LI a Lidaziay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deer Hunting with Dogs on the Quantock Hills in Somerset 2018/19 a Report by Somerset Wildlife Crime and Hounds Off

Deer Hunting With Dogs On The Quantock Hills In Somerset 2018/19 A Report by Somerset Wildlife Crime and Hounds Off HOUNDS OFF Protecting You From Hunt Trespass 1. Introduction 2 2. Background 3-4 3. Quantock Stag Hounds Fixture List 2018/19 5-6 4. National Trust 7-10 5. Forestry Commission 11-12 6. Other Landowners 13-14 7. Firearms 15-18 8. Biosecurity 19-20 9. Policing 21-24 10. Anti Social Behaviour, Threats & Assaults 25-26 11. Tracks & Rights Of Way 27-28 12. Road Safety 29-30 13. Cruelty Of Deer Hunting With Dogs 31-34 14. Public Outreach 35-36 15. How You Can Help This Campaign 37 16. Conclusions 38 17. From the Heart 39-40 Deer Hunting With Dogs On The Quantock Hills In Somerset 2018/19 A Report by Somerset Wildlife Crime and Hounds Off Closing in for the kill, 11/04/19. 1 Deer Hunting With Dogs On The Quantock Hills In Somerset 2018/19 A Report by Somerset Wildlife Crime and Hounds Off 1. Introduction 1.1 In response to requests from local residents, in August 2018 we (Somerset Wildlife Crime and Hounds Off) began a focused campaign to shine a light on modern day deer hunting with dogs. (1) 1.2 Throughout the 2018/19 hunting season the Quantock Stag Hounds (QSH) chased red deer with pairs of dogs plus the eyes, ears, binoculars, mobile phones and two-way radios of their supporters on horseback, motorbikes, quadbikes, four-wheel drives and on foot. 1.3 Deer were killed by running them to exhaustion and then shooting from close range. -

CATAIR Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA April 24, 2020 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes ............................................................................................................................................4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes .................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ............................................................................................. 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes.................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers .................................................................... 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ...................................................................................................................... 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers.................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure .............................................................................................................................. 30 PG05 – Scie nt if ic Spec ies Code .................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ..................................................................................................... -

90U0eum for Tbe Geat

— iRcport of tfte Cutator of Caunton €a0tle 90u0eum for tbe geat 1902. OINCE the last Report, a considerable amount of general ^ progress has been effected, especially with regard to the “ Walter Collection.” Endeavours have been made to aug- ment, as far as possible, the educational value of the specimens that have been dealt with. An increasing interest in the Museum is manifest, and it is gratifying to be able to record that the attendance of visitors, “including members, — during the year has greatly exceeded anything previously recorded, the total reaching 7,444 ; an in- crease over 1901 of 47 per cent. The following is a Table of the number of visitors to Taunton Castle Museum during the last ten years : Year. No. of Visitors. Year. No. of Visitors. 1893 5,539 1898 5,082 1894 5,317 1899 4,978 1895 4,964 1900 4,740 1896 4,610 1901 5,047 1897 5,236 1902 7,444 The greater part of the year has been occupied by work in connection with the large donation made in December, 1901, by Mr. W. W. Walter. Owing to the fact that arrangements were made for temporary assistance, etc., most of this work was accomplished before the Opening Ceremony, on May 21st. Every specimen—and there are some hundreds—was firstly cleaned, ])reservatives being applied and repairs effected where necessary. A large proportion of the objects have been tick- eted in white oil-paint; others were written on in indelible ink : Curator's Report. 63 neatly printed labels have been glued on to all fragments of pottery ; and other specimens were found better adapted for ‘ tie-on ’ labels. -

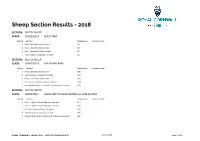

Sheep Section Results - 2018

Sheep Section Results - 2018 SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0312 AGED RAM Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (3) 2 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (4) 3 Miss T Cobbledick, Bude, Cornwall (2) 7 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (5) SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0313 SHEARLING RAM Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (10) 2 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (12) 3 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (11) 4 Mr S & Mrs G Renfree, Liskeard, Cornwall (20) 7 Mrs M A Heard & Mr G J Garland, Wiveliscombe, Somerset (15) SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0314 AGED EWE TO HAVE REARED A LAMB IN 2018 Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Miss A H & Mrs S Payne, Newquay, Cornwall (27) 2 Miss A H & Mrs S Payne, Newquay, Cornwall (28) 3 Miss J M Lapthorne, Plymouth, Devon (26) 4 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (23) 7 Mrs M A Heard & Mr G J Garland, Wiveliscombe, Somerset (24) ROYAL CORNWALL SHOW 2018 - SHEEP SECTION RESULTS 13 June 2018 Page 1 of 64 SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0315 SHEARLING EWE Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mr H Williams, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire (49) 2 Mrs M A Heard & Mr G J Garland, Wiveliscombe, Somerset (38) 3 Mr S & Mrs G Renfree, Liskeard, Cornwall (47) 4 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (34) 5 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (36) 6 Mr S & Mrs G Renfree, Liskeard, Cornwall (48) 7 Mr H Williams, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire (50) SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0316 RAM LAMB Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. -

Index 2001–2010

INDEX 2001–2010 Artley, Suzanne Bates, Julie KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS Lanolin for Healing. Sp09: 112 Restoring My Antique Spinning Wheel. Sp01: Sp Spring Athena, Star 84–87 Su Summer Quant, K. Su09: 82 Baxter, Clairelis F Fall W Winter Axtman, Wendy A Yarn to Remember. F03: 120 Cr crochet Spinning Cosmetic Puffs, K. F03: 82 Beal, Stephen H number of harnesses Baker, A. M. Nora Meets Milan. Su05: 120 K knit Spinning Memories. W10: 112 Becker, Libby Pw plain weave Bakriges, Jeannine Jane’s Half Gloves, K. W10: 94 RH rigid heddle Book Review. Coat of Many Scrumbles Beers, Julie Tw twill (Mapstone). Sp08: 20–21 In Spite of It All: Spinning with Multiple Compiler’s note: Sp05: 1–3 is a continuous Book Review. A Gathering of Lace (Swansen). Sclerosis. Su06: 38–40 reference; Sp05: 1, 3 contains intervening text W01: 19–20 Unspun Entrelac Button-Up Neck Warmer, K. Book Review. Handpaint Country (Potter). Sp10: 88 Sp03: 19 Bell, Paige Book Review. Sweaters from Camp (Detjen, Book Review. The Prairie Girl’s Guide to Life Author/Designer Index Swansen, and Williams). F03: 16 (Worick). Sp08: 23 Drafting Techniques: The Long and Short of Book Review. Runway Knits: 30 Fashion- Abrams, Charlene It. Su10: 64–67; correction, F10: 4 Forward Designs (Karapetyan). F07: 16 Handspun Mitered-Square Sweater, K. Su03: Naturally Dyed Funky Faroese Socks, K. Benfatto, Elaine 56–61 Su03: 80–83 Book Review. Hooking with Yarn (Taylor). F04: Adam, Mavis Scandinavian-Inspired Mittens and Hat. 18 Button-Up Neck Warmer, K. Su09: 70–71 Su02: 66–72 Book Review. -

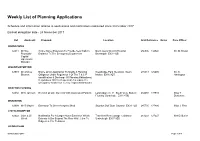

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Weekly List of Planning Applications Schedule and information relating to applications and notifications registered since 30 October 2017 Earliest delegation date - 24 November 2017 Ref Applicant: Proposal: Location Grid Reference Notes Case Officer BARNSTAPLE 64011 Mr Rae Single Storey Extension To Provide New Walk In North Devon District Hospital 256506 134540 Mr. M. Brown Reynolds - Entrance To The Emergency Department Barnstaple EX31 4JB Capital Operations Manager BISHOPS NYMPTON 63973 Mr Andrew Notice Of An Application To Modify A Planning Westbridge Park Newtown South 275843 125605 Mr. S. Blowers Obligation Under Regulation 3 Of The T & C P Molton EX36 3QT Harrington (modification & Discharge Of Planning Obligations) Regulations 1992 In Respect Of Amending The Occupancy Restriction To Key / Agricultural Worker BRATTON FLEMING 64032 Mr K Jackson Erection Of One Dwelling With Associated Parking Land Adjacent 11 South View Bratton 264658 137910 Miss T Fleming Barnstaple EX31 4TQ Blackmore BRAUNTON 63994 Mr R Mayne Extension To Green-keepers Shed Saunton Golf Club Saunton EX33 1LG 245735 137486 Miss J. Pine CHITTLEHAMPTON 64022 John & Jill Notification For A Larger Home Extension Which Travellers Rest Cottage Cobbaton 261233 127227 Mrs D. Butler O'neil Extends 4.00m Beyond The Rear Wall, 3.6m To Umberleigh EX37 9SD Ridge & 2.31m To Eaves GEORGEHAM 06 November 2017 Page 1 of 4 64025 Mr M Notification Of Works To Trees In A Conservation St Georges House Georgeham 246504 139931 42 Days Mr. A. Jones Larrington Area In Respect Of Re-pollarding Of Sycamore Braunton EX33 1JN Notice LB (group A) And Lime (group B), Crown Reduction Of CA Cherry (b), Selective Branch Removal From Sycamore (e) & Recoppicing Of Sycamore (d&e) 64008 Mr & Mrs Erection Of Replacement Dwelling Together With 1 Stoney Cottage Croyde Braunton 243851 139458 Miss S. -

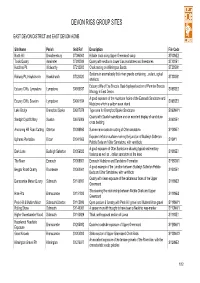

Devon Rigs Group Sites Table

DEVON RIGS GROUP SITES EAST DEVON DISTRICT and EAST DEVON AONB Site Name Parish Grid Ref Description File Code North Hill Broadhembury ST096063 Hillside track along Upper Greensand scarp ST00NE2 Tolcis Quarry Axminster ST280009 Quarry with section in Lower Lias mudstones and limestones ST20SE1 Hutchins Pit Widworthy ST212003 Chalk resting on Wilmington Sands ST20SW1 Sections in anomalously thick river gravels containing eolian ogical Railway Pit, Hawkchurch Hawkchurch ST326020 ST30SW1 artefacts Estuary cliffs of Exe Breccia. Best displayed section of Permian Breccia Estuary Cliffs, Lympstone Lympstone SX988837 SX98SE2 lithology in East Devon. A good exposure of the mudstone facies of the Exmouth Sandstone and Estuary Cliffs, Sowden Lympstone SX991834 SX98SE3 Mudstone which is seldom seen inland Lake Bridge Brampford Speke SX927978 Type area for Brampford Speke Sandstone SX99NW1 Quarry with Dawlish sandstone and an excellent display of sand dune Sandpit Clyst St.Mary Sowton SX975909 SX99SE1 cross bedding Anchoring Hill Road Cutting Otterton SY088860 Sunken-lane roadside cutting of Otter sandstone. SY08NE1 Exposed deflation surface marking the junction of Budleigh Salterton Uphams Plantation Bicton SY041866 SY0W1 Pebble Beds and Otter Sandstone, with ventifacts A good exposure of Otter Sandstone showing typical sedimentary Dark Lane Budleigh Salterton SY056823 SY08SE1 features as well as eolian sandstone at the base The Maer Exmouth SY008801 Exmouth Mudstone and Sandstone Formation SY08SW1 A good example of the junction between Budleigh -

Gwartheg Prydeinig Prin (Ba R) Cattle - Gwartheg

GWARTHEG PRYDEINIG PRIN (BA R) CATTLE - GWARTHEG Aberdeen Angus (Original Population) – Aberdeen Angus (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Belted Galloway – Belted Galloway British White – Gwyn Prydeinig Chillingham – Chillingham Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) – Byrgorn Godro (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol). Galloway (including Black, Red and Dun) – Galloway (gan gynnwys Du, Coch a Llwyd) Gloucester – Gloucester Guernsey - Guernsey Hereford Traditional (Original Population) – Henffordd Traddodiadol (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Highland - Yr Ucheldir Irish Moiled – Moel Iwerddon Lincoln Red – Lincoln Red Lincoln Red (Original Population) – Lincoln Red (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Northern Dairy Shorthorn – Byrgorn Godro Gogledd Lloegr Red Poll – Red Poll Shetland - Shetland Vaynol –Vaynol White Galloway – Galloway Gwyn White Park – Gwartheg Parc Gwyn Whitebred Shorthorn – Byrgorn Gwyn Version 2, February 2020 SHEEP - DEFAID Balwen - Balwen Border Leicester – Border Leicester Boreray - Boreray Cambridge - Cambridge Castlemilk Moorit – Castlemilk Moorit Clun Forest - Fforest Clun Cotswold - Cotswold Derbyshire Gritstone – Derbyshire Gritstone Devon & Cornwall Longwool – Devon & Cornwall Longwool Devon Closewool - Devon Closewool Dorset Down - Dorset Down Dorset Horn - Dorset Horn Greyface Dartmoor - Greyface Dartmoor Hill Radnor – Bryniau Maesyfed Leicester Longwool - Leicester Longwool Lincoln Longwool - Lincoln Longwool Llanwenog - Llanwenog Lonk - Lonk Manx Loaghtan – Loaghtan Ynys Manaw Norfolk Horn - Norfolk Horn North Ronaldsay / Orkney - North Ronaldsay / Orkney Oxford Down - Oxford Down Portland - Portland Shropshire - Shropshire Soay - Soay Version 2, February 2020 Teeswater - Teeswater Wensleydale – Wensleydale White Face Dartmoor – White Face Dartmoor Whitefaced Woodland - Whitefaced Woodland Yn ogystal, mae’r bridiau defaid canlynol yn cael eu hystyried fel rhai wedi’u hynysu’n ddaearyddol. Nid ydynt wedi’u cynnwys yn y rhestr o fridiau prin ond byddwn yn eu hychwanegu os bydd nifer y mamogiaid magu’n cwympo o dan y trothwy. -

Assessing Changes in the Agricultural Productivity of Upland Systems in the Light of Peatland Restoration

Assessing changes in the agricultural productivity of upland systems in the light of peatland restoration Volume 1 of 1 Submitted by Guy William Freeman, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biological Sciences, June 2017. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Thesis abstract Human activity has had a profound negative impact on the structure and function of the earth’s ecosystems. However, with a growing awareness of the value of the services provided by intact ecosystems, restoration of degraded land is increasingly used as a means of reviving ecosystem function. Upland landscapes offer an excellent example of an environment heavily modified by human land use. Agriculture has been the key driver of ecosystem change, but as upland habitats such as peatlands can provide a number of highly valuable services, future change may focus on restoration in order to regain key ecosystem processes. However, as pastoral farming continues to dominate upland areas, ecosystem restoration has the potential to conflict with existing land use. This thesis attempts to assess differences in the agricultural productivity of the different habitat types present in upland pastures. Past and present land use have shaped the distribution of different upland habitat types, and future changes associated with ecosystem restoration are likely to lead to further change in vegetation communities. -

Sheep and Pig Classes Will Be Paid out in Cash on Show Day After 4.00 P.M

40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6_40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6 13/04/2017 11:33 Page 1 www.burwartonshow.co.uk @Burwarton_show BURWARTON SHOW CPH No. 35/023/8000 SatNav: WV16 6RP THURSDAY 3 AUGUST 2017 HEAVYHEAVY HORSEHOR & LIVESTOCK SCHEDULE W NEWNE THREETHRE SHIRES CATTLE TROPHY QUALIFIER ENTRIES CLOSE 4 JULY 2017 The Best in its Field! NEW CLASSES NO DOGS ALLOWED IN THE LIVESTOCK8.15am AREA - 7.00pm 40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6_40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6 13/04/2017 11:33 Page 2 40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6_40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6 13/04/2017 11:33 Page 3 bluefingroup.co.uk BUSINESS FIRST Business and farming insurance solutions and advice that puts your business first. 01584 872 322 ludlow@bluefingroup.co.uk Putting your business first 1 40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6_40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6 13/04/2017 11:33 Page 4 APPLY NOW! WALFORD CAMPUS • Agriculture • Engineering • Outdoor Adventure Levels 2 & 3 Levels 2 & 3 Sport • Animal Management • Equine Levels 2 & 3 Levels 2 & 3 Levels 2 & 3 • Countryside • Foundation Learning Management Entry Level - Level 1 Levels 2 & 3 • Motor Vehicle Levels 1, 2 & 3 Visit the website for full course information at www.nsc.ac.uk WWW.NSC.AC.UK 01939 262 100 2 40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6_40595_LS_Schedule_17_A5_40pp_v6 13/04/2017 11:33 Page 5 Notice to Competitors THIS SCHEDULE IS ISSUED SUBJECT TO THE ORDERS AND REGULATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT FOR ENVIRONMENT, FOOD & RURAL AFFAIRS (DEFRA) – ANIMAL GATHERINGS (INTERIM MEASURES) (ENGLAND) ORDER 2003 (OR AS AMENDED). Entry Fees: The Society is offering concessionary rates in Classes 7 - 196 to exhibitors who are members of the Society. It could well be to your advantage to consider becoming a m ember. Members’ subscription rates and facilities are detailed below SOCIETY MEMBERSHIP Membership is an expression of interest in and support for the aims and objects of the Burwarton & District Agricultural Society and includes the right to attend, take part in and vote at the Annual General Meeting. -

Your Guide to the Very Best Food and Drink in the Local Area Find Out

Your Guide to the very best food and drink in the local area Find out where it comes from and how, where and when to enjoy it. The Taste of Exmoor Bountiful Our Exmoor landscape is bothExmoor breath-taking and bountiful. From top ‘A’ classification oysters straight from the sea at Porlock to Red Ruby Devon cows and Exmoor lambs that graze our nutritious farmland. Deer roam freely across Full Page Advert the high moors and the bees gather pollen from our heather-clad hills. We’ve noticed a growing number of talented Chefs being drawn to the area recently, enticed by the delicious local produce available. We hope you’ll be tempted too. We’ve included some of our favourite places to visit and enjoy good food here. Keep up to date with foodie events and more at www.Visit-Exmoor.co.uk/eatexmoor NORTHMOOR GIN JenVisitnette Exmoor EXMOOR’S PREMIUM QUALITY LOCALLY PRODUCED GIN. FOR A LIST OF LOCAL OUTLETS OR TO ORDER ONLINE VISIT: www.exmoordistillery.co.uk UNIT 5, BARLE ENTERPRISE CENTRE, DULVERTON, EXMOOR, SOMERSET, TA22 9BF PHONE: 01398 323 488 Eat Exmoor Guide Eat Exmoor Guide Copywriting: Jennette Baxter (www.Visit-Exmoor.co.uk) Selected Food Photography: Julia Amies-Green (www.Flymonkeys.co.uk) Design & Production: Tim Baigent (www.glyder.org) With Support from Exmoor National Park Authority. Exmoor’s Landscape –A Farmer’s Perspective Exmoor’s unspoilt landscape is of livestock, hence the characteristic a major reason why it became a patchworks of grassy fields bounded national park, but even its ancient by high hedges. -

North Devon AONB RIGS

REPORT ON THE ASSESSMENT OF COUNTY GEOLOGICAL SITES IN THE NORTH DEVON AREAS OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY Phase 2 Area from Saunton - Morte Point – Ifracombe and Ilfracombe – Combe Martin REPORT ON THE ASSESSMENT OF COUNTY GEOLOGICAL SITES IN THE NORTH DEVON AREAS OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY Phase 2 Area from Saunton - Morte Point – Ifracombe and Ilfracombe – Combe Martin E.C. FRESHNEY and J.A. BENNETT Prepared by: Devon RIGS Group February, 2006 For: Northern Devon Coast and Countryside Service CONTENTS Introduction 1 Summary of the geology of the North Devon AONB and its immediate surroundings 6 Appendix 1 Description of sites Appendix 2 Glossary FIGURES Figure 1 Map showing area of northern part of North Devon AONB with positions of SSSIs, GCRs and proposed County Geological Sites 3 Figure 2 Geological map of the northern part of the North Devon AONB 7 Figure 3 Stratigraphy of the northern part of the North Devon AONB 8 Figure 4 Generalised relationship of cleavage to bedding in the North Devon area showing possible thrust fault at depth. 12 TABLES Table 1 Geological SSSIs and GCRs in North Devon AONB 3-4 Table 2. Proposed County Geological Sites 5 PLATES (All in Appendix 1) Plate 1 Purple sandstones and greenish grey slates and siltstones of Pickwell Down Sandstones. Plate 2 Purple sandstone in Pickwell Down Sandstones showing more massive lower part to right overlain by more muddy laminated upper part where the cleavage is more marked ..Plate 3. Top part of sandstone seen in Figure 2 showing cross-bedding and cleavage. Plate 4 Sandstone showing small scale cross-lamination (ripple drift bedding) Plate 5 Purple sandstones with greenish grey siltstones and a mud clast conglomerate.