, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for any degree. I was admitted as a research student at the University of St Andrews in September 2014. I received funding from an organisation or institution and have acknowledged the funder(s) in the full text of my thesis. Date Signature of candidate Supervisor's declaration I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

2021 Live and Invest in Belize Manual

Live and Invest in Belize 2021 Live and Invest in Belize By the Editors of Live and Invest Overseas™ Published by Live and Invest Overseas™ Calle Dr. Alberto Navarro, Casa No. 45, El Cangrejo, Panama, Republic of Panama Publisher: Kathleen Peddicord Copyright © 2021 Live and Invest Overseas™. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without the express written consent of the publisher. The information contained herein is obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Any investments recommended in this publication should be made only after consulting with your investment advisor and only after reviewing the prospectus or financial statements of the company. Copyright © 2021 Live and Invest Overseas™ Live and Invest in Belize 2021 Content Welcome to Belize ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 Geography ................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Climate ...................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Flora and fauna ........................................................................................................................................................