D EGYPT UPDATE NUMBER 28 D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Amal Mahmoud Salem's CV

FACULTY FULL NAME AMAL MAHMOUD HUSSEIN SALEM POSITION Professor of Bioinformatics and Molecular Virology Personal Data Nationality |Egyptian Date of Birth |12/1/1968 Department |Biology Official Email | [email protected] Language Proficiency Language Read Write Speak Arabic Excellent Excellent Excellent English Excellent Excellent Excellent French Excellent Good Very good Academic Qualifications (Beginning with the most recent) Date Academic Degree Place of Issue Address 1990 BSc Cairo University Egypt 1994 MSc Cairo University-ORSTOM Egypt-France 2001 PhD Cairo University-CIRAD Egypt-France PhD, Master or Fellowship Research Title: (Academic Honors or Distinctions) PhD Biological and molecular characteristics of maize yellow stripe virus and its relationship with the leafhopper vector Master Characterization and serology of the leafhopper-borne maize yellow stripe tenuivirus in Egypt Fellowship Virus characterization and diagnosis, ORSTOM (Egypt-French project) Fellowship Molecular characterization and Bioinformatics analysis of MYSV (CIRAD Montpellier, France) Fellowship Bioinformatics analysis of CTV and its population structure (University of Davis-California, USA) Professional Record: (Beginning with the most recent) Job Rank Place and Address of Work Date Professor Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal Saudi Arabia 25-9-2019 Univ. Associate trainer certified by IBCT 19-9-2018 Associate professor Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal Saudi Arabia 3-1-2017 Univ. Head of Bioinformatics Dept. GEBRI-Sadat Univ. Egypt 2015-2016 Director manger Alkhwarizmi Center for Egypt 2013 Bioinformatics, Egypt 1 Associate professor GEBRI-Sadat Univ. Egypt 2012 Assistant professor GEBRI-Sadat Univ. Egypt 2005 Lecturer GEBRI-Sadat Univ. Egypt 2002 Post-Doc fellow UC-Davis USA 2001 Assistant lecturer Plant protection ins. Ministry of Egypt 1998 agric. -

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio Between the US and Syria

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Beau Bothwell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Song, State, Sawa: Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell This dissertation is a study of popular music and state-controlled radio broadcasting in the Arabic-speaking world, focusing on Syria and the Syrian radioscape, and a set of American stations named Radio Sawa. I examine American and Syrian politically directed broadcasts as multi-faceted objects around which broadcasters and listeners often differ not only in goals, operating assumptions, and political beliefs, but also in how they fundamentally conceptualize the practice of listening to the radio. Beginning with the history of international broadcasting in the Middle East, I analyze the institutional theories under which music is employed as a tool of American and Syrian policy, the imagined youths to whom the musical messages are addressed, and the actual sonic content tasked with political persuasion. At the reception side of the broadcaster-listener interaction, this dissertation addresses the auditory practices, histories of radio, and theories of music through which listeners in the sonic environment of Damascus, Syria create locally relevant meaning out of music and radio. Drawing on theories of listening and communication developed in historical musicology and ethnomusicology, science and technology studies, and recent transnational ethnographic and media studies, as well as on theories of listening developed in the Arabic public discourse about popular music, my dissertation outlines the intersection of the hypothetical listeners defined by the US and Syrian governments in their efforts to use music for political ends, and the actual people who turn on the radio to hear the music. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

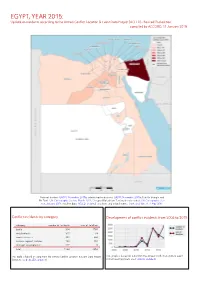

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

To Whom Do Minbars Belong Today?

Besieging Freedom of Thought: Defamation of religion cases in two years of the revolution The turbaned State An Analysis of the Official Policies on the Administration of Mosques and Islamic Religious Activities in Egypt The report is issued by: Civil Liberties Unite August 2014 Designed by: Mohamed Gaber Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 14 Al Saraya Al Kobra St. First floor, flat number 4, Garden City, Cairo, Telephone & fax: +(202) 27960197 - 27960158 www.eipr.org - [email protected] All printing and publication rights reserved. This report may be redistributed with attribution for non-profit pur- poses under Creative Commons license. www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Amr Ezzat: Researcher & Officer - Freedom of Religion and Belief Program Islam Barakat and Ibrahim al-Sharqawi helped to compile the material for this study. The Turbaned State: An Analysis of the Official Policies on the Administration of Mosques and Islamic Religious Activities in Egypt Summary: Policies Regulating Mosques: Between the Assumption of Unity and the Reality of Diversity Along with the rapid political and social transformations which have taken place since January 2011, religion in Egypt has been a subject of much contention. This controversy has included questions of who should be allowed to administer mosques, speak in them, and use their space. This study observes the roots of the struggle over the right to administer mosques in Islamic jurisprudence and historical practice as well as their modern implications. The study then moves on to focus on the developments that have taken place in the last three years. The study describes the analytical framework of the policies of the Egyptian state regarding the administration of mosques, based on three assumptions which serve as the basis for these policies. -

Egypt Weekly Newsletter November 2014, 2Nd Quarter

EGYPT WEEKLY NEWSLETTER November, 2014 (2nd QUARTER) CONTENT 1. Political Overview………..........01 2. Economic Overview……..….…..02 3. Finance..…………………………..….05 4. IT & Telecom………………………..05 5. Energy……………………………….… 06+ 6. Agriculture.…..……..………………07 7. Building Materials……..…………08 8. Real Estate.…………..……..……...08 9. Laws & Regulations…..…………. 08 10. Hot Issue……………………….……09 Compiled by Thai Trade Center, Cairo POLITICAL OVERVIEW Parliamentary polls to be held before end of March, says El-Sisi Source: Egypt Impendent, November 13, 2014 Egypt's president Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi said in a meeting with a delegation of American businesspeople on Monday that Egyptian parliamentary elections will take place before the end of March 2015. The statement is the closest estimate given by an official regarding the date of the polls, which has been shrouded in mystery for quite some time. A statement by presidential spokesman Alaa Youssef said El-Sisi mentioned that the third objective of Egypt's transitional roadmap, following a new constitution and presidential elections, "will be achieved before the International Economic Summit which Egypt will host in the first quarter of 2015." The delay of a date for elections was criticised by politicians and observers who have argued the delay is unconstitutional; Egypt's January 2014 constitution says electoral procedures for parliamentary elections must commence after 6 months following the constitution’s ratification. The meeting included representatives from the Egypt-US Business Council and the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt. Egypt Prime Minister Ibrahim Mahlab attended the meeting along with many members of cabinet including the industry and trade, planning, investment, electricity and renewable energy and petroleum ministries. -

11. Egypt's Missing Millions

BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION RADIO 4 TRANSCRIPT OF “FILE ON 4” – “EGYPT’S MISSING MILLIONS” CURRENT AFFAIRS GROUP TRANSMISSION: Tuesday 15th March 2011 2000 - 2040 REPEAT: Sunday 20th March 2011 1700 - 1740 REPORTER: Fran Abrams PRODUCER: Ian Muir-Cochrane EDITOR: David Ross PROGRAMME NUMBER: 11VQ4873LHO 1 THE ATTACHED TRANSCRIPT WAS TYPED FROM A RECORDING AND NOT COPIED FROM AN ORIGINAL SCRIPT. BECAUSE OF THE RISK OF MISHEARING AND THE DIFFICULTY IN SOME CASES OF IDENTIFYING INDIVIDUAL SPEAKERS, THE BBC CANNOT VOUCH FOR ITS COMPLETE ACCURACY. “FILE ON 4” Transmission: Tuesday 15th March 2011 Repeat: Sunday 20th March 2011 Producer: Ian Muir-Cochrane Reporter: Fran Abrams Editor: David Ross ACTUALITY IN TAHRIR SQUARE ABRAMS: I’m standing in Tahrir Square, which was the focus for the protest which led to the fall of the President Hosni Mubarak here in Egypt last month. The atmosphere here today’s really quite cheerful. There’s a huge crowd, there’s a sea of flags, Egyptian flags everywhere and the people here really feel that they’ve got quite a lot to celebrate. But in tonight’s File on 4 I’m going to be investigating an issue which is still causing a rising sense of anger here is Egypt - corruption. ALBARDEI: Egypt was really unfortunately stolen, a lot of the wealth was stolen and this is a very poor country. I couldn’t see if a taxi driver that had a car accident should go to jail and somebody that stole a billion pounds should go scot free. ABRAMS: Since Hosni Mubarak was forced out, Cairo’s been awash with rumours about stolen money. -

“Jesters Do Oft Prove Prophets” William Shakespeare King Lear (Act 5, Scene 3)

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION “Jesters do oft prove prophets” William Shakespeare King Lear (Act 5, Scene 3) During Medieval times, kings kept jesters for amusement and telling jokes. Jesters played the role of both entertainers and advisers, sarcastically mocking reality to entertain and amuse. The jester’s unique position in the court allowed him to tell the king the truth upfront that no one else dared to speak, under the cover of telling it as a jest (Glenn, 2011). In this sense, contemporary political satire has given birth to many modern-day jesters, one of the most famous worldwide being Jon Stewart, and on a more local scale but also gaining widespread popularity, Bassem Youssef. Political satire is a global genre. It dates back to the 1960s, originating in Britain, and has now become transnational, with cross-cultural flows of the format popular and flourishing across various countries (Baym & Jones, 2012). The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report are examples of popular political satire shows in the United States. Both shows have won Emmy awards and Jon Stewart was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world. Research on political satire shows that it does not have unified effects on its audiences. Different types of satire lead to distinct influences on viewers (Baumgartner & Morris, 2006; Baumgartner & Morris, 2008; Holbert et al, 2013; Lee, 2013). Moreover, viewers of different comedy shows are not homogeneous in nature. The Daily Show's audience was found to be more politically interested and knowledgeable than Leno and Letterman viewers (Young & Tisinger, 2006). -

ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY from EGYPT's ARAB SPRING by JULES

ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY FROM EGYPT’S ARAB SPRING by JULES M. SCALISI A Capstone Project submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers-The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES under the direction of Dr. Michael Rossi Approved by: ____________________________________ Dr. Michael Rossi, signed December 31, 2012 Camden, New Jersey January 2013 i ABSTRACT OF THE CAPSTONE ISLAMIC DEMOCRACY FROM EGYPT’S ARAB SPRING By JULES M. SCALISI Capstone Director Dr. Michael Rossi The collective action by Arabs throughout North Africa, the Middle East, and Southwest Asia has been a source of both joy and anxiety for the western world. When Tunisians took to the streets on December 18, 2010 they could not have imagined how the chain of events they had just begun would change the world forever. Arab Spring has granted new found freedoms to citizens in that part of the world. Many of these nations have seen new, democratically elected governments take hold. As the West rejoices for freedom’s victories, we cannot help but wonder how the long term changes in each country will impact us. With this new hope comes a sense of uncertainty. Is a democratically elected government compatible with the cultures and traditions of the Muslim world? Is there concern that a democratically elected head of state will resort to the type of strongman politics which results in a blended, or hybrid regime that has become common to the region? Will the wide-spread animosity that many Arabs feel ii against the United States carry over into politics? My aim with this project is to apply these questions and others to a single nation, as I examine the Egyptian Arab Spring movement. -

April 2020 - ISSUE 37 INVEST-GATE

MARKET WATCH BY DINA EL BEHIRY POWERED BY POWERED BY MARKET WATCH REAL ESTATE INDUSTRY ACCOMPLISHMENTS NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR URBAN DEVELOPMENT 2052 REVENUE EXPECTATIONS IN 2020 TARGET New Urban Communities doubling urbanization rate Authority's (NUCA) target % % EGP bn HOUSING PROJECTS INFRASTRUCTURE Social Housing & Mortgage Finance Fund Offers New Units Government to Develop Roads Area Payment Period Up to 150 meters per unit Up to 20 years No. of Roads 197 Payment Method Minimum Installment Installments EGP 3,100 Roads’ Length 840 kilometers (km) Location Beit El Watan Project (7th Phase) Giza, Qaluobiya, Mounifya, Dakhlya, Beheira, Kafr El Sheikh, Sharqiyah, Gharbia, Damietta, Beni Suef, Fayoum & Minya New Housing Units Government to Construct New Roads Number of Cities Location 5 Sheikh Zayed, New Cairo, 6th of October, New Damietta & New Mansoura No. of Roads 2,652 New Residential Plots Roads’ Length 6,587 km Number of Cities Location 8 Sheikh Zayed, 6th of October, El Obour, New Damietta, Badr, New Cairo, El Shorouk Investments & Sadat EGP 12.7 bn Delivery Time Government to Implement New Projects in Fiscal Year (FY) 2019/20 2021-2022 Number of Projects Location Sohag, Beni Suef, Minya, 202 Assiut & Aswan Egyptian government to develop ring road Target Investments Developing villages EGP 944 mn with investments exceed EGP 7 bn Sources: Cabinet, Ministry of Housing, Ministry of Planning, Monitoring and Administrative Reform (MPMAR) & Social Housing and Mortgage Finance Fund. 2 aprIL 2020 - ISSUE 37 INVEST-GATE LAND OFFERING NUCA Offers Ministry of Housing Offers New Plots No. of New Plots Location Badr, Sadat, New Minya, 10th of Ramadan, 15th of May, 30 New Borg El Arab, New Beni Suef, New Assiut & New Aswan 25 5 Target New housing projects New Assiut East Port Said No. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Maye Kassem. 1999. In the Guise of Democracy: Governance in Contem- porary Egypt (London: Ithaca Press); Eberhard Kienle. 2001. A Grand Delusion: Democracy and Economic Reform in Egypt (London: I. B. Tau- ris); Eva Bellin. 2002. Stalled Democracy: Capital, Labor, and the Paradox of State- Sponsored Development (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press); Jason Brownlee. 2007. Authoritarianism in an Age of Democratization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press); Lisa Blaydes. 2011. Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt (Cambridge: Cambridge Uni- versity Press); Ellen Lust-Okar. 2004. “Divided They Rule: The Manage- ment and Manipulation of Political Opposition,” Journal of Democracy 36(2): 139– 56. 2. Barrington Moore. 1966. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Boston: Beacon); Charles Moraz. 1968. The Triumph of the Middle Class (New York: Anchor); Eric Hobsbawm. 1969. Industry and Empire (Har- mondsworth: Penguin). 3. Bellin. 2002. 4. Nazih Ayubi. 1995. Over-Stating the Arab State: Politics and Society in the Middle East (London: I. B. Tauris). 5. Samuel Huntington. 1991. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press), p. 67. 6. Ray Bush. 2012. “Marginality or Abjection? The Political Economy of Pov- erty Production in Egypt,” in Marginality and Exclusion in Egypt, ed. Ray Bush and Habib Ayeb (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press), p. 66. 7. Bellin. 2002. 8. Amr Adly. 2009. “Politically- Embedded Cronyism: The Case of Egypt,” Busi- ness and Politics 11(4): 1– 28. 9. Bellin. 2002. 10. Adly. 2009. 11. The only Policies Secretariat meeting that Gamal Mubarak missed since the establishment of the Secretariat in 2002 was in March 2010 when he was accompanying his father in Germany for treatment. -

Dear Sir, I Am an Energetic, Experienced Academic

Dr-Sameh El-Sayed Mohamed Yehia Dear Sir, I am an energetic, experienced academic doctor aspiring to a challenging position as an Assistant Professor in (Civil Engineering-Structural) where I can apply my abilities and demonstrate my qualifications, motivation, enthusiasm and excellent communication skills. I have been teaching under-graduate students "Structure Analysis", "Characteristics and Test of Materials" and "Design of Reinforced Concrete Structures" courses in El-Shorouk Academy - Higher Institute of Engineering (Egypt), as well as supervision on graduation projects and teaching AutoCAD and SAP to graduated engineers in few training center in additional to teaching under-graduate students "Structure Analysis","Characteristics and Test of Materials" and "Inspection and non- destructive testing" and "Maintenance and Repairing of Structures" courses in El- Obour Higher Institute for Engineering and Technology (Egypt) and "Structure Analysis" and "Civil Engineering" at Faculty of Engineering, Misr International University (MIU). I have also more than ten years of working experiences in the field of structural designs, executive and workshop drawings. I think that my education, training and experiences make me a distinctive candidate for employment with your available position. Please, find my resume which represents my qualifications. Also, you may contact me for additional information. Thank You for Reading My C.V Best Regards, Dr. Sameh El-Sayed Mohamed Yehia Page 1 of 6 Dr-Sameh El-Sayed Mohamed Yehia CURRICULUM VITAE Personal Data: Name: Sameh El-Sayed Mohamed Yehia. Date of birth: 11/1/1984. Nationality: Egyptian. Marital Status: Married. Military status: Permanent Exemption. Tel Mobile: +201000256520. Tel: +202/23828460. Address: 76 Ali Amein St, Nasr City, Cairo, Egypt. -

President's Report-18.Indd 1 1/28/09 11:52:40 AM President's Report-18.Indd 2 1/28/09 11:52:43 AM Table of Contents

PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2007-2008 President's Report-18.indd 1 1/28/09 11:52:40 AM President's Report-18.indd 2 1/28/09 11:52:43 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Letters 6 Features 14 Public Lectures 20 Highlights 24 Sponsored Programs 28 Financials 30 President’s Club 38 Board of Trustees President's Report-18.indd 3 1/28/09 11:52:44 AM This year we witnessed the realization of what could be described as the single biggest achievement in AUC’s history: after 10 years of planning and construction, the university successfully relocated to its new campus in New Cairo. It is fitting that this monumental relocation occurred on the eve of the university’s 90th anniversary, reminding us that the new campus is not just a new beginning, it also represents the continuation of a rich legacy spanning nearly a century. While the completion of the campus and the complicated logistics of the move presented us with multiple challenges — not atypical of an undertaking of this magnitude — they also created a wealth of opportunities that will propel AUC to a new level of excellence. As we are confronted with new challenges, we have a rare opportunity to re-examine all areas of operation, rethinking and refining many of our systems and programs. Yet, the most exciting opportunities for the institution are still unfolding and will continue in the years to come. The building of the New Cairo Campus is about creating a world- class university from the inside out. The campus has given us the most modern facilities needed to create that university, but it is AUC’s dedicated faculty and quality students President’s Letter who have always been the guiding force behind its success.