Technical Appendix to the Above Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agricultural Survey

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) DOCUMENTS PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF MAINE. 1861. AUGUSTA: j STEVENS & SAYWARD, PRINTERS TO THE STATE. 18 61. TELEGRAPH. ·BLACK HAWK STALLION, OWNED BY THOS,S.LANG,£S.P. NORlH VASSALBORO. FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE SECRETARY OF THE MAINE BOARD OF AGRICULTURE. 1860. AUGUSTA: STEVENS & SAYWARD, PRINTERS TO THE STATE. 18 6 0. BOARD OF AGRICULTURE .... 1860. ISAAC REED, President. JOHN F. ANDERSON, Vice Presulent. S. L. GOODALE, Secretary. NAME. SOCIETY. P. O. ADDRESS. Term expires January, 1861. John F. Anderson, Cumberland, South Windham. George A. Rogers, Sagadahoc, Topsham. W. E. Drummond, North Kennebec, Winslow. S. L. Goodale, York, Saco. Daniel Lancaster, South Kennebec, Farmingdale. Wm. M. Palmer, East Somerset, Hartland. E. B. Stackpole, West Penobscot, Kenduskeag. N. T. True, Oxford, Bethel. Term expires January, 1862. Seward Dill, North Franklin, • Phillips. E. L. Hammond, Piscataquis, Atkinson. Ashur Davis, North Somerset, South Solon. Hugh Porter, Washington, Pembroke. J. S. Chandler, Franklin, New Sharon. Joel Bean, North Aroostook, Presque Isle. Wm. C. Hammatt, North Penobscot, Howland. Albert Noyes, Bangor Horticultural, Bangor. Alfred Cushman, Penob. & Aroostook Union, Golden Ridge. Samuel Wasson, Hancock, Franklin. Term expires January, 1863. Isaac Reed, Lincoln, Waldoboro'. Albert Moore, West Somerset, North Anson. David Cargill, Kennebec, East Winthrop. Robert Martin, Audrosco ggin, "\Vest Danville. Calvin Chamberlain, Maine State, Fox croft. -

Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019

Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019 First published July 2021 Natural England Research Report NERR099 www.gov.uk/natural-england Nettlecombe NVC Final Report Natural England Research Report NERR099 Natural England Research Report NERR099 Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019 A.McLay July 2021 This report is published by Natural England under the Open Government Licence - OGLv3.0 for public sector information. You are encouraged to use, and reuse, information subject to certain conditions. For details of the licence visit Copyright. Natural England photographs are only available for non-commercial purposes. If any other information such as maps or data cannot be used commercially this will be made clear within the report. ISBN: 978-1-78354-770-8 © Natural England 2021 Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019 Natural England Research Report NERR099 Project details This report should be cited as: McLay, A. 2021. Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019 Natural England Research Report NERR099. Natural England. Natural England Project manager Mike Pearce Author A.McLay Keywords Nettlecombe Park, grassland survey, grassland fungi, SSSI Further information This report can be downloaded from the Natural England Access to Evidence Catalogue: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/ . For information on Natural England publications -

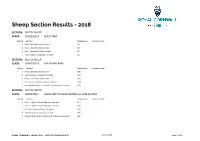

Sheep Section Results - 2018

Sheep Section Results - 2018 SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0312 AGED RAM Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (3) 2 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (4) 3 Miss T Cobbledick, Bude, Cornwall (2) 7 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (5) SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0313 SHEARLING RAM Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (10) 2 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (12) 3 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (11) 4 Mr S & Mrs G Renfree, Liskeard, Cornwall (20) 7 Mrs M A Heard & Mr G J Garland, Wiveliscombe, Somerset (15) SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0314 AGED EWE TO HAVE REARED A LAMB IN 2018 Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Miss A H & Mrs S Payne, Newquay, Cornwall (27) 2 Miss A H & Mrs S Payne, Newquay, Cornwall (28) 3 Miss J M Lapthorne, Plymouth, Devon (26) 4 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (23) 7 Mrs M A Heard & Mr G J Garland, Wiveliscombe, Somerset (24) ROYAL CORNWALL SHOW 2018 - SHEEP SECTION RESULTS 13 June 2018 Page 1 of 64 SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0315 SHEARLING EWE Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mr H Williams, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire (49) 2 Mrs M A Heard & Mr G J Garland, Wiveliscombe, Somerset (38) 3 Mr S & Mrs G Renfree, Liskeard, Cornwall (47) 4 Mrs C L Elworthy, Exeter, Devon (34) 5 L & V Gregory, Launceston, Cornwall (36) 6 Mr S & Mrs G Renfree, Liskeard, Cornwall (48) 7 Mr H Williams, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire (50) SECTION: BELTEX SHEEP CLASS: S0001/0316 RAM LAMB Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. -

The Blackmore Country (1906)

I II i II I THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES IN THE SAME SERIES PRICE 6/- EACH THE SCOTT COUNTRY THE BURNS COUNTRY BY W. S. CROCKETT BY C. S. DOOGALL Minister of Twccdsmuir THE THE THACKERAY COUNTRY CANTERBURY PILGRIMAGES BY LEWIS MELVILLE BY II. SNOWDEN WARD THE INQOLDSBY COUNTRY THE HARDY COUNTRY BY CHAS. G. HAKI'ER BY CHAS. G. HARPER PUBLISHED BY ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK, SOHO SQUARE, LONDON Zbc pWQVimnQC Series CO THE BLACKMORE COUNTRY s^- Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/blackmorecountryOOsneliala ON THE LYN, BELOW BRENDON. THE BLACKMORE COUNTRY BY F. J. SNELL AUTHOR OF 'A BOOK OF exmoob"; " kably associations of archbishop temple," etc. EDITOR of " UEMORIALS OF OLD DEVONSHIRE " WITH FIFTY FULL -PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY C. W. BARNES WARD LONDON ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1906 " So holy and so perfect is my love, That I shall think it a most plenteous crop To glean the broken ears after the man That the main harvest reaps." —Sir Phiup SroNEY. CORRIGENDA Page 22, line 20, for " immorality " read " morality." „ 128, „ 2 1, /or "John" r^a^/" Jan." „ 131, „ 21, /<7r "check" r?a^ "cheque." ; PROLOGUE The " Blackmore Country " is an expression requiring some amount of definition, as it clearly will not do to make it embrace the whole of the territory which he annexed, from time to time, in his various works of fiction, nor even every part of Devon in which he has laid the scenes of a romance. -

January-February 2021

Page 1 Issue No. 127 Village News January - February 2021 Monkton Heathfield, West Monkton and Bathpool Getting Up-Close and Personal with a Wooly Mamoth See Page 8 Contents: Useful Numbers/Regular Bookings - Page 2 Somerset Birds - Page 3 Broomsquires - Page 4 & 5 South Quantock Benefice - Page 6 Bishop Peter/Bathpool Chapel/100 Club - Page 7 School News - Page 8 Oak Partnership/Gardening Corner - Page 9 Find out more about Carrion Crows Parish Council - Pages 10 & 11 See Page 3 WI Walks - Page 12 Sports Pitches - Page 13 Happy New Year Memories of Hestercombe - Page 14 from Hestercombe Cont/Village Hall - Page 15 all of us at the Village News WM&CF Film Club/Blood Donations/Debt Help/Walking Football - Page 16 Taunton Scrubbers/And Finally - Page 24 Publication in the Village News does not imply an endorsement. The Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions. The information contained within this publication is published in good faith. Volunteers deliver this publication to homes in West Monkton, Monkton Heathfield, Bathpool, Gotton and Goosenford. Copy deadline for March - April 2021 is 1st February 2021 Page 2 Useful Names and Telephone Numbers Regular Events at West Monkton Village Hall Monkton Heathfield, TA2 8NE Rector: Rev. Mary Styles - 01823 451189 The Vicarage, Kingston St Mary, TA2 8HW Slimming World Associate Vicar half-time: Rev Jim Cox - 01823 333377 Mondays 09:00 - 11:00 Churchwarden: Hazel Adams - 01823 443027 Phoenix Camera Club P.C.C Secretary: Samm Barge - 07976415337 Mondays 19:00 - 22:00 P.C.C -

Gwartheg Prydeinig Prin (Ba R) Cattle - Gwartheg

GWARTHEG PRYDEINIG PRIN (BA R) CATTLE - GWARTHEG Aberdeen Angus (Original Population) – Aberdeen Angus (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Belted Galloway – Belted Galloway British White – Gwyn Prydeinig Chillingham – Chillingham Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) – Byrgorn Godro (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol). Galloway (including Black, Red and Dun) – Galloway (gan gynnwys Du, Coch a Llwyd) Gloucester – Gloucester Guernsey - Guernsey Hereford Traditional (Original Population) – Henffordd Traddodiadol (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Highland - Yr Ucheldir Irish Moiled – Moel Iwerddon Lincoln Red – Lincoln Red Lincoln Red (Original Population) – Lincoln Red (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Northern Dairy Shorthorn – Byrgorn Godro Gogledd Lloegr Red Poll – Red Poll Shetland - Shetland Vaynol –Vaynol White Galloway – Galloway Gwyn White Park – Gwartheg Parc Gwyn Whitebred Shorthorn – Byrgorn Gwyn Version 2, February 2020 SHEEP - DEFAID Balwen - Balwen Border Leicester – Border Leicester Boreray - Boreray Cambridge - Cambridge Castlemilk Moorit – Castlemilk Moorit Clun Forest - Fforest Clun Cotswold - Cotswold Derbyshire Gritstone – Derbyshire Gritstone Devon & Cornwall Longwool – Devon & Cornwall Longwool Devon Closewool - Devon Closewool Dorset Down - Dorset Down Dorset Horn - Dorset Horn Greyface Dartmoor - Greyface Dartmoor Hill Radnor – Bryniau Maesyfed Leicester Longwool - Leicester Longwool Lincoln Longwool - Lincoln Longwool Llanwenog - Llanwenog Lonk - Lonk Manx Loaghtan – Loaghtan Ynys Manaw Norfolk Horn - Norfolk Horn North Ronaldsay / Orkney - North Ronaldsay / Orkney Oxford Down - Oxford Down Portland - Portland Shropshire - Shropshire Soay - Soay Version 2, February 2020 Teeswater - Teeswater Wensleydale – Wensleydale White Face Dartmoor – White Face Dartmoor Whitefaced Woodland - Whitefaced Woodland Yn ogystal, mae’r bridiau defaid canlynol yn cael eu hystyried fel rhai wedi’u hynysu’n ddaearyddol. Nid ydynt wedi’u cynnwys yn y rhestr o fridiau prin ond byddwn yn eu hychwanegu os bydd nifer y mamogiaid magu’n cwympo o dan y trothwy. -

Assessing Changes in the Agricultural Productivity of Upland Systems in the Light of Peatland Restoration

Assessing changes in the agricultural productivity of upland systems in the light of peatland restoration Volume 1 of 1 Submitted by Guy William Freeman, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biological Sciences, June 2017. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Thesis abstract Human activity has had a profound negative impact on the structure and function of the earth’s ecosystems. However, with a growing awareness of the value of the services provided by intact ecosystems, restoration of degraded land is increasingly used as a means of reviving ecosystem function. Upland landscapes offer an excellent example of an environment heavily modified by human land use. Agriculture has been the key driver of ecosystem change, but as upland habitats such as peatlands can provide a number of highly valuable services, future change may focus on restoration in order to regain key ecosystem processes. However, as pastoral farming continues to dominate upland areas, ecosystem restoration has the potential to conflict with existing land use. This thesis attempts to assess differences in the agricultural productivity of the different habitat types present in upland pastures. Past and present land use have shaped the distribution of different upland habitat types, and future changes associated with ecosystem restoration are likely to lead to further change in vegetation communities. -

Habitats Regulations Assessment for the Preferred Strategy

THE WEST SOMERSET LOCAL PLAN 2012 TO 2032 DRAFT PREFERRED STRATEGY HABITAT REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT January 2012 This report was prepared by Somerset County Council on behalf of the Exmoor National Park Authority, as the 'competent authority' under the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010. Copyright The maps in this report are reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. (Somerset County Council)(100038382)(2011) 2 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4 2. Screening Exercise ..................................................................................................... 6 3. Characteristics and Description of the Natura 2000 Sites ........................................... 8 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 8 Identification of Natura 2000 sites................................................................................ 8 Ecological Zones of Influence .................................................................................... 11 Description and Characterisation of Natura 2000 Sites ............................................. 11 4. Potential Impacts of the Plan on Ecology ................................................................. -

Published by ENPA November 2009 1 EXMOOR NATIONAL PARK

EXMOOR NATIONAL PARK EMPLOYMENT LAND REVIEW Published by ENPA November 2009 1 Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd 1st Floor, Westville House Fitzalan Court Cardiff CF24 0EL Offices also in T 029 2043 5880 London F 029 2049 4081 Manchester Newcastle upon Tyne [email protected] www.nlpplanning.com Contents2 Executive Summary 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION 11 Scope of the Study 11 The Implications of Exmoor’s Status as a National Park 13 Methodology 15 Report Structure 18 2.0 Local Context 19 Geographical Context 19 Population 21 Economic Activity 22 Distribution of Employees by Sector 25 Qualifications 28 Deprivation 29 Commuting Patterns 32 Businesses 36 Conclusion 36 3.0 Policy Context 37 Planning Policy Context 37 Economic Policy Context 42 Conclusion 48 4.0 The Current Stock of Employment Space 50 Existing Stock of Employment Floorspace 50 Existing Employment Land Provision 55 Conclusion 61 5.0 Consultation 63 Agent Interviews 63 Stakeholder Consultation 65 Business Consultation 68 Previous Consultation Exercises 73 Conclusion 80 6.0 Qualitative Assessment of Existing Employment Sites 81 Conclusion 90 7.0 The Future Economy of Exmoor National Park 92 Establishing an Economic Strategy 92 Influences upon the Economy 93 Key Sectors 95 1 30562/517407v2 Conclusion 97 8.0 Future Need for Employment Space 99 Employment Growth 99 Employment Based Space Requirements 105 Planning Requirement for Employment Land 112 9.0 The Role of Non-B Class Sectors in the Local Economy 114 Introduction 114 Agriculture 114 Public Sector Services 119 Retail 122 10.0 -

North and Mid Somerset CFMP

` Parrett Catchment Flood Management Plan Consultation Draft (v5) (March 2008) We are the Environment Agency. It’s our job to look after your environment and make it a better place – for you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Working with business, Government and society as a whole, we are making your environment cleaner and healthier. The Environment Agency. Out there, making your environment a better place. Published by: Environment Agency Rio House Waterside Drive, Aztec West Almondsbury, Bristol BS32 4UD Tel: 01454 624400 Fax: 01454 624409 © Environment Agency March 2008 All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Environment Agency Parrett Catchment Flood Management Plan – Consultation Draft (Mar 2008) Document issue history ISSUE BOX Issue date Version Status Revisions Originated Checked Approved Issued to by by by 15 Nov 07 1 Draft JM/JK/JT JM KT/RR 13 Dec 07 2 Draft v2 Response to JM/JK/JT JM/KT KT/RR Regional QRP 4 Feb 08 3 Draft v3 Action Plan JM/JK/JT JM KT/RR & Other Revisions 12 Feb 08 4 Draft v4 Minor JM JM KT/RR Revisions 20 Mar 08 5 Draft v5 Minor JM/JK/JT JM/KT Public consultation Revisions Consultation Contact details The Parrett CFMP will be reviewed within the next 5 to 6 years. Any comments collated during this period will be considered at the time of review. Any comments should be addressed to: Ken Tatem Regional strategic and Development Planning Environment Agency Rivers House East Quay Bridgwater Somerset TA6 4YS or send an email to: [email protected] Environment Agency Parrett Catchment Flood Management Plan – Consultation Draft (Mar 2008) Foreword Parrett DRAFT Catchment Flood Management Plan I am pleased to introduce the draft Parrett Catchment Flood Management Plan (CFMP). -

Your Guide to the Very Best Food and Drink in the Local Area Find Out

Your Guide to the very best food and drink in the local area Find out where it comes from and how, where and when to enjoy it. The Taste of Exmoor Bountiful Our Exmoor landscape is bothExmoor breath-taking and bountiful. From top ‘A’ classification oysters straight from the sea at Porlock to Red Ruby Devon cows and Exmoor lambs that graze our nutritious farmland. Deer roam freely across Full Page Advert the high moors and the bees gather pollen from our heather-clad hills. We’ve noticed a growing number of talented Chefs being drawn to the area recently, enticed by the delicious local produce available. We hope you’ll be tempted too. We’ve included some of our favourite places to visit and enjoy good food here. Keep up to date with foodie events and more at www.Visit-Exmoor.co.uk/eatexmoor NORTHMOOR GIN JenVisitnette Exmoor EXMOOR’S PREMIUM QUALITY LOCALLY PRODUCED GIN. FOR A LIST OF LOCAL OUTLETS OR TO ORDER ONLINE VISIT: www.exmoordistillery.co.uk UNIT 5, BARLE ENTERPRISE CENTRE, DULVERTON, EXMOOR, SOMERSET, TA22 9BF PHONE: 01398 323 488 Eat Exmoor Guide Eat Exmoor Guide Copywriting: Jennette Baxter (www.Visit-Exmoor.co.uk) Selected Food Photography: Julia Amies-Green (www.Flymonkeys.co.uk) Design & Production: Tim Baigent (www.glyder.org) With Support from Exmoor National Park Authority. Exmoor’s Landscape –A Farmer’s Perspective Exmoor’s unspoilt landscape is of livestock, hence the characteristic a major reason why it became a patchworks of grassy fields bounded national park, but even its ancient by high hedges. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk.