Materialities in Australian Aboriginal Kinship Laurent Dousset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hdl 67064.Pdf

1 2 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CHRISTIES BEACH ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 PART 1: PRECEDENTS AND „BEST PRACTICE‟ DESIGN ................................................... 10 The Design of Early Learning, Child- care and Children and Family Centres for Aboriginal People ........................................................................................................ 10 Conceptions of Quality ............................................................................................... 10 Precedents: Pre-Schools, Kindergartens, Child and Family Centres ......................... 12 Kulai Aboriginal Preschool ............................................................................ 12 The Djidi Djidi Aboriginal School ................................................................... 13 Waimea Kohanga Reo Victory School .......................................................... 15 Mnjikaning First Nation Early Childhood Education Centre........................... 16 Native Child and Family Services of Toronto ............................................... -

''Horizontal'' and ''Vertical'

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication ”Horizontal” and ”vertical” skewing: similar objectives, two solutions? Laurent Dousset To cite this version: Laurent Dousset. ”Horizontal” and ”vertical” skewing: similar objectives, two solutions?. Thomas R. Trautmann and Peter M. Whiteley. Crow-Omaha: New Light on a Classic Problem of Kinship analysis, University of Arizona Press, pp.261-277, 2012, Amerind Studies in Anthropology. halshs- 00743744 HAL Id: halshs-00743744 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00743744 Submitted on 8 Jun 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License This is a preliminary and pre-print version of DOUSSET, Laurent 2012. ‘“Horizontal” and “vertical” skewing: similar objectives, two solutions?’. In Thomas R. Trautmann and Peter M. Whiteley (eds), Crow-Omaha: New Light on a Classic Problem of Kinship analysis. Tucson: Arizona University Press, p. 261-277. Laurent Dousset “Horizontal” and “vertical” skewing: similar objectives, two solutions? Introduction 1 In 1975, Robert Tonkinson presented a paper at a seminar that remained largely unknown and that Bob himself unfortunately has never published. -

WA Health Language Services Policy

WA Health Language Services Policy September 2011 Cultural Diversity Unit Public Health Division WA Health Language Services Policy Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Government policy obligations ................................................................................................... 2 2. Policy goals and aims .................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Scope......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Guiding principles ............................................................................................................................................. 6 5. Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 6. Provision of interpreting and translating services .................................................................... -

European Cultural Heritage Online

European Cultural Heritage Online ECHO PUBLIC Contract n°: HPSE / 2002 / 00137 Title: NECEP (Non European Components of European Patrimony) This document includes the following features: Annexes of : - the NECEP prototype specifications (report D2.1) - technical realization (report D2.2) Author(s) : Laurent Dousset Concerned WPs : WP2 Abstract: This document describes the data structure specifications, the technological prerequisites and the technological implementation of the NECEP protoype. Additionally, it includes instructions for content providers wishing to add or modify data in the prototype. Published in : (see http://www.ehess.fr/centres/logis/necep/) Keywords: metadata, sql, php, xml, prototype, ethnology, anthropology Date of issue of this report: 30.10.2003 Project financed within the Key Action Improving the Socio-economic Knowledge Base Content European Cultural Heritage Online ......................................................................................................... 1 Appendix 1: complete set of SQL table creation commands, including those used by the search engine .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Appendix 2: Examples of XML files, one for each type...................................................................... 13 Society definition XML file, in this case society_4.xml ....................................................13 Article definition XML file, in this case article_32.xml -

State of Indigenous Languages in Australia 2001 / by Patrick Mcconvell, Nicholas Thieberger

State of Indigenous languages in Australia - 2001 by Patrick McConvell Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Nicholas Thieberger The University of Melbourne November 2001 Australia: State of the Environment Second Technical Paper Series No. 2 (Natural and Cultural Heritage) Environment Australia, part of the Department of the Environment and Heritage © Commonwealth of Australia 2001 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source and no commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those listed above requires the written permission of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the State of the Environment Reporting Section, Environment Australia, GPO Box 787, Canberra ACT 2601. The Commonwealth accepts no responsibility for the opinions expressed in this document, or the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this document. The Commonwealth will not be liable for any loss or damage occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this document. Environment Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication McConvell, Patrick State of Indigenous Languages in Australia 2001 / by Patrick McConvell, Nicholas Thieberger. (Australia: State of the Environment Second Technical Paper Series (No.1 Natural and Cultural Heritage)) Bibliography ISBN 064 254 8714 1. Aboriginies, Australia-Languages. 2. Torres Strait Islanders-Languages. 3. Language obsolescence. I. Thieberger, Nicholas. II. Australia. Environment Australia. III. Series 499.15-dc21 For bibliographic purposes, this document may be cited as: McConvell, P. -

Beyond Fictions of Closure in Australian Aboriginal Kinship

MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 1 MAY 2013 BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP WOODROW W. DENHAM, PH. D RETIRED INDEPENDENT SCHOLAR [email protected] COPYRIGHT 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BY AUTHOR SUBMITTED: DECEMBER 15, 2012 ACCEPTED: JANUARY 31, 2013 MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ISSN 1544-5879 DENHAM: BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE WWW.MATHEMATICALANTHROPOLOGY.ORG MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 5 NO. 1 PAGE 1 OF 90 MAY 2013 BEYOND FICTIONS OF CLOSURE IN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL KINSHIP WOODROW W. DENHAM, PH. D. Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Dedication .................................................................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 3 1. The problem ........................................................................................................................ 4 2. Demographic history ......................................................................................................... 10 Societal boundaries, nations and drainage basins ................................................................. 10 Exogamy rates ...................................................................................................................... -

What's in a Name? a Typological and Phylogenetic

What’s in a Name? A Typological and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Names of Pama-Nyungan Languages Katherine Rosenberg Advisor: Claire Bowern Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract The naming strategies used by Pama-Nyungan languages to refer to themselves show remarkably similar properties across the family. Names with similar mean- ings and constructions pop up across the family, even in languages that are not particularly closely related, such as Pitta Pitta and Mathi Mathi, which both feature reduplication, or Guwa and Kalaw Kawaw Ya which are both based on their respective words for ‘west.’ This variation within a closed set and similar- ity among related languages suggests the development of language names might be phylogenetic, as other aspects of historical linguistics have been shown to be; if this were the case, it would be possible to reconstruct the naming strategies used by the various ancestors of the Pama-Nyungan languages that are currently known. This is somewhat surprising, as names wouldn’t necessarily operate or develop in the same way as other aspects of language; this thesis seeks to de- termine whether it is indeed possible to analyze the names of Pama-Nyungan languages phylogenetically. In order to attempt such an analysis, however, it is necessary to have a principled classification system capable of capturing both the similarities and differences among various names. While people have noted some similarities and tendencies in Pama-Nyungan names before (McConvell 2006; Sutton 1979), no one has addressed this comprehensively. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

Good, Strong, Powerful Education

ResearchGOODSTRONG NotesPOWERFUL Adrian Robertson Jangala, Yalpirakinu 2010, Acrylic paint on linen Good Strong Powerful is an exhibition of paintings that celebrate the individuality, diversity and vision of ten Indigenous artists from three innovative Northern Territory art studios. Good Strong Powerful offers students a unique insight into the lives of these contemporary artists and the world in which they live. Good Strong Powerful challenges Western notions of disability and acknowledges the major contribution these artists make to the artistic and cultural life of their people and the broader community. The Education Kit provides an introduction to the exhibition from an educational perspective. Research Notes GOODSTRONGPOWERFUL Index Acknowledgments 3 Where the Artists Live - Map 4 Community Support 5 Ability and Disability 6 Catalogue Essay - Dr Sylvia Kleinert 7 Artists - Information 9 Adrian Robertson Tjangala 9 Alfonso Puautjimi 10 Billy Benn Perrurle 11 Billy Kenda Tjampitjinpa 12 Dion Beasley 13 Estelle Munkanome 14 Kukula McDonald 15 Lance James 16 Lorna Kantilla 17 Peggy Jones Napangardi 18 Internet Links 19 Curriculum Links 19 Indigenous Knowledge & Protocols 20 www.artbacknt.com.au 2 Research Notes GOODSTRONGPOWERFUL Artists Acknowledgements From Tiwi Islands These materials were developed by Artback NT for use in schools and at exhibition venues. • Lorna Kantilla The activities may be reproduced for teaching • Alfonso Puautjimi purposes. Permission to reproduce any material • Estelle Munkanome for other purposes must be obtained from Artback NT. From Alice Springs Exhibition Curator • Billy Benn Perrurle • Kukula McDonald Penny Campton • Billy Kenda Program Officer, Arts Access Darwin. • Adrian Robertson • Lance James Education Kit Angus Cameron From Tennant Creek Nomad Art Productions, Darwin. -

A Linguistic Bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands

OZBIB: a linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands Dedicated to speakers of the languages of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands and al/ who work to preserve these languages Carrington, L. and Triffitt, G. OZBIB: A linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. D-92, x + 292 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D92.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian NatIonal University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. -

16629 Dixon Et Al 2006 Back

Index This is an index of some of the more important terms from Chapter 6,of the names of Australian Aboriginal languages (or dialects), and of loan words from Australian languages (including some words of uncertain origin and some, like picaninny, wrongly thought of as Aboriginal in origin). Variant spellings are indexed either in their alphabetical place or in parentheses after the most usual spelling. References given in bold rype are to the main discussion of a loan word or language. Aboriginal art, 239-40 Baagandji, xiii, 27-8,58,100, 148, Aboriginal Embassy,244 192,195 Aboriginal Flag,244 baal (bael,bail), 22, 205-6,213, 218 Aboriginal time,236 Bajala,43 Aboriginal way,244 balanda,222 Aboriginaliry,244 bale,see baal acrylic art,240 balga,125 adjigo (adjiko), 33, 118,214 ball art,108 Adnyamathanha, xiii, 14,39-40,56, bama,162,163,214 103,174 bandicoot, 50-1 alcheringa (alchuringa),47, 149 Bandjalang, xiii, 20,25-6, 103,119, alunqua,107,212-13 127, 129,132, 137 Alyawarra,46-7 bandy-bandy, 99 amar,see gnamma hole bangala�27,107, 126,213 amulla,107 bangalow,27,121,213 anangu,162, 163 banji, 164 ancestral beings (and spirits),241 Bardi,xiii, 151,195 Anmatjirra, 46 bardi (grub) (barde, bardee,bardie), apology,246 16,30,101-2 Arabana,xiii, 41,187 bardy,see bardi Aranda,xiii, 46-7, 107, 117, 120, bark canoe,239 149-50,155,169,172-3 bark hut,239 ardo,see nardoo bark painting,240 Arrernte,see Aranda barramundi (barra, barramunda), 90, art,239-40 215 Arunta,see Aranda beal,see belah assimilation,243 bel,see baal Awabakal, xiii, 20, 161, 163, 167,196 belah (belar),126, 132,213 .,. -

Captured-State-Report.Pdf

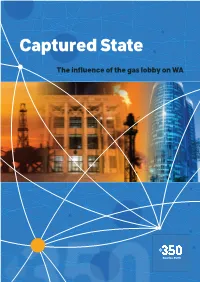

KEY Current or former Labor politicians Link individuals to entities they Lobby groups or membership groups with WA’s revolving doors currently, or have previously, significant lobbying resources Current or former Liberal politicians worked for. Government agencies or departments Current or former Nationals politicians Fossil fuel companies Non Fossil fuel companies with strong ties to the oil & gas or resources sector. A map of the connections between politics, government Individuals who currently, or have previously, worked for entities they agencies and the gas industry, withafocus on WA are connected to on the map. IndependentParliamentary KEY Current or former Labor politicians Link individuals to entities they Lobby groups or membership groups with WA’s revolving doors currently, or have previously, significant lobbying resources Current or former Liberal politicians worked for. Government agencies or departments Current or former Nationals politicians Fossil fuel companies Non Fossil fuel companies with strong ties to the oil & gas or resources sector. A map of the connections between politics, government Individuals who currently, or have previously, worked for entities they agencies and the gas industry, withafocus on WA are connected to on the map. CapturedIndependentParliamentary State The influence of the gas lobby on WA KEY Current or former Labor politicians Link individuals to entities they Lobby groups or membership groups with WA’s revolving doors currently, or have previously, significant lobbying resources Current or former Liberal politicians worked for. Government agencies or departments Current or former Nationals politicians Fossil fuel companies Non Fossil fuel companies with strong ties to the oil & gas or resources sector. A map of the connections between politics, government Individuals who currently, or have previously, worked for entities they agencies and the gas industry, withafocus on WA are connected to on the map.