Martine's Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martu Aboriginal People's Uses and Knowledge of Their

To hunt and to hold: Martu Aboriginal people’s uses and knowledge of their country, with implications for co-management in Karlamilyi (Rudall River) National Park and the Great Sandy Desert, Western Australia Fiona J. Walsh, B.Sc. (Zoology), M.Sc. Prelim. (Botany) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social and Cultural Studies (Anthropology) and School of Plant Biology (Ecology) 2008 i Photo i (title page) Rita Milangka displays Lil-lilpa (Fimbristylis eremophila), the UWA Department of Botany field research vehicle is in background. This sedge has numerous small seeds that were ground into an edible paste. Whilst Martu did not consume sedge and grass seeds in contemporary times, their use was demonstrated to younger people and visitors. ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Dianne and John Walsh. My mother cultivated my joy in plants and wildlife. She introduced me to my first bush foods (including kurarra, kogla, ‘honeysuckle’, bardi grubs) on Murchison lands inhabited by Yamatji people then my European pastoralist forbearers.1 My father shares bush skills, a love of learning and long stories. He provided his Toyota vehicle and field support to me on Martu country in 1988. The dedication is also to Martu yakurti (mothers) and mama (fathers) who returned to custodial lands to make safe homes for children and their grandparents and to hold their country for those past and future generations. Photo ii John, Dianne and Melissa Walsh (right to left) net for Gilgie (Freshwater crayfish) on Murrum in the Murchison. -

Extract from the National Native Title Register

Extract from the National Native Title Register Determination Information: Determination Reference: Federal Court Number(s): WAD6110/1998 WAD77/2006 WAD141/2010 NNTT Number: WCD2013/002 Determination Name: Martu (Part B), Karnapyrri, and Martu #2 Date(s) of Effect: 16/05/2013 Determination Outcome: Native title exists in the entire determination area Register Extract (pursuant to s. 193 of the Native Title Act 1993) Determination Date: 16/05/2013 Determining Body: Federal Court of Australia ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: Not Applicable REGISTERED NATIVE TITLE BODY CORPORATE: Western Desert Lands Aboriginal Corporation (Jamukurnu- Yapalikunu) RNTBC Trustee Body Corporate PO Box 331 WEST PERTH Western Australia 6872 Note: current contact details for the Registered Native Title Body Corporate are available from the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations www.oric.gov.au COMMON LAW HOLDER(S) OF NATIVE TITLE: SCHEDULE FOUR - NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS Part One 1. In respect of the whole of the Determination Area, except for the parts described in Part Two below, the persons referred to in paragraph 2(a) are those people known as the Martu People. The Martu People are those Aboriginal people who hold in common the body of traditional law and culture governing the Determination Area and who identify as Martu and who, in accordance with their traditional laws and customs, identify themselves as being members of one, some or all of the following language groups: National Native Title Tribunal Page 1 of 9 Extract from the National Native Title Register WCD2013/002 (a) Manyjilyjarra; (b) Kartujarra; (c) Kiyajarra; (d) Putijarra; (e) Nyiyaparli; (f) Warnman; (g) Ngulipartu; (h) Pitjikala; (i) Karajarra; (j) Jiwaliny; (k) Mangala; and (l) Nangajarra. -

''Horizontal'' and ''Vertical'

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication ”Horizontal” and ”vertical” skewing: similar objectives, two solutions? Laurent Dousset To cite this version: Laurent Dousset. ”Horizontal” and ”vertical” skewing: similar objectives, two solutions?. Thomas R. Trautmann and Peter M. Whiteley. Crow-Omaha: New Light on a Classic Problem of Kinship analysis, University of Arizona Press, pp.261-277, 2012, Amerind Studies in Anthropology. halshs- 00743744 HAL Id: halshs-00743744 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00743744 Submitted on 8 Jun 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License This is a preliminary and pre-print version of DOUSSET, Laurent 2012. ‘“Horizontal” and “vertical” skewing: similar objectives, two solutions?’. In Thomas R. Trautmann and Peter M. Whiteley (eds), Crow-Omaha: New Light on a Classic Problem of Kinship analysis. Tucson: Arizona University Press, p. 261-277. Laurent Dousset “Horizontal” and “vertical” skewing: similar objectives, two solutions? Introduction 1 In 1975, Robert Tonkinson presented a paper at a seminar that remained largely unknown and that Bob himself unfortunately has never published. -

Martu Paint Country

MARTU PAINT COUNTRY THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF COLOUR AND AESTHETICS IN WESTERN DESERT ROCK ART AND CONTEMPORARY ACRYLIC ART Samantha Higgs June 2016 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University Copyright by Samantha Higgs 2016 All Rights Reserved Martu Paint Country This PhD research was funded as part of an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Project, the Canning Stock Route (Rock art and Jukurrpa) Project, which involved the ARC, the Australian National University (ANU), the Western Australian (WA) Department of Indigenous Affairs (DIA), the Department of Environment and Climate Change WA (DEC), The Federal Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA, now the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Population and Communities) the Kimberley Land Council (KLC), Landgate WA, the Central Desert Native Title Service (CDNTS) and Jo McDonald Cultural Heritage Management Pty Ltd (JMcD CHM). Principal researchers on the project were Dr Jo McDonald and Dr Peter Veth. The rock art used in this study was recorded by a team of people as part of the Canning Stock Route project field trips in 2008, 2009 and 2010. The rock art recording team was led by Jo McDonald and her categories for recording were used. I certify that this thesis is my own original work. Samantha Higgs Image on title page from a painting by Mulyatingki Marney, Martumili Artists. Martu Paint Country Acknowledgements Thank you to the artists and staff at Martumili Artists for their amazing generosity and patience. -

WA Health Language Services Policy

WA Health Language Services Policy September 2011 Cultural Diversity Unit Public Health Division WA Health Language Services Policy Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Government policy obligations ................................................................................................... 2 2. Policy goals and aims .................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Scope......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Guiding principles ............................................................................................................................................. 6 5. Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 6. Provision of interpreting and translating services .................................................................... -

Making the Journey

Making the Journey Arts and disability in Australia Mary Hutchison © 2005 Arts Access Australia Designed by Boccalatte Printed in Australia by Lamb Printers Pty Ltd Arts Access Australia c/— Accessible Arts Pier 4, The Wharf, Hickson Rd Walsh Bay, NSW 2000, Australia National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Hutchison, Mary Making the journey: arts and disability in Australia ISBN 097513 230 X 1. People with disabilities and the arts — Australia. 2. People with disabilities and the performing arts — Australia. 3. People with disabilities — Education — Australia. I. Arts Access Australia. II. Title. 790.196 This book is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owner. Neither may information be stored electronically in any form whatsoever without such permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. Front cover photo: Ensemble members of the Back to Back Theatre production Mental: Rita Halabarec, Mark Deans, Darren Riches and Sonia Teuben. (Not pictured: Nicki Holland.) Photograph by Jeff Busby. Making the Journey Arts and disability in Australia Mary Hutchison In many areas of Indigenous Australia it is considered offensive to publish photographs or the names of Aboriginal people who have recently died. Readers are warned that this book may inadvertently contain such names or pictures. Foreword Department of Family and Community Services The Howard Government is pleased to Support is delivered by several Australian endorse activities celebrating the ability Government Departments, as well as state of people with disability and which and territory services receiving Howard remove barriers to their full participation Government funding to provide a range of in the community. -

Revealed Catalogue 2008

R e v e a l e d Cover image: Karnti Season (Bush Potato Season) Eva Nargoodah, Mangkaja Arts Photo: Tim Acker R e v e a l e d Emerging Artists from Western Australia’s Aboriginal Art Centres 25 October - 15 November, 2008 Revealed is presented in association with the Government of Western Australia’s Department of Culture and the Arts and the Department of Industry and Resources Message from the Government of Western Australia Hon. Troy Buswell MLA John Day MLA Treasurer; Minister for Commerce; Science and Innovation Minister of Culture and the Arts Aboriginal art provides Australia with an iconic and recognisable national and The Western Australian State Government is committed to the development of this international identity. Aboriginal art is one of the most important means for Aboriginal important arts sector. people, particularly those in remote areas, to participate in mainstream economic systems, which also provides contemporary relevance for maintaining the cultural Indigenous cultural expression is essential to the unique culture of Western Australia integrity that drives the industry. and celebrated world-wide. The Aboriginal Economic Development Division within the Department of Industry It is an industry which tends to focus on the successful works of elderly artists, often and Resources (DoIR) is the Western Australian Government’s key agency for distracting attention from the emerging artists in each region. support and advice to Aboriginal enterprise development. Revealed is an important partnership between the Department of Culture and the Arts In response to the identified need for a strategic approach to supporting esternW and the Aboriginal Economic Development Division of the Department of Industry and Australian’s most significant visual arts industry, DoIR developed the Arts Resources, and Central TAFE. -

Beyond Fictions of Closure in Australian Aboriginal Kinship

MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 1 MAY 2013 BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP WOODROW W. DENHAM, PH. D RETIRED INDEPENDENT SCHOLAR [email protected] COPYRIGHT 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY AUTHOR SUBMITTED: DECEMBER 15, 2012 ACCEPTED: JANUARY 31, 2013 MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ISSN 1544-5879 DENHAM: BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE WWW.MATHEMATICALANTHROPOLOGY.ORG MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 1 PAGE 1 OF 90 MAY 2013 BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP WOODROW W. DENHAM, PH. D. Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Dedication .................................................................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 3 1. The problem ........................................................................................................................ 4 2. Demographic history ......................................................................................................... 10 Societal boundaries, nations and drainage basins ................................................................. 10 Exogamy rates ...................................................................................................................... -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

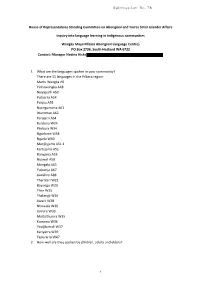

Submission No.78

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Inquiry into language learning in Indigenous communities Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre} PO Box 2736, South Hedland WA 6722 Contact: Manager Nadine Hicks 1. What are the languages spoken in your community? There are 31 languages in the Pilbara region: Martu Wangka A6 Yinhawangka A48 Nyiyaparli A50 Putijarra A54 Palyku A55 Nyangumarta A61 Warnman A62 Karajarri A64 Burduna W24 Pinikura W34 Ngarluma W38 Ngarla W40 Manjilyjarra A51.1 Kartujarra A51 Banyjima A53 Nyamal A58 Mangala A65 Yulparija A67 Juwaliny A88 Tharrkari W21 Bayungu W23 Thiin W25 Thalanyji W26 Jiwarli W28 Nhuwala W30 Jurruru W33 Martuthunira W35 Kurrama W36 Yindjibarndi W37 Kariyarra W39 Yapurarra W47 2. How well are they spoken by children, adults and elders? 1 This varies widely. While some languages such as Thiin are no longer spoken at all, others such as Martu Wangka are widely spoken by all age groups. Detailed information for each language is available on request. 3. Describe your group and project? Wangka Maya was begun by a group of Pilbara language speakers who were concerned at the loss of languages. It aims to record and foster the Aboriginal languages of the Pilbara region. The group began with no funding working as volunteers. Gradually they attracted project funding and eventually ongoing funding as a language centre. a) Why was it important to start up? Almost no work was being done to record or foster the use of local languages. b) How long have you been running? Since 1987 c) What age group(s) are you working with? All ages. -

Res Urces Catal

urces Res Catal gue 264 Hannan Street (08) 9021 3788 www.wangka.com.au New Language Desk Plaques $50.00 Language plaques are 30cm x 30cm in size and come in these languages; Kaalamaya, Ngaanyatjarra, Ngajumaya, Tjupan, Mirning, Cundeelee Wangka, Kuwarra, Ngalia and Wangkatja. 6 Piece Coaster Set $10.00 6 piece coaster set featuring Aboriginal bush foods such as the Honey Ant, Karlkurla and other yummy foods. Light weight material, perfect for posting. Childrens Books Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre has a variety of resources, please see price list at back of catalouge. If you are interested in any of the following resources please come and visit us at 264 Hannan Street. Books Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre has a variety of resources, please see price list at back of catalouge. If you are interested in any of the following resources please come and visit us at 264 Hannan Street. Books Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre has a variety of resources, please see price list at back of catalouge. If you are interested in any of the following resources please come and visit us at 264 Hannan Street. Learning resources Goldfields Aboriginal Language Centre has a variety of resources, please see price list at back of catalouge. If you are interested in any of the following resources please come and visit us at 264 Hannan Street. Learning resources Price List Titles A - D A Town is Born: Fitzroy Crossing $40 AIATSIS Map, small $30 Alphabet and syllables charts- each language $10 Art and Songs from the Spinifex People $20 Australian -

Materialities in Australian Aboriginal Kinship Laurent Dousset

From structure to substance and back: materialities in Australian Aboriginal kinship Laurent Dousset To cite this version: Laurent Dousset. From structure to substance and back: materialities in Australian Aboriginal kin- ship. Australian Aboriginal Anthropology Today: Critical Perspectives from Europe, Jan 2013, Paris, France. halshs-00781370 HAL Id: halshs-00781370 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00781370 Submitted on 7 Feb 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ANTHROPOLOGY « Australian Aboriginal Anthropology Today: Critical Perspectives from Europe » January 22-24th, 2013 Musée du Quai Branly From structure to substance and back : materialities in Australian Aboriginal kinship by Laurent Dousset (CREDO, EHESS) Aix Marseille Université, CNRS, EHESS, CREDO UMR 7308, 13003, Marseille, France *** In Race et Histoire, Lévi-Strauss wrote a few very interesting sentences, which I must quote here to some extend as a start: “For all that touches on the organization of the family and the harmonization of the relationship between family group and social group, the Australians, although backwards with regard to economy, occupy such an advanced position in comparison to the rest of humanity that it is, to understand the systems of rules that they have elaborated in a reflected and conscious manner, necessary to appeal to the most refined forms of modern mathematics….