Wangka Maya, the Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre Janet Sharp and Nick Thieberger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martu Aboriginal People's Uses and Knowledge of Their

To hunt and to hold: Martu Aboriginal people’s uses and knowledge of their country, with implications for co-management in Karlamilyi (Rudall River) National Park and the Great Sandy Desert, Western Australia Fiona J. Walsh, B.Sc. (Zoology), M.Sc. Prelim. (Botany) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social and Cultural Studies (Anthropology) and School of Plant Biology (Ecology) 2008 i Photo i (title page) Rita Milangka displays Lil-lilpa (Fimbristylis eremophila), the UWA Department of Botany field research vehicle is in background. This sedge has numerous small seeds that were ground into an edible paste. Whilst Martu did not consume sedge and grass seeds in contemporary times, their use was demonstrated to younger people and visitors. ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Dianne and John Walsh. My mother cultivated my joy in plants and wildlife. She introduced me to my first bush foods (including kurarra, kogla, ‘honeysuckle’, bardi grubs) on Murchison lands inhabited by Yamatji people then my European pastoralist forbearers.1 My father shares bush skills, a love of learning and long stories. He provided his Toyota vehicle and field support to me on Martu country in 1988. The dedication is also to Martu yakurti (mothers) and mama (fathers) who returned to custodial lands to make safe homes for children and their grandparents and to hold their country for those past and future generations. Photo ii John, Dianne and Melissa Walsh (right to left) net for Gilgie (Freshwater crayfish) on Murrum in the Murchison. -

Extract from the National Native Title Register

Extract from the National Native Title Register Determination Information: Determination Reference: Federal Court Number(s): WAD6110/1998 WAD77/2006 WAD141/2010 NNTT Number: WCD2013/002 Determination Name: Martu (Part B), Karnapyrri, and Martu #2 Date(s) of Effect: 16/05/2013 Determination Outcome: Native title exists in the entire determination area Register Extract (pursuant to s. 193 of the Native Title Act 1993) Determination Date: 16/05/2013 Determining Body: Federal Court of Australia ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: Not Applicable REGISTERED NATIVE TITLE BODY CORPORATE: Western Desert Lands Aboriginal Corporation (Jamukurnu- Yapalikunu) RNTBC Trustee Body Corporate PO Box 331 WEST PERTH Western Australia 6872 Note: current contact details for the Registered Native Title Body Corporate are available from the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations www.oric.gov.au COMMON LAW HOLDER(S) OF NATIVE TITLE: SCHEDULE FOUR - NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS Part One 1. In respect of the whole of the Determination Area, except for the parts described in Part Two below, the persons referred to in paragraph 2(a) are those people known as the Martu People. The Martu People are those Aboriginal people who hold in common the body of traditional law and culture governing the Determination Area and who identify as Martu and who, in accordance with their traditional laws and customs, identify themselves as being members of one, some or all of the following language groups: National Native Title Tribunal Page 1 of 9 Extract from the National Native Title Register WCD2013/002 (a) Manyjilyjarra; (b) Kartujarra; (c) Kiyajarra; (d) Putijarra; (e) Nyiyaparli; (f) Warnman; (g) Ngulipartu; (h) Pitjikala; (i) Karajarra; (j) Jiwaliny; (k) Mangala; and (l) Nangajarra. -

Martu Paint Country

MARTU PAINT COUNTRY THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF COLOUR AND AESTHETICS IN WESTERN DESERT ROCK ART AND CONTEMPORARY ACRYLIC ART Samantha Higgs June 2016 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University Copyright by Samantha Higgs 2016 All Rights Reserved Martu Paint Country This PhD research was funded as part of an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project, the Canning Stock Route (Rock art and Jukurrpa) Project, which involved the ARC, the Australian National University (ANU), the Western Australian (WA) Department of Indigenous Affairs (DIA), the Department of Environment and Climate Change WA (DEC), The Federal Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA, now the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Population and Communities) the Kimberley Land Council (KLC), Landgate WA, the Central Desert Native Title Service (CDNTS) and Jo McDonald Cultural Heritage Management Pty Ltd (JMcD CHM). Principal researchers on the project were Dr Jo McDonald and Dr Peter Veth. The rock art used in this study was recorded by a team of people as part of the Canning Stock Route project field trips in 2008, 2009 and 2010. The rock art recording team was led by Jo McDonald and her categories for recording were used. I certify that this thesis is my own original work. Samantha Higgs Image on title page from a painting by Mulyatingki Marney, Martumili Artists. Martu Paint Country Acknowledgements Thank you to the artists and staff at Martumili Artists for their amazing generosity and patience. -

WA Health Language Services Policy

WA Health Language Services Policy September 2011 Cultural Diversity Unit Public Health Division WA Health Language Services Policy Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Government policy obligations ................................................................................................... 2 2. Policy goals and aims .................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Scope......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Guiding principles ............................................................................................................................................. 6 5. Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 6. Provision of interpreting and translating services .................................................................... -

Making the Journey

Making the Journey Arts and disability in Australia Mary Hutchison © 2005 Arts Access Australia Designed by Boccalatte Printed in Australia by Lamb Printers Pty Ltd Arts Access Australia c/— Accessible Arts Pier 4, The Wharf, Hickson Rd Walsh Bay, NSW 2000, Australia National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Hutchison, Mary Making the journey: arts and disability in Australia ISBN 097513 230 X 1. People with disabilities and the arts — Australia. 2. People with disabilities and the performing arts — Australia. 3. People with disabilities — Education — Australia. I. Arts Access Australia. II. Title. 790.196 This book is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owner. Neither may information be stored electronically in any form whatsoever without such permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. Front cover photo: Ensemble members of the Back to Back Theatre production Mental: Rita Halabarec, Mark Deans, Darren Riches and Sonia Teuben. (Not pictured: Nicki Holland.) Photograph by Jeff Busby. Making the Journey Arts and disability in Australia Mary Hutchison In many areas of Indigenous Australia it is considered offensive to publish photographs or the names of Aboriginal people who have recently died. Readers are warned that this book may inadvertently contain such names or pictures. Foreword Department of Family and Community Services The Howard Government is pleased to Support is delivered by several Australian endorse activities celebrating the ability Government Departments, as well as state of people with disability and which and territory services receiving Howard remove barriers to their full participation Government funding to provide a range of in the community. -

Revealed Catalogue 2008

R e v e a l e d Cover image: Karnti Season (Bush Potato Season) Eva Nargoodah, Mangkaja Arts Photo: Tim Acker R e v e a l e d Emerging Artists from Western Australia’s Aboriginal Art Centres 25 October - 15 November, 2008 Revealed is presented in association with the Government of Western Australia’s Department of Culture and the Arts and the Department of Industry and Resources Message from the Government of Western Australia Hon. Troy Buswell MLA John Day MLA Treasurer; Minister for Commerce; Science and Innovation Minister of Culture and the Arts Aboriginal art provides Australia with an iconic and recognisable national and The Western Australian State Government is committed to the development of this international identity. Aboriginal art is one of the most important means for Aboriginal important arts sector. people, particularly those in remote areas, to participate in mainstream economic systems, which also provides contemporary relevance for maintaining the cultural Indigenous cultural expression is essential to the unique culture of Western Australia integrity that drives the industry. and celebrated world-wide. The Aboriginal Economic Development Division within the Department of Industry It is an industry which tends to focus on the successful works of elderly artists, often and Resources (DoIR) is the Western Australian Government’s key agency for distracting attention from the emerging artists in each region. support and advice to Aboriginal enterprise development. Revealed is an important partnership between the Department of Culture and the Arts In response to the identified need for a strategic approach to supporting esternW and the Aboriginal Economic Development Division of the Department of Industry and Australian’s most significant visual arts industry, DoIR developed the Arts Resources, and Central TAFE. -

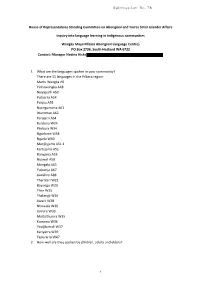

Submission No.78

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Inquiry into language learning in Indigenous communities Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre} PO Box 2736, South Hedland WA 6722 Contact: Manager Nadine Hicks 1. What are the languages spoken in your community? There are 31 languages in the Pilbara region: Martu Wangka A6 Yinhawangka A48 Nyiyaparli A50 Putijarra A54 Palyku A55 Nyangumarta A61 Warnman A62 Karajarri A64 Burduna W24 Pinikura W34 Ngarluma W38 Ngarla W40 Manjilyjarra A51.1 Kartujarra A51 Banyjima A53 Nyamal A58 Mangala A65 Yulparija A67 Juwaliny A88 Tharrkari W21 Bayungu W23 Thiin W25 Thalanyji W26 Jiwarli W28 Nhuwala W30 Jurruru W33 Martuthunira W35 Kurrama W36 Yindjibarndi W37 Kariyarra W39 Yapurarra W47 2. How well are they spoken by children, adults and elders? 1 This varies widely. While some languages such as Thiin are no longer spoken at all, others such as Martu Wangka are widely spoken by all age groups. Detailed information for each language is available on request. 3. Describe your group and project? Wangka Maya was begun by a group of Pilbara language speakers who were concerned at the loss of languages. It aims to record and foster the Aboriginal languages of the Pilbara region. The group began with no funding working as volunteers. Gradually they attracted project funding and eventually ongoing funding as a language centre. a) Why was it important to start up? Almost no work was being done to record or foster the use of local languages. b) How long have you been running? Since 1987 c) What age group(s) are you working with? All ages. -

Res Urces Catal

urces Res Catal gue 264 Hannan Street (08) 9021 3788 www.wangka.com.au New Language Desk Plaques $50.00 Language plaques are 30cm x 30cm in size and come in these languages; Kaalamaya, Ngaanyatjarra, Ngajumaya, Tjupan, Mirning, Cundeelee Wangka, Kuwarra, Ngalia and Wangkatja. 6 Piece Coaster Set $10.00 6 piece coaster set featuring Aboriginal bush foods such as the Honey Ant, Karlkurla and other yummy foods. Light weight material, perfect for posting. Childrens Books Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre has a variety of resources, please see price list at back of catalouge. If you are interested in any of the following resources please come and visit us at 264 Hannan Street. Books Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre has a variety of resources, please see price list at back of catalouge. If you are interested in any of the following resources please come and visit us at 264 Hannan Street. Books Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre has a variety of resources, please see price list at back of catalouge. If you are interested in any of the following resources please come and visit us at 264 Hannan Street. Learning resources Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre has a variety of resources, please see price list at back of catalouge. If you are interested in any of the following resources please come and visit us at 264 Hannan Street. Learning resources Price List Titles A - D A Town is Born: Fitzroy Crossing $40 AIATSIS Map, small $30 Alphabet and syllables charts- each language $10 Art and Songs from the Spinifex People $20 Australian -

Phonotactics in Historical Linguistics: Quantitative Interrogation of a Novel Data Source

Phonotactics in historical linguistics: Quantitative interrogation of a novel data source Jayden Macklin-Cordes BA (Hons) 0000-0003-1910-3969 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2021 School of Languages and Cultures Abstract Historical linguistics has been uncovering historical patterns of shared linguistic descent with consid- erable success for nearly two centuries. In recent decades, historical linguistics has been augmented with quantitative phylogenetic methods, increasing the scope and scale of linguistic phylogenetic trees that can be inferred and, by extension, the kinds of historical questions that can be investigated. Throughout this period of rapid methodological development, lexical cognate data has remained the main currency of interest. However, there is an immense array of structural variation throughout the world’s languages—the outcome of thousands of years of linguistic evolution—raising the prospect of additional sources of historical signal which could help infer shared linguistic pasts. This thesis investigates the prospect of making linguistic phylogenetic inferences using quantitative phonotactic data, semi-automatically extracted from wordlists. The primary research question moti- vating the study is as follows. Can a linguistic phylogeny be inferred with greater confidence when lexical cognate data is combined with phonotactic data? Underlying this is the more general question of how to approach and evaluate novel empirical data sources in linguistic phylogenetic research. I begin with a literature review, situating current linguistic phylogenetic research within historical linguistics broadly and elucidating the motivations for looking further into phonotactics as a data source. I also introduce Australian languages and their phonological profiles, as these provide the language sample for the rest of the thesis. -

Registration Test Template

Registration test decision Application name Gingirana Name of applicant Billy Atkins, Miriam Atkins, Slim Williams, Anthony Charles , Kate George, Stan Hill, NNTT file no. WC2006/002 Federal Court of Australia file no. WAD6002/2003 Date application made 9 May 2003 Date application last amended 23 July 2013 I have considered this claim for registration against each of the conditions contained in ss. 190B and 190C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth). On 6 September 2013, I decided that the claim satisfies each of the conditions contained in ss. 190B and C and I accept this claim for registration pursuant to s. 190A(6) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth). This is a statement of my reasons for that decision. Date of decision: 29 October 2013 ___________________________________ Susan Walsh [Delegate of the Native Title Registrar pursuant to sections 190, 190A, 190B, 190C, 190D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth) under an instrument of delegation dated 30 July 2013 and made pursuant to s. 99 of the Act.] Shared Country, shared future. Introduction [1] This document sets out my reasons, as the Registrar’s delegate, for the decision to accept the claim made in the Gingirana application (the claim) for registration pursuant to s. 190A(6) of the Act. I note that all references in these reasons to legislative sections refer to the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth) which I shall call ‘the Act’, as in force on the day this decision is made, unless otherwise specified. Please refer to the Act for the exact wording of each condition. -

National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005

National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 Report submitted to the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in association with the Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Front cover photo: Yipirinya School Choir, Northern Territory. Photo by Faith Baisden Disclaimer The Commonwealth, its employees, officers and agents are not responsible for the activities of organisations and agencies listed in this report and do not accept any liability for the results of any action taken in reliance upon, or based on or in connection with this report. To the extent legally possible, the Commonwealth, its employees, officers and agents, disclaim all liability arising by reason of any breach of any duty in tort (including negligence and negligent misstatement) or as a result of any errors and omissions contained in this document. The views expressed in this report and organisations and agencies listed do not have the endorsement of the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts (DCITA). ISBN 0 642753 229 © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Attorney-General’s Department Robert Garran Offices National Circuit CANBERRA ACT 2600 Or visit http://www.ag.gov.au/cca This report was commissioned by the former Broadcasting, Languages and Arts and Culture Branch of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services (ATSIS). -

AIATSIS Lan Ngua Ge T Hesaurus

AIATSIS Language Thesauurus November 2017 About AIATSIS – www.aiatsis.gov.au The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) is the world’s leading research, collecting and publishing organisation in Australian Indigenous studies. We are a network of council and committees, members, staff and other stakeholders working in partnership with Indigenous Australians to carry out activities that acknowledge, affirm and raise awareness of Australian Indigenous cultures and histories, in all their richness and diversity. AIATSIS develops, maintains and preserves well documented archives and collections and by maximising access to these, particularly by Indigenous peoples, in keeping with appropriate cultural and ethical practices. AIATSIS Thesaurus - Copyright Statement "This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use within your organisation. All other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to The Library Director, The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601." AIATSIS Language Thesaurus Introduction The AIATSIS thesauri have been made available to assist libraries, keeping places and Indigenous knowledge centres in indexing / cataloguing their collections using the most appropriate terms. This is also in accord with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Research Network (ATSILIRN) Protocols - http://aiatsis.gov.au/atsilirn/protocols.php Protocol 4.1 states: “Develop, implement and use a national thesaurus for describing documentation relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and issues” We trust that the AIATSIS Thesauri will serve to assist in this task.