Creators and Guardians of Breeds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

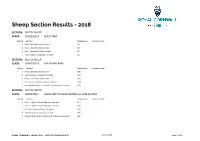

Sheep Section Results - 2018

Sheep Section Results - 2018 SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0312 AGED RAM Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (3) 2 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (4) 3 Miss T Cobbledick, Bude, Cornwall (2) 7 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (5) SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0313 SHEARLING RAM Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (10) 2 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (12) 3 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (11) 4 Mr S & Mrs G Renfree, Liskeard, Cornwall (20) 7 Mrs M A Heard & Mr G J Garland, Wiveliscombe, Somerset (15) SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0314 AGED EWE TO HAVE REARED A LAMB IN 2018 Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Miss A H & Mrs S Payne, Newquay, Cornwall (27) 2 Miss A H & Mrs S Payne, Newquay, Cornwall (28) 3 Miss J M Lapthorne, Plymouth, Devon (26) 4 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (23) 7 Mrs M A Heard & Mr G J Garland, Wiveliscombe, Somerset (24) ROYAL CORNWALL SHOW 2018 - SHEEP SECTION RESULTS 13 June 2018 Page 1 of 64 SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0315 SHEARLING EWE Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mr H Williams, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire (49) 2 Mrs M A Heard & Mr G J Garland, Wiveliscombe, Somerset (38) 3 Mr S & Mrs G Renfree, Liskeard, Cornwall (47) 4 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (34) 5 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (36) 6 Mr S & Mrs G Renfree, Liskeard, Cornwall (48) 7 Mr H Williams, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire (50) SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0316 RAM LAMB Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. -

Gwartheg Prydeinig Prin (Ba R) Cattle - Gwartheg

GWARTHEG PRYDEINIG PRIN (BA R) CATTLE - GWARTHEG Aberdeen Angus (Original Population) – Aberdeen Angus (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Belted Galloway – Belted Galloway British White – Gwyn Prydeinig Chillingham – Chillingham Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) – Byrgorn Godro (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol). Galloway (including Black, Red and Dun) – Galloway (gan gynnwys Du, Coch a Llwyd) Gloucester – Gloucester Guernsey - Guernsey Hereford Traditional (Original Population) – Henffordd Traddodiadol (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Highland - Yr Ucheldir Irish Moiled – Moel Iwerddon Lincoln Red – Lincoln Red Lincoln Red (Original Population) – Lincoln Red (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Northern Dairy Shorthorn – Byrgorn Godro Gogledd Lloegr Red Poll – Red Poll Shetland - Shetland Vaynol –Vaynol White Galloway – Galloway Gwyn White Park – Gwartheg Parc Gwyn Whitebred Shorthorn – Byrgorn Gwyn Version 2, February 2020 SHEEP - DEFAID Balwen - Balwen Border Leicester – Border Leicester Boreray - Boreray Cambridge - Cambridge Castlemilk Moorit – Castlemilk Moorit Clun Forest - Fforest Clun Cotswold - Cotswold Derbyshire Gritstone – Derbyshire Gritstone Devon & Cornwall Longwool – Devon & Cornwall Longwool Devon Closewool - Devon Closewool Dorset Down - Dorset Down Dorset Horn - Dorset Horn Greyface Dartmoor - Greyface Dartmoor Hill Radnor – Bryniau Maesyfed Leicester Longwool - Leicester Longwool Lincoln Longwool - Lincoln Longwool Llanwenog - Llanwenog Lonk - Lonk Manx Loaghtan – Loaghtan Ynys Manaw Norfolk Horn - Norfolk Horn North Ronaldsay / Orkney - North Ronaldsay / Orkney Oxford Down - Oxford Down Portland - Portland Shropshire - Shropshire Soay - Soay Version 2, February 2020 Teeswater - Teeswater Wensleydale – Wensleydale White Face Dartmoor – White Face Dartmoor Whitefaced Woodland - Whitefaced Woodland Yn ogystal, mae’r bridiau defaid canlynol yn cael eu hystyried fel rhai wedi’u hynysu’n ddaearyddol. Nid ydynt wedi’u cynnwys yn y rhestr o fridiau prin ond byddwn yn eu hychwanegu os bydd nifer y mamogiaid magu’n cwympo o dan y trothwy. -

Assessing Changes in the Agricultural Productivity of Upland Systems in the Light of Peatland Restoration

Assessing changes in the agricultural productivity of upland systems in the light of peatland restoration Volume 1 of 1 Submitted by Guy William Freeman, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biological Sciences, June 2017. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Thesis abstract Human activity has had a profound negative impact on the structure and function of the earth’s ecosystems. However, with a growing awareness of the value of the services provided by intact ecosystems, restoration of degraded land is increasingly used as a means of reviving ecosystem function. Upland landscapes offer an excellent example of an environment heavily modified by human land use. Agriculture has been the key driver of ecosystem change, but as upland habitats such as peatlands can provide a number of highly valuable services, future change may focus on restoration in order to regain key ecosystem processes. However, as pastoral farming continues to dominate upland areas, ecosystem restoration has the potential to conflict with existing land use. This thesis attempts to assess differences in the agricultural productivity of the different habitat types present in upland pastures. Past and present land use have shaped the distribution of different upland habitat types, and future changes associated with ecosystem restoration are likely to lead to further change in vegetation communities. -

Your Guide to the Very Best Food and Drink in the Local Area Find Out

Your Guide to the very best food and drink in the local area Find out where it comes from and how, where and when to enjoy it. The Taste of Exmoor Bountiful Our Exmoor landscape is bothExmoor breath-taking and bountiful. From top ‘A’ classification oysters straight from the sea at Porlock to Red Ruby Devon cows and Exmoor lambs that graze our nutritious farmland. Deer roam freely across Full Page Advert the high moors and the bees gather pollen from our heather-clad hills. We’ve noticed a growing number of talented Chefs being drawn to the area recently, enticed by the delicious local produce available. We hope you’ll be tempted too. We’ve included some of our favourite places to visit and enjoy good food here. Keep up to date with foodie events and more at www.Visit-Exmoor.co.uk/eatexmoor NORTHMOOR GIN JenVisitnette Exmoor EXMOOR’S PREMIUM QUALITY LOCALLY PRODUCED GIN. FOR A LIST OF LOCAL OUTLETS OR TO ORDER ONLINE VISIT: www.exmoordistillery.co.uk UNIT 5, BARLE ENTERPRISE CENTRE, DULVERTON, EXMOOR, SOMERSET, TA22 9BF PHONE: 01398 323 488 Eat Exmoor Guide Eat Exmoor Guide Copywriting: Jennette Baxter (www.Visit-Exmoor.co.uk) Selected Food Photography: Julia Amies-Green (www.Flymonkeys.co.uk) Design & Production: Tim Baigent (www.glyder.org) With Support from Exmoor National Park Authority. Exmoor’s Landscape –A Farmer’s Perspective Exmoor’s unspoilt landscape is of livestock, hence the characteristic a major reason why it became a patchworks of grassy fields bounded national park, but even its ancient by high hedges. -

SOME ECONOMIC ASPECTS of the SHEEP INDUSTRY in the WEST of ENGLAND Report No

LNjNI FOUNpATION OF ACZ1ICULTURAL E66PO.L1103 LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF BRISTOL DEPARTMENT of ECONOMICS (Agricultural Economics). SOME ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF THE SHEEP INDUSTRY IN THE WEST OF ENGLAND Report No. 1 Store Lamb Production in the Upland Areas of S.W. Somerset by R. R. JEFFERY Price 5s. .. i . SOME ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF THE SHEEP INDUSTRY IN THE WEST OF ENGLAND Report No. 1 Store Lamb Production in the Upland Areas of S.W. Somerset General THE changes brought about in the structure of British agri- culture, and especially in the relative importance of the various agricultural products by the exigencies of wartime and post- war conditions have been very great indeed. Nowhere has the change been more striking than in the case of mutton and lamb production which fell from a pre-war (1937-39) average of 214,000 tons to 117,000 tons in 1947, and has since recovered to approximately 149,000 tons in 1950. TABLE I Annual Production of Mutton and Lanb and of Beef in the United Kingdom Average 1937-8-9 to 1949 Mutton and Lamb Beef Tons Tons (000) % (000) % 1937-39 Average 214 100-0 591 100-0 1940 . 227 106-1 557 94-2 1941 . 176 82-2 523 88-5 1942 . 171 79-9 453 76-6 1943 . 159 74-3 445 75-3 1944 . 442 66-4 487 824 1945 . 134 62-6 517 87-5 1946 . 152 71-0 538 91-0 1947 . 117 54-7 479 81-0 1948 . 123 57-5 470 79-5 1949 . 140 654 502 84-9 1950* 149 69-6 605 1024 * Approximate figures. -

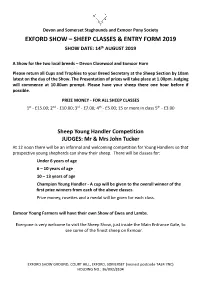

Sheep Classes & Entry Form 2019

Devon and Somerset Staghounds and Exmoor Pony Society EXFORD SHOW – SHEEP CLASSES & ENTRY FORM 2019 SHOW DATE: 14th AUGUST 2019 A Show for the two local breeds – Devon Closewool and Exmoor Horn Please return all Cups and Trophies to your Breed Secretary at the Sheep Section by 10am latest on the day of the Show. The Presentation of prizes will take place at 1.00pm. Judging will commence at 10.00am prompt. Please have your sheep there one hour before if possible. PRIZE MONEY - FOR ALL SHEEP CLASSES 1st - £15.00; 2nd - £10.00; 3rd - £7.00; 4th - £5.00; 15 or more in class 5th - £3.00 Sheep Young Handler Competition JUDGES: Mr & Mrs John Tucker At 12 noon there will be an informal and welcoming competition for Young Handlers so that prospective young shepherds can show their sheep. There will be classes for: Under 6 years of age 6 – 10 years of age 10 – 13 years of age Champion Young Handler - A cup will be given to the overall winner of the first prize winners from each of the above classes. Prize money, rosettes and a medal will be given for each class. Exmoor Young Farmers will have their own Show of Ewes and Lambs. Everyone is very welcome to visit the Sheep Show, just inside the Main Entrance Gate, to see some of the finest sheep on Exmoor. EXFORD SHOW GROUND, COURT HILL, EXFORD, SOMERSET (nearest postcode TA24 7NC) HOLDING NO.: 36/092/8104 Devon and Somerset Staghounds and Exmoor Pony Society EXMOOR HORN JUDGE: Mr Edward Harding Breed Secretary: Mrs Jan Brown All classes confined to sheep registered in their respective Flock Book. -

ENRR069 Part 1

ENGLISH NATURE Review of the impact of extensive livestock farming systems on nature consevration and the environment Phase 2 - Final report: No. 69 - English Nature Research Reports working today for nature tomorrow English Nature Research Reports Prepared for English Nature by CEAS Consultants (Wye) Ltd and Wye Gollcge (University of London) Further copies of this report can be obtained from Rural Land Use Branch, Policy Directorate, English Nature, Northminster Rouse, Peterborough PE1 1UA ISSN 0967-876X 0 English Nature 1993 I I Report for English Nature CEAS Consultants (Wye) Ltd Centre for European Agricultural Studies in collaboration with Wye College (University of London) Telephone: 0233 81 21 81 Fax: 0233 813309 Telex: 849228 PRQMAR G CEAS 1400/NW February 1993 Contents 1lNTRODUCTlON ........................................... 1 .I The English Nature study of livestock extensification .............. 1.2 The MAFF pilot schemes ................................. 1.3 Objectives of the pilot schemes ............................. 1.4 The coverage and nature of the pilot schemes ................... 1.4.1 Rules that apply to other products on the participant’s holdings throughout the duration of the schemes .................... 4 I .4.2 Rules on the maintenance of the environment ............... 4 1.4.3 Rules which the farmer must follow when reducing his ewe numbers .......................................... 5 1.5 Effectiveness of the pilot schemes ........................... 5 2 SUMMARY OF PROPOSED EXTENSlFlCATlON PRESCRIPTIONS .......... 7 2.1 Reduce stocking rates ................................... 7 2.2.1 Flat rate stocking densities ............................ 7 2.1.2 Stocking rate adjusted to sward composition ............... 8 2.2 Reduced fertiliser application alongside lower stocking rates ......... 9 2. 3 Switch from silage to hay ................................ 10 2.3.1 Hay .......................................... -

Marketing Pack

Marketing Pack Congratulations! You’ve decided to start marketing and selling your own yarn. This pack will give you some ideas and tips about branding, marketing and selling direct to customers. Start by asking yourself these three questions, which this pack will ad- dress in turn: What’s special about your wool? What exactly are you selling? Who is your customer, how will they buy it & how much should you charge? What’s special about British wool? You can be evangelical about this gorgeous product and its benefits for health, for the economy, and for the environment. British wool is a unique product and you can sing its praises from the rooftops. Fire retardant 100% natural product Can be organically certified UV protective Wool uses less energy Renewable & than man-made fi- sustainable bres during manu- facture Easy care Odour resistant Biodegradable Natural insulator Resilient and elastic Breathable Hypoallergenic, traps dust (from the Campaign for Wool website) What’s special about your wool? Capture your passion for farming and the gorgeous product that you are cre- ating. What’s exciting about your farm, your story and your product that will set you apart from other yarns on the market? Think about how to describe what you’re selling in ways which will attract buy- ers. Who you are, information about your farm and animals, breeds, and your reasons for making yarn. People buy things they want or need, but also make their choices based on emotional connections with the products, such as brand identity, locality, values and environmental considerations, availability, repeata- bility, reliability, and, of course, price. -

Lowland Sheep Production Policies and Practices

Agricu:tural Enterprise Studies in England and Wales Economic Report No.1 LOWLAND SHEEP PRODUCTION POLICIES AND PRACTICES Lowland Sheep Study Group Editor: W.J.K.Thomas Published by the University of Exeter October 1970 Price 50p (10s.) AN INTRODUCTION TO "AGRICULTURAL ENTERPRISE STUDIES IN ENGLAND AND WALES" University departments of agricultural economics in England and Wales, which formed the Provincial Agricultural Economics Service, have for many years conducted economic studies of farm and horticultural enterprises. Such studies are now being undertaken as a co-ordinated programme of investigations commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. The reports of these studies will be published in a new national series entitled "Agricultural Enterprise Studies in England and Wales" of which the present report is the first. The studies are designed to assist farmers, growers, advisors, and administrators by investigating problems and obtaining economic data to help in decision making and planning. It is hoped that • they will also be useful in teaching and research. The responsibia7 for formulating the programme of studies rests with the Enterprise Studies Sub-Committee, on which the Universities, the Ministry (including the National Agricultural Advisory Service) are represented. Copies of the reports may be obtained from the University departments concerned, whose addresses are given at the end of this report. 1ME LOWLAND SHEEP STUDY GFOUP Agricultural Economics Unit University of Exeter (the co-ordinating Unit) • Agricultural Economics Research Unit University of Bristol Farm Management Unit University of Nottingham School of Rural Economics and Related Studies Wye College (University of London) • Meat and Livestock Comnission Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (including the National Agricultural Advisory Service) This report is published by the University of Exeter and is available from: Agricultural Economics Unit University of Exeter Lafrowda • St. -

Breed-Book.Pdf

British Shee p A guide to British sheep breeds and their unique wool wool lana wolle laine wol lãW uElLdCO uMllE 羊TO毛 lla suf yün vlna vuna lesOhU aRl Bí RgIyTaISpHj úSH vEiElPna wełna lân volna len wool lan&a WwOoOlLl eB OlaOiK ne l lã uld uăll villa suf yün vlna vuna lesh alí apjú vilna wełna lân volna len wool lana wolle laine wol lã uldă ull villa suf yün vlna una lesh alí gyapjú vilna wełna lân volna n wool lana wolle laine wol lã uld uăll villa suf yün vlna vuna lesh alí gyapjú ilna wełшnaе lрâсn ть volna len wool lana wolle laine wol lã uldă ull 羊毛 villa suf yün vlna vuna ขน lesh alí gyapjú vilna wełna lân volna len wool lana wolle laine wol lã ulăd wol ull 羊毛 villa suf yün vlna vuna lesh alí apjú vilna wełna lân volna len wool lana wolle laine wol ă lã uld ull villa suf yün vlna vuna lesμhα aλlλí ίgyapjú vilna wełna ân volna len wool lana wolle laine wol lã ă FOREWORD The sheep population of Britain is constantly evolving, thanks to both changing farming patterns and developments within the many breeds of sheep kept here. In the third edition of this very popular book, the Wool Board has tried to portray an accurate picture of the types of sheep kept at the beginning of the 21 st century. Considerable assistance has been given by many breed societies in the production of this publication, for which the Wool Board is very grateful. -

Sheep Identification Sheet

Sheep identification sheet Beltex The breed is an offshoot of the Texel breed from Belgium, giving the name BELTEX. It is a white faced sheep with medium-length wool. It is best known for its large mus- cles, especially in the hindquarters Black Welsh Mountain The Black Welsh Mountain is a small, black sheep with no wool on the face or on the legs below the knee and hock. The rams are usually horned and the females are polled (hornless). Sheep identification sheet Bleu Du Maine The Bleu Du Maine Sheep is a breed of domestic sheep that originated in western France. The most distinctive charac- teristic of the breed is its bald, grey–blue head which is polled in both sexes. Though this breed does grow wool, it is raised primarily for meat. The Bluefaced Leicester is a longwool breed of sheep which originates Bluefaced from Northumberland. This breed is raised primarily for meat, but their Leicester fleece is becoming increasingly popular forhand spinning. They have curly threadlike wool which makes it considerably lighter than others. Bluefaced Leicester's are recognisable through their Roman noses, which have a dark blue skin which can be seen through the white hair. Border Leicester The Border Leicester is a breed of sheep originating in England and raised primarily for meat. Border Leicester's are polled (without horns), long woollen sheep. Though large in size and robust, they are also docile. Sheep identification sheet Charollais The Charollais is a medium to large sized sheep, long and well muscled with thick, deep gigots (legs). -

British Sheep Breeds As a Part of World Sheep Gene Pool Landscape: Looking Into Genomic Applications

animals Review British Sheep Breeds as a Part of World Sheep Gene Pool Landscape: Looking into Genomic Applications Michael N. Romanov 1,* , Natalia A. Zinovieva 2 and Darren K. Griffin 1 1 School of Biosciences, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7NJ, UK; D.K.Griffi[email protected] 2 L.K. Ernst Federal Research Center for Animal Husbandry, Dubrovitsy Estate, Podolsk District, Moscow Region, 142132 Podolsk, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The UK can be proud of the fact that numerous native breeds of sheep have been developed here that possess unique phenotypic features and excellent productivity and are utilized throughout the world. Their remarkable popularity and further sustainable breeding on grass pastures of British Isles and elsewhere can benefit from genomic applications. Abstract: Sheep farming has been an important sector of the UK’s economy and rural life for many centuries. It is the favored source of wool, meat and milk products. In the era of exponential progress in genomic technologies, we can now address the questions of what is special about UK sheep breed genotypes and how they differ genetically form one another and from other countries. We can reflect how their natural history has been determined at the level of their genetic code and what traces have been left in their genomes because of selection for phenotypic traits. These include adaptability to certain environmental conditions and management, as well as resistance to disease. Application of Citation: Romanov, M.N.; Zinovieva, these advancements in genetics and genomics to study sheep breeds of British domestic selection has N.A.; Griffin, D.K.