Introductions to Heritage Assets: Ships and Boats: Prehistory to 1840

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser

ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser: Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, May 2019 June 2019: Admiral Sir Antony D. Radakin: First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, June 2019 (11/1965; 55) VICE-ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 February 2016: Vice-Admiral Sir Benjamin J. Key: Chief of Joint Operations, April 2019 (11/1965; 55) July 2018: Vice-Admiral Paul M. Bennett: to retire (8/1964; 57) March 2019: Vice-Admiral Jeremy P. Kyd: Fleet Commander, March 2019 (1967; 53) April 2019: Vice-Admiral Nicholas W. Hine: Second Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, April 2019 (2/1966; 55) Vice-Admiral Christopher R.S. Gardner: Chief of Materiel (Ships), April 2019 (1962; 58) May 2019: Vice-Admiral Keith E. Blount: Commander, Maritime Command, N.A.T.O., May 2019 (6/1966; 55) September 2020: Vice-Admiral Richard C. Thompson: Director-General, Air, Defence Equipment and Support, September 2020 July 2021: Vice-Admiral Guy A. Robinson: Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Command, Transformation, July 2021 REAR ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 July 2016: (Eng.)Rear-Admiral Timothy C. Hodgson: Director, Nuclear Technology, July 2021 (55) October 2017: Rear-Admiral Paul V. Halton: Director, Submarine Readiness, Submarine Delivery Agency, January 2020 (53) April 2018: Rear-Admiral James D. Morley: Deputy Commander, Naval Striking and Support Forces, NATO, April 2021 (1969; 51) July 2018: (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Keith A. Beckett: Director, Submarines Support and Chief, Strategic Systems Executive, Submarine Delivery Agency, 2018 (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Malcolm J. Toy: Director of Operations and Assurance and Chief Operating Officer, Defence Safety Authority, and Director (Technical), Military Aviation Authority, July 2018 (12/1964; 56) November 2018: (Logs.) Rear-Admiral Andrew M. -

The Age of Exploration

ABSS8_ch05.qxd 2/9/07 10:54 AM Page 104 The Age of 5 Exploration FIGURE 5-1 1 This painting of Christopher Columbus arriving in the Americas was done by Louis Prang and Company in 1893. What do you think Columbus might be doing in this painting? 104 Unit 1 Renaissance Europe ABSS8_ch05.qxd 2/9/07 10:54 AM Page 105 WORLDVIEW INQUIRY Geography What factors might motivate a society to venture into unknown regions Knowledge Time beyond its borders? Worldview Economy Beliefs 1492. On a beach on an island in the Caribbean Sea, two Values Society Taino girls were walking in the cool shade of the palm trees eating roasted sweet potatoes. uddenly one of the girls pointed out toward the In This Chapter ocean. The girls could hardly believe their eyes. S Imagine setting out across an Three large strange boats with huge sails were ocean that may or may not con- headed toward the shore. They could hear the tain sea monsters without a map shouts of the people on the boats in the distance. to guide you. Imagine sailing on The girls ran back toward their village to tell the ocean for 96 days with no everyone what they had seen. By the time they idea when you might see land returned to the beach with a crowd of curious again. Imagine being in charge of villagers, the people from the boats had already a group of people who you know landed. They had white skin, furry faces, and were are planning to murder you. -

Scenario Book 1

Here I Stand SCENARIO BOOK 1 SCENARIO BOOK T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S ABOUT THIS BOOK ......................................................... 2 Controlling 2 Powers ........................................................... 6 GETTING STARTED ......................................................... 2 Domination Victory ............................................................. 6 SCENARIOS ....................................................................... 2 PLAY-BY-EMAIL TIPS ...................................................... 6 Setup Guidelines .................................................................. 2 Interruptions to Play ............................................................ 6 1517 Scenario ...................................................................... 3 Response Card Play ............................................................. 7 1532 Scenario ...................................................................... 4 DESIGNER’S NOTES ........................................................ 7 Tournament Scenario ........................................................... 5 EXTENDED EXAMPLE OF PLAY................................... 8 SETTING YOUR OWN TIME LIMIT ............................... 6 THE GAME AS HISTORY................................................. 11 GAMES WITH 3 TO 5 PLAYERS ..................................... 6 CHARACTERS OF THE REFORMATION ...................... 15 Configurations ..................................................................... 6 EVENTS OF THE REFORMATION -

London Southend Airport Consultation Feedback Report

London Southend Airport Consultation Feedback Report Introduction of New Approach Procedures Issue 1.1 Prepared by: NATS Unmarked London Southend Airport Consultation Feedback Report 2 Table of contents 1. Introduction 5 1.1. Project Overview 5 1.2. Consultation Overview 7 2. Confidentiality 8 3. Stakeholder Engagement 9 3.1. Introduction 9 3.2. National Air Traffic Management Advisory Committee 10 3.3. London Southend Airport Consultative Committee 11 3.4. Local Authorities 13 3.5. National Bodies 16 3.6. MPs 17 3.7. Airspace Users 18 3.8. Others 20 3.9. Members of the Public 20 4. Summary of Consultation Feedback 22 4.1. Stakeholder Invitees 22 4.2. Stakeholder Responses 23 4.3. Responses and Key Themes 24 5. Stakeholder Responses 26 5.1. Key Themes Raised by Stakeholders 26 5.2. Direct Questions Raised & Answers 30 5.3. Concerns Raised & Answers 32 6. Intention to Proceed with the Airspace Change Proposal 35 7. Post-Consultation Steps 37 7.1. Feedback to Stakeholders 37 7.2. Airspace Change Proposal 37 7.3. Post-Implementation Review 37 8. Further Correspondence & Feedback 38 Introduction of New Approach Procedures Page 2 of 40 London Southend Airport Consultation Feedback Report 3 Appendix A 39 Appendix B 40 List of Figures Figure 1 - Image illustrating London Southend CAS (incl. Danger Areas) ............................................ 5 Figure 2 - Image illustrating proposed RNAV routes & CAS .................................................................. 6 Figure 3 - Image illustrating missed approach and Runway 05 transition routes & CAS ................... 7 Figure 4 - Chart showing NATMAC responses...................................................................................... 11 Figure 5 - Chart showing LSACC responses .......................................................................................... 13 Figure 6 - Chart showing Kent Councils responses ............................................................................. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

1502-1629 THOUGH It Did Not Take Place Until Fifteen Years Later, the Discovery of St

CHAPTER I 1502-1629 THOUGH it did not take place until fifteen years later, the discovery of St. Helena became inevitable AL when the Portuguese navigator, Bartholomew de Diaz, rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1487. For many years the Portuguese, the greatest race of sailors who ever ventured into uncharted seas, excluded from the Mediterranean, had gradually explored farther and farther along the mysterious unmapped western coast of Africa. Ten years after the epoch-making discovery of Diaz and after Columbus and Cabot had opened up the Atlantic to the races of the West and North of Europe, the King of Portugal, Emmanuel the Fortunate, sent out a fleet under the command of Vasco da Gama with orders to sail beyond the Cape of Good Hope in search of a direct sea route to India and thus tap the wealth of the East. Hitherto for centuries all trade between Europe and the East had been carried overland across Arabia, and by ship along the Mediterranean, and had been in the hands of the Italian cities of Venice and Genoa. Da Gama achieved his ambition, and arrived at Calicut, on the west coast of the Indian Peninsula, and from that day the Mediterranean, which for centuries had been the centre of civilization, began to decline. The Portuguese lost no time in building forts and setting up trading posts along the west coast of India, but their principal one was at Calicut. I 5 021 ST. HELENA ST. HELENA [1502 It is not to be wondered at that the "Moors" or Arabs who by some strange fluke of fortune, is still existing and to be for centuries had held the monopoly of the trade between found in considerable numbers. -

Master Narrative Ours Is the Epic Story of the Royal Navy, Its Impact on Britain and the World from Its Origins in 625 A.D

NMRN Master Narrative Ours is the epic story of the Royal Navy, its impact on Britain and the world from its origins in 625 A.D. to the present day. We will tell this emotionally-coloured and nuanced story, one of triumph and achievement as well as failure and muddle, through four key themes:- People. We tell the story of the Royal Navy’s people. We examine the qualities that distinguish people serving at sea: courage, loyalty and sacrifice but also incidents of ignorance, cruelty and cowardice. We trace the changes from the amateur ‘soldiers at sea’, through the professionalization of officers and then ships’ companies, onto the ‘citizen sailors’ who fought the World Wars and finally to today’s small, elite force of men and women. We highlight the change as people are rewarded in war with personal profit and prize money but then dispensed with in peace, to the different kind of recognition given to salaried public servants. Increasingly the people’s story becomes one of highly trained specialists, often serving in branches with strong corporate identities: the Royal Marines, the Submarine Service and the Fleet Air Arm. We will examine these identities and the Royal Navy’s unique camaraderie, characterised by simultaneous loyalties to ship, trade, branch, service and comrades. Purpose. We tell the story of the Royal Navy’s roles in the past, and explain its purpose today. Using examples of what the service did and continues to do, we show how for centuries it was the pre-eminent agent of first the British Crown and then of state policy throughout the world. -

Enjoying Your Stay at the Hollies

Extraordinary holidays, celebrations &adventures Enjoying your stay at The Hollies Everything you need to get the most out ofyourstay kate & tom’s | 7 Imperial Square | Cheltenham | Gloucestershire | GL50 1QB | Telephone: 01242 235151 | Email: [email protected] Contents Arrival . 3 Where we are . 3 Check in and check out . 3 Getting to us . .4 Cooking & dining. .5 Chef services . .5 Great places to eat & drink . 6 Shopping for food . 9 Things to do . 12 Things to do with the children . .15 Useful information . 16 Guest reviews . 18 Page 2 kate & tom’s kateandtoms.com Telephone: 01242 235151 | Email: [email protected] Arrival Where we are Property name : Woollams Address: Botley Road Curdridge Southampton Hampshire SO32 2DQ Check in and check out Check in time: 2pm Check out time on Sundays: 4pm Check out time on other days: 12pm Page 3 kate & tom’s kateandtoms.com Telephone: 01242 235151 | Email: [email protected] Getting to us The best postcode to use for satnavs is: SO32 2DQ Stations: Botley 3 min (0.8 mi) via Botley Rd/B3035 Airports: Southampton 16 min (8.5 mi) via M27 Taxis: Hedge End: 01489 696969 The Bitterne Cab Company: 023 8044 8888 Directions From London • Take the M3 motorway, coming off at junction 11 at Winchester turning left on to the B3335 and • following the signs for Twyford and Marwell Zoo. • Go through Twyford and turn left on to the B2177 at Fisher’s Pond. Stay on this road and follow signs for Bishop’s Waltham. • Driving through Bishop’s Waltham, you’ll come to the Crown Pub on your left and you need to take the third exit at the roundabout here following signs for Botley. -

CLIPPER 021799 Asset Fact Sheets MARKETING

CLIPPER SEAL TS (BP) CA TEESSIDE CUTTER SOLE PIT CARRACK BARQUE GALLEON SHAMROCK CARAVEL EASINGTON CLIPPER BRIGANTINE CLIPPER SKIFF STANLOW INDE AMELAND INDE FIELD CORVETTE SEAN GRIJPSKERK SEAN FIELD LEMAN BACTON BBL DEN HELDER GREAT YARMOUTH BALGZAND INTERCONNECTOR EMMEN THE HAGUE SCHIEDAM LONDON CLIPPER ZEEBRUGGE CLIPPER Clipper is in the Southern part of the UK sector of the North Sea in the Sole Pit field. Located 113km (70 miles) north north east of Lowestoft, 73km (46 miles) from Bacton and 66km (41 miles) from the nearest point of the Norfolk coast. It is a Normally Attended Installation (NAI) comprising five fixed bridge linked platforms Clipper PW Wellhead Platform Clipper PT Production Platform - which is manned Clipper PC Compression Platform Clipper PM Metering / Compression Platform Clipper PR Riser Platform The Clipper installation produces and processes natural gas from its own wells and imports and processes gas from Barque PB & PL, Galleon PN & PG, Skiff PS, Cutter QC and Carrack QA. KEY FACTS Block 48/19a Sector Southern North Sea Approx distance to land 109km (68 miles) North of Lowestoft Water Depth 112ft (34m) Hydrocarbons Produced Gas Export Method Gas piped to Bacton Gas Terminal Operated / Non-Operated Operated Graphics, Media & Publication Services (Aberdeen) ITV/UZDC : Ref. 021799 January 2016 CLIPPER INFRASTRUCTURE INFORMATION Entry Specification: GSV 37-44.5MJ/sm3, Oxygen <0.2%, CO2 Max 2 mol%, H2S <3.3ppm, Total Sulphur <15ppm, WI 48-51.5 MJ/Sm3, Inerts <7%, N2 <5% Outline details of Primary separation processing -

Scenes from Aboard the Frigate HMCS Dunver, 1943-1945

Canadian Military History Volume 10 Issue 2 Article 6 2001 Through the Camera’s Lens: Scenes from Aboard the Frigate HMCS Dunver, 1943-1945 Cliff Quince Serge Durflinger University of Ottawa, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Quince, Cliff and Durflinger, Serge "Through the Camera’s Lens: Scenes from Aboard the Frigate HMCS Dunver, 1943-1945." Canadian Military History 10, 2 (2001) This Canadian War Museum is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Quince and Durflinger: Scenes from Aboard the HMCS <em>Dunver</em> Cliff Quince and Serge Durflinger he Battle of the Atlantic was the the ship's unofficial photographer until Tlongest and most important February 1945 at which time the navy maritime campaign of the Second World granted him a formal photographer's War. Germany's large and powerful pass. This pass did not make him an submarine fleet menaced the merchant official RCN photographer, since he vessels carrying the essential supplies maintained all his shipboard duties; it upon which depended the survival of merely enabled him to take photos as Great Britain and, ultimately, the he saw fit. liberation of Western Europe. The campaign was also one of the most vicious and Born in Montreal in 1925, Cliff came by his unforgiving of the war, where little quarter was knack for photography honestly. -

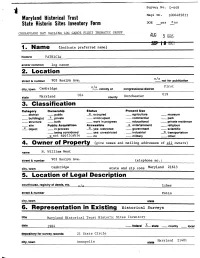

6. Representation in Existing Historical Surveys

Survey No. D-648 Magi No. 1006485833 Maryland Historical Trust State Historic Sites Inventory Form DOE _ye s x no CHESAPEAKE BAY SAILING LOG CANOE FLEET THEMATIC GROUP 4UG 5 SEP 18 I (indicate preferred name) historic PATRICIA and/or common log canoe 2. Location n/a street & number 903 Roslyn Ave. not for publication n/a .... First city, town Cambridge vicinity of congressional district 019 state Maryland °24 county Dorchester 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum building(s) x private unoccupied commercial park Structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible x entertainment religious x object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial x transportation x not applicable . no military other: 4. Owner Of Property (give names and mailing addresses of all owners) name H. William West street & number 903 Ave. telephone no.: city, town Cambridge state and zip code Maryland 21613 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. / a liber street & number folio city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Historical surveys title_______Maryland Historical Trust Historic Sites Inventory______ date 1984 federal 2^_ state county __ local depository for survey records 21 State Circle Maryland 21401 city, town Annapolis state 7. Description survey NO. ^J * Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered n/^original site good ruins js_ altered moved date of move fair unexposed Prepare bot& {a summary paragraph and a general description of the resource and its various elements as it exists today. PATRICIA is a 27'4" sailing log canoe in the racing fleet. -

London Southend Airport (LSA) Proposal to Re-Establish Controlled Airspace in the Vicinity of LSA

London Southend Airport (LSA) Proposal to Re-establish Controlled Airspace in The Vicinity Of LSA Airspace Change Proposal Management in Confidence London Southend Airport (LSA) Proposal to Re-establish Controlled Airspace in The Vicinity Of LSA Document information London Southend Airport (LSA) Proposal to Re-establish Document title Controlled Airspace in The Vicinity Of LSA Authors LSA Airspace Development Team and Cyrrus Ltd London Southend Airport Southend Airport Company Ltd Southend Airport Produced by Southend on Sea Essex SS2 6YF Produced for London Southend Airport X London Southend Airport T: X Contact F: X E: X Version Issue 1.0 Copy Number 1 of 3 Date of release 29 May 2014 Document reference CL-4835-ACP-136 Issue 1.0 Change History Record Change Issue Date Details Reference Draft A Initial draft for comment Draft B Initial comments incorporated – Further reviews Draft C 23 May 2014 Airspace Development Team final comments Final 27 May 2014 Final Review Draft D Issue 1.0 29 May 2014 Initial Issue CL-4835-ACP-136 Issue 1.0 London Southend Airport 1 of 165 Management in Confidence London Southend Airport (LSA) Proposal to Re-establish Controlled Airspace in The Vicinity Of LSA Controlled Copy Distribution Copy Number Ownership 1. UK Civil Aviation Authority – Safety and Airspace Regulation Group 2. London Southend Airport 3. Cyrrus Ltd Document Approval Name and Organisation Position Date signature X London Southend X 27 May 2014 Airport London Southend X X 27 May 2014 Airport London Southend X X 29 May 2014 Airport COPYRIGHT © 2014 Cyrrus Limited This document and the information contained therein is the property Cyrrus Limited.