Maritime Culture in an Inland Lake?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

My Aim in Setting up the Boat Building Academy Was to Provide Training for Men and Women of All Ages

My aim in setting up the Boat Building Academy was to provide training for men and women of all ages that would carry forward the best traditions of British boat building and enable each of them to develop his or her potential using the best modern techniques in boat construction. I am particularly proud of the excellent standard that our students achieve and of the success that so many have made in their careers in the marine industry’. Commander Tim Gedge. Director, Boat Building Academy 1 Contents Boat Building Academy Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 Courses ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Boat Building, Maintenance and Support 40 week City & Guilds Level 3 (the ‘long’ course) ................................................................ 5 Build your own boat ............................................................................................................. 8 Boat launches/Outings ........................................................................................................ 9 Furniture Making ................................................................................................................. 10 Advanced Furniture Making ....................................................................................... 12 Short courses ........................................................................................................................... -

Boatwright's Lapstrake Toolbox

Folk School Fairbanks 1 Boatwright’s Lapstrake Toolbox An “All Things Boats” Introductory Project By Bruce W. Campbell January 20, 2015 Table of Contents Why Build a Lapstrake Toolbox? 2 Tools 4 Class Material List 5 Lapstrake Toolbox Construction Steps 6 Illustrated Construction Steps 8 Side and End Views 20 Lapstrake Toolbox vs. Lapstrake Boats 24 What is a Lap? 24 A Few Words 28 References & Recommended Reading 29 Epoxy Safety 30 Why Build a Lapstrake Toolbox? This project introduces wooden boat building techniques and methods but without the time commitment and cost of building a full size boat. Building this simple and unique toolbox is easier than building a small scale mod- el of a boat because it is larger in scale than a model, has Folk School Fairbanks 3 fewer parts than a model, and above all you don't have to decide on a boat design. The glued lap construction method is arguably the fast- est, strongest method for building a light, stiff, and round displacement hull. We will use modern epoxy and lightweight marine plywood. Marine plywood is stronger and more stable than straight grained lumber from old growth forests of yore. The epoxy joint between the planks is stronger and stiffer than clench nailing or rivet- ing. Glued lapstrake construction is free from internal ribs and frames, yet retaining the elegance of boats built in the 1890's and early 1900's. This introduction to glued lap construction is intended to allow you to create a unique toolbox you can use to proudly carry your tools to the next boat building class in your future! Tools we will use: Low angle block plane with lap bevel guide Back saw or fine toothed pull saw 1/2 inch chisel Random Orbital Sander (Makita 2 amp or better) Ziploc bag to col- lect sanding dust for epoxy putty 8 oz. -

Newsletter May 2016 Registered Charity No.1105449 Unit 20, Estuary Road, Queensway Meadows Industrial Estate, Newport, NP19 4SP

Newsletter May 2016 Registered Charity No.1105449 Unit 20, Estuary Road, Queensway Meadows Industrial Estate, Newport, NP19 4SP www.newportship.org Chairman’s Introduction Welcome to your May edition of the FoNS Newsletter. We are pleased to be able to bring more articles from varied contributors from within the membership, looking at subjects associated with the heart of our society. I find these fascinating and would encourage others to come forward and develop their ideas for the wider audience. Phil Cox, Chairman Desperately Seeking Secretary Many of you will know Sian King, our current Secretary who has brought order to our midst and doubtless hassled and harangued members for their renewal subscriptions as well as providing an excellent administrative service to the committee. Sian is standing down and we are desperately seeking somebody to fill her shoes. We intend to split the role, so that we are looking for a ‘Secretary’ to run the administration of the charity and to act as minute-taker. In addition, we are seeking a Membership Secretary to run the database, chase subscriptions, and distribute newsletters and other official papers as agreed by the committee. If you have the time and the inclination to undertake either or both of these roles, please get in touch with me at [email protected]. I have to say that Sian will be sorely missed at committee and I anticipate that she will continue to advertise the Newport Medieval Ship project through her other works. The Annual FoNS Trip This year we are visiting Pembroke Castle, the Sunderland Flying Boat Museum & Milford Haven Maritime Museum on Thursday 16th June. -

Shipbuilding and the English International Timber Trade, 1300-1700: a Framework for Study Using Niche Construction Theory

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 2009 Shipbuilding and the English International Timber Trade, 1300-1700: a framework for study using Niche Construction Theory Jillian R. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Smith, Jillian R., "Shipbuilding and the English International Timber Trade, 1300-1700: a framework for study using Niche Construction Theory" (2009). Nebraska Anthropologist. 49. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/49 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Shipbuilding and the English International Timber Trade, 1300-1700: a framework for study using Niche Construction Theory Jillian R. Smith Abstract: Much scholarship has been undertaken with regards to the evolution of the European shipbuilding traditions and their physical changes, but few explanations for the changes are given. This paper seeks to identify the correlations between the expansion of the English timber trade in the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries and the changes in shipbuilding at the time, thereby creating a framework for future study of this correlation and its possible relatedness using Niche Construction Theory as a framework. Directions the research can take and the data needed are the focus of this work. English trade has long been dependent upon the sea as the main thoroughfare for goods traveling to and from the island. Boats and ships of various sizes, shapes, and varieties have in tum, until the last century with airplanes and the Channel Tunnel, been the primary means of leaving England for any purpose. -

UPPSALA UNIVERSITET Västergarn Boat Rivets in Context

UPPSALA UNIVERSITET Institutionen fö r arkeologi och antik historia Västergarn Boat Rivets in Context Case study : The Missing Boatyard Richard Koehler MA thesis 30 credits in Archaeology Spring term 2020 Supervisor: Christoph Kilger Campus Gotland 1 Abstract Koehler, Richard (2020). Västergarn Boat Rivets in Context, Case study: The Missing Boatyard Koehler, Richard (2020). Skeppsnitar och båtvarv i Västergarn. En kontextuell fallstudie Gotland has a rich material cultural heritage from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages thanks to the island's strategic location in the middle of the Baltic Sea; especially true for the Viking Age when Gotlanders had extensive trade contacts with the east dating from the mid 12th century and Gotland’s economy was dominated by such contacts. This essay deals with Gotland's maritime infrastructure and its development between about 1100 and 1400 based on a case study of boat rivets from the medieval settlement of Västergarn. The study focus is on Västergarn’s emergence as a maritime community on Gotland's west coast, and if Västergarn had the opportunity to decide its own economy, i.e., to control its’ external contacts and internal trade with the rest of Gotland? What role did maritime traffic play in Västergarn economy? Is it possible to draw conclusions about site maritime organization and infrastructure based on the extensive rivet material? What supply chains with the surrounding area may have existed that made such activity possible? What professional skills and knowledge were in place? In the analytical part of the dissertation a classification system for Västergarn's rivet material is established and discussed in comparison with other literature on boat building technology from the rest of Scandinavia, in particular the Baltic Sea area. -

Wooden Boatbuilding Or How to Build Strong, Lightweight, Streamlined Shapes

Wooden Boatbuilding Or How to build strong, lightweight, streamlined shapes. Joint Presentation • Introduction to Wooden Boat Building (Jerry) • Wooden Boat Building Methods (Tim) • Building a Tortured Plywood Boat (Jerry) • Plywood Lapstrake Boat Joinery (Jerry) • Building a Stitch and Glue Boat (Nelson) Wooden vs Fiberglass Boats • Fiberglass Suitable for Mass Production and Cheaper • Often Two Molds: Hull and Deck/Cabin • Attach and/or Bond the Deck/Cabin to the Hull • Wooden Hull Shapes Not Constrained by a Mold • Wooden Hulls Can Have Better Strength to Weight Ratio Graham Byrnes’ Outer Banks 20 Example of Sheet Plywood Bottom and Ashcroft Sides Howard Rice’s Southern Cross Explored Tierra del Fuego in a Modified 12 foot SCAMP • Survived Rare 70 knot Cyclonic Winds • Kelp Blocked Two Safe Anchorages • Abandoned Boat and Swam Ashore • Rescued by Chilean Patrol Boat • Southern Cross Rescued 3/5/2017 http://www.mysailing.com.au/cruising/howard- rice-the-end-of-the-south-american-adventure- comes-in-dramatic-fashion Form Follows Function • How a Boat is Used influences Hull Shape • Hull Shape Influences Building Methods • Monohulls • Displacement • Planing • Semi-Displacement • Multihulls • Catamaran • Trimaran Displacement Hull • Held Up By Buoyancy, i.e, Static Force • Not Designed to Exceed Displacement Speed • Characterized by a Curved Underwater Surface • Minimize Bow and Stern Waves for Efficiency Displacement Hull Speed hull speed (knots) = 1.34 x square root of length at waterline (ft) Planing Hull • Add Hydrodynamic Force • -

Maritime and Naval Scheduling Selection Guide Summary

Maritime and Naval Scheduling Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s scheduling selection guides help to define which archaeological sites are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. For archaeological sites and monuments, they are divided into categories ranging from Agriculture to Utilities and complement the listing selection guides for buildings. Scheduling is applied only to sites of national importance, and even then only if it is the best means of protection. Only deliberately created structures, features and remains can be scheduled. The scheduling selection guides are supplemented by the Introductions to Heritage Assets which provide more detailed considerations of specific archaeological sites and monuments. This selection guide offers an overview of the sorts of archaeological monument or site with maritime or naval associations which are likely to be deemed to have national importance, and for which of those scheduling may be appropriate. It aims to do two things: to set these within their historical context, and to give an introduction to the designation approaches employed. This document has been prepared by Listing Group. It is one is of a series of 18 documents. This edition published by Historic England July 2018. All images © Historic England unless otherwise stated. Please refer to this document as: Historic England 2018 Maritime and Naval: Scheduling Selection Guide. Swindon. Historic England. HistoricEngland.org.uk/listing/selection-criteria/scheduling-selection/ Front cover The pharos (lighthouse) at Dover, Kent, England’s tallest Roman structure. It later served as the bell tower for the Saxon church of St Mary in Castro. -

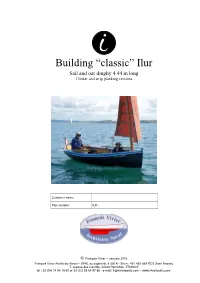

Building “Classic” Ilur Sail and Oar Dinghy 4.44 M Long Clinker and Strip Planking Versions

Building “classic” Ilur Sail and oar dinghy 4.44 m long Clinker and strip planking versions Customer name: Plan number: ILR - © François Vivier – January 2016 François Vivier Architecte Naval – SARL au capital de 8 000 € - Siren : 451 456 669 RCS Saint Nazaire 7, avenue des Courtils, 44380 Pornichet - FRANCE tel : 33 (0)6 74 54 18 60 or 33 (0)2 28 54 97 86 - e-mail: [email protected] – www.vivierboats.com January 2016 Building classic Ilur Page 2/22 1. List of documents Important: since March 2011, there is 2 different plan packages for Ilur: • The “classic” Ilur which allows to build Ilur either with a clinker or strip planked hull, with or without the help of full size polyester full size patterns. • The new “clinker–kit” Ilur which, as the title says, is clinker built from a plywood cut kit marketed by several boat-builders partners. This new version has plywood transverse bulkheads instead of traditional steam bent or lamin- ated frames. The interest of this version is to be easier to build and to allow a 25% saving in working time. 1.1. The present manual 1.2. Appendices Numb Rev Title Date Pages 1 8 Timber list 27 May 2014 4 2 6 Plywood panels list 11 December 2012 8 3 3 Plywood panels list (strip planking version) 30 August 2007 3 4 4 Fittings list 27 May 2014 4 1.3. “Wooden boatbuilding” sheets (mainly in French) These documents are extracts from my book on wooden boat construction, “Construction bois les techniques mod- ernes” (in French). -

Appendix of Chapter 4

Study on the Development of Domestic Sea Transportation and Maritime Industry in the Republic of Indonesia (STRAMINDO) - Final Report - APPENDIX OF CHAPTER 4 4.1 Industrial Carrier Case Study: ITP Tunggal Perkasa (1) Profile Year of Establishment: 1973 Status: PMA (Penanaman Modal Asing) Ownership Type: Foreign Investment (German) Share: Heidelberg (German company) (75-80%) Government (under 10%) Private (10%) Public (under 10%) Number of Employees: 8,000 persons Capital Investment: 1,000,000 $ US ITP is the biggest cement company in Indonesia. Capacity of ITP Plant Figure 4.1 Cement Processing ITP Production gypsum Raw material burning clinker granding Packaging (bag) Table 4.1 Capacity of Cement Plant in Citeurep (Jawa Barat) Plant Year Capacity / year (ton) 1 1975 500,000 2 1976 500,000 3 1979 1,000,000 4 1981 1,000,000 5 1981 200,000 6 1983 1,500,000 7 1985 1,500,000 8 1985 2,000,000 11 1999 2,450,000 Total 10,650,000 Table 4.2 Capacity of Cement Plant in Palimanan/Cirebon (Jawa Barat) Plant Year Capacity / year (ton) 9 1985 1,300,000 10 1997 1,300,000 Total 2,600,000 Appendix-17 Study on the Development of Domestic Sea Transportation and Maritime Industry in the Republic of Indonesia (STRAMINDO) - Final Report - Table 4.3 Capacity of Cement Plant in Tarjun (Kalimantan Selatan) Plant Year Capacity / year (ton) 12 1998 2,450,000 ITP has four terminals: Jakarta, Bandung, Semarang, and Surabaya. It planned to expand production 20 years later after operation, however, future investment plans were derailed due to Indonesia’s economic crisis. -

Wooden Boat Restoration & Repair

002-970 Wooden Boat Restoration & Repair A guide to restore the structure, improve the appearance, reduce the maintenance and prolong the life of wooden boats with WEST SYSTEM® Epoxy. 002-970 Wooden Boat Restoration & Repair 8th Edition—January 2018 The techniques described in this manual are based on the handling techniques and physical properties of WEST SYSTEM Epoxy products. Because physical properties of resins systems and epoxy brands vary, using the techniques in this publication with coatings or adhesives other than WEST SYSTEM is not recommended. This manual is updated as products and techniques change. If the last copyright date below is more than several years old, contact your WEST SYSTEM dealer or Gougeon Brothers, Inc. for a current version. The information presented herein is believed to be reliable as of publication date, but we cannot guarantee its accuracy in light of possible new discoveries. Because Gougeon Brothers, Inc. cannot control the use of WEST SYSTEM products in customer possession, we do not make any warranty of merchantability or any warranty of fitness for a particular use or purpose. In no event shall Gougeon Brothers, Inc. be liable for incidental or consequential damages. WEST SYSTEM, 105 Epoxy Resin, 205 Fast Hardener, 206 Slow Hardener, 410 Microlight, G/flex and Six10 are all registered trademarks of Gougeon Brothers, Inc. 207 Special Clear Hardener, 209 Extra Slow Hardener are trademarks of Gougeon Brothers, Inc. Copyright © September 1990, December 1992, June 1997, May 1999, September 2000, April 2003, December 2008, January 2018 by Gougeon Brothers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. -

Building-A-Boat-From-Old-Plans.Pdf

BUILDING A BOAT FROM OLD PLANS The information below is supplied by MGYD (Mertens-Goossens Yacht Design Inc.), a company with 25 years’ experience in boat design for amateurs. WHERE DO THE FREE BOAT PLANS COME FROM? There are many old boat plans in the public domain available on the Internet. For many of those plans, the copyright has expired, and they are available for free if you know where to look. Some old plans have been maintained, the copyrights are still in effect, and those plans are legitimately sold, the Atkins designs are a good example. Free copies of public domain old plans can be downloaded from web sites like Svenson or better, BoatPlans-OnLine.com. Some copies of the same old plans are sold at various web sites and on eBay, sometimes at an exorbitant price. They talk about a “master boat builder” and his secrets but those are the same plans as the ones above, assembled on a CD. Despite their advertisement, you will not receive nice boxed software or a booklet but just a plain CD in an envelope, with the same copies of plans as the ones listed for free at BoatPlans- Online.com. There are other legitimate sources of free or almost free plans. Many designers offer one or two free plans as a sample of their work. Then there is DNGoodchild, a company that reprints some of those old plans in high quality format for a small fee. There may be others but, in most cases, your free boat plans will come from one of the web sites above and be copies of old plans published in magazines.