Boatbuilding History of St. Augustine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2020 Volume XCVI Number 7

July 2020 Volume XCVI Number 7 Commodore’s Reports Race Results Tennis Fleet New Members July • August 2020 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY JULY 2 3 4 GALLEY WINDOW BAR RESUMES DECKHANDS LOCKER 1 HOURS NORMAL OPERATING HOURS (JULY 1) Contact Margaret Peebles Bulkhead Race Federal Holiday HAPPY 4th THURS & FRI 4-9p SAT 12-6p at (808) 342-1037 or email Mon-Fri Open 4p Dinghy Race SUNDAY 12-7p Sat Open 10a [email protected] 6p Sharp Start Sun Open 9a (Subject to Change) to make an appointment. 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Deckhands Meeting 6p CG #14 6:30p- TBD Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start ORF Singlehanded CG #17 6:30p - TBD 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Classboat H Mooring 6p F & P 6:30p Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race IRF B-3 6p Sharp Start 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Membership 6p Fleet Ops 6p Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start JR Sailing Session 4 Begins 26 27 28 29 30 31 OFFICE HOURS WED-SUN Classboat B Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 9a-4p BOD 7p 6p Sharp Start (Subject to Change) SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY August BAR HOURS OFFICE HOURS 1 WED-SUN Mon-Fri Open 4p 9a-4p Sat Open 10a Sun Open 9a (Subject to Change) 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Deckhands Meeting 6p CG #14 6:30p- TBD Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start CG #17 6:30p - TBD 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Mooring 6p F & P 6:30p Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Admissions Day Membership 6p Fleet Ops 6p Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 _____________________ ___________________ Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 30 31 BOD 7p 6p Sharp Start RED = KYC Meeting BLUE = KYC Event / Racing GREEN = Deckhands Locker PURPLE= Holidays Black=Yoga /Revised Hours On the cover: Puanani at anchor in Waimea Bay. -

Wooden Boat Building

WOODEN BOAT BUILDING Since 1978, students in the Wooden Boat Building Program at The Landing School have learned to create boats from scratch, producing functional art from plans created by professional yacht designers. As a program graduate, you will perfect skills that range from woodworking and composite fabrication to installing the latest marine systems – equipping you to start your own shop, build your own boat, crew a ship or become a master artisan. Study subjects include: How You’ll Learn Joinery & Refitting Your classwork will combine formal lectures and field trips with hands-on Modern Boat Building projects. Students are assigned to boat-specific teams, working together Techniques: Cold Molding Rigging under highly experienced instructors to learn quality and efficiency in every step of boat construction: lofting, setup, planking, fairing, joinery, spars, Professional Shop Practices rigging, finish work and, ultimately, sea trials. Proper Training in Boat projects are selected not only to match the interests of each team, but Modern & Traditional Tools to teach skills currently in demand within the marine industry. Typical builds include mid-sized boats such as the Flyfisher 22 powerboat, or a sailboat Traditional Boat Building such as the Haven 12½. To round out your skills, you may also construct Techniques: elements of smaller boats, such as a Peapod or Catspaw. Lapstrake Planking Visit us online at landingschool.edu Earning Your Diploma or Degree Additional occupations include: To earn a diploma in the Wooden Boat Building Program, you must attend The Landing School full time for two semesters (about eight months) and Boat Crewing meet all graduation criteria. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

500 Years of Maritime History

500 Years of Maritime History By the mid-sixteenth century King Philip of Spain felt an acute need to establish a coastal stronghold in the territory he claimed as “La Florida," a vast expanse including not only present-day Florida but most of the continent. The Atlantic coast of present-day Florida was strategically important for its proximity to Spanish shipping routes which followed the Gulf Stream and annually funneled the treasures of Philip's New Above: Traditional Spanish New World shipping routes. World empire back to Spain. The two biggest threats to this transfer of wealth were pirate attacks and shipwrecks. A military outpost on the Florida coast could suppress piracy while at the same time serve as a base for staging rescue and salvage operations for the increasing number of ships cast away on Florida's dangerous shoals. With these maritime goals in mind, the King charged Don Pedro Menéndez de Avilés with the task of establishing a foothold on Florida's Atlantic coast. Before leaving Spain, word reached the Spanish court that a group of French protestants had set up a fledgling colony in the region, and Menéndez' mission was altered to include the utter destruction of the French enterprise, which represented not only heresy but a direct threat to Spain's North American hegemony. The French Huguenots, led by René de Laudonnière, had by 1563 established Fort Caroline at the bank of the River of May (present-day St. Johns River at Jacksonville, north of St. Augustine). Early in 1565, France's King Charles sent Jean Ribault to re-supply and assume command of the Fort. -

TEST for VESSEL STATUS Lozman V. City Of

CASE COMMENT IF IT LOOKS LIKE A VESSEL: THE SUPREME COURT’S “REASONABLE OBSERVER” TEST FOR VESSEL STATUS Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, 133 S. Ct. 735 (2013) David R. Maass∗ What is a vessel? In maritime law, important rights and duties turn on whether something is a vessel. For example, the owner of a vessel can limit his liability for damages caused by the vessel under the Limitation of Shipowners’ Liability Act,1 and an injured seaman who is a member of the crew of a vessel can claim remedies under the Jones Act.2 Under the general maritime law, a vendor who repairs or supplies a vessel may acquire a maritime lien over the vessel.3 In these and other areas, vessel status plays a crucial role in setting the limits of admiralty jurisdiction. Clear boundaries are important because with admiralty jurisdiction comes the application of substantive maritime law—the specialized body of statutory and judge-made law that governs maritime commerce and navigation.4 The Dictionary Act5 defines “vessel” for purposes of federal law. Per the statute, “[t]he word ‘vessel’ includes every description of watercraft or other artificial contrivance used, or capable of being used, as a means of transportation on water.”6 The statute’s language sweeps broadly, and courts have, at times, interpreted the statute to apply even to unusual structures that were never meant for maritime transport. “No doubt the three men in a tub would also fit within our definition,” one court acknowledged, “and one probably could make a convincing case for Jonah inside the whale.”7 At other times, however, courts have focused on the structure’s purpose, excluding structures that were not designed for maritime transport.8 In Stewart v. -

Website Address

website address: http://canusail.org/ S SU E 4 8 AMERICAN CaNOE ASSOCIATION MARCH 2016 NATIONAL SaILING COMMITTEE 2. CALENDAR 9. RACE RESULTS 4. FOR SALE 13. ANNOUNCEMENTS 5. HOKULE: AROUND THE WORLD IN A SAIL 14. ACA NSC COMMITTEE CANOE 6. TEN DAYS IN THE LIFE OF A SAILOR JOHN DEPA 16. SUGAR ISLAND CANOE SAILING 2016 SCHEDULE CRUISING CLASS aTLANTIC DIVISION ACA Camp, Lake Sebago, Sloatsburg, NY June 26, Sunday, “Free sail” 10 am-4 pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) Lady Bug Trophy –Divisional Cruising Class Championships Saturday, July 9 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 10 11 am ADK Trophy - Cruising Class - Two sailors to a boat Saturday, July 16 10 am and 2 pm * (See note Below) Sunday, July 17 11 am “Free sail” /Workshop Saturday July 23 10am-4pm Sailing Canoes will be rigged and available for interested sailors (or want-to-be sailors) to take out on the water. Learn the techniques of cruising class sailing, using a paddle instead of a rudder. Give it a try – you’ll enjoy it! (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club) . Sebago series race #1 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) July 30, Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #2 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. 6 Saturday, 10 a.m. Sebago series race #3 - Cruising Class (Sponsored by Sheepshead Canoe Club and Empire Canoe Club) Aug. -

Another Successful Summer by Nick Mansbach T’S Been So Long Since I’Ve Written but the Clubs to Spend a Fun Filled Day on the Bay

COCONUT GROVE SAILING CLUB channelthe serving the community since 1945 OCTOBER 2008 Another Successful Summer by Nick Mansbach t’s been so long since I’ve written but the clubs to spend a fun filled day on the bay. At about sailing world has been busy, busy, busy! I’ll start 10am we loaded all the parents and all the kids by telling you about this year’s summer camp, on all different kinds of club boats; we had Prams, I Opti’s and Sunfish along with which was a tremendous success. This year we all our powerboats (including had a whopping 213 kids our good ‘ol Pontoon boat) and attending! The reason for headed out to the Dinner Key this dramatic increase was sandbar. If you’ve never seen a our staff; they were by Grandmother sailing in a Pram far the best I’ve ever had with their Granddaughter, let the opportunity to work me tell you it’s quite the sight! with, so thank you to all Once we arrived at the Sandbar the instructors and CIT’s everyone got an opportunity to (counselors in training) sail on all the different boats with who made this possible. their brothers, sisters, moms and We also had our second dads and instructors and CIT’s annual “Parent & kids fun day” which also turned as well. out to be a big hit. We started that morning with During our first hour there we were all treated to approximately 25 parents and about 40 kids looking something pretty cool, the Geico Racing Teams continued on page 8 COMMODORE’S REPORT opefully, by the time you get to read this, autumn will be starting to take hold, and the Hlong hot summer will just about be history. -

Coconut Grove Waterfront Master Plan

COCONUT GROVE WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN ERA / Curtis Rogers / ConsulTech / Paul George Ph.D. Agenda • City's Vision & Community Input • Framework Concepts • December 2006 Schemes • Draft Final Plan – Waterfront Open Space – Civic Core – Maritime Amenities & Facilities – Event Strategy – Roadway Strategy • Next Steps CITY'S VISION & COMMUNITY INPUT City's Vision & Requirements Vision for Coconut Grove's Waterfront • A coastal recreational park • Human scale • Public open space • Connectivity for the pedestrian realm • Waterfront promenades • Diverse open spaces • An active park • Sensitive environmental spoil island connections (real or visual) Requirements • A Plan that reflects the growth and desires of the community • An overhaul of the mooring fields to comply with the Federal Department of Environmental Protection • Spoil islands rehabilitation: cleaned of exotic plants, replanted with native species and redesigned for public access - Coconut Grove Waterfront & Spoil Islands Request for Qualifications Community Input 2004 Peacock Park Charrette • Lead by Friends of Peacock Park to develop a vision for the future of the Peacock Park • Charrette concepts: – Enhance landscaped open spaces – Minimal service parking only – Trim and "window" mangroves – Connection to spoil islands – Tie into local history – Redesign street frontage and articulate entrances – Redesign and seek alternative uses for Glass House – Outdoor cultural facility (amphitheater, waterfront plaza) – Hardcourts ok, no expansion Public Process • Stakeholder Input – May 2005 -

Boatbuilding Materials for Small-Scale Fisheries in India

BAY OF BENGAL PROGRAMME BOBP/WP/9 Development of Small-Scale Fisheries (G CP/RAS/040/SWE) BOATBUILDING MATERIALS FOR BOBP/WP/9 SMALL-SCALE FISHERIES IN INDIA Executing Agency: Funding Agency: Food and Agriculture Organisation Swedish International of the United Nations Development Authority Development of Small-Scale Fisheries in the Bay of Bengal Madras, India, October 1980 PREFACE This paper summaries a study on the availability and prices of materials used to construct the hulls of fishing craft for the important small-scale fisheries of the East Coast of India. The paper should be of interest to development planners, legislators and administrators. Builders of fishing craft, suppliers of materials, and owners and prospective owners of fishing craft may also find useful the information on trends in prices and availability of boatbuilding materials and the possibilities of alternative materials. The study covered the following boatbuilding materials: timber for kattumarams and boats; fibre-reinforced plastics; ferrocement; steel; and aluminium, which is used forsheathing wooden hulls and is also a construction material in its own right. The study was carried out by Matsyasagar Consultancy Services Private Limited under contract to the Programme for the Development of Small-Scale Fisheries in the Bay of Bengal, GCP/ RAS/040/SWE (usually abbreviated to the Bay of Bengal Programme). The Programme is executed by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and funded by the Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA). The main aims of the Bay of Bengal Programme are to develop and demonstrate technologies by which the conditions of small-scale fishermen and the supply of fish from the small-scale sector may be improved, in five of the countries bordering the Bay of Bengal — Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. -

Sail Area Math by Jim Michalak BACKGROUND

Sail Area Math by Jim Michalak BACKGROUND... If you look at the picture below of the sail rig of Mayfly12 you will see on the sail some (fuzzy) writing (that didn't scan well) that says "55 square feet" to the left of a small circle that represents the center of that area (honest). Fig 1 The center of that area is often called a "centroid" and you will see it is placed more or less directly above the center of the leeboard's area. That is very important. As you might imagine a shallow flat hull like this with a deep narrow leeboard wants to pivot around that leeboard. If the forces of the sail, which in a very general way can be centered at the sail's centroid, push sideways forward of the leeboard, the boat will tend to fall off away from the wind. You should be able to hold the boat on course with the rudder but in that case the rudder will have "lee helm" where you have to use the rudder to push the stern of the boat downwind. The load on the rudder will add to the load of the leeboard. Sort of a "two wrongs make a right" situation and generally very bad for performance and safety in that if you release the tiller as you fall overboard the boat will bear off down wind without you. If the centroid is aft of the leeboard you will have "weather helm", a much better situation. The rudder must be deflected to push the stern towards the wind and the force on it is subtracted from the load on the leeboard. -

Owner'smanual

OWNER'SMANUAL Harbor Road, Mattapoisett Massachusetts 02739 617-758-2743 * DOVEKIE OWNERS MANUAL INDEX X Subject Page 1. General .................................................................. .2 2. Trailers & Trailering.. .............................................. 3 3. Getting Under Way ................................................ .5 4. Trim & Tuning.. .................................................... -7 5. Reefing ................................................................. 11 6. Putting Her to Bed.. ............................................. .12 7. Rowing & Sculling.. ........ .................................... .13 8. Anchors & Anchoring .......................................... .15 9. Safety.. ................................................................. 16 10. Cooking, Stowage, & Domestic Arts.. ................... .17 11. Maintenance & Modifications ............................... .18 12. Heaving To ......................................................... ..2 0 13. Help & Information ............................................. ..2 1 14. Cruising checklist.. ................................................ .22 15. Riging Lid.. ......................................................... 23 General Revision 03/94 ’ j Page 2 1. GENERAL: There are a number of “immutable” rules concerning DOVEKIE that best fall in this section. Also, this manual includes some subjective thoughts, as well as objective instructions. We recommend you follow them until you thoroughly understand the boat and’its workings. Then -

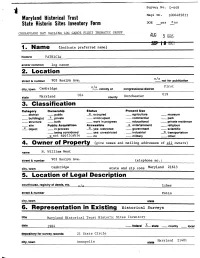

6. Representation in Existing Historical Surveys

Survey No. D-648 Magi No. 1006485833 Maryland Historical Trust State Historic Sites Inventory Form DOE _ye s x no CHESAPEAKE BAY SAILING LOG CANOE FLEET THEMATIC GROUP 4UG 5 SEP 18 I (indicate preferred name) historic PATRICIA and/or common log canoe 2. Location n/a street & number 903 Roslyn Ave. not for publication n/a .... First city, town Cambridge vicinity of congressional district 019 state Maryland °24 county Dorchester 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum building(s) x private unoccupied commercial park Structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible x entertainment religious x object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial x transportation x not applicable . no military other: 4. Owner Of Property (give names and mailing addresses of all owners) name H. William West street & number 903 Ave. telephone no.: city, town Cambridge state and zip code Maryland 21613 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. / a liber street & number folio city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Historical surveys title_______Maryland Historical Trust Historic Sites Inventory______ date 1984 federal 2^_ state county __ local depository for survey records 21 State Circle Maryland 21401 city, town Annapolis state 7. Description survey NO. ^J * Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered n/^original site good ruins js_ altered moved date of move fair unexposed Prepare bot& {a summary paragraph and a general description of the resource and its various elements as it exists today. PATRICIA is a 27'4" sailing log canoe in the racing fleet.