Giuseppe Troccoli Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unions Rally at Memorial Park GOB Tables New Proposals to Unions

Tuesday, May 11, 2021 AMANDALABelize Page 1 NO. 3459 BELIZE CITY, TUESDAY, MAY 11, 2021 (16 PAGES) $1.00 Bondholders and GoB, no deal yet BELIZE CITY. Mon. May 10, 2021 Last week, a meeting scheduled between holders of Belize’s Super- GOB tables new bond and the Minister of State in the Ministry of Finance, Chris Coye, was proposals to unions canceled after the Creditor Committee’s representatives BELIZE CITY, Mon. May 10, 2021 indicated that the meeting would be A meeting between the Joint fruitless if Belize refuses to sign on Unions Negotiating Team and the to an IMF support plan. Government of Belize officials ended Please turn toPage 15 Please turn toPage 15 Abusive relationship ends in fatal arson by Dayne Guy St. Matthews Village, Cayo District, Mon, May 10, 2021 A mother and her 3-year-old son were reportedly burned to death in the village of St. Matthews when their home was set on fire. Her ex- common law husband is the prime suspect. According to police reports, this heinous act of arson-turned-murder occurred sometime before 11:00 o’clock on Friday night. The house of 36-year-old Kendra Middleton PM gets the jab was burnt to the ground, while she and her three-year-old child, Aiden Perez, were inside. They both perished. Unions rally at Memorial Park When firefighters arrived at the scene, the blaze had already Please turn toPage 14 Former George Street boss’s son murdered BELIZE CITY, Mon. May 10, 2021 organized resistance to salary cuts in by Dayne Guy On Friday, May 7, the members of the public sector. -

26Th March 2015, in the National Assembly Chamber, !Belmopan, at 10:18 AM

!1 BELIZE ! No. HR26/1/11 ! HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES! th Thursday, 26 ! March, 2015 10:18! A.M ------! Pursuant to the Direction of Mr. Speaker on the 15th March 2015, the House met on Thursday, 26th March 2015, in the National Assembly Chamber, !Belmopan, at 10:18 AM. ! ! Members Present: The Hon. Michael Peyrefitte, Speaker The Hon. Dean O. Barrow (Queen’s Square), Prime Minister, Minister of Finance and Economic Development The Hon. Gaspar Vega (Orange Walk North), Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Natural Resources and Agriculture The Hon. Erwin R. Contreras (Cayo West), Minister of Trade, Investment Promotion, Private Sector Development and Consumer Protection The Hon. Patrick J. Faber (Collet), Minister of Education, Youth and Sports The Hon. Manuel Heredia Jr. (Belize Rural South), Minister of Tourism and Culture The Hon. Anthony Martinez (Port Loyola), Minister of Human Development, Social Transformation and Poverty Alleviation The Hon. John Saldivar (Belmopan), Minister of National Security The Hon. Wilfred P. Elrington (Pickstock), Attorney General and Minister of Foreign Affairs The Hon. Rene Montero (Cayo Central), Minister of Works and Transport The Hon. Pablo S. Marin (Corozal Bay), Minister of Health The Hon. Santino Castillo (Caribbean Shores), Minister of State in the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development The Hon. Hugo Patt (Corozal North), Minister of State in the Ministry of Natural Resources and Agriculture The Hon. Herman Longsworth (Albert), Minister of State in the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports The Hon. Mark King (Lake Independence), Minister of State in the Ministry of Human Development, Social Transformation and Poverty Alleviation The Hon. -

Budget Debate

BELIZE No. HR19/1/12 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES nd Thursday, 22 March 2018 10:24 A.M. ---*--- Pursuant to the Order of the House on the 9th March 2018, the House met on Thursday, 22nd March 2018, in the National Assembly Chamber, Belmopan, at 10:24 A.M. Members Present: The Hon. Laura Tucker-Longsworth, Speaker The Rt. Hon. Dean O. Barrow (Queen’s Square) Prime Minister, Minister of Finance and Natural Resources The Hon. Patrick J. Faber (Collet), Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Education, Culture, Youth and Sports The Hon. Erwin R. Contreras (Cayo West), Minister of Economic Development, Petroleum, Investment, Trade and Commerce The Hon. John Saldivar (Belmopan), Minister of National Security The Hon. Michael Finnegan (Mesopotamia), Minister of Housing and Urban Development The Hon. Anthony Martinez (Port Loyola), Minister of Human Development, Social Transformation and Poverty Alleviation The Hon. Manuel Heredia Jr. (Belize Rural South), Minister of Tourism and Civil Aviation The Hon. Rene Montero (Cayo Central), Minister of Works The Hon. Wilfred P. Elrington (Pickstock), Minister of Foreign Affairs The Hon. Pablo S. Marin (Corozal Bay), Minister of Health The Hon. Hugo Patt (Corozal North), Minister of Local Government, Labour, Rural Development, Public Service, Energy and Public Utilities The Hon. Edmond G. Castro (Belize Rural North), Minister of Transport and NEMO The Hon. Dr. Omar Figueroa (Cayo North), Minister of State in the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries, the Environment and Sustainable Development and Immigration and Deputy Speaker The Hon. Frank Mena (Dangriga), Minister of State in the Ministry of Public Service, Energy and Public Utilities The Hon. -

BELIZE No. HR 26/1/11 HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES

BELIZE No. HR 26/1/11 ! HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Thursday, 26th March 2015 ! 10:18 AM. ---*---! Pursuant to the Order of the House on the 13th March 2015, the House met on Thursday, 26th March 2015, in the National Assembly Chamber, Belmopan, at 10:18 AM. ------! ! Members Present: The Hon. Michael Peyrefitte, Speaker The Hon. Dean O. Barrow (Queen’s Square), Prime Minister, Minister of Finance and Economic Development The Hon. Gaspar Vega (Orange Walk North), Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Natural Resources and Agriculture The Hon. Erwin R. Contreras (Cayo West), Minister of Trade, Investment Promotion, Private Sector Development and Consumer Protection The Hon. Patrick J. Faber (Collet), Minister of Education, Youth and Sports The Hon. Manuel Heredia Jr. (Belize Rural South), Minister of Tourism and Culture The Hon. Anthony Martinez (Port Loyola), Minister of Human Development, Social Transformation and Poverty Alleviation The Hon. John Saldivar (Belmopan), Minister of National Security The Hon. Wilfred P. Elrington (Pickstock), Attorney General and Minister of Foreign Affairs The Hon. Pablo S. Marin (Corozal Bay), Minister of Health The Hon. Rene Montero (Cayo Central), Minister of Works and Transport The Hon. Edmond G. Castro (Belize Rural North), Minister of State in the Ministry of Works and Transport, Deputy Speaker The Hon. Santino Castillo (Caribbean Shores), Minister of State in the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development The Hon. Hugo Patt (Corozal North), Minister of State in the Ministry of Natural Resources and Agriculture The Hon. Herman Longsworth (Albert), Minister of State in the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports The Hon. Mark King (Lake Independence), Minister of State in the Ministry of Human Development, Social Transformation and Poverty Alleviation The Hon. -

Ccs Blz En.Pdf

BCCS 2/18/09 10:31 AM Page 1 BCCS 2/18/09 10:31 AM Page 2 BCCS 2/18/09 10:31 AM Page 3 BCCS 2/18/09 10:31 AM Page 4 BELIZE COUNTRY COOPERATION STRATEGY 2008–2011 Photo courtesy Ministry of Health of Belize A Mennonite farmer receives rubella vaccine, 2004. BCCS 2/18/09 10:31 AM Page 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11 FOREWORD 15 1. INTRODUCTION 16 2. COUNTRY HEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT CHALLENGES AND NATIONAL RESPONSE 18 2.1 General context 18 2.2 Health status of the population 19 2.3 Major health problems 20 2.4 Health determinants 26 2.5 Health sector policies and organization 31 2.6 The Millennium Development Goals 37 2.7 Key health priorities and challenges 37 2.8 Opportunities and strengths 38 3. DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AND PARTNERSHIPS: TECHNICAL COOPERATION, AID EFFECTIVENESS, AND COORDINATION 39 3.1 Key international aid and partners in health 39 3.2 National ownership 42 3.3 Alignment and harmonization 42 3.4 Challenges 42 3.5 Opportunities 42 4. PAST AND CURRENT PAHO/WHO COOPERATION 43 4.1 Cooperation overview 43 4.2 Structure and ways of working 45 4.3 Resources 46 4.4 SWOT analysis of PAHO/WHO 48 5. STRATEGIC AGENDA FOR PAHO/WHO’S COOPERATION 49 5.1 Strategic priority 1: improving the health status of the population 50 5.2 Strategic priority 2: addressing key health determinants 54 5.3 Strategic priority 3: strengthening health sector policies and organization 56 5.4 Strategic priority 4: enhancing PAHO/WHO’s response 59 6. -

Capital Weekly 001 Colour.Pmd

Sunday, January 16, 2011 Capital Weekly Page 1 No. 001 Capital Sunday, Januar Weeklyy 16, 2011 Price: $1.00 From the Heart of the Nation to the Soul of the People No. 001 Sunday, January 16, 2011 Price: $1.00 NotNot AA RedRed CentCent ForFor TheThe WhitedWhited Sepulchre!Sepulchre! GOB will Continue to Resist Paying Arbitration Award s the old year will continue now to do so, came to an end, certain in the knowledge that ABelizeans were re- this is a campaign of, by, and minded of the enormous cost for, the people. an entire nation is being forced Mr Barrow was, in effect, to pay as a result of the irre- answering the question raised sponsible actions of a few un- in the local media as to whether principled and unpatriotic poli- or not his government would ticians, those who led the last be appealing this latest ruling administration. on the matter by the retiring Su- The painful reminder came preme Court Judge. The an- in the form of a judgement swer, of course, is an emphatic handed down by retiring Su- “YES!” preme Court Justice John Further expounding on his Lord Michael Ashcroft, Muria upholding an arbitartion Prime Minister Dean Barrow government’s decision to ap- Defending the Interest of the Modern-day Slave Master and award of $ 43 Million which a Belizean People Enemy of the Belizean People peal, Prime Minister Barrow London Tribunal Court had told Channel Seven News last ordered the Belize Govern- Message, the Prime Minister paying their just taxes to Be- Wednesday, “We are going to ment to pay the British Carib- stated,“This award was in lize. -

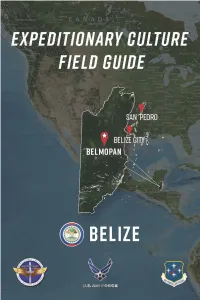

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

Belize 2020 Human Rights Report

BELIZE 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Belize is a constitutional parliamentary democracy. In the most recent national election, held on November 11, the People’s United Party won 26 of 31 seats in the National Assembly. Party leader John Briceno was sworn in as prime minister on November 12. The Ministry of National Security is responsible for oversight of police, prisons, the coast guard, and the military. The Belize Police Department is primarily responsible for internal security. The small military force primarily focuses on external security but also provides limited domestic security support to civilian authorities and has limited powers of arrest that are executed by the Belize Defence Force for land and shoreline areas and by the Coast Guard for coastal and maritime areas. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of security forces committed few abuses. Significant human rights issues included: allegations of the use of excessive force and inhuman treatment by security officers, allegations of widespread corruption and impunity by government officials, trafficking in persons, and child labor. In some cases the government took steps to prosecute public officials who committed abuses, both administratively and through the courts, but there were few successful prosecutions. Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from: a. Arbitrary Deprivation of Life and Other Unlawful or Politically Motivated Killings There was a report that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. A team from the branch of the security force responsible for a killing or other abuse investigates the allegation and then presents the findings, recommendations, and penalties to authorities. -

New Year- New Mandate

Wednesday, January 6, 2016 Capital Weekly Page 1 No. 044 Wednesday, January 6, 2016 Online Publication NEW YEAR- NEW MANDATE Extraordinaryhankful, Truthful, and thatOpportunity we see our way clear - Extraordinary Results Realistic, Reassur- to another successful year.” ing and Optimistic Speaking candidly of – that is how we must the challenges, he informs Tsummarize and characterize that the reduction in PetroCa- Prime Minister Dean Barrow’s ribe flows is perhaps the most New Year’s Message for 2016. pronounced, and that this The Prime Minister combined with the dizzying starts out recounting the na- fall in oil prices, we expect to tion’s blessings in 2015, having get much less from these Ven- been spared from hurricanes ezuela loan funds than we did and social upheaval, and hav- in 2015. In fact, he noted, the ing as he puts it, “steered our 2015 intake was already only way through the complexi- half of 2014. “This, combined ties of the relationship with with the drying up of earn- Guatemala; and politically we ings from our own petroleum capped everything with the exports, will put a severe crimp peaceful and historic gen- in Government revenues,” the eral elections of November.” Prime Minister admits. It is be- Turning to economics, cause of this, the fact that pay- the Prime Minister notes that ments on the Superbond will despite the challenges pre- have to be stepped up, and the sented by disease and the long inevitability of the Compensa- drought, which played havoc tion Award for the acquisition with shrimp and grains, and an of vital public utilities, that earlier than expected decrease the Government has had to in the export price of sugar, the raise the duty on fuel imports, productive sector performed the Prime Minister explains. -

Democracy in the Caribbean a Cause for Concern

DEMOCRACY IN THE CARIBBEAN A CAUSE FOR CONCERN Douglas Payne April 7, 1995 Policy Papers on the Americas Democracy in the Caribbean A Cause for Concern Douglas W. Payne Policy Papers on the Americas Volume VI Study 3 April 7, 1995 CSIS Americas Program The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), founded in 1962, is an independent, tax-exempt, public policy research institution based in Washington, DC. The mission of CSIS is to advance the understanding of emerging world issues in the areas of international economics, politics, security, and business. It does so by providing a strategic perspective to decision makers that is integrative in nature, international in scope, anticipatory in timing, and bipartisan in approach. The Center's commitment is to serve the common interests and values of the United States and other countries around the world that support representative government and the rule of law. * * * CSIS, as a public policy research institution, does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this report should be understood to be solely those of the authors. © 1995 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. This study was prepared under the aegis of the CSIS Policy Papers on the Americas series. Comments are welcome and should be directed to: Joyce Hoebing CSIS Americas Program 1800 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 Phone: (202) 775-3180 Fax: (202) 775-3199 Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................... -

1 Language Use, Language Change and Innovation In

LANGUAGE USE, LANGUAGE CHANGE AND INNOVATION IN NORTHERN BELIZE CONTACT SPANISH By OSMER EDER BALAM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support from many people, who have been instrumental since the inception of this seminal project on contact Spanish outcomes in Northern Belize. First and foremost, I am thankful to Dr. Mary Montavon and Prof. Usha Lakshmanan, who were of great inspiration to me at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. Thank you for always believing in me and motivating me to pursue a PhD. This achievement is in many ways also yours, as your educational ideologies have profoundly influenced me as a researcher and educator. I am indebted to my committee members, whose guidance and feedback were integral to this project. In particular, I am thankful to my adviser Dr. Gillian Lord, whose energy and investment in my education and research were vital for the completion of this dissertation. I am also grateful to Dr. Ana de Prada Pérez, whose assistance in the statistical analyses was invaluable to this project. I am thankful to my other committee members, Dr. Benjamin Hebblethwaite, Dr. Ratree Wayland, and Dr. Brent Henderson, for their valuable and insighful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to scholars who have directly or indirectly contributed to or inspired my work in Northern Belize. These researchers include: Usha Lakshmanan, Ad Backus, Jacqueline Toribio, Mark Sebba, Pieter Muysken, Penelope Gardner- Chloros, and Naomi Lapidus Shin. -

13Th November 2015

!BELIZE !No. HR1/1/12 ! HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES! th Friday, 13 November! 2015 ! 10:00 AM. Pursuant to a Proclamation of His Excellency the Governor-General, dated the 12th day of November 2015, appointing the day for the holding of a Session of the Legislature, the House met at 10:00 in the forenoon at the Grounds of the National Assembly Building, ! Belmopan. ---**---! CLERK: Good morning everyone. Let us all stand during the reading of the Proclamation. A Proclamation appointing a day for holding a Session of the National Assembly by His Excellency Sir Colville N. Young, G.C.M.G., M.B.E.,! Ph. D., J.P. (S), Governor General of Belize. WHEREAS, section 83 of the Belize Constitution provides, inter alia, that there shall be a session of the National Assembly at least once in every year, and that such session shall be held at such place within Belize and shall begin at such time as the Governor-General shall appoint by proclamation published in the !Gazette; AND WHEREAS, the said section 83 further provides that the first sitting of each House after the National Assembly has at any time been prorogued or !dissolved shall begin at the same time; AND WHEREAS, the National Assembly was dissolved with effect from 28th September 2015, and a general election of the Members of the House of th !Representatives was held on the 4 November 2015; NOW, THEREFORE, I, Colville Norbert Young, Knight Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Governor-General, in exercise of the powers conferred upon me by the abovementioned provisions of the Constitution, do hereby proclaim that a session of the National Assembly shall be held in front of the National Assembly Building, Belmopan, on Friday, the 13th November 2015; and that the first sitting of the House of Representatives and of the Senate will be held at the said venue commencing at 10:00 o’clock in !the forenoon.